Читать книгу A Husband For Mari - Emma Miller - Страница 8

ОглавлениеChapter One

Wisconsin

Mari rolled up her grandmother Maryann’s red-rooster salt-and-pepper shakers in a stained dish towel and stuffed them into a canvas gym bag. “What time is your boyfriend picking you up?” she asked her soon-to-be-ex roommate.

Darlene pulled her head out of the dark refrigerator, a carton of milk in her hand. There wasn’t anything left but condiments, two eggs and the quart of chocolate milk. With the electricity shut off for the past forty-eight hours, Mari wouldn’t have touched the milk. Darlene took the cap off and sniffed it. “Twenty minutes.” She wrinkled her nose and took a swig. “You want the eggs?”

Mari shook her head. “You take them. I can hardly carry them to Delaware, can I?”

Darlene, thin as a rake handle, features embellished by enough dollar-store makeup for all the participants in a toddlers’ beauty pageant, tucked the egg carton into a cardboard box. “Suit yourself.” She picked up a green rubber band that had once secured celery and gathered her dyed midnight-black tresses into a ponytail. “I’m gonna run next door and use the bathroom before Cassie goes to work.”

Mari nodded; they’d been using their neighbor’s bathroom since the electric was disconnected. Darlene went out the front door, inviting an arctic blast in, and Mari shivered.

She sure hoped it would be warmer in Delaware. Wisconsin winters were brutal. If it wasn’t for the kerosene heater, they couldn’t have stayed there the past two days. She rewrapped the wool scarf she wore and gazed around. There wasn’t anything about the old single-wide trailer with its ratty carpet and water-stained walls that she was going to miss. She had very little to show for eighteen months in Friendly’s Mobile Home Park: few belongings and no real friends. She and Darlene had become housemates only because they worked on the same assembly line at the local plant and were both single mothers. They weren’t really friends, though. They were just too different.

Feeling the need to do something besides stand there and feel sorry for herself, Mari grabbed a broom and began to sweep the kitchen. She couldn’t wash out the refrigerator or wipe down the cabinets, but she could sweep at least. That didn’t take water or money, which was a good thing, because she didn’t have either. She almost laughed out loud at the thought.

Money had been short since the plant closed and her unemployment ran out. Even shorter than it had been before. Jobs were scarce in the county. Mari had picked and sorted apples, cleaned houses and even tried to sell magazines over the phone. She read the want ads every day, but employment for a woman with an eighth-grade education and few skills was nearly impossible to find.

She pushed her hand deep into her pocket to reassure herself that Sara Yoder’s letter was still there and that she hadn’t just dreamed it. Sara, an old acquaintance from her former life, was her only option now. If it hadn’t been for Sara’s encouraging letters and her unsolicited invitation to come stay with her in Delaware, Mari didn’t know where she and Zachary would be sleeping.

Mari swallowed hard. She shouldn’t dwell on how bad things had gotten, but it was hard not to. First her car had died, and then she couldn’t keep up with her cell phone bill. She’d found a few days of work passing out samples of food in a supermarket, but, living in a rural area, without transportation, it was impossible to keep even that pitiful job. Her meager savings went fast; then came the eviction notice.

Mari had tried her best these past few years, but it was time to admit that she was a failure. A bad mistake, poor judgment and a naive view of the world had gone against her. She had nothing but her son now, and she was worried about him. Worried enough to move a thousand miles away.

At nine years old, Zachary was becoming disillusioned with her promises and forced optimism. She was always saying things like “When I find a better job, we’ll rent a place where you can have a dog.” Or “I know it’s a used bike, but maybe next year I’ll be able to buy you the new bike that you really wanted for your birthday.” Secondhand clothes, thirdhand toys and a trailer with a leaky roof were Zachary’s reality. And her bright, eager child was fast becoming moody and temperamental. The boy who’d had so many friends in first and second grade now had to be dragged away from watching old DVD shows on the TV and coaxed to get out of the house to play. In the past month, he’d brought home two detention notices, and most mornings he pretended to have a stomachache or a headache in an attempt to avoid school. She was equally concerned about the envy Zachary had begun to exhibit toward other boys in his class, boys who had name-brand clothing, cell phones and TVs and PlayStations in their bedrooms.

