Читать книгу Building Home - Eric John Abrahamson - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

LIKE MOST AMERICANS THAT SUNDAY AFTERNOON, the three men at the Shoreham Hotel in Washington, D.C., were surprised and dismayed by the news. Crackling through the speakers and interrupting the music, the announcer proclaimed: “. . . Japanese planes have attacked the U.S. naval base in Hawaii . . .” Without much elaboration or detail, the station returned to its regular Sunday afternoon broadcast.

With cigarette smoke drifting among them, the suntanned and ruddy-faced California executives discussed what the news would mean to their businesses and their lives. They were on their way home from the annual convention of the U.S. Savings and Loan League in Coral Gables, Florida. At the convention, rumors had circulated that the federal government was planning to impose restrictions on the use of building materials in anticipation of war.1 Restrictions would slow construction and diminish the demand for home loans, the bread and butter of the savings and loan business. Already, the government was beginning to build its own housing in Los Angeles for war workers. Many of the men at the convention chafed at these rumors, which seemed to signal a resurgence of what some described as the Roosevelt administration's command-and-control approach to the national economy.

As the men talked, their conversation reflected the national mood. Caught up in the development of their own businesses and personal lives, they blamed diplomats and politicians for failing to keep the peace. If the country had to be dragged into the conflict, they hoped it would be short-lived. A guest column written by an American admiral in that morning's Washington Post had asserted that if war broke out, the United States and its allies would quickly blockade Japan and isolate the island nation.2 Others were not so confident. Japan's alliance with Germany made the threat of prolonged war real. With the attack on Pearl Harbor, Californians, who had imagined themselves safe in their domestic tranquillity and far from the conflict in Europe, suddenly felt vulnerable.

Charlie Fletcher, a tall, broad-shouldered man just shy of his fortieth birthday, was the oldest and had the most intimate knowledge of politics. His father, an enormously successful real estate developer, represented San Diego in the California State Senate. A Progressive Republican when he was first elected, Fletcher senior had defected to the Democratic Party during the Roosevelt years. Unlike his father, Charