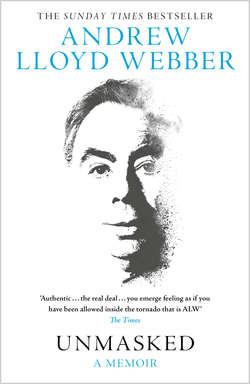

Читать книгу Unmasked - Эндрю Ллойд Уэббер - Страница 18

Оглавление11 Love Changes Everything, But . . .

I first met Sarah Hugill at a birthday party thrown by my friend Sally in Christ Church, Oxford, organized for Lottie Gray. I can still remember the date. January 21, 1970. Sarah was just a slip of a 16-year-old schoolgirl but it isn’t hard to explain why her parents had allowed her out for this bash. They had a little something in common with Sally and Lottie’s families.

Sarah’s father Tony had individually won the Croix de Guerre for bluffing a German commander into surrendering an entire French village. He had served in the 30 Assault Unit set up by James Bond author Ian Fleming. Tony wasn’t over-keen on Fleming. He told me that he spent too much time in Whitehall and not with his men on the front line. Worse, when Fleming did get there, he had a habit of polishing off all their best brandy and cigarettes. Nonetheless Tony gets a big name check in Casino Royale and is supposed to be one of the role models for James Bond himself. Tony’s day job was research chemist to the sugar company Tate & Lyle with special responsibilities for the plantations in Jamaica. But when he was appointed head of the FAO (the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organisation) one of his best friends told me never to take things at face value, although neither Sarah nor I know to this day exactly what this meant. Hence the connection with the parents of the party hostess.

I of course knew none of this when his deliciously open-faced daughter offered to be my secretary. Falling in love with Sarah didn’t take long. I asked her to dinner at the bistro opposite the Michelin building in what London real estate agents poncily now call Brompton Cross. I thought she was ordering ludicrously small, simple things. She didn’t know whether she was supposed to pay her share of the bill. That did it. I had to see her again.

By the end of January I had all the main melodies for our “opera” and Tim’s lyrics were flowing as fast and furious as I was falling for Sarah. My new flat came in very handy. It was only a few hundred yards from Sarah’s school. Since she was supposed to be revising for her summer exams she had loads of free time. So most days she would clock into school and promptly ankle round to me. Fairly soon I gave her a spare key. There are worse things when you’re 21 than a pretty schoolgirl waking you up in the morning. Come March it was time to meet her parents. Thanks to the manners Auntie Vi drilled into me I got on well with my elders and Tony and Fanny Hugill were no exception.

I had dinner at their flat near Kensington High Street. My love of architecture soon had small talk regarding their country home veering towards local churches, thus deflecting possible discussion about the length of my hair. I was invited for a weekend and made a note to wise up on north Wiltshire where their out-of-town pad was located. Over the years I have found that when meeting prospective in-laws it goes down well if you know more about where they live than they do.

LOVE MAY WELL CHANGE everything but in my case it had me writing fast and even more furiously. By mid-February Superstar’s structure was advanced enough for me to break the score down into record sides. My sketches for Side 1 are dated February 21 and the final fourth side dated March 4. Unusual, irregular time signatures are a vital part of Superstar’s construction. They give a propulsive energy to the music and thus to the lyric and the storytelling. There is a December ’69 note that Mary Magdalene’s first song must be in 5/4 time and two months later a big exclamation mark above the 5/4 time signature when it had become “Everything’s Alright.” There’s a double exclamation mark above the 7/4 time signature of the Temple Scene in my notes for Side 2. The biggest note is a reminder to myself about writing a musical radio play with “clarity” scrawled across it and endless reminders about light and shade.

The writing may have sprinted apace but finding our singers was less plain sailing. With a guaranteed record release in the bag, Murray came on board quickly so the key role of Judas was cast. We were anxious to snare a known name as Jesus and Tim pursued Colin Blunstone, the lead singer of the Zombies, whose big hit was “She’s Not There,” written by fellow Zombie, Rod Argent, a fine musician with whom I was to work many times almost a decade later. I had a niggling feeling that Colin’s voice was not rocky enough but the Zombies’ record label CBS shot my worries in the foot by refusing permission for him to record for us point blank.

Help arrived unexpectedly. I had been invited a few months before to the Royal Albert Hall premiere of Jon Lord’s Concerto for Group and Orchestra which featured Lord’s band Deep Purple and the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by a friend of my father’s, fellow composer and lover of cocktails, Malcolm Arnold. There I met Deep Purple’s manager Tony Edwards, a smart businessman who like Sefton also dabbled in show business. I found the music bland, so I droned on about how daring it was to fuse a rock group with an orchestra, I discovered that Deep Purple were contemplating a wise career move and about to go heavy metal. I mentioned something about Superstar and Tony Edwards was intrigued.

