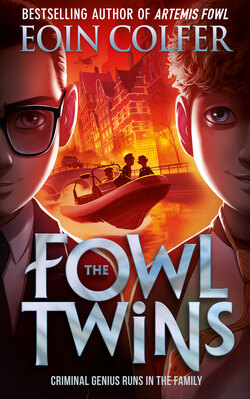

Читать книгу The Fowl Twins - Eoin Colfer - Страница 10

Оглавление

INSIDE VILLA ÉCO’S SAFE ROOM, MYLES AND Beckett Fowl were experiencing a shared emotion – that emotion being confusion. Confusion was nothing new to either boy, but this was the first occasion on which they had felt it simultaneously.

To explain: as the twins were so dissimilar in everything except for physiognomy, it was not unusual for the actions of the one to confound the mind of the other. Myles had lost count of how many times Beckett’s attempted conversations with wildlife had bewildered his logical brain, and Beckett, for his part, was flummoxed on an hourly basis by his brother’s scientific lectures.

So, generally, one twin was lucid while the other was confused, but on this occasion they were mystified as a unit.

‘What’s happening, Myles?’ asked Beckett.

Myles did not answer the question, reluctant to admit that he couldn’t quite fathom what exactly was going on.

‘Just a moment, brother,’ he said. ‘I am processing.’

Myles was indeed processing, almost as quickly as the safe room’s processors were processing. NANNI’s gel incarnation may have been a puddle on the floor, but the AI itself was safe inside Villa Éco’s protected systems and was now replaying footage from a network of cameras slung underneath a weather balloon. These cameras were outside the Faraday cage and, unfortunately, had succumbed to the EMP, but before then they had managed to transmit the video to the Fowl server. NANNI had zeroed in on two points of interest. First, the AI located a dissipating bullet vapour trace and followed it back to the mainland to find that there was a camouflaged sniper there, a hirsute chap with an antique Russian Mosin-Nagant rifle, which would be over eighty years old, if NANNI were correct.

‘There’s the culprit,’ she said from a wall speaker. ‘A sneaky sniper near the harbour.’

This was not the source of Myles’s confusion, as the sonic boom had to have come from somewhere, and, after all, the Fowl family had many enemies from the bad old days. The fact that one enemy would employ an antique weapon could relate back to some decades-old vendetta having to do with any number of the twins’ ancestors, most probably Artemis Senior, who had once attempted to muscle in on the Russian mafia’s Murmansk market. This sniper might simply be on a revenge mission, and what better way to hurt the father than to target the sons?

The second point of interest, and the cause of Myles’s bewilderment, was another, much smaller figure that had been captured by one camera. The tiny creature had appeared out of thin air, pedalled to keep herself aloft and then plummeted into the seaweed silo.

Beckett’s confusion was more general in nature, but he did have one question as the brothers reviewed the balloon footage. ‘A pedalling fairy,’ he said. ‘But where’s her bicycle?’

Myles was not inclined to answer, but was inclined to disagree. ‘There’s no bicycle, brother mine,’ he snapped. ‘And I do not happen to believe in fairies or wizards or demigods or vampires. This is either photo manipulation or interference from a satellite system.’

He rewound the footage and froze the figure in the sky, stepping closer for a decent squint.

‘Magnify,’ he told his spectacles, which he had augmented with various lenses pillaged from his big brother’s sealed laboratory. Artemis had set a twenty-two-digit security code on his door that he did not realise Myles had suggested to him subliminally by whispering into his ear every night for a week as he slept. To add further insult, the numbers Myles had chosen could be decoded using a simple letter–number cipher to spell out the Latin phrase Stultus Diana Ephesiorum, which translated as Diana is stupid, Diana being the Roman version of the Greek goddess Artemis, for whom Artemis had been named. It was a very complicated and time-consuming prank, which, in Myles’s opinion, was the best kind.

‘Yes,’ said Beckett. ‘Magnify.’