She’d wanted to dismiss Zachary’s unhappiness as just a stage that boys went through. A few bad apples in his classroom, a difficult teacher, an ongoing issue with a school bully, would make anyone depressed. But those were all excuses.

Mari knew she had to do something different. She couldn’t keep relying on neighbors or roommates to keep an eye on Zachary while she worked odd shifts and weekends. She needed a support system, someone who cared enough about them to see that he got off to school if she had to leave early, someone to be there if he was sick or she had to work late.

Mari had thought she could raise him alone, but she was beginning to realize she couldn’t do it. Love wasn’t enough. It was her concern for her son that had given her the courage to agree to move to Delaware. She needed to provide for her child, and she needed to give him what he had never had: structure, community and a real home where he wouldn’t be ashamed to bring his friends.

Seven Poplars, Delaware, the town that Sara Yoder had moved to, had become a refuge in Mari’s mind, the hope of a new beginning. In her dreams, it was a place where she and Zachary could make right what had gone wrong in their lives. Sara had offered her a room in her home and the promise of a job. There would be a tight-knit community to help with Zachary, to watch over him, to teach him right from wrong. And if it meant returning to the life she’d thought she’d left behind forever, that was the sacrifice she would make for her son’s sake.

The groan of brakes one street over told Mari that Zachary’s bus had entered the trailer park. She put away the broom and began to stack the few bags they had on the couch. Sara had hired a van and driver to take them to Delaware.

The door banged open and Zachary came up the steps and into the trailer, head down, his backpack sagging off one shoulder.

“I hope you had a good last day.” She tried to sound as cheerful as she could as she closed the door behind him to keep out the bitter wind. “There’s still a couple of things—” She halted midsentence, staring at him. He wasn’t wearing a coat. “Zachary? Did you leave your good coat on the bus?” Her heart sank. It wasn’t his good coat; it was his only coat. She’d found it at a resale shop, but it was thick and warm and well made. “Where’s your coat?”

He shrugged and looked up at her with that expression that she’d come to know all too well over the past months. “I don’t know.”

Mari suppressed the urge to raise her voice. “Did you leave it on the bus or at school?” She closed her eyes for a moment. There was no time to go back to school to get his coat before the hired van came for them, and she had no way to get there even if there was.

Zachary dropped his old backpack to the floor. He was wearing a hooded sweatshirt, hood up, but he had to be cold. He had to be frozen.

“I’m sorry about the coat,” he muttered, not making eye contact. “But it wasn’t all that great. The zipper kept getting stuck.” He hesitated and then went on, “It wasn’t in my cubby this afternoon. I think one of the guys took it as a joke. I looked for it, but the second bell rang for the buses. I knew I’d be in trouble if I missed my ride home.” He swallowed. “I’m sorry, Mom.”

She took a breath before she spoke. “It’s all right. We’ll figure something out.” She dropped her hands to her hips and glanced down the hall. “You should see if there’s anything left in your room you want to take. Check under the bed. The van will be here for us soon.”

Zachary grimaced. “Mom. I don’t want to go. I told you that. I won’t have any friends there.”

And how many do you have here? she thought, but she didn’t say it out loud. “You’ll make new friends.” She forced a smile. “Sara said the kids in the neighborhood are supernice.”

He wrinkled his freckled nose, looking so much like his father, with his shaggy brown hair and blue eyes, that she had to push that thought away. Zachary was his own person. He wasn’t anything like Ivan, and it was wrong of her to compare them.

“You’re talking about Dunkard kids,” he said.