Now, several months later, we got a call saying Deep Purple had a new lead singer and would Tim and I like to come round to Tony’s very smart Thames-side house in Barnes and hear some of his rough tapes? His name was Ian Gillan. The moment I first heard the famous Ian Gillan primal scream was the moment I found my Jesus who would now be red blooded and full of spunk, not some bloke in a white robe clasping a baby lamb. That night I went back to my flat and rewrote the moment Jesus slings the moneylenders out of the temple.

Work on Superstar took a temporary back seat and not only because of Sarah. Out of the blue I got an offer to write a film score. The film was called Gumshoe and was directed by a first-timer, the future twice Oscar contender Stephen Frears and starred Albert Finney. Albie, as everyone called him, had set up a small independent film company with the actor Michael Medwin called Memorial Enterprises. Michael, an urbane pin-striped suited chap who frequently played the role of upper-class spiv in British B-movies, had been impressed by the mini buzz around the “Superstar” single and apparently had heard me jaw on about film musicals on some radio programme. The plot of Gumshoe involved Albie as a small time Liverpool bingo caller who fantasizes about being a glamorous Bogey-style private dick. Stephen, who unlike the suave Michael Medwin seemed a man ill at ease with the new Conservative government, wanted a score in Max Steiner style which would be a sort of homage to Bogart and Bacall and coupled with very British working-class locations would raise a wry smile. He also wanted a touch of rock’n’roll. I agreed I was their man. At worst this would be a laugh.

A large contraption called a Moviola was manhandled down my basement stairs. This dinosaur was the then standard editing kit for movies and became extinct almost exactly the time Gumshoe was made. You literally marked up the film where you wanted to cut it. Rather like analogue tape, it has recently made a slight comeback. Stephen would get the operator to run a sequence whilst I improvised on the piano until he got out of me what he felt fitted the pictures. Then I orchestrated it. I had a ball writing pastiche but I composed one deliberately filmic tune I was very pleased with. Two decades later I completely reworked the melody as the title song of Sunset Boulevard which I reconceived in 5/8 time. I’m pretty sure this makes it the only title song of a musical in this time signature. The recording sessions were hassle free and I got back to “Superstar” with the delightful team at Gumshoe seemingly contented. I didn’t hear anything more about the movie for months.

WITH MURRAY AND IAN in the bag as Judas and Jesus, I began firming up our band. Joe Cocker was taking a rest from gigging so Grease Banders Alan Spenner and Bruce Rowland on bass and drums were nabbable. Tim and I approached Eric Clapton’s manager Robert Stigwood in a pie-in-the-sky attempt to procure his client as lead guitarist, but an audience in Stigwood’s grand Mayfair offices ended up with us graciously being shown the door. So we went with another Grease Band member Henry McCullough, who subsequently was lead guitarist in Paul McCartney’s Wings. Chris Mercer, the Juicy Lucy sax player on our single, signed on and brought with him guitarist Neil Hubbard.

Finding a keyboard player, however, was hairier. I needed someone who spanned rock and classical, someone who could play rock by feel but could also stick to the musical script when required, in other words actually read music. There was a progressive trio creating quite a ripple in the sweet smoky haze of the live rock circuit called Quatermass. I can’t remember who first played me their virtuoso Hammond organ dominated tracks but big thanks to them for introducing me to Peter Robinson. Pete ticked every box. Not only was he a great rock player but his musical knowledge spanned everything from Led Zeppelin to Schoenberg, and he introduced me to Miles Davis. Not only was my band complete but Quatermass’s singer John Gustafson became our Simon Zealotes. We were almost ready for the studio.

At the beginning of June we were invited by a Father Christopher Huntingdon to be his all-expenses-paid guests at the US premiere of Joseph. The first-ever public performance of a Rice/Lloyd Webber epic in America was taking place at the Cathedral College of the Immaculate Conception, Douglaston, Queens, New York. Father Huntingdon was in charge of the place. We jumped at it. Neither of us had been to America before. Had I known we would be staying at the Harvard Club in central Manhattan I just might have given my shoulder-length hair a tweak and been spared the censorious looks hurled my way in this epicentre of Ivy Leaguedom.

In truth I remember my first Broadway show better than I remember the Joseph performance which was fine but the Elvis wasn’t up to Tim’s. It was Stephen Sondheim’s Company. I had suggested to Tim that we saw it because I had clocked Hal Prince’s name on the poster. It was a matinee and both afternoon and theatre were stiflingly hot. Somehow I had got into my head that my first Broadway show would be big and brash, at the very least with staging like Cabaret. But of course I saw something groundbreaking and utterly the reverse. I was completely unprepared for it and musically it was a million miles away from what was going on in my head at the time. Tim was taken with the lyrics but I was a 22-year-old in love with a 16-year-old girl and not yet ready for middle-age angst. My rose-petal-strewn state of mind was considerably more the last scene of the same writer’s Merrily We Roll Along than the first.

Back in London Sarah quizzed me about how we got on and I told her about Father Huntingdon and the Harvard Club. She replied that she wished I had told her who’d invited us. Father Huntingdon was her mother’s Ivy League American cousin.