And the blond twin accomplished his magnification simply by taking a step closer to the screen, which, in truth, was both more efficient and cost-effective.

Myles studied the suspended creature and it seemed clear that there was, at the very least, a possibility it was not human.

Beckett jabbed the wall screen with his finger, daubing it with whatever gunk was coating his hand at the time.

‘Myles, that’s a fairy on an invisible heli-bike. I am one million per cent sure.’

‘There is no such animal as a heli-bike and you can’t have a million per cent, Beck,’ said Myles absently. ‘Anyway, how can you be so sure?’

‘Remember Artemis’s stories?’ asked Beckett. ‘He told us all about the fairies.’

This was true. Their older brother had often tucked in the twins with stories of the Fairy People who lived deep in the earth. The tales always ended with the same lines:

The fairies dig deep and they endure, but, if ever they need to breathe fresh air or gaze upon the moon, they know that we will keep their secrets, for the Fowls have ever been friends to the People. Fowl and fairy, fairy and Fowl, as it is now and will ever be.

‘Those were stories,’ said Myles. ‘How can you be certain there is a drop of truth to them?’

‘I just am,’ said Beckett, which was an often-employed phrase guaranteed to drive Myles into paroxysms of indignant rage.

‘You just are? You just are?’ he squeaked. ‘That is not a valid argument.’

‘Your voice is squeaky,’ Beckett pointed out. ‘Like a little piggy.’

‘That is because I am enraged,’ said Myles. ‘I am enraged because you are presenting your opinion as fact, brother. How is one supposed to unravel this mystery when you insist on babbling inanities?’

Beckett reached into the pocket of his cargo shorts and pulled out a gummy sweet.

‘Here,’ he said, wiggling the worm at Myles as though it were alive. ‘This gummy is red and you need red, because your face is too white.’

‘My face is white because my fight-or-flight response has been activated,’ said Myles, glad to have something he was in a position to explain. ‘Red blood cells have been shunted to my limbs in case I need to either do battle or flee.’

‘That is soooo interesting,’ said Beckett, winking at his brother to nail home the sarcasm.

‘So the last thing I shall do is eat that gummy worm,’ declared Myles. ‘One of us has to be a grown-up eleven-year-old, and that one will be me, as usual. So, whatever I do in the immediate future, gummy-eating will not be a part of it. Do you understand me, brother?’

By which time Myles had actually popped the worm in his mouth and was sucking it noisily.

He had always been a sucker when it came to gummy sweets. In this case, he was a sucker for the gummy he was sucking.

Beckett gave him a few seconds to unwind, then asked, ‘Better?’

‘Yes,’ admitted Myles. ‘Much better.’

For, although he was a certified genius, Myles was also anxious by nature and tended to stress over the least little thing.

Beckett smiled. ‘Good, because a squeaky genius is a stupid genius. I dreamed that one time.’

‘That is a crude but accurate statement, Beck,’ said Myles. ‘When a person’s vocal register rises more than an octave, it is usually a result of panic, and panic leads to a certain rashness of behaviour untypical of that individual.’

But Myles was more or less talking to himself at this point, because Beckett had wandered away, as he often did during his twin’s lectures, and was peering through the safe room’s panoramic periscope’s eyepiece.

‘That’s nice, Myles. But you’d better stop explaining things I don’t care about.’

‘And why is that?’ asked Myles, a little crossly.

‘Because,’ said Beckett. ‘Helicopter.’

‘I know, Beck,’ said Myles, softening. ‘Helicopter.’

It was true that Beckett didn’t seem to either know or care about very many things, but there were certain subjects he was most informed about – insects being one of those subjects. Trumpets was another. And, also, helicopters. Beckett loved helicopters. In times of stress, he sometimes mentioned favourite items, but there was little significance to his helicopter references unless he added the model number.

‘A helicopter,’ insisted Beckett, making room for his brother at the mechanical periscope. ‘Army model Agusta Westland AW139M.’

Time to pay attention, thought Myles.