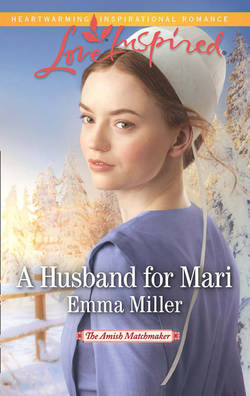

“Not Dunkards. That’s not a nice word. I’m talking about Amish kids. It’s an Amish community. Sara is Amish, and she’s—”

“A weirdo,” Zachary flung back. “I told you I don’t want to go live with her. I don’t even know her. I’ve seen those people in town. They wear dumb clothes and talk funny.”

Mari pulled her son into her arms and held him. He didn’t hug her back, but at least he didn’t push her away. “It’ll be all right,” she murmured, pulling back his hood to smooth his hair. “Trust me. You’re going to like it there.”

“I’ll hate it.” He choked up as he pressed his face against her. “Please don’t make me go. I don’t want to live with those weirdos,” he sobbed.

“Zachary, what you don’t realize,” Mari said, fighting her own tears, “is that we are those weirdos.”

Seven Poplars, Delaware, three days later...

The rhythmic sounds of rain drumming against the windows filtered through Mari’s consciousness as she slowly woke in the strange bed. She sighed and rolled onto her back, eyelids flickering, mind trying to identify where she was. Not the trailer. As hard as she’d worked to keep it clean, the mobile home had never smelled this fresh. Green-apple-scented sheets and a soft feather comforter rubbed against her skin. Mari yawned and then smiled.

She wasn’t in Wisconsin anymore; she was in Delaware.

There was no snow, but there was rain. They were farther south, and the temperature was warmer here. They’d driven through a winter storm to get to Delaware. The van drivers, a retired Mennonite couple, had been forced to stop not for the one planned night, but two nights because of icy conditions and snow-clogged roads. Mari and Zachary had finally arrived, exhausted, sometime after eleven the previous night.

Mari rubbed her eyes and glanced around the bedroom; there were two tall walnut dressers side by side on one ivory-colored wall and simple wooden pegs on either side of the door for hanging clothing. Simple sheer white curtains hung at the windows. It was a peaceful room, as comfortable as the beds. An Amish home, she thought sleepily, as plain and welcoming as her grandmother’s house had always been but her uncle’s never had. And this one had central heat, she realized as she pushed back the covers and found her way to the chair where she’d laid out her clothes the night before.

She could hear Zachary’s steady, rhythmic breathing. She considered waking him, but decided that he needed his sleep more than he needed to be on time for breakfast. Sara had told her that they ate early so that Ellie could be at the schoolhouse on time.

Ten minutes later, face washed and teeth brushed, Mari came down the wide staircase to find Sara in the living room. “Good morning,” Mari said.

“I thought you’d sleep in.” Sara, short and sturdy and middle-aged, smiled. She was tidy in her blue hand-sewn dress, black stockings and shoes, and white apron. Her crinkly dark hair was pinned up into a sensible bun and covered with a starched, white prayer kapp. “But I know the girls will be happy to have you join us for breakfast.”

“Should I wake Zachary?” Mari rested her hand on the golden oak post at the foot of the steps.

“Let the child catch up on his sleep. I’ll put a plate on the back of the stove for him. What he needs most is plenty of rest first, then pancakes and bacon.”

The sound of a saw cutting wood on the other side of the wall startled Mari, and Sara gave a wave of dismissal. “As you can hear, we’re in the midst of adding a new wing onto the house. I apologize for the noise this time of the morning, but the boys like to start early so they can get in a full day’s work and still get to their chores at home after. Hope they won’t wake Zachary.”

“It’s fine,” Mari said. “Once he’s asleep, he sleeps hard. Never hears a thing.”

