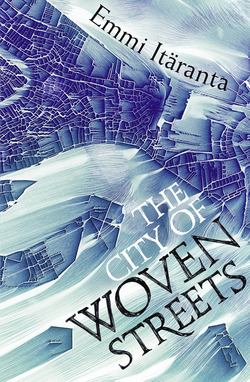

Читать книгу The City of Woven Streets - Emmi Itaranta - Страница 9

CHAPTER FOUR

ОглавлениеA gondola arrives for Mirea at dawn. We all hear the squeaking of the metal cables as the vessel approaches, hovers above the drop and climbs slowly to the port on top of the hill. I am not outside to see it, but the walls of the Halls of Weaving make every sound swell in my ears: the heavy footsteps, rarely heard in the house; the indistinct words of Weaver’s voice; and, eventually, Mirea’s weeping. I imagine two silent and dark figures taking her into the black gondola bearing the emblems of the City Guard, which will return down to the city across the void. Once its bottom touches water, the large hooks holding it to the airway will be detached. The vessel will float down the canal, turn to a waterway running towards the House of the Tainted and finally stop before the locked iron gate. I imagine Mirea: struggling and fighting, her body wriggling like a slippery fish at the bottom of the boat. Or quiet, submissive, her face closed.

None of us flinches, or slows down the work, or stops it.

Later, when the weather turns warmer, the folding doors of the Halls of Weaving are opened towards the square. Many weavers carry their looms outside, under the canopy woven of web-yarn. If interior and exterior spaces can be separated from each other in the House of Webs, that is: here, rooms move often. The dormitories and cells remain. They are built in stone, because sleep must be confined within solid walls, it cannot be released to wander free. But around the stone buildings the rooms, walls and streets wax and vanish, nor are they supposed to stay. That is the will of Our Lady of Weaving.

Days are seldom warm this late in autumn. The sun draws soft shadows on the walls and casts them across the floors, falls through the half-woven wall-webs. Clouds break the edge of the light. The long rows of weavers reach from the room all the way to the square. Their hands pass the weft through the warps, building within the frames fabrics that are all alike. No exceptions are allowed. The only sounds in the hall are the rustling of clothes, the swishing of yarn and the breathing of dozens of women. The coarse sea-wool stings my fingers until their skin cracks, and my weave is not as smooth as I would like.

I pat the weft with a wooden weaving fork to make it a tighter fit with the rest of the web. The warp rises tall and bare ahead of me. On my left side Silvi, who came to the house three years after me, has already woven twice as much as I this morning. My weft twists into a tangle and leaves a large, protruding loop in the wall-web. I am so focused on tugging the knot free that it takes me a while to notice the low chatter that has grown in the hall, and the stopped movements. Silvi stares away from the square and folding doors, towards the arched stone doorway between the hall and the corridor.

The girl tattooed with invisible ink stands at the door of the hall. She has changed her white patient gown for a long, grey wool dress and tied her hair low in the nape of her neck. The skin around her mouth still looks slightly swollen and bruised, but she stands straight and without hesitation. Her gaze circles the hall and stops on me.

I place the shuttle down. The girl begins to walk towards me. I catch uncertain looks and tense postures from the corner of my eye. Outsiders are not allowed in the Halls of Weaving. Yet no one rises to stop her; neither do I. Outside clouds part, and the sky casts sudden light across the hall. A shining forest of halfway webs reaches in all directions. She walks to me, tilts her head and the corners of her mouth lift, just a little. I do not know what moves on my face, but something must do. She sits down on the narrow seat next to me, so close I smell the soap on her skin. For a few moments, neither of us moves. I breathe her in.

She places a hand on top of the shuttle resting in my lap. Her fingers brush it briefly before settling on the polished wooden surface. Its shape is a familiar fit against her touch. She looks at me, face close to mine, and tilts her head again. Her expression poses a question.

It is quiet enough to hear a hundred simultaneous breaths drawn in the hall. Only those chosen as apprentices are allowed to weave in the house. Anything else is forbidden. Everyone stares at us.

I nod.

The girl nods back. I feel her breath brush my neck. She picks up the shuttle and begins to pass it through the warp. Her movements are swift and sure. The yarn slides without clumping, and I see immediately that the resulting weave will be smooth and dense. When the wall-web is ready in its frame, it will show the place where the shuttle passed from my hands to hers: the lumpy, sometimes too tight and occasionally too loose texture turns even and made with skill.

