Читать книгу The Navigator - Eoin McNamee, Eoin McNamee - Страница 10

CHAPTER SIX

ОглавлениеOwen woke early the next morning and ran straight to the Workhouse without even a drink of water. He ran up the stairs and into the main hallway. Even though people were busy, moving with purpose, he saw more than one curious glance cast in his direction. He found the stairway that led to the kitchen and plunged downwards. When the stair opened out into the kitchen he found it calmer than the previous day. The great ovens were glowing and many huge pots were simmering on them. He saw Contessa and he half walked, half ran over to her. She turned to him. Her face was grave, but she spoke before he did.

“Cati will recover, Owen. I think you saved her. But only just. I had to put her back to sleep in the Starry. She was frozen to the very core of her being. I am suprised that you were not. Perhaps you have a special resistance.”

“I was cold,” he said. “Freezing.”

“The cold they emit is not just physical, Owen. It freezes the very quick of you. Your soul. You’re very strong.”

“Strong,” said a voice. “You’d be good and strong maybe. But maybe they had fair cause not to freeze you. Them ones could have had cause to spare you.”

Owen turned to see a tall, thin youth with a solemn face. His trousers were torn and on top he wore something that might have been a shirt at some time, but now was so ripped and dirty that it could have been anything, and was certainly no protection against the cold morning air. When Owen looked down he saw that the boy’s feet were bare.

“Wesley,” Contessa said sharply, “I won’t have malicious gossip repeated in my kitchen.”

“It’s what people do say,” Wesley said, but he grinned in a mischievous way and stuck out his hand. Owen took it and Wesley shook his hand vigorously.

“Wesley,” he said. “I do be one of the Raggies. I brung fish for the lady Contessa.”

Owen looked down for the first time. There were perhaps twenty boxes of fish on the ground around them, bringing with them a smell of the sea.

“I have an idea,” Contessa said. “There are those who wish to ask you about last night, and their thoughts are not kindly for the moment. You would be better out of the way. Would you take him to the Hollow with you, Wesley?”

“I will, lady.”

“I want to see Cati,” Owen said.

“She is asleep,” Contessa said, suddenly seeming taller, her eyes glittering with a dangerous light. “Are you not listening?”

“Come on,” Wesley said cheerfully, pulling at Owen’s sleeve, “before the lady do devour the two of us.” Contessa didn’t say anything and her eyes were like stone, but as they walked away with a chirpy “Cheerio, lady!” from Wesley, Owen thought he saw the ghost of a smile tugging at the corner of her mouth.

Wesley walked quickly, even in his bare feet, and Owen had trouble keeping up. They left the Workhouse and Wesley started on a path which followed the river down to the sea, curving towards the town and the harbour. At first, Owen fired questions at Wesley, but the boy only turned and grinned at him and pressed on even harder. They came to the place where a new concrete bridge had crossed the road between the town and his house, but there was no bridge and no road. Owen climbed up the riverbank. Despite everything he had been told, he still expected to see the familiar streets of the town.

The town was there, but with a sinking feeling Owen realised that it looked as if it had been abandoned for a hundred years. The houses and shops were roofless and windows gaped blank and sightless. The main street was a strip of matted grass and small trees, and ivy and other creepers wrapped themselves round broken telegraph poles. Where new buildings had once stood there was bare ground or the protruding foundations of older buildings. The rusty skeleton of what had once been a bus sat at right angles in the middle of the street. A gust of wind stirred the heads of the grasses and the trees, and blew through the bare roofs of the houses with a melancholy whistling sound.

Owen slipped back down the side of the bridge. The town was starting to crumble back into time, taking with it the memory of the people who had once walked its streets. He remembered what Cati had said about living things growing young, but the things made by man decaying as time reeled backwards.

“Never pay no mind,” Wesley said gently. “That’s just the way it is now. All them things can be put right, if we put old Ma Time back the way she should be, running like a big clock going forward. You just stick with us. We’ll put all yon people back in their minutes and hours, and Ma Time, she’ll put us boys back to sleep again. Come on,” he said, lifting Owen to his feet, “let’s get on down to the harbour.”

This time Wesley walked alongside Owen. The water in the river got deeper as they approached the harbour and Owen found himself veering away from it, which Wesley noticed.

“That’s what I heard,” he said, with something like satisfaction, “that you can’t abide the water.”

“Who told you that?” demanded Owen.

“They was all talking about it,” Wesley said, “that the new boy, Time’s recruit, did fear the water.”