“Good. When I bought the house, I thought that it would be big enough,” Sara explained, folding her arms across her ample bosom. “But I didn’t realize how many young people would want to stay with their matchmaker. I’ve got a girl living here now, Jerushah, who leaves for her wedding in Virginia in a few days.”

Sara was speaking English, for which Mari was grateful. Deitsch was the Alemannic dialect brought to America by the Amish and used in most households, but she hadn’t spoken Deitsch in years, and Zachary didn’t understand it at all. That was another adjustment he’d have to make if they remained in the community for any length of time, which she hoped wouldn’t be necessary. In light of Zachary’s reluctance to make the move to Delaware, the language difference was something she hadn’t mentioned. Mari suddenly felt overwhelmed.

What had she been thinking when she’d agreed to come to Seven Poplars? A new school, new customs and a different language for her son? How could she expect a nine-year-old, raised in the English world, to adjust to living among the Amish? Even temporarily? Zachary had never lived without modern transportation, electricity, cell phones and television. And he’d never known the restrictions of an Old Order Amish community that largely kept itself separate from Englishers.

But what choice had she had? Apply for state assistance? Take her child into a homeless shelter? She could never blame those mothers who had made that choice, but if it came to that, it would snuff out the last spark of hope inside her. She would know that she was as stupid and worthless as her uncle had accused her of being, the same uncle who had offered to let her come home if she put her baby up for adoption.

Mari mentally shook off her fears. It never did any good to rethink a decision. She would embrace the future, instead of looking backward at her failures. She would make this work, and she would secure a better life for her and her son. “So the job at the butcher shop that you mentioned in your last letter...it’s still available?”

“Sure is.” Sara’s lips tightened into a firm pucker while her eyes sparkled with intelligence and good humor. “Not to worry. I told you that if you came to Delaware, we’d soon straighten out your troubles.”

In spite of her jolly appearance, Mari knew that Sara Yoder was a woman who suffered no nonsense. Fiftyish and several times widowed, shrewd Sara was a force to be reckoned with. Like all Amish, her faith was the cornerstone of her life, but she’d been one of the few who’d not condemned Mari when she’d gotten with child out of wedlock and run from her own Amish community.

“Thank you.” Mari sighed with relief.

“Enough of that. You’ll do me credit. I’m sure of it. Now, come along and have a good breakfast.” Sara bustled toward the kitchen, motioning for Mari to follow. “And don’t worry about the job. I told Gideon that he’d best not hire anyone to run the front of the store until he’d given you a fair shot at it.” She glanced back over her shoulder, her expression clearly revealing how pleased she was herself. “I found the perfect wife for Gideon, and he owes me a favor.”

Sara had written that Gideon was looking for someone to serve customers, take orders and deliveries, and act as an assistant manager of his new butcher shop, where he’d be featuring a variety of homemade sausages and scrapples. Sara had explained that he needed someone fluent in English and able to deal easily with telephones and computers, someone who could interact with both Amish and non-Amish. She hadn’t mentioned what the wages or hours would be, but Sara had assured her that Gideon would be a fair employer. And, most important, someone would always be at Sara’s house to watch over Zachary while she was at work.

The smell of dark-roasted coffee filled the air. Sara’s home was a modern Cape Cod and laid out in the English rather than the Amish style, but in keeping with Plain custom, she had replaced the electric lights with propane and kerosene lamps. As Mari walked through the house, she felt herself being pulled back into her childhood, although the homes she’d grown up in were never as nice as this. Sara’s house was warm and beautiful, with large windows, shining hardwood floors and comfortable furniture. Sara had apologized that Mari and Zachary had to share a room, but it was larger and nicer than anything either of them had ever slept in. Mari only hoped that someday she could find a way to repay the older woman’s kindness.

“There you are!” Ellie declared as they entered the kitchen. “I was hoping to see you before I left for school.” Ellie, the vivacious little person Mari had met the previous night, stepped down from a wooden step stool beside the woodstove and carried two thick mugs to the long table that dominated the room. She couldn’t have been four feet tall. “How do you like your coffee, Mari?”