He propped his spectacles on his forehead and studied the periscope view briefly for visual confirmation that there was, in fact, a helicopter cresting the mainland ridge. The chopper bore Irish Army markings and therefore would not need warrants to land on the island, if that were the army’s intention.

And I cannot and will not fire on an Irish Army helicopter, Myles thought, even though it seemed inevitable that the army was about to place the twins in some form of custody. For most people, this knowledge would be a source of great comfort, but, historically, incarceration did not end well for members of the Fowl family, and so Father had always advised Myles to take certain precautions should arrest or even protective custody seem inevitable.

‘Give yourself a way out, son,’ Artemis Senior had said. ‘You’re a twin, remember?’

Myles always took what his father said seriously, and so he regularly updated his Ways Out of Incarceration folder.

This calls for a classic, he thought, and said to his brother, ‘Beck, I need to tell you something.’

‘Is it story time?’ asked Beckett brightly.

‘Yes,’ said Myles. ‘That’s precisely it. Story time.’

‘Is it one of Artemis’s? The Arctic Incident or The Eternity Code?’

Myles shook his head. ‘No, brother, this is a very important story, so you will need to concentrate. Can you achieve a high level of focus?’

Beckett was dubious, for Myles often declared things to be important when he himself regarded them as peripheral at best.

For example, some of the many things Myles considered important:

1 Science

2 Inventing

3 Literature

4 The world economy

And things Beckett considered hugely important, if not vital:

1 Gloop

2 Talking to animals

3 Peanut butter

4 Expelling wind, however necessary, before bed

Rarely did these lists overlap.

‘Is this important to me, or just big brainy Myles?’ Beckett asked with considerable suspicion. This was a most exciting day, and it would be just like Myles to ruin it with common sense.

‘Both of us, I promise.’

‘Wrist-bump promise?’ said Beckett.

‘Wrist-bump promise,’ said Myles, holding up the heel of his hand.

They bumped and Beckett, satisfied that a wrist-bump promise could never be broken, plonked himself down on the giant beanbag.

‘Before I tell you the story,’ said Myles, ‘we must become human transports for some very special passengers.’

‘What passengers?’ asked Beckett. ‘They must be teeny-tiny if we’re going to be the transports.’

‘They are teeny-tiny,’ said Myles, not entirely comfortable using such a subjective unit of measurement as teeny-tiny, but Beckett had to be kept calm. He opened the Plexiglas door on top of the insect hotel and scooped out a handful of tiny jumping creatures. ‘I would even go so far as to say teeny-weeny.’

‘I thought we weren’t supposed to touch these guys,’ said Beckett.

‘We’re not,’ said Myles, dividing the insects between them. ‘Except in an emergency. And this is most definitely an emergency.’

It took a mere two minutes for Myles to relate his story, which was, in fact, an escape plan, and an additional six minutes for him to repeat it three times so Beckett could absorb all the particulars.

Once Beckett had repeated the details back to him, Myles persuaded his twin to don some clothing, namely a white T-shirt printed with the word UH-OH!, a phrase often employed both by Beckett himself upon breaking something valuable, and also by people who knew Beckett when they saw him approach. Myles even had time to disable the villa’s more aggressive defences, which might decide to blow the helicopter out of the sky with some surface-to-air missiles, before the knock came on the door.

Here comes the cavalry, thought Myles.

In this rare instance, Myles Fowl was incorrect. The woman at the door would never be mistaken for an officer of the cavalry.

She was, in fact, a nun.

‘It’s a nun,’ said Beckett, checking the intercom camera.

Myles confirmed this with a glance at the screen. It was indeed a nun who appeared to have been winched down in a basket from the hovering helicopter.

If we do nothing, she might go away, thought Myles. After all, perhaps this person doesn’t even know we’re here.