I remain seated, although the seat is too narrow for both of us, and she is tightly pressed against me. There are footsteps at the door. Alva steps into the hall, her face red and her breathing heavy.

‘I’m sorry,’ she says. ‘She disappeared while I was outside drawing water from the well. I will take her back immediately.’

I look at the girl’s hands again, the endlessly intertwining strands sliding through her fingers.

‘I don’t think she wants to go back,’ I say.

The gondola from the Hospital Quarters arrives that evening and takes away six rash-covered, violently coughing weavers. The girl is not among them. On the second day after I have handed my shuttle to the girl, she steps into the halls with Weaver. Together they set up a new loom in the corner and stretch the warp between the upper and lower beams. The girl carries a seat in front of the frame and sits down, places the shuttle, a skein of yarn and a weaving fork next to her, and begins to work. Weaver keeps an eye on the girl for a while, and when she leaves, no one says anything. We all take secret glances at the girl. Once she glances back at me. I can only see her face diagonally from the back, but the cheek turned towards me lifts as if she is smiling.

After supper I sit in my cell, detach the coin pouch from my waist and pour the coins in front of me on the bed. The House of Webs pays a small monthly salary and clothes its residents, because the servants of Our Lady of Weaving are expected to look tidy. But my socks have worn thin, and there will not be new ones on offer until spring. I begin to count the coins to see if I can afford to buy a pair of warm socks at the market for winter. My fingers brush something oblong. For a moment I am confused, but then I remember the metal object the dark-clad woman dropped at my feet on the day of the Ink-marking. I pick it up. It is a small key. I turn it in my fingers. Its teeth are simple, but one end is unusually shaped: it is tapering, like an eye, and in place of a pupil an eight-pointed sun shines at the centre, the emblem of the island and the Council.

There is a knock on the door. I drop the key back into the coin pouch, collect the coins from the bed in a hurry and tighten the mouth of the pouch. I get up to open the door. Weaver stands behind it with the girl who is carrying a pile of clean bed linen in her arms.

‘Eliana,’ Weaver says and places her hand on the girl’s shoulder. ‘She will stay in the house for the time being. At least until we find out where her home is.’

I glance at the bed linen and understand.

‘Can we come in?’ Weaver says. ‘I have no doubt she would like to prepare her bed.’

‘Can’t she live in the sick bay?’ I ask, and my voice sounds harsher than I had intended. The girl shifts her weight from one foot to the other. ‘Or in one of the dormitories?’

‘The sick bay has five new cases of rash, and we do not want more infections. After what she has been through, I trust you understand that she would prefer more privacy than a dormitory can offer.’

‘I cannot sleep when there is someone else in the room,’ I try.

Weaver looks at me from her heights, eyes black in the dark face.

‘I thought you did not sleep anyway,’ she says. ‘She is your roommate for the time being. I will leave you to make closer acquaintance.’

I know the conversation is over. I move to the side and let the girl in. She places the bed linen on the night table next to the empty bed. The table is too small, and the sheets fall to the floor. She picks them up with hasty hands and begins to make the bed without looking at me. Weaver simply nods and leaves.

I do not know where to look. There is little to do in the cell in the evenings after work. My former roommate usually wanted to chat about seamen and jewellery sold in the market, or how many children each of us would have when we found husbands and left the house. I mostly responded with a few syllables, if at all. That never seemed to bother her.

The girl gets the linen in place and begins to take off her dress, which seems slightly too big for her. I look away and hear her slip under the blanket in her thin undergarment.

‘It would be good for you to know that I sleep less than most others,’ I say. ‘I’m often on night-watch.’ It seems like a sufficient explanation.

Her eyes are wide in the dusk, their colour metal-sharp.

‘I didn’t mean to be rude,’ I say. ‘I’m sorry. I just haven’t shared a room with anyone for a long time.’

I close the curtains. The glow-glass globe on the night table dims slowly. I take off my jacket, change into my nightgown and lower myself to bed. I turn towards the wall.

I hear the sheets rustling and the bunk creaking under the girl. Apparently she too has turned her back on me. It feels as if I can sense the warmth of her body across the room. I close my eyes and fear falling asleep. From her breathing I can tell she is not sleeping, either.