“With milk, please,” Mari replied, returning Ellie’s smile.

It was impossible to resist Ellie’s enthusiasm. With her neat little figure, pretty face, sparkling bright blue eyes and golden hair, Ellie was so attractive that Mari suspected that had she been of average height she would have been married with a family rather than teaching school.

Already at the kitchen table was shy and spare Jerushah, the bride-to-be whom Sara had spoken of. “Sit down, sit down,” Sara urged. “Ellie has to leave at eight.” Sara gestured toward the silent, clean-shaven Amish man at the end of the table. “This is Hiram. He helps out around the place.”

Hiram, tall, thin and plain as garden dirt, kept his eyes downcast and mumbled something into his plate, appearing to Mari to be painfully shy rather than standoffish.

Ellie pushed a platter of pancakes in her direction. “Don’t mind Hiram. He’s not much for talking.”

“Shall we take a moment to give thanks?” Sara asked.

Mari bowed her head for the silent prayer that preceded all meals in Amish households. That would be another change for Zachary. Oddly, she felt a touch of regret that she hadn’t kept up the custom in her own home.

“Amen,” Sara said, signaling the end of the prayer. And although they were all strangers to her, except for her hostess, Ellie and Sara began and kept up such a good-natured banter that it was impossible for Mari to feel uncomfortable. Again, all the conversation continued in English. Jerushah’s barely audible voice bore a Midwestern lilt with a heavy Deitsch accent, but Ellie and Sara spoke as if English was their first language. Hiram didn’t say anything, but he smiled, nodded and ate steadily.

“You have the buggy hitched?” Sara asked Hiram. “Rain’s let up, but it’s too cold for Ellie to be walking.”

“Ya,” Hiram answered. No beard meant that he wasn’t married, but Mari couldn’t have guessed his age, somewhere between forty and fifty. Hiram’s sandy hair was cut in a longish bowl-cut; his nose was prominent and his chin receding. His ears were large and, at the moment, as rooster-comb red as Sara’s sugar bowl. “Waiting outside when she’s ready,” he said between bites of egg.

Hiram had slipped into Deitsch, and Mari was pleasantly surprised to realize that she’d understood what he’d just said. Maybe she hadn’t forgotten her childhood language.

One bite of the blueberry pancakes and Mari found that she was starving. She polished off a pancake and a slice of bacon, and she was reaching for a hot biscuit when she became aware of the sound of an outer door opening and the rumble of male voices.

“My carpenter crew.” Sara slid a second pancake onto Mari’s plate. “Better put on a second pot of coffee, Ellie.”

Mari suddenly felt self-conscious. She hadn’t expected to meet so many people before eight in the morning her first day in Seven Poplars. Now she was glad that she’d chosen a modest navy blue denim jumper, a black turtleneck sweater and black tights from her suitcase. And instead of her normal ponytail, she’d pinned up her hair and tied a blue-and-white kerchief over it. She wasn’t attempting to look Amish, but she wanted to make a good impression on Sara’s friends and neighbors. Not that she’d ever been one for the immodest dress many English women her age went for; she’d always been a long skirt and T-shirt kind of girl.

Five red-cheeked workmen crowded into the utility room, stomping the mud off their feet; shedding wet coats, hats and gloves; and bringing a blast of the raw weather into the cozy kitchen.

“Hope that coffee’s stronger this morning, Sara,” one teased in Deitsch. “Yesterday’s was a little on the weak side. It was hard to get much work out of Thomas.” The speaker was another clean-shaven man in his late twenties or early thirties.

“That’s James,” Sara explained in English. “He’s the one charging me an outrageous amount for my addition.”

“You want craftsmanship, you have to pay for it,” James answered confidently. He strode into the kitchen in his stocking feet, opened a cupboard door, removed a coffee mug and poured himself a cup from the pot on the stove. “We’re the best, and you wouldn’t be satisfied with anyone else.”

