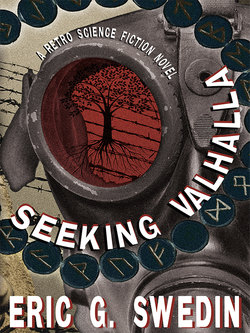

Читать книгу Seeking Valhalla - Eric G. Swedin - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TWO

The Bavarian forest in the full bloom of spring could not erase Dachau from his mind—nothing ever would. One does not forget a train full of corpses stacked like firewood or the haunted looks in the eyes of tens of thousands of prisoners, some so far gone that they couldn’t even feel grateful at their liberation. One does not forget the sight of a man lying on the ground where he fell, his chest heaving as he sucked in air, his eyes vacant.

The light-colored trunks of beech and the grey bark of oak flashed by as Napier drove the jeep along the paved road under a canopy of green. Carter sat in the passenger seat, his hand resting lightly on the .30-caliber machine gun mounted just in front of him. The girl from Ireland sat in the rear seat, a place normally filled with backpacks, duffle bags, and other gear. Napier had left those behind in a neat stack at the company’s bivouac outside the concentration camp.

Aoife spoke in English for the benefit of Napier. “I remember that small house that we just passed. The road is just up here. See it?”

As Napier slowed down, Carter looked behind them. Two trucks followed them, six-by-six Studebakers painted army green, carrying two sections of Rangers of eleven soldiers each. Carter didn’t care for acting as scout. It was bad tactics to have the command element lead, but he feared that the girl would be terrified if he and the sergeant were not with her.

A dirt road snaked off between the trees. Napier drove slower and Carter stood up to get a better look, bracing himself against the machine gun mount. Ideal place for an ambush. Besides the cover from the trees, the rolling ground made the jeep flow up and down along the road like a skiff at sea. The Third Reich might be collapsing, and her soldiers surrendering in droves, but die-hard believers still fought with skill and tenacity. Before an advance party of army soldiers had stumbled on Dachau, the Ranger company had been attached to the 45th Infantry Division, moving in position into attack Munich. That city had not surrendered, and these woods could be crawling with stragglers, deserters, and small units still under discipline.

“Please stop,” Aoife said, laying her hand on Napier’s arm.

The sergeant rolled the jeep to a stop. “What’s wrong?” he asked.

“The temple is just beyond that rise. I don’t want to see it again.”

“Fair enough,” Carter said. “Turn off the jeep, Sergeant.”

The major leaped down from the jeep and signaled back to the truck driver behind, twisting his thumb and forefinger to indicate turning off the truck engine, and twirling his finger to order the troops to dismount. Soldiers in green piled out, automatically spreading out into the surrounding trees, veteran instincts demanding that they secure the area.

“Miss McLaughlan, I’m going to leave a soldier with you and take the rest of my men forward.”

“I volunteer, sir,” Napier said quickly.

Carter looked at his sergeant. The soldier looked away, a pink flush working its way across his cheeks. Normally Carter wanted the former coal-miner from Utah to be with him at all times. The sergeant was his rock, as close to him as his younger brother back home in Virginia, always reliable, and had saved his life twice, once on D-Day and once in a snowy town in Belgium that Carter could not remember the name of. He decided that the sergeant had earned some leeway and nodded curtly.

“Corporal Finney,” Carter called to one of his section leaders. “You will take two men and scout ahead.”

The young man from New Jersey waved a salute and headed forward with two men in line behind him. Carter arranged for the two sections to advance through the woods, keeping off the road. At least it was spring, with only occasional patches of snow to be found in shaded spots.

Taking his M2 carbine from the jeep, Carter walked up along the edge of the road. Small purple and white flowers grew in clumps next to the dirt ruts, like little presents from the spirits of the forest, and Carter took care to not step on them. It just seemed wrong that anything so pretty should be destroyed. As he topped the rise, he looked back to see Napier engaged in earnest conversation with the girl.

In front of him was a small hollow. The trees had been cut back to make room for a walled enclosure. Stone pillars reached up about fifteen feet, with wooden palisades between the pillars. The corporal and the two scouts stood before a gate—not entering, just looking. Another road joined the first, just before the gate; from the wear on the ground, it looked like it was used as much as the other. Carter followed the second road back with his eyes and saw that it disappeared into a thicket of spruce, heading west. Carter sniffed the air: no smoke or any smells out of place. Some birds twittered in a nearby tree. It all seemed peaceful and safe.

Carter trotted down to join his men. The grass growing between the walls and the forest had been cut so that it was only a couple of inches high, like the lawn that Carter had played on as a child back home.

As he drew closer, he noticed that the wood forming the palisade had geometric shapes inscribed on it, and the gate itself was inlaid with a carving of an elaborate tree. Carter had specialized in Greek and Roman classics, but two classes from Professor Lundgren on Nordic languages had intrigued him enough to enable him to remember much of the content. His mind shifted gears, dusting off old information and finding fresh meaning in what his eyes saw. The geometric shapes were obviously Nordic runes. He didn’t remember what the shapes meant; his talents ran more to the auditory side of languages. The tree on the gate was obviously Yggdrasil, a giant ash called the World Tree, with a small deer at the base nibbling at its branches. This tree connected all nine worlds of Norse cosmology, from the abode of the gods in Asgard to the middle realm of Midgard where humans lived, down to Niflheim, the cold land of mists and ice, where Hel, the daughter of Loki and the giantess Angrboda, ruled.

“Shall I open it, sir?” the corporal asked. Finney had already been a sergeant twice. He was a reliable man on the battlefield, but a drunk on leave, which had cost him his rank both times.

Carter looked back and saw that his troops were approaching, maintaining their distance from each other, not clumping up like amateurs. “Second section, reconnoiter the surrounding woods,” Carter called out. “First section, follow us in.”