Myles should have voiced this thought instead of thinking it, for, quick as a flash, Beckett pressed the TALK button and said, ‘Hi, mysterious nun. This is Beckett Fowl speaking, one of the Fowl Twins. My brother Myles is here too, and we’re home alone. We’ll be with you in a minute – we’re down in the safe room because of the sonic boom. I’m so glad the EMP didn’t kill your helicopter.’

Beckett’s statement contained basically every scrap of information that Myles had wanted to keep secret.

‘Gracias,’ said the unexpected nun. ‘I shall await your arrival.’

Beckett was hopping with excitement. ‘Myles, it’s a nun with a helicopter! You hardly ever see that. This is the start of our first real adventure. It has to be – I can feel it in my elbows.’

Beckett often felt things in his elbows, which he claimed were psychic. He sometimes pointed them at cookie jars to see if there were cookies inside, which Myles had never considered much of a challenge, as one of NANNI’s robot arms filled the kitchen containers as soon as their smart sensors informed the network they were empty.

‘Beck, with no disrespect to your extrasensory elbows,’ said Myles, ‘why don’t we stay calm and stick to the plan? If we can stay, we stay, but, if we go, remember the story.’

Beckett tapped his forehead. ‘It’s all in here, brother. Angry Hamster in the Dimension of Fire.’

‘No, Beck!’ snapped Myles. ‘Not that story.’

‘Ha!’ said Beckett. ‘You snapped at me. I win.’

Myles counted up to ninety-seven in prime numbers to calm himself. One of Beckett’s pleasures in life was teasing his brother until he snapped. It was unfair, really, as it was very difficult to tell the difference between a Beckett who genuinely didn’t know something and a Beckett who was pretending not to know something.

‘Ha-ha,’ said Myles, without a shred of humour. ‘You got me. You’re the big comedian, and I’m just Myles the dunce. But, in my defence, I am trying to keep us alive and out of an army cell.’

Beckett relented and hugged his brother. ‘Okay, Myles. I’ll lay off this time, because you have no sense of humour when you’re stressed. Let’s go upstairs and you can lecture this nun.’

Myles had to admit that sounded wonderful.

A new person to lecture.

As eager as Myles Fowl was to debate, argue with and deliver a monologue to the mysterious nun, he was determined to take his time reaching the front door. It is always a good idea to keep potential enemies waiting, he knew, as they are more likely to expose their real selves if they become impatient. Beckett was not aware of this tactic, and so Myles had to literally hold him back by hanging on to his belt loops. And thus Beckett dragged his brother along in his wake as a mule might drag a cart.

They passed through the reinforced steel door and climbed the narrow stairwell of polished concrete to the main living area, an open-plan quadrangle marked on three sides with glass walls that were threaded with a conductive mesh, which served both to maintain the integrity of the Faraday cage and reinforce the windows. The reclaimed wooden floors were strewn with rugs, the placement of which might seem random to the untrained eye, but they were actually carefully laid out in accordance with the Ba Zhi school of feng shui. The space was dominated by a driftwood table and a rough stone fireplace that ran on recycled pellets. But the main feature of the villa was the panoramic view of Dublin Bay that it afforded the residents. Myles could remember visiting the island with his father before construction of the villa began.

‘Criminal masterminds are always drawn to islands,’ Artemis Fowl Senior had said. ‘All the greats have them. Colonel Hootencamp had Flint Island. Hans Hørteknut had Spider Island, which was more of a glacier, I suppose. Ishi Myishi, the malignant inventor, has an island in the Japanese archipelago. And now we have Dalkey Island.’

And Myles had asked, ‘Are we criminal masterminds, Father?’

His father did not answer for half a minute, and Myles got the feeling that he was choosing his words carefully.

‘No, son,’ he said eventually. ‘But sometimes you have to fight fire with fire.’

This, Myles knew, was a metaphor, and as a scientist he felt obliged to dissect it.

‘Fire being analogous to crime,’ he said. ‘So, if I take your meaning correctly, you are saying that on occasion the only way to defeat a criminal is to turn his own methods against him.’