As weeks pass, the girl and I try to get used to each other’s presence in the small space that is now new to both of us: to her because she does not yet know it, and to me because the strange, shifting element of her limbs and hair and shape has been added to my former privacy. I begin to understand I am also responsible for introducing her to the ways of the house. She follows me into the washrooms in the morning and to the supper table, although she cannot eat normally yet. She bends her head down to the floor of the Halls of Weaving after me and goes to sleep when I do. I stay awake and watch her, but some nights exhaustion eventually drops me to sleep. When images begin to form behind my closed lids, she seems to chase them, too. The walls of sleep fall quiet into deep water, and she climbs on them before me. I follow her through low and tall doors to dream-rooms where branch-stiff lattices cover the windows. I seek her in dream-halls where black water rushes in the rifts of cracked floors and walls are fraying webs, because the threads run from their meshes and everything unravels. I want the floors to be unbroken and they close their cracks in front of my footsteps. I want the walls to be whole again and the yarn interweaves back into meshes, but it escapes my grasp and I cannot reach it, and each new wanting is without strength.

When I wake with a start in the light of night or dawn, I hear the girl’s breathing on the other side of the cell.

I should perhaps know how to read these signs:

That morning, when I arrive at the Halls of Weaving with the girl at my heels, I see two City Guards enter Weaver’s study.

My shadow has moved two palm-widths on the wall, when a weaver who is on messenger duty steps into the hall, bows her forehead to the floor, walks to the girl and says something to her in a low voice. They leave the hall together.

The air gondola cables screech under the weight of a vessel.

At lunch I keep a vacant seat next to mine, but she does not come.

No one touches her wall-web for the rest of the day.

I am on my way to the cell after supper, when Weaver stops me in the corridor.

‘Come to my study,’ she says. ‘I must tell you something.’

The tapestries on the walls are dark and their patterns seem to move while you look away. I sit on the chair Weaver has offered me. This is not the Scolding Chair, but one of the better ones, with a high back and a smoother shape.

‘Two City Guards came to the house today,’ Weaver says. ‘They were trying to track down someone who missed her Ink-marking recently.’

For some reason I think of the key, of the woman on the square. Of the guard who saw me. On the wall Our Lady of Weaving raises all her hands, inviting the sea to storm.

‘I did not miss my visit,’ I say.

‘I know,’ Weaver replies. ‘But someone named Valeria Petros did.’

She pauses and watches me. I search my memory for the name and do not find it.

‘Who’s that?’ I ask.

‘Your roommate,’ Weaver says. ‘She confirmed it today when the City Guard spoke to her.’

I reach for the girl’s thoughts, try to imagine what I would have done. She must have been too badly injured and heavily medicated to even know what day it was. She could have gone later, but how would she have explained what had happened without words? And whoever attacked her probably still walks the streets of the city, eyes perhaps ready to see, hands ready to capture and kill this time.

‘Will Valeria Petros leave the house now?’ I ask. The thought hits me deeper than I expect.

‘She will stay,’ Weaver says.

‘Doesn’t she want to return to her family?’

‘I am certain she would like to,’ Weaver says. ‘Unfortunately it is not possible.’ She pauses. ‘You will remember that air gondola accident the night she arrived.’

I nod.

‘Her parents were in the gondola that crashed. There were no survivors.’

A cold weight settles into my chest. I think of the cables in the sky, of their distance from the ground below, or water. When you fall from that high, it matters little what is underneath. An image from the week before arises in my mind: Valeria’s darkening face when Alva mentioned the air route crash. She must have known her parents were travelling by gondola the night she was attacked. She must have wondered.

‘Doesn’t she have anyone else?’ My voice is evened by years of practice, as if it belongs to another.

‘She has an aunt, an inkmaster. I have sent her a message. But Valeria has indicated she prefers to stay here. And I do believe her skill is put to better use within these walls.’

I recall the night Valeria arrived at the house. I see the pain curled on her face, the bloodstains on the stones of the square.

‘Do you know who attacked her?’

Weaver shakes her head.

‘I’m afraid the City Guard do not seem to have made progress on that front.’