“I don’t like it too much,” Owen said.

Wesley rounded on him sharply, his face close to Owen’s, his voice suddenly low and urgent.

“Do not be saying that to anyone. No one. Do you not know? I reckon not. The Harsh can neither touch nor cross any water – not fresh nor salt – and the touch of it revolts them unless they can first make ice of it. If any see you afeared of water, they will think you Harsh or a creature of the Harsh.”

Owen remembered how the long-haired man, Samual, had reacted when he had seen Owen’s foot touch the water. “I think they know already,” he said slowly.

“Then it will be hard on you,” Wesley said. “it will be fierce hard.”

“You don’t think I’m one of the Harsh, do you?” Owen said. His voice trembled slightly, but Wesley just threw his head back and laughed.

“Harsh. You? No, I don’t think you’re Harsh. I think you’re like one of us, the Raggies. You been abandoned and the world treats you bad, and even though you ain’t as thin as Raggies, I do know a hunger when I see it.”

Owen didn’t expect the harbour to look the same and he wasn’t disappointed. The metal cranes were twisted and rusted. Most of the sheds had gone and the fish-processing factory was a roofless shell. The boats were still tied up, but it was a ghost fleet. The metal-hulled boats lay half sunk in oily water. The wooden boats had fared better and some of them still floated, but the paint had long faded from them, and their metal fittings had all gone.

“It’s like they’ve been abandoned for twenty years,” Owen said.

“Longer than that,” said Wesley. “Ma Time, she goes back more fast than she goes forward.”

Thinking about time made Owen’s head hurt. He looked back the way they had come. He could see the slateless roofs of the town, then a white mist where the Harsh camp was, and beyond that, the mountains that hemmed the town into this little corner of land, their tops white with snow. He realised that Wesley was making for the area of rundown warehouses that was always referred to as the Hollow. As they got closer, going out on to what Owen knew as the South Pier, but which now seemed to be a causeway over dry land, he saw that the buildings had not changed at all. There were five or six stone-built warehouses with empty windows in the front of them. Owen thought he could see rags or cloths in each window. As he looked, many of the rags started to stir, and then he realised that each one was a child or young person dressed the same way as Wesley. A shout went up from them and Owen thought that there was dismay in the sound. As they closed in rapidly, he saw that they were looking out to sea. Wesley said something under his breath and climbed the parapet of the South Pier. Owen followed.

At the top, Wesley stood staring out to sea, his hand shading his eyes. About half a mile from shore Owen could see a boat, but it was not like any he had ever seen before. It was an elongated shape, copper-coloured, but with high sides that curved in at the top, and a single tall mast with what looked like a small crow’s nest at the masthead, topped with one of the blank black flags he had seen at the Workhouse. In each side of the boat there were five round holes, and in each hole there was a long, spindly, coppery stick, too long and thin and delicate, it seemed, to be an oar. But as Owen watched, the sticks started to beat violently and the whole craft was suddenly lifted on them and propelled at speed across the top of the water. Owen thought it looked like the insects you saw on ponds, the ones that walked on the surface of the water. The craft splashed back into the water, the sticks beating slowly this time, then it rose and shot forward again.

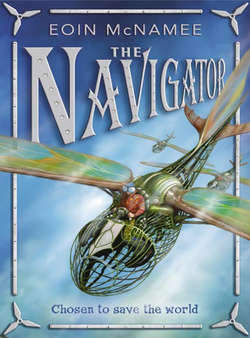

“Look!” Wesley shouted. Owen followed his outstretched arm. High in the sky above the strange boat, Owen saw three shapes. At first he thought that they were birds then he realised they were much bigger. One of them detached itself from the others and dived towards the boat, swooping down in great circles, and Owen saw it was an aircraft of sorts, with two impossibly long and delicate wings that beat slowly. The body of the aircraft was like a very fine cage with a long fin at the back, and at the centre sat the figure of a man, crouched over a set of controls and staring down at the boat through huge oval goggles.

As the craft wheeled over the boat, the vast feathery wings glittered with a metallic sheen. Then a blaze of blue light shot from the body of the flying craft and struck the water beside the boat. There was an immense sizzle, and the boat disappeared momentarily in a cloud of steam and spray. When it reappeared Owen saw ragged children clambering frantically over the superstructure of the vessel. Baskets of fish were being passed up at great speed from the depths of the hold and flung over the side. Another of the flying craft swooped on the boat, closer this time. Owen felt sure that the flash of light would hit it, but at the last moment, the beating oars raised the hull from the water and flung the boat forward with such violence that it swerved to one side, almost out of control. Once again it emerged from a cloud of steam and spray, but this time there was a long burned streak down its side, and one of the oars hung broken and useless. When it made to move forward again, it began to slew to that side.