Artemis Senior had laughed and tousled his son’s hair. ‘I’m just thinking out loud, son. The Fowls are out of that game. Now why don’t we forget I ever mentioned criminal masterminds and just enjoy the view?’

A view that was utterly ignored by Myles now as he attempted to slow his energetic brother’s trip to their front door. He felt confident that once they reached the door he would be able to argue legal precedent through the intercom with the waiting nun until the cows came home – or at least until he could fill his parents in on the situation. The problem would be how to contain Beckett.

As it happened, this problem never materialised. When they reached the front door, it was already open. The nun had stepped from the rescue basket and was closing her fingers over a hockey-puck-size device strapped to her palm.

‘There you are, chicos,’ said the nun. ‘The door simply opened of its own accord. Increíble, no?’

Incredible indeed, thought Myles. This nun may not be as virtuous as her clothing suggests.

The woman at Villa Éco’s front door was indeed a nun, but her habit was a little more stylish than one would usually associate with the various religious orders. She was dressed in a simple black linen smock that could have indicated that she liked Star Wars films or had just discovered an amazing young designer. The smock was cinched with a wide satin belt that nodded towards ancient Japanese culture. Her hair was too golden to be natural and was arranged in that bouffant style known in salons as 1980s Newsreader, on top of which perched a veil of black polyester secured with a jewelled hatpin.

‘Buenas tardes, chicos,’ she said. ‘I am Sister Jeronima Gonzalez-Ramos de Zárate of Bilbao.’

Beckett didn’t hear anything after the first name.

‘Geronimo-o-o!’ he cried enthusiastically, throwing up his arms.

‘No, niño,’ said the nun patiently. ‘Jeronima, not Geronimo.’

Beckett altered his cry appropriately. ‘Jeronima-a-a!’ and segued into a couple of blunt questions: ‘Sister, why are you red? And why do you smell funny?’

Jeronima smiled indulgently. These were the questions that most people wished to ask but would not. ‘You see, chico, my skin has the slight tinge because of my order: the Sisters of the Rose. We stain our flesh red with a non-toxic aniline dye solution to demonstrate our devotion to Mary, the rose without thorns. And the odour is from the dye. It is like the almonds, no?’

‘It is like the almonds, yes!’ said Beckett. ‘I love it. Can I stain my skin, Myles?’

‘No, brother,’ said Myles, smiling. ‘Not until you are eighteen.’

Myles was less smiley in his attitude towards the nun.

‘Sister Jeronima,’ he said, ‘it would seem that you have broken into our home.’

Jeronima joined her hands as though she might pray. ‘I am a nun. I would never do this. As I think I said, the door was open. Perhaps your EMP affected the locks, no?’

Myles was glad the rose-coloured nun had lied. At least he knew where they stood now.

‘You are, at the very least, trespassing on private property,’ he countered.

Jeronima waved his point away as though it were a pesky mosquito. ‘I do not answer to your country’s estúpido laws.’

‘I see,’ said Myles. ‘You obey a higher power, I suppose.’

‘Sí, absolutamente, if you like.’

‘A higher power in the helicopter?’ said Beckett.

Jeronima smiled tightly. ‘Not exactly, niño. Let us simply say that I am not bound by the rules of your government.’

‘That’s very nice,’ said Myles. ‘But we are not donating today. Can you please call again when my parents are home?’

‘But I am not here for donations, Myles Fowl,’ said Jeronima. ‘I am here to rescue you.’

Myles feigned surprise. ‘Rescue us, you say, Sister? But we are in the safest facility on Earth. In fact, I am disobeying my parents’ instructions by speaking with you. So, if you don’t mind …’

He attempted to close the aforementioned door, but was thwarted by the nun’s left knee-high leather boot, which she had jammed between door and frame.

‘But I do mind, niño,’ she said, pushing the door open. ‘You are unsupervised minors under attack from an unknown assailant. It is my duty to escort you to a place of safety.’