She is quiet. The tapestries move, are still and move again. A cold draught travels across the room. I glance at the corner. The door is closed behind the glass frame of the watergraph. Weaver has pushed the hood back from her face. She does not do that often. Her face is dark and nearly smooth, although it cannot be young. Her short hair curls close to the curve of her head.

Weaver breaks the silence.

‘There is one more thing.’

I wait.

‘Valeria’s parents have already been cremated. She didn’t want a place for them in the burial ground. But as their daughter she must collect the ashes from the House of Fire. She will need someone to accompany her.’

‘I will do it,’ I say.

‘Yes, you will,’ Weaver says. ‘You may go now.’ She turns to the pile of papers on the table and picks up a pen. It begins to rustle on paper.

I walk to the door where I stop, because an unexpected thought takes shape in my mind. No one should have to travel beyond the Web of Worlds without thoughts and deeds to smooth the way. I cannot do much for the girl, but this I can.

‘What were their names?’

The rustling stops. Weaver looks up from the papers. The pen hangs mid-air in her fingers, ready to be raised, ready to fall.

‘Valeria’s parents,’ I specify. ‘What were they called?’

‘Mihaela and Jovanni Petros,’ she says.

‘Thank you,’ I say and leave.

I knock on the door of the cell. No response. Quietly I open it. The curtains are closed, and the girl – Valeria, I fit her name in my mouth – has thrown a shawl over the glow-glass on her night table. She is curled under the blanket, a lump of darkness, like grief sealed in a throat. I listen to her breathing and am almost certain she is awake. But I do not say anything, in case I am wrong.

My bed makes a soft creak when I sit down on the edge, even though I try to do it slowly, without sound. Valeria does not move.

My hand wants to reach out to her, stroke the curve of the shoulder and her side, very softly, because words are too heavy right now. Instead I get undressed in the dark as quietly as I can and go to bed. I think of the broken cable, its end swaying in the wind, or perhaps cradled by water, and everything she will never tell her parents. Of how her hours have suddenly turned briefer and her days more brittle, because there is no longer anything between them and emptiness, and she is the next in line.

Valeria stays in the cell for days. I do not see her cry, but when I return from work in the evenings, her eyes are red and swollen. Sometimes she merely lies facing the wall. I bring her soup and bread, the hard crust of which I have scratched off. Sometimes she eats. Mostly she does not.

A week later I climb up a tangled path to a hill where cables do not squeak or webs divert walkers from the way. Low wind-whipped bushes grow here and there among the stones, and stunted trees sticking from the thin soil like gnawed bones. Their yellowing leaves are dappled by bruise-like spots I do not remember seeing the year before. The day is bright, the wings of the white gulls sharp against the sky, but their cries are drowned by the distance. The hill is veiled in silence.

Far at sea I discern earth-coloured ships that do not bear the flags of trading vessels on their masts. Everyone on the island has seen them, but no one knows what they are for. They sail to a secluded harbour near the House of the Tainted, and people do not go there. Some say they have seen pale figures in the port who vanish from sight when they are spoken to. I turn my gaze away from the ships. This day does not need more ghosts.

Janos stands before the arching stone gate at the end of the path, waiting for me. We meet here on the last day of the week after every new moon. He clasps me into a wide hug. The gesture seems out of place, too loud and large, but I do not push him away.

Janos lets me go and looks at me.

‘You have been missing sleep again, sister,’ he says.

‘So have you, brother,’ I respond.

‘Must run in the family,’ he says. His smile is our mother’s.

We both glance around. There are no others on the hill. Or if there are, they will be inside the Glass Grove. From there, they cannot hear us speak.

‘I hear someone was taken from the House of Webs the other week.’

So he has heard. I should have expected it. News always finds its way to the House of Words. I wonder if they have already received word of a strange girl who collapsed on the stones and nowadays sleeps only a cell-width away from me.

‘She was one of the youngest,’ I say. ‘She didn’t have the privacy of the cell to protect her.’

Janos pushes his hands into the pockets of his blue scribe’s cloak. His eyes look to the sky, then at me again. I see serious concern in them.

‘Someone was also taken from the House of Words recently,’ he says.

I do not remember Janos telling me about any Dreamers being discovered in the House of Words in years. Memories come without looking: our mother’s night-maere-black eyes and her moan in a candle-lit room, our father’s hand dropping to her forehead and stroking the evil spirit away. Torn breath in my throat and my mother’s cool fingers on my face, her soothing voice, as I sought the shadow I had seen in the room mere moments earlier. Janos’s face, a dark patch in the light of faint flames. My mother’s words in the dusk: never tell anyone.

