Читать книгу Invisible Men - Eric Freeze - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

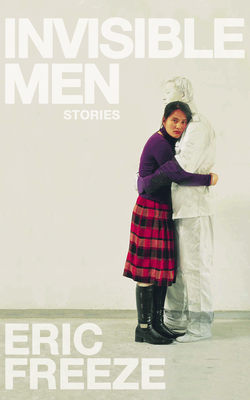

The Invisible Invisible Man

ОглавлениеFred had flux on his fingers. It was lead-free, self-cleaning, from a red-and-white tin the size of a can of shoe polish. He’d tried the brush that came with the kit but the clumps had refused to spread out the way he wanted them to. It was cold. Pipe-freezing cold. He needed his fingers to warm the metal, so the flux would go on smooth.

Fred pushed a coupling into place and eased open the gas torch. He lit the flame with a lighter. Bits of solder stuck in the nozzle like tiny silver fillings. The blue flame was lopsided and he hoped it burned hot enough. He angled the torch down at the mess of copper he’d constructed on the basement ground, propped up on old pipes with their inch-long gashes where the metal had flowered open from the ice. The blue flame split at the ¾-inch tee joint and wrapped around either side like a tiny pair of ethereal tongs. Then he waited.

The flux went soft and melted and kind of bubbled at the edges but when Fred touched the unwound solder to the joint it stuck and beaded like a little ball of mercury. It wouldn’t suck into the joint. The bright copper turned an agate color and the sticker with the bar code flamed and became a dark smudge. He pushed the solder into the joint again and again but the blobs nicked off the copper and fell like ball-bearings to the dirt floor. Maybe he hadn’t got all the water off. Maybe it was just too damn cold. The soldering had worked for the ½-inch but it had dripped into the torch nozzle and the bigger, ¾ joint wasn’t budging. Fred touched his fingers to the end of the pipe to melt off the excess flux and get his fingers warm again.

Two hours earlier he had been in his office faxing an offer on a brick Greek revival for one of his clients. It was a cherry place with a yuppie stainless kitchen, Viking stove and original moldings from the turn of the century. It had been on the market for two years, dropping a couple thousand with every downtick of the S&P, and the offer was a fraction of what the place was worth on paper. Didn’t seem right somehow. And now here he was saddled with his own property, a Christmas foreclosure, a rental he’d snatched up for a little more than what you’d pay for a car. He’d forgone the inspection because there was a bidding war and the place had been recently renovated. No contingencies. Now here he was. Fluxed hands. Cold. And money hemorrhaging out of him like blood from a new wound.

Fuck it, he said.

At the hardware store, he stood with a clerk in front of a shelf of new torches. This one, the clerk said, 30% faster, automatic ignition. That’s what you need, a hotter torch. Fred took it and went to the till and swiped his card and signed on the electronic line and within half an hour was back in the dark basement sixty bucks poorer.

But the clerk was right.

The flame was a brilliant blue, about an inch wide. It feathered out at the edges and when he put it to the joint it covered the copper in a wash of translucent blue. He waited ten seconds to be sure before moving in with the solder. It sucked in immediately and the excess dripped and splattered on the floor. Smoke poured from the open ends of the pipe, and for a moment, Fred was happy.

He fluxed the burnished ends of the old pipes and fit the welded piece into place. The coupling was just outside the slatted wood covering an old crawl space, and the February air blew hard through the gaps. Maybe that’s what did it. He’d have to get some spray foam insulation or they’d burst again for sure. Maybe wire-wrap, even. Always something that cost more money. But, for now, the pipes. He unwound the solder so there was plenty to push into the joint and then clicked the torch on. It felt good not having to light the thing, flame on, like the Human Torch. He lifted the flame to the coupling and caught a bit of the beam behind it. There’d be some charring, no big deal. Seven seconds this time and he pushed the solder in and it dripped around the joint and he was done.

He shut off the torch but the flame on the wall had picked up and was going strong. He pulled his coat sleeve over his hand and beat at it. The sleeve came back hot and charred. The flame started curling up the slatted wood, fed by the cold air. He would need water now, and lots of it. Fred clattered down the aluminum ladder and ran to the water main and turned the valve and heard it filling the pipes. He hadn’t soldered the other side of the patch and bursts of brown water sprayed from the joint. He jumped up and yanked hard but had no control; the water was at least a foot from where it needed to be. Fred moved the ladder and climbed up and held his thumb over the pipe and angled the flow as best he could at the growing flames. There. The flames hissed and smoke filled the air in wooly billows. Fred covered his mouth with his sleeve, trying to avoid his fluxed hands and he climbed the crumbled steps to the bulkhead doors and threw them open.