‘I would like to be escorted in a helicopter, Myles,’ said Beckett. ‘Can we go? Can we, please?’

‘Sí, Myles,’ said Jeronima. ‘Can we go, please? Make your brother happy.’

Myles raised a stiff finger and cried, ‘Not so fast!’

It was undeniable that this was a touch melodramatic, but Myles felt justified in indulging his weakness as there was a rappelling nun at the front door. ‘How would you know we are under attack, Sister Jeronima?’

‘My organisation has eyes everywhere,’ said Jeronima with what Myles would come to know as her customary vagueness.

‘That sounds suspiciously illegal, Sister,’ said Myles, thinking he could stall here for several minutes while he winkled out more information about this mysterious ‘organisation’ they were supposed to simply hand themselves over to. ‘That sounds as though you are infringing on my rights, which is unusual for a woman of the cloth.’

Jeronima crossed her arms. ‘I am unusual for a woman of the cloth. Also, I am a trauma nurse, and I once threw knives in the circo – that is to say, circus. But I am not important now. You are important, and it is true what they say about you, chico. You are the smart one.’

‘And I am the one who can climb!’ said Beckett, blowing his brother’s stalling plan to smithereens by vaulting into the helicopter’s rescue basket and scrambling up the winch cable faster than a macaque scaling a fruit tree.

‘And he is the one who can climb,’ said Sister Jeronima. ‘And most quickly too.’ She stepped back and opened the basket’s gate. ‘Shall we follow, chico?’

Myles had little choice in the matter now that Beckett had taken the lead.

‘I suppose we should,’ he said, a little miffed that his fact-finding mission had been cut short. ‘But only if you desist with the fake endearments. Chico, indeed. I am eleven years old now and hardly a child.’

‘Very well, Myles Fowl,’ said Sister Jeronima. ‘From now on, you shall be tried as an adult.’

The gate was already closed behind Myles when this comment registered. ‘Tried? I am to be tried?’

Jeronima fake-laughed. ‘Oh, forgive me, that was – how do you say? – a slip of the tongue. I meant, of course, to say treated. You will be treated as an adult.’

‘Hmmm,’ said Myles, unconvinced. There was some form of trial ahead, he felt sure of it.

Jeronima made a circling motion with her index finger and the winch was activated. As the basket rose into the night sky, Myles glanced downwards, appreciating the aerial view of Villa Éco, which, when seen from above, formed the shape of an upper-case F.

F for Fowl.

Still a little of the criminal mastermind in you, eh, Papa? he thought, and wondered how much of that particular characteristic there was in himself.

However much there needs to be in order to keep Beckett safe, he decided.

With a tap to the temple of his spectacles, Myles activated the infrared filter in his lenses and noticed that, across the bay, the sniper was packing up his gear.

We were not the target, he realised now. A sniper with even one functioning eyeball could have easily picked us off on the beach. So, what were you after, Mr Beardy Man?

He committed this puzzle to his subconscious, to be worked on in the background while he dealt with Sister Jeronima and the other mysterious player in their drama. A player who was now emerging from the seaweed silo – not that anyone but Myles would notice, for the creature, whatever it proved to be exactly, was more or less invisible.

Invisible, thought the Fowl twin. How mysterious.

And as his father often said: ‘A mystery is simply an advanced puzzle. Thunder was once a mystery. A wise man learns from the unknown by making it known.’

And the wise boy, Father, thought Myles now. He magnified his view of the silo creature and saw that a single body part was visible even without the infrared. Its right ear, which was pointed. Somewhere in Myles’s brain, a light bulb flashed.

A pointed ear.

And then the pointy-eared creature began to pedal, and it lifted off after the ascending rescue basket.

Beck was right, thought Myles, glancing upwards at his brother, who was already boarding the helicopter.

It was indeed a fairy on an invisible bicycle.

‘D’Arvit,’ he blurted, shocked that Artemis’s stories had been, in fact, historical rather than fictional.