‘No one knows,’ I say.

‘I do,’ Janos replies.

‘You would never tell.’

Janos’s smile is our mother’s, but his way of frowning is our father’s.

‘A speculation: one day I’m careless, spill ink over an important codex and spoil it,’ he says. ‘Or make a disrespectful mistake during the next Word-incineration, before the eyes of the whole island. Scribe gets angry with me and throws me out of the House of Words. The City Guard nabs me and tortures me for information.’

‘You are never careless,’ I say. ‘And they don’t do that.’ Except to Dreamers, perhaps, I nearly add. But the truth is I do not know what the guards do in dusky rooms, behind closed walls. Nor what kind of orders the Council do or do not give them from the Tower, from the shelter of their masks.

‘I could compose an essay on the probability of the event, if you want,’ Janos says, raising an eyebrow.

‘No doubt.’ I shove him lightly. He rarely talks of his work, but I imagine the House of Words to be like the House of Webs: rows of scribes in the large Halls of Scribing bent over their desks, dozens of pens rustling on paper and filling the library of the house with copies of old codices, trading contracts, nautical charts, essays on learned subjects.

Our footsteps settle into a shared rhythm, and no one else carries the same childhood memories as the two of us. It makes the world a little less alien to us, and we both know it.

We walk through the gate side by side. The exterior of the arch is worn smooth by winds and rainfalls, but on the inside you can still discern faint traces of figures once carved on the gate. Their shape is not human, but older, stranger. I see more than two limbs, and something that might be a network of threads, or only toothmarks of weather and time in lichen-covered stone. Beyond the gate a path paved with flat, grey slabs crosses an open field of grass, and then, through a narrow opening, leads into the Glass Grove.

Here, light has an underwater quality, like sun sifting through the sea. It glimmers and dapples gold-green along the smooth arches of the glass walls, catches on the metal plates we pass and creates pillars of rays where dust speckles float without weight. This is how I imagine it would be to lie at the bottom of the sea, looking up at the surface and seeing the world above, but different, its shapes unfamiliar, softer, melting into each other, free from the forms assigned for them. Perhaps that is what those who built this place had in mind. Perhaps the rusty hooks in the ceiling above had fish hanging from them once upon a time, smooth and slippery and colourful, or singing medusas. The glassmasters still know how to make their tails swish without movement, how to capture the shape of swimming-bells mid-billow. But if they ever were here, they would have been stolen away long ago. Why leave something beautiful in a place where almost no one comes any more?

We stop before a plate with a waxing moon above waves engraved on it. For generations, only seafarers and fishermen came from our family. Janos and I are the first to be accepted into Houses of Crafts. I sweep aside a vine covering a small shelf under the metal plate. A leaf covered in bruised stains comes loose and floats onto the ground. Nothing is left of the heel of bread we brought last time. All the surrounding shelves are empty, but further away I see a cluster of wasps crawling over a rotting piece of fruit. Someone else still visits, then.

Janos pulls a simple earthenware cup from his pocket and detaches a wineskin from his belt, then pours a little bit of wine into the cup. He places the cup on the shelf, and we bow our heads to speak a quiet greeting to our parents. I think of my mother’s arms, slender and fragile as winter branches, and eventually as grey. I can no longer remember her voice. Every time I visit, yet another piece of her has fallen away, and what remains is so deeply entwined with my own being that I can no longer tell them apart. I think of my father’s eyes, losing their colour under the folds of his lids, fading away like the rest of him. The slow-growing disease they called it, first the neighbours and then the healers, when our parents finally sought them, each in turn. My mother was already gone when Janos was accepted to the House of Words; he was only ten. I was twelve, and had been rejected three times by the House of Weaving. I did not see my father again after they took me in two years later.

Goodbyes were said many times but always buried under other words, and in the end, they were never said at all. Thus we come here again and again, farewells weighing our steps. They are forever late and out of place: a moment gone by we did not recognize when it was within reach, and the ghost of which we will therefore never cease to carry.