“They’re dead, dead to the world,” Wesley said softly. “They cannot make it ashore.” His face was white with fear.

But then a strange thing happened. Owen became aware of a great shrieking. The water around the delicate vessel was covered with the fish that had been thrown overboard and seabirds were converging on the unexpected meal, thousands of them it seemed – herring gulls, black-headed gulls, black cormorants. Within a minute there were so many gulls that Owen could barely see the boat. The spindly aircraft were buffeted in the air by the beating wings of so many birds, and then they too became invisible. More and more gulls blanketed the ocean. Owen could not see the boat, but it seemed that it was still under attack. There were flashes of blue from within the swirling flock and there were dead seabirds among the thousands that squabbled for the floating fish.

Minutes passed and then a great cheer went up from the anxious children onshore. On the very edge of the flock of seabirds, the prow and then the rest of the boat emerged. There were children standing on its deck, some of them sitting along its rail. Many of them were very young, pale and frightened, but the tall, freckled girl at the tiller looked defiant.

The oars beating slowly, the boat swung in against the quay and the girl leapt lightly on to it. Wesley went over to her. Owen followed, hanging back a little. He could see the long scar running down the side of the boat.

“They near got us,” the freckled girl said.

“Birds saved your hide,” said Wesley.

“That was a good idea, throwing out the fish,” Owen said. The girl looked at him curiously.

“That him?” she said to Wesley. Wesley nodded. The girl stuck out a hand. Her eyes were a curious greenish colour and she was wearing oily overalls. “Silkie’s my name, and I only threw out the fish for to save weight. I never thought about the birds.”

“Is she broke?” Wesley said, looking anxiously at the boat.

“She’s all right,” Silkie said. “She has a bit of a burn on her, but she’ll sail again. The little ones is scared though. Them Planemen was never that brave before; they come pretty close.”

“I do think the Harsh is stronger this time and they do push Johnston harder.”

“Johnston?” Owen said. “The man who has the scrapyard? I was playing there once and he chased me with dogs.”

“It’s a good thing he chased you with nothing worse,” Wesley said. “Johnston is a terrible cruel man.”

“A man though,” Owen said. “Not one of the… the Harsh?”

“No,” said Silkie. “You know the way that the Sub-Commandant is the Watcher, staying awake through the years until the Harsh return and it is time to wake the others to fight?”

“I think so,” Owen said.

“Well, Johnston is a Watcher too, except that he watches for the Harsh and makes sure that all is ready for their return.”

“His own men sleep in their Starry and he wakes them for the Harsh,” Wesley said, “The Planemen you seen attacking – they’re his men.”

“I’m starving,” Silkie said.

“You’re always starving,” said Wesley with a grin, “but you do deserve something to eat for the fright you got from them Planemen. Come on.”

Wesley led them into the nearest of the buildings. The ground floor was completely open with a big hearth at one end where a fire of driftwood crackled, a sweet smell of burning wood drifting through the room. A long table with benches on either side stood in the middle. There were children everywhere, all of them dressed poorly. Some of the smaller ones walked straight up to Owen and stared at him with large solemn eyes. The older ones climbed quickly up and down the ladder which led upstairs, or perched in the high windowsills.

Despite all the young people milling about, Owen realised that there was a sense of order. The table was being set with flat wooden plates and food was being carried in. Within minutes all the Raggies had seated themselves round the table and the older ones were serving food. Owen was put at the top of the table, beside Wesley and Silkie. Every plate was full, but no one moved to touch it. It wasn’t until Wesley pulled his plate towards him that the children grabbed their own and began to eat hungrily. Owen realised that he too was starving. There was fish and fried potatoes. He tried them and thought they tasted like fish and chips. The noise in the room died to a murmur as everyone concentrated on the food in front of them, eating rapidly with both hands.

Within minutes, every plate was empty. While the younger children carried out the crude wooden plates, Wesley, Silkie and Owen moved over to sit on the rough stone of the fireplace. As they did so, others sat on the floor in front of them or gathered on the ladders and windowsills. The sun shone through the windows and dust motes floated in the beams. Owen felt warm and full and surprisingly contented. He realised that the children were watching Wesley expectantly.