Sister Jeronima mistook the blurt for a sneeze. ‘Bless you, chico,’ she said. ‘The night air is cool.’

Myles did not bother to correct her, because an explanation would be difficult, considering that the word D’Arvit was a fairy swear word, according to Artemis’s fairy tales.

Myles silently vowed not to use it again, at least not until he knew what it meant exactly.

Lord Teddy Bleedham-Drye was surprised to find his mood brightening somewhat. This would have been a bombshell to anyone who knew him, as the duke was notorious for throwing royal tantrums when things did not go his way. He’d had an emotional hair trigger since childhood, when he would heave his toys from the pushchair if refused a treat. At family gatherings, his father often embarrassed him with the story of how five-year-old Teddy had hurled his wooden horse over the St George cliffs when the nanny served him lukewarm lemonade. And how Teddy had been so antisocial that it had become necessary to send him to Charterhouse boarding school at the age of five instead of seven, which was more traditional among those of the upper class. Now, one and a half centuries later, the duke’s general mood had not improved much, though he tended to take out his frustrations on other people’s property rather than his own and let his irritation fester in his stomach acid. Good form at all times.

And so Lord Teddy was surprised to find himself whistling as he packed his gear.

Whistling, Teddy old boy? Surely you ought to be sinking into your usual vengeful funk.

But no, he was verging on the exuberant.

And why would that be?

It would be, Teddy old fellow, because there is something afoot here. I take a single shot and suddenly the army is swooping in for an extraction?

The Fowls were an important family, but not that important.

The island was obviously under the surveillance of some agency or other.

This confirms my growing certainty that Brother Colman’s lead was sound.

Now Teddy had a choice: he could continue to stake out the island and wait for another troll, or he could follow the Fowl children and find the troll he had wrapped earlier.

Lord Bleedham-Drye knew that, logically, he should maintain his surveillance on the soon-to-be-unguarded Dalkey Island, but his instinct said follow the Fowls.

The duke trusted his instinct; it had kept him alive this long.

After all, it would be child’s play to follow the troll, for each Myishi CV round was radioactively coded, and Teddy had programmed the individual codes into his marvellous Myishi Drye wristwatch, which had over a thousand functions, including geo-pinned news alerts and actually telling the time. The Drye series was the gold standard in criminal appliances. It included watches, exercise machines, a gorgeous porcelain handgun, a line of lightweight bulletproof apparel, a light aircraft and a range of communication devices. Each item was embossed with a copy of the famous Modigliani line portrait of the duke from 1915. In return for his sponsorship, Teddy had a yearly credit of five million US dollars with the company, and a fifty per cent discount on anything above that amount. The slogan for the Drye range was Stay Drye in any situation with Myishi. It had been a most successful arrangement for both parties. And, in truth, Lord Teddy would have long since declared bankruptcy without the Myishi Corp sponsorship deal. For his part, Ishi Myishi had the seal of approval from one of the most respected criminal masterminds/mad scientists in the community, which shifted enough units to easily pay the duke’s tab.

Good old Myishi, thought Lord Teddy now, and his marvellous gadgets.

The duke and Ishi Myishi had been associates as man and boy. Or, more accurately, since Myishi was a boy who had lied about his age to join the Japanese Army and Teddy Bleedham-Drye was a British Army officer. The duke had discovered young Myishi breaking out of a prison shed in Burma, defending himself with a shotgun the lad had cobbled together from the frame and springs of his cot. Teddy recognised genius when he saw it and, instead of turning the boy in, he’d arranged for him to study engineering at Cambridge. The rest, as they say, was history, albeit a secret one. By Teddy’s reckoning, Myishi had repaid his debt a hundred times over.

Make that a hundred and one, Teddy thought, for one of the duke’s sponsorship perks was a hunter-tracker system that could be bounced off several private satellites. And so, wherever in a several-hundred-mile radius that troll went, Teddy could easily follow.

The Fowls will never hear me coming, he thought. And they will never hear the bullets that kill them.