“Nothing wrong with Sara’s coffee,” chimed in a second man, also beardless and speaking English. “James is just used to his sister’s. And we all know that Mattie King’s coffee will dissolve horseshoe nails.” He glanced at Mari with obvious interest as he entered the kitchen. “This must be your new houseguest. Mari, is it?”

“Ya, this is my friend Mari.” Sara introduced her to the men as they made their way into the kitchen and began to pour themselves cups of coffee. “She and her son, Zachary, will be here with me for a while, so I expect you all to make her feel welcome.”

“Pleased to meet you, Mari,” James said. The foreman’s voice was pleasant, his penetrating eyes strikingly memorable. Mari felt a strange ripple of exhilaration as James’s strong face softened into a genuine smile, and he held her gaze for just a fraction of a second longer than was appropriate.

Warmth suffused her throat as Mari offered a stiff nod and a hasty “Good morning,” before turning her attention to her unfinished breakfast. She took a piece of the biscuit and brought it to her mouth, then returned it untasted to her plate. She kept her eyes on her pancake, watching the dab of butter slowly melt as she felt the workmen staring at her, no doubt curious about her presence at Sara’s. Mari didn’t want anyone to get the idea that she’d come to Seven Poplars so Sara could find her a husband. That was the last thing on her mind.

“Thomas would rather drink coffee than pound nails any day,” Ellie teased as he took a seat at the table.

“And who wouldn’t, if they were honest?” Thomas chuckled. “Pay no attention to her, Mari. Any of these fellows can tell you what a hard worker I am.”

“I hope you’re not disappointed we’ve got rain instead of snow this week.” James pulled out a chair across from Mari. He unfolded his lean frame into the seat with the grace of a dancer. He wasn’t as tall as Thomas. His hair was a lighter shade, and his build was slim rather than broad, but he gave an impression of quiet strength as he moved. “I know you had plenty of snow in Wisconsin.”

“I don’t mind the rain,” Mari heard herself say. “And I definitely appreciate the warmer temperature.”

Her comment led to a conversation at the table about the weather, and Mari just sat there listening, wondering why she felt so conspicuous. Everyone was nice; there was no need for her to feel self-conscious.

“Well, I hate to leave good company,” Ellie said, getting to her feet. “But if I’m not at school when Samuel’s boys get there to start the fire, they won’t be able to get in.” She tapped the large iron key that hung on a cord around her neck. “They’ll be wet enough to swim home.” After putting her plate in the sink, she picked up a black lunch box and a thermos off the counter. “Are you ready, Hiram?”

Hiram wiped the last bit of egg from his plate with a portion of biscuit and stuck it into his mouth. “Ready.”

Ellie smiled at Mari. “See you after school?”

“Of course. Unless...” Mari glanced back at Sara. “Unless I’m supposed to go to work today.”

“Ne,” Sara assured her. “Not today. Gideon and Addy have just thrown open their doors, so the pace is still slow. Gideon said tomorrow would be fine. Give you a chance to settle in.”

“Going to be working for Gideon and Addy, are you?” James remarked as he added milk to his coffee from a small pitcher on the table.

Mari slowly lifted her gaze. James had nice hands, very clean, his fingers well formed. She raised her gaze higher to find that he was still watching her intently, but it wasn’t a predatory gaze. James seemed genuinely friendly rather than coming on to her, as if he was interested in what she had to say. “I hope so.” She suddenly felt shy, and she had no idea why. “I don’t know a thing about butcher shops.”

“You’ll pick it up quick.” James took a sip of his coffee. “And Gideon is a great guy. He’ll make it fun. Don’t you think so, Sara?”

Sara looked from James to Mari and then back at James. “I agree.” She smiled and took a sip of her coffee. “I think Mari’s a fine candidate for all sorts of things.”