But this is what the Glass Grove is for. No remains are kept here. Once the ashes leave the House of Fire, they are scattered into the sea. There is also another burial ground on the island, the place where most people go now. I have heard that there the dead are kept in dark glass coffins, and their features are clearly visible through the lids. The bodies are prepared in such a way that they look like a still image of life even decades later. Their families go to see them and talk to them, and in response they get a mute stare that looks unchanged yet entirely different.

I do not intend to go there. My ashes can be claimed by the sea, and if anyone remembers me once I have left the world, they can come here and whisper their farewells to the sky and trees and vines treading the glass walls.

‘I would like to go to the forest for a moment,’ I tell Janos.

He shrugs.

‘I’ll wait,’ he says. ‘If you don’t mind.’

‘Not at all.’ I had been counting on it.

He makes a space for himself on the stone floor, leaning his back against the wall. I see him close his eyes from the watered-down sunlight coming through the ceiling.

The curve of the inner wall is steeper than the outer, its glass opaque and thick and murky. My mother once told me it was the oldest part of the Glass Grove, perhaps of the city. The treetops rise above it from the encircled forest inside, the only one on the island. The rusty iron gate croaks when I slip through the gap.

The stalks of the bright broadleaves and dark-drizzling conifers push towards the sky smooth and straight, and all is covered by a roof of intertwining branches. Ancient webs of stone are petrified between the trees. There is a tale in the city, one that all weavers know: it tells of the first people of the island, those who were already old before humans came. They taught our kind how to weave, and these webs are all that is left of them. I have walked here many times, touching them and memorizing their shapes. But of course I can never try to replicate them. There is only one way to weave wall-webs, and the patterns, knots and twists of these tapestries of stone are as strange as the creatures that weather has worn away from the gate of the Glass Grove: placed there to be remembered, yet now all but forgotten.

I dig out a piece of bread from my pocket, something I slipped in there at breakfast this morning. The newly dead need nourishment to make their trip to Our Lady of Weaving beyond the Web of Worlds. Valeria can weave, so a web of stone is as good a family crest as any other I can offer. I place the bread under it and kneel. With closed eyes I speak the names of Valeria’s parents and wish them a safe journey, say the words that Valeria can never speak again.

A wind does not rise. A rain does not come. The dead stay dead, and do not respond.

When I get to my feet, sunlight scutters along the stone surface of the webs, and for a moment the air seems to burst in flames, ready to scorch the world and make it anew.

I breathe in. Clouds close the sun away again, and the ancient webs rest shadow-coloured like things that must remain unspoken. I follow my own steps back across snapping twigs and leaves turning into earth.

On the way to the city I tell Janos about Valeria. He listens, then speaks.

‘An invisible tattoo?’

‘Do you know something about them?’

He takes his time to think before saying, ‘Maybe.’

‘You have access to the census records, don’t you?’ I know they are kept in the House of Words.

Janos looks doubtful.

‘The City Guard imagines I have something to do with Valeria because of the tattoo,’ I continue. ‘If you could find anything at all about her family …’

‘It shouldn’t be too difficult,’ he says. ‘But no promises.’

‘No promises.’

We part near the edge of the web-maze, and he continues along Halfway Canal towards a closely-guarded gate that can only be accessed from water. The House of Words does not wish to offer a too-steady foothold to visitors. The low-burning evening sun catches on the webs as I climb up the hill through the paths that only the weavers know.

The door of my cell opens into an empty room. Both beds are neatly made, and the only thing revealing that there are two of us living here now is a half-made ribbon on a weaving tablet, neatly folded on the other bed. I run my finger along the ribbon. Its texture is like in Valeria’s larger work: smooth, dense, skilfully shaped. Without openings you could see through. Behind the window, beyond the forest of webs, the soft lights of the city are slowly flickering to life. I shake the glow-glass awake and take the opportunity to examine my skin all over. It has turned more difficult since Valeria moved into the cell, because I am rarely alone. All I can find are the familiar birthmarks and callouses. I shiver as I get dressed; the room feels crammed and cold. I take to walking along the corridors of the house.