Outside he sat down, dizzy. He’d inhaled several lungfuls of smoke and felt like an asthmatic trying to get his breath back. He breathed through his nose and the cold set in his chest. His jeans were muddy from the knees down and the flux saturated the sides of his thighs where he’d wiped off the excess. His parka had silver stars of solder burned into it and the one sleeve was blackened. If Donna drove by right now, she’d see a bum, a little on the heavy side, face smeared with grime, sitting in front of his cheap-ass house on his frozen lawn. It would confirm everything she’d told him, how he was the kind of guy who could fuck up winning the lottery.

The smoke cleared. Not a bit of charring on the outside, protected by all that aluminum siding. Fred lumbered back down the steps and took his bearings. Moisture hung from the joists in beads. If he didn’t get these pipes fixed, didn’t get the water on and call the utilities to hook up the gas, they’d freeze that way, like little transparent teeth.

The charred wall was still steaming and the blackness spread out in a fan. At the center where he had pointed his torch was a hole the size of a quarter. And through this hole, light. Without thinking, he pulled the fabric of his parka over his hand and punched into the weakened wood. More light. He pulled off chunks of charred wood until the slats grew thick again and he had trouble getting it to budge. It was a crawl space. He went to get a pry bar.

He couldn’t tell at first how large it was, but the bar made quick work of the planks and Fred could see it had probably been put there after the house had been framed. The brick foundation leveled off to a dirt floor that was damp and smelled like moss. Weak light checkered the ground underneath an iron grate that Fred recognized from the back yard. What he thought was a drain was actually an old cistern. He made his way in but had to stay low, hunched over. The walls were worn concrete, ragged, exposing the brick beneath like moths had eaten its surface. The ground was soft and that meant moisture. He wondered if he’d have to fill this space in with gravel or sand. Another few hundred bucks down the drain.

The house had been his idea, not Donna’s. Donna was never on board. But even if they only had renters half the time, he calculated, over the next five years they’d still come out ahead on their loan. It’d be a long-term investment, just five years and it’d keep paying a profit. That was what he kept telling her, and later, what he kept telling himself. Long term. Who cares if they couldn’t make payments for a few months? It was a temporary pinch. A pinch and then a release of money filling up the coffers.

He scooted feet first along the dirt floor when his boot caught something. From the texture on the surface—a rough, mottled gray—he had thought it was a rock partially buried in the soil. But he pried up a corner with his shoe and some of the dirt fell loose. Then he kicked at it, heel first. A tarnished button. Denim. He continued to kick and then pushed out the entrance and reached back in to grab and pull it out. The material was faded blue and splotched with oil stains and dirt. But the shape was unmistakable: a pair of crumpled overalls. And they looked to be his size.

Fred took them home. To his tiny home. He’d been alone now for three months. In a way, he wondered if the new-to-him house was to fill the void. Something to take up the time, so that instead of eating dinner over the kitchen sink, or watching TV in the dark, he could be over in the basement soldering copper, flux on his hands, wiped in snot-like streaks on his pants. Or maybe it was to make up in the areas where he felt inadequate. He’d never made a lot of money, not even during the boom. But this would change everything. Property management. His chance to make an investment. A little elbow grease and then rent it out for double the mortgage. Or flip it for twice what he paid. It was a risk he was willing to take. If he didn’t burn the place down in the process.

Fred put the overalls in the washing machine in the basement. He could use a pair, especially for plumbing. The overalls had only a couple pockets, but they’d keep the grime off, like a second shell. He stripped down, turned off the lights, and chucked the rest of his work clothes in the washer too. Sometimes when Donna was on her period he’d come down here and jack off. He’d wipe up his semen with dirty clothes and then put them through the wash and hope she couldn’t smell it on him when he came upstairs. Now, in the darkness, he sat in a hamper full of clean laundry and his heavy body felt limp and deflated. It should’ve been enough for him, this house. It was small but they had worked hard for it, calculated their monthly bills and then insulated and weather-stripped the thing so it cost them hardly anything to heat. It was a bungalow. He loved that word: bungalow. It seemed to capture all the middle-class optimism of a first home. And now he had bungled it. Bungled the bungalow. When the buzzer went off he snaked the intertwined laundry from the top-loading washer to the front-loading dryer. With the dryer door open, there was just enough light to change into a pair of flannel pajama pants and a t-shirt.