Finney hauled at the ring set to the side of the gate, leaning back to take the weight of what must have been a full ton of wood. He fell as the gate opened smoothly on oiled hinges. Perfectly balanced, Carter thought, as he stepped back to let the gate drift open. Good German engineering.

The wall enclosed about four acres—a garden with trimmed grass, groomed walkways of white gravel, manicured bushes, and oak and beech trees to give shade. Someone had been taking care of the place, perhaps even that morning. From the inside it was obvious that the walls formed the shape of an octagon, with eight stone towers. Stone pillars, covered with runes, some as tall as a man, were scattered about, seemingly at random, yet Carter suspected there was order to their placements. Dominating the center of the space was a giant oak tree, reaching some forty feet into the air, with a base ten feet wide, and thick branches standing firm under the weight of lush foliage.

The men scattered to explore the small buildings built against the inner walls, some of dressed stone, others of carved wood. Carter was drawn to the giant oak. He was reminded of Irminsul, meaning “great pillar” in the Old Saxon tongue, a precursor to modern German. Irminsul was a great tree that represented the connection between heaven and earth, a center of worship for the Saxons who lived in Germany in ancient times. Charlemagne, in his campaigns against the Saxons and the Danes, captured the temple and burned the tree. He intended to destroy the old pagan religions.

As he drew closer, Carter saw iron rings hanging from hooks driven into the tree about eight feet above the ground. The tree bark underneath the rings was patchy and discolored with dark splotches. In a small shrine nearby he found human skulls arranged on shelves. In a flash, it all came together. The virgins from Dachau being brought her, tied to the rings, scraping the bark off the tree with frantic motions, sacrificed, and their skulls kept as trophies, or perhaps offerings. The whole idea left him feeling sad; so much of the rage he would have liked to feel had been exhausted by the morning at the concentration camp.

A screech from a bird jerked his eyes upward. Two ravens burst from the giant tree and circled around, screaming their displeasure. The dark birds alighted on one of the stone towers and perched there, intently watching the American soldiers. A chill went through Carter as he recalled the ravens of Odin, Huginn and Muninn, meaning “Thought” and “Memory,” who traveled the world, acting as spies for the Norse god.

“Sir,” one of the soldiers called from a nearby building. “You’ve got to see this.”

Carter shook himself, making his whole body move, as if this would slough off the malaise that he felt. He trotted over to the building. It was narrow in depth, with wide doors that the soldier had pulled open. Arranged on shelves were silver bowls, steel knives, and small boxes of gold coins. The bowls were of exquisite manufacture, with runes and stylized Nordic faces embossed on them.

The soldier’s eyes gleamed. “Can we liberate some of these, sir?”

Carter allowed himself a small smile. A roundabout way to ask if looting was allowed. While Carter found looting to be unseemly, not the act of a gentleman, he knew that many of his soldiers took pilfering as their due as conquerors, as it had been for millennia.

“I recommend that you don’t,” Carter said. “This a cursed area, and these are cursed items. They will only bring bad luck. Over there, women were murdered by the Nazis as human sacrifices to pagan gods.”

The soldier’s eyes went wide as he pushed the doors closed. Carter was surprised with himself at the words that had burst out. Brought up as a Methodist and now a deist, he was not a superstitious man given to believing in rabbit-foot charms, or any of the little rituals that many of his soldiers clung to. But confronting the evidence of such raw evil made a man think in a more primitive way, of spirits and curses, of basic emotions and fundamental values.

The doors of the building held a wonderful wooden cutting of the great serpent Jormungand, who encircled all of Midgard, with his head eating his tail. Inside the serpent was a map of Europe. A great swastika showed the location of Germany. He was intrigued to find three more smaller swastikas, one in Poland, another in Austria, and still another further north in Sweden. Another great swastika, as large as the one in Germany, was located at the very top, near the North Pole. In the Holy Land, the British colony of Palestine, a cross lay broken.

Glorious music suddenly poured from the trees. Carter dropped to a crouch, looking around like a trapped animal, his carbine at the ready. He looked up at a nearby tree and saw a speaker, painted in camouflage brown, nestled in the branches. There were speakers in other trees and in recessed cavities inside the buildings. A sound expert had laid everything out so that the grove vibrated with the music. It was Wagner; Ride of the Valkyries, if he wasn’t mistaken, certainly something from the Ring Cycle. He had heard that Wagner was Hitler’s favorite composer. The Ring was based on ancient epic pagan stories, so it all made sense.

“Captain—I mean, Major,” a soldier called out. Carter had only been promoted a couple of weeks earlier, and not everyone was used to the new rank. Carter himself wasn’t used to it. Normally a captain commanded a company, so he was supposed to move up to battalion staff, but he had asked to remain with his company. The war against the Germans would only last a few more weeks at most, and he wanted to finish the war with his men; he would submit to staff work when they were transferred to the Pacific for the invasion of Japan.

Carter walked over to the soldier and was shown the interior of another of the buildings that huddled up against the temple wall. Two phonographs sat on a table, with one rotating the record on top. More records were arranged vertically in shelves, and underneath the table was a stack of car batteries connected together.

“No Tommy Dorsey, sir,” the soldier said, leafing through a sheaf of records. “Just more like this lady screaming music.”

“That’s called classical music, Jenkins,” Carter said. “Let’s turn it off. We’re still in a war and that’s like a foghorn attracting the enemy.”

Jenkins picked up the phonograph arm; the sudden silence felt eerie. Carter slowly rotated, observing his soldiers rummaging through the buildings. The ravens still watched them. There were a lot of valuable goods here and this temple had obviously been important to high-ranking Nazis.

So where were the guards?