I like the Halls of Weaving best when there are no others there. The rooms that can get crowded, stuffy and sometimes noisy in the working hours feel spacious, fresh and silent. The unfinished works in their wooden frames sleep undisturbed. The Tapestry Room at the far end of the building is my favourite. No tapestries are woven in the house any more; Weaver chooses a few every year to be auctioned off, and their value sustains the house for another year. The old tapestries are made of silk yarn, now impossible to spin, because silkweed died from the seas centuries ago. Their colours are still unfaded, and when I wish to be alone, I often walk among their green trees and flame-coloured flowers and ice-blue waters. The red-dye of blood coral glows brightest of all in them.

On my way I pass the hall where my seat is, and something makes me stop.

There is movement in the darkness of the hall.

Most glow-glasses have gone to sleep and the foldable doors are closed. I wait for my eyes to adjust to the half-dark. Yet I am sure already before I see her clearly, because I recognize the spot in the space of the room. I am always aware of it, the zone she occupies while working. Her hands move ceaselessly, anticipating the exact density of the yarn and unravelling the knots even before they are formed. She sees with her fingers. I can only see her backside, but it would not surprise me if her eyes were closed.

I take soundless steps towards her. She is so focused on her work that she does not notice my presence. I stop behind her, a short distance away.

‘Valeria,’ I say.

She gives a start and turns around. Her face is wrapped in shadows, but I see tears drying on her cheeks. I feel like an intruder and turn my eyes away, look at her work instead. I only realize now that it looks different from the usual wall-webs. There is a pattern forming, the start of something complex and new, although it is too early to tell what shape it is going to take.

‘What are you weaving?’ I ask.

Valeria frowns. Her face tenses. She whimpers, and her eyes well up again. From pain or grief or both, I do not know.

‘You don’t need to tell me,’ I say.

I see her thinking about how to explain this without words. The empty space of silence grows around her like a shadow. When I imagine the agony every sound must create, I feel it as a disease-like prickling at the root of my own tongue. I wish to wind my voice into a skein and hand it to her, even if only for a brief moment, so she could shape from it the words she needs and tell me what there is to be told.

Valeria places the shuttle in her lap and rolls up her left sleeve, revealing the lines of the annual tattoos on her arm. She presses her palms together, lifts them to her cheek and tilts her head against the back of her hand like onto a pillow. She closes her eyes. She breathes deeply with her eyes closed.

‘Something … to do with night-rest and sleep?’ I ask.

Valeria opens her eyes and nods. She runs her finger along the annual tattoos and taps one of them in imitation of the movement of the tattoo needle. She forms a pillow with her hands again and pretends to sleep.

‘And tattoos?’ I say.

The sound of footsteps carries from the outside, but they do not approach. The water of the algae-pool splashes and its surface shatters. Someone is filling a glow-glass. Valeria nods and repeats the series of movements. Tattoos, night-rest.

‘The tattoos … help you sleep better?’ I try. It does not sound sensible, but it is all I have to offer.

Valeria frowns, moves the shuttle next to her on the seat and gets up. She traces the surface of the web with her fingers. I understand she is drawing the invisible pattern that is not there yet. Her hands trace several long lines that run from the centre of the rectangular web radially towards the corners and edges. She draws a circle at the centre of the web, tapping at it emphatically several times. Finally she shapes an outline around everything that resembles a fish, or perhaps an eye.

I stare at the pattern in the air, in my own imagination. In her mind, where I cannot see.

‘I’m sorry,’ I say.

Valeria stares at me through the half-dark.

‘I do want to understand,’ I say.

Valeria’s shoulders fall a little. I see her eyes tear up again. I see her fight it, and lose. She begins to cry, quietly, without loud sobs. I place my hand on her arm. The warmth of her skin hidden by the fabric flows into my fingers and deeper, settles into a glow inside me. I almost pull her into an embrace, but I know nothing about her, and I have no words that will help. We stand there, keeping a distance that does not seem quite short enough or quite long enough.

‘I will try again,’ I say eventually. ‘And again, and again. Until I understand.’

Valeria offers me her hand. I shake it. It feels strangely formal, and yet binding at the same time, something I cannot turn back from. She holds my hand for longer than I expect. When she lets go, I do not have many words left.

‘Are you staying here?’ I manage to ask. ‘You should get some sleep.’

Valeria sits down and picks up the shuttle.

‘I won’t tell anyone,’ I promise. The words leave my mouth the same moment I understand there is no need for them. Weaving outside the working hours is not forbidden. It is just that no one ever does it. It would be considered unusual, but not punishable.