Upstairs, the kitchen was dominated by the fridge. Donna’s request. The 29-cubic-feet monstrosity dwarfed the plain oak cupboards. Because of the ice dispenser plumbing in the back and its four-inch-thick door, the fridge stuck out like a giant stainless steel monolith in a too-tight doorway. He thought of getting drunk. He’d been saving a six-pack of Coronas and he reached through the long necks for the yellow handle and pulled them all out. They’d get warm, sure, but he didn’t want to have to go back to the fridge. He had a date with the couch. And the Sci-Fi channel, maybe Stargate or Battlestar. Something to take him out of this world.

The next buzzer sounded hollow. He meandered downstairs to the dryer, where he pulled out the clothes and carried them to his room. He dropped them on the floor in wadded clumps and sifted through for the overalls. His new find. With the new-to-him house. Free. Along with the stress of busted pipes and repainting and removing years of hard water and soap scum from the shower. Hanging from his hands the overalls made him think of those dustbowl photos, depression-era Joads. They were a grayish-blue denim, faded around the knees. He looked for some sort of tag or initials or symbol in the rivets. But there was nothing. Just oil stains that darkened the denim in cloudy spots the size of plums. What the hell, he thought. He put them on. One leg, then another. The overalls didn’t look to be that long, but he couldn’t see his feet through the other end. He stood up and instantly felt the beers, all six at once it seemed like. His head was a pressure cooker about to go, the world shook, the edges of his vision were blurred and indistinct. It was like going cross-eyed, two fields of vision separating, and his eyes straining to merge them again. Was that his hand? That white shape between him and the mirror at arm’s length? Whatever it was, it was fading, along with his lumpy torso. He sat on the bed and his shoulders tingled like he’d slept on an artery and the blood was just now starting to circulate again. And his head. He held his hand to his forehead, like he was checking himself for a fever. His vision was still getting worse. All he could see were the mocha walls of his apartment, and, before his body fell back against the bed, the crisscross of denim from the back of his overalls.

He woke in the morning with lines of light striping the room through his mini-blinds. At some point he had pulled his feet up and rolled onto his side facing the window. The light was hitting him right across the eyes and he pulled his pillow over his head and shifted to his other side. He would get up now, headache or no headache. Even if there wasn’t much to get up for. Besides the yuppies, he didn’t really have any clients. A couple of perpetual window shoppers and one investor looking for foreclosures like the one he just bought. And the MLS was dead, no new listings in the city, not much even in the region. That left the house. The house and his botched plumbing job. The house he had almost burned down last night. If only he had burned it down and could find a way to blame it on someone else. It was worth twice as much in insurance as it had cost him.

He sat on the edge of the bed, his dry eyes open in slits, and looked in the mirror.

Nothing.

He opened his eyes fully and the room came into focus. There were the triangular wall sconces, the beveled mirror, his dresser top with a broken watch, a bowl of coins, wadded gum wrappers and a stray sock. But nothing there, here, where a person should be, a self. Just a pair of rumpled overalls, the straps looped loosely over nothing. He stood up. The overalls stood up. He twisted his torso from side to side. The overalls corkscrewed, bunching around the middle. He bent over. The overalls bent at the waist, an open maw of emptiness. Son of a bitch. He slapped his face, jumped up and down. Nothing. Huh. He went to eat some breakfast.

In the kitchen, between bites of Grape-Nuts, he experimented with the overalls. He tried one leg in, one leg out, and his body faded down the middle like it had been airbrushed away into nothing. He drank his orange juice and had to use two hands to steady the cup that seemed to will itself through the air to his lips. It was like his body was one large phantom limb. In the shower, overalls off, his skin reappeared and the water went slick over his arms. The threads shot from the nozzle and his arm hair flattened where they hit and flagellated with the current. He held up his hands. They were wrinkled around the whorls of his fingertips, whitish. But when he dried and changed back into the overalls it was like a light had gone out. A relief, somehow, to be without himself.

In his Taurus he expected to turn heads. For once be the guy that everyone was looking at. Or through. Maybe even cause a panic. But on the street and even at stoplights, people kept their eyes straight ahead. They yakked on cell phones, tapped fingers on steering wheels. He was the invisible invisible man. The office was empty when he arrived, most of the realtors out with clients, the way it should be on a Saturday. He ambled to his office, plopped down in his ergonomic chair. He logged on to his computer under the pretense of doing work. He checked the MLS and a couple realtor blogs to try to keep his focus. But in a few clicks his browser was open to tinychat.com and his webcam window showed his swivel chair and his empty overalls. He created a new profile as “Invisiman” and scrolled through the other lonely souls looking for someone to talk to. The first month after Donna left all he had felt was sorrow. He still fantasized about getting her back: the house and its jackpot-potential leading to his own kind of coronation with Donna at his side. Meeting people online was like a warmup run, or dating for dummies. It let him make the mistakes so he wouldn’t make them again when he tried to woo her back. There were only a few chat sites that the firewall at work didn’t block. Of them, Tinychat was the only one that allowed you to search by location; you could narrow it down to the few people logged on in Indianapolis and chat with them while they sat in their living rooms or hotels or internet cafes or at work. He’d found Donna on there a few weeks ago. She had a list of friends, the screen name “Indyhottie277” and a description of pastimes and interests that were almost inimical to his own. He remembered looking at her picture, knowing that with one click he could be face to face with the woman who left him. Seeing her there, her name and personality and photo reduced to a thumbnail icon, he experienced a kind of jealousy. Like he’d walked in on her and a lover but the lover was in the bathroom. Or he was the lover, the potential lover, looming in the doorway. A few keystrokes and he found her profile again.

She wasn’t on.

He sat back in his seat. He tried to think what had set Donna off. Couldn’t have been the job. She always said those things weren’t important to her. Had they simply gotten too used to each other? Diverged in ways he didn’t comprehend? There were warning signs. Like the teeth, his clicking teeth. He’d been eating his cereal, the way he had for years, a nest of wheat puffs and 2% milk. But when he brought the spoon to his mouth: a silence, then a kind of gasp. Donna had been sipping her coffee, two handed, her butt against the counter, watching him.

“Stop it,” she said.

Fred spooned more puffs into his mouth and crunched away. “What.”

“Never mind.”

So he did. He didn’t mind. He ate his cereal one spoonful at a time, his spooning and chewing and swallowing filling the space. She held herself rigid the whole time. It was only later when he heard her on her cell that he found out. He’d turned on the water for a shower then cracked open the door to their bedroom to watch and listen. It was perplexing, Donna and her hang-ups. She was always on, like a contestant in some reality TV show, always conscious of the camera. She strode around their bed, her cell against her ear. Her head bobbed up and down and when she flung her hair back, she flicked the curl of her bangs so you could see her eyes pooling.

“He clicks his teeth,” she said into the phone. “Over and over. Like a horse.”

In the shower he wondered what she meant. Clicks his teeth. Were they clicking against something? Like the spoon? Or did she mean clicking them together, teeth on teeth, as he chewed? For days afterwards it was a strain for him to eat. He’d hold the spoon in his hand like a parent waiting to feed a child. With the spoon finally in, he was aware of every muscle conforming to its shape. He tried to slide the food off without letting his teeth touch it. And chewing, forget it. Most of the time he just swallowed like he was downing prescription pills.

He found another woman to chat. The most anonymous he could find. No birth date and no interests other than “yes.” Hair: yes. Eyes: yes. Interests: yes. Sex: yes. The picture was a placeholder icon of one of the Powerpuff girls, a red-head. There was no video, no audio. So he typed, “Are you a man or a woman?”

“Yes.”

“What a relief.”

“Yes.”

“I found a pair of overalls that turns me invisible.”

The Powerpuff girl gave him the boot.

Fred nosed his Taurus onto Jefferson Street and parked beside the house. Time to work. Nothing like rejection to solidify his resolve. He was Invisiman. Invisiman got out of the car. Invisiman walked through the berm of snow at the curb and up his unshoveled sidewalk. Invisiman unlocked the bulkhead doors. Invisiman went to work in his basement. After just a few minutes, he almost didn’t react anymore when a four-foot length of copper pipe levitated into the air. What started as a kind of ethereal spectacle became routine. He sanded and burnished the ends with what looked like a floating emery cloth and the flux seemed to glide itself onto the fittings. The torch hovered at the coupling until the flux bubbled out, then the solder sucked in on its own. It was like watching an instructional video for plumbing. You could see every detail so clearly. But the best was his torch. The Bernzomatic. Flame on, flame off. Invisiman contemplated torching the place. No. He wanted a witness this time, someone who would see that this was the work of Invisiman. He set the torch down and pulled out his phone.

Donna hadn’t yet changed her number, though she’d threatened to if he didn’t stop. After a while she simply didn’t answer, and didn’t return his messages. He hoped now that it would be long enough. He dialed the number and counted the rings. No answer. He called again, this time waiting for the beep, her voice mail. “Donna, it’s me. I know you don’t want me to call. I’m at the new house. In the basement. The pipes are frozen and I think I might set the house on fire. This isn’t a threat—don’t think of this as a threat. I’m just tired and it’s freezing cold down here and I don’t have anyone—” Another beep sounded and Fred held the phone away from his face, a metal and plastic slab levitating in front of him.

To talk to. He stopped short of saying the words. He sat down on the cement, still damp from when he put out the fire yesterday. The cold and wet seeped into the overalls, through the boxers to his skin, or whatever it was he had now. He could stay here, how long? A week before anyone would notice? At work they’d think he was finally out with clients, showing homes like his license said he should. He had friends, sure, but they were mostly couples and it was awkward with them now. They were standoffish, as if his marital troubles were contagious. His only obligation was an eye exam on the 28th, and that was in a few weeks. A few weeks of lying here in the dark, absorbing moisture and cold, his body temperature plummeting, and then he’d be a frozen fixture of the place. Maybe that’s what happened to the previous owner: he went into the crawl space, lay down and decomposed into the ground. Just the overalls left. But an ending shouldn’t be so pathetic. Not for Inivisiman. He got up and walked outside.

The wet spots felt like ice through the overalls. He wasn’t going to last long out here, not at night with the wet and the chill. But he wanted to see if Donna would come. He had left messages before, pleas for afternoon walks or movie nights, but usually to stave off boredom—never with that degree of desperation. He hoped she picked up on it. He replayed the words in his mind and tried to imagine how it would sound. The reception would be poor in the basement, but even through that she would hear the resignation in his voice. She would come, drive up into the yard, not stopping until she’d taken him from the basement. Talked some sense into him. Invisiman huddled in the bushes in his overalls and the branches speared his arms. At least he could still feel that. The numbness hadn’t reached through his core yet. He had twenty minutes, he figured, before he’d have to trek back inside. Would she come? He folded his invisible arms then lifted one of his hands up to press it to his cold ear. Just the tips were tingling now. She would come. She had to.

Invisiman started to shake. His jaw was sore like he’d been grinding his teeth all night. He wondered if he could measure the cold by the regularity of his convulsions. Cars winked past, their headlamps illuminating the bushes and leaving the fading red glow of their taillights. He would look like just a pair of stiff overalls hung on some branches but refusing to move with the wind. The shaking began to subside and an oddly warm numbness started in his fingers and worked its way slowly up his arms and to his body.

He had the urge to run.

He rolled himself out of the bushes and then he was down the steps to the icy sidewalk. He crunched through the snow and managed a kind of dull shuffle, kicking up little chunks of ice that had frozen around old footprints. It couldn’t be too late yet, maybe seven or eight, but how long he was in the bushes he couldn’t be sure. Up ahead the road curved next to a ravine and he could make out a figure on the sidewalk coming toward him, the curves of a woman wrapped in fleece. Donna, it would be Donna. Please let it be Donna. Closer he could see a hat and gloves and reflective tape that shone bright slashes of yellow whenever a car passed. His skin was stiff as cardboard, a jumble of invisible bones and connective tissue under age-old overalls. But there was something off in the woman’s gait; she was pigeon-toed in a way that was unfamiliar and she bounced too much on the balls of her feet. This was not Donna. Just another woman out for a night jog. Still he approached, slowing now, only wanting to lie down. The woman sped up as she rounded the corner. She had seen him maybe, done the same kind of guessing about the figure moving closer in the night, starting to emerge like a photograph in a developing tray, the lines and contours finally gaining clarity. Her bouncy strides slowed and then stopped. Invisiman shuffled through the snow. He could see her eyes. Crow’s feet dimpled her skin as she squinted, then her eyes opened full so he could see the whites. Hello, he said, but his mouth was frozen, a tin man’s jaw rusted shut. It came out garbled, like his tongue had been cut out. She came closer, her head shifted, looking at him up and down but never at his face. She was close enough that he could smell her sweaty woolen hat. He reached, his invisible cudgel arms trying to find another body, and his wrists hit her shoulders. If he could just hold her for a while. Something warm. He tried to pull her in but she pivoted in his arms and tried to run. She slipped, and when he dove and caught her ankles her body landed on the snow like a felled tree. She called out, kicked at his invisible face. Hold on, he said. Please. Just give me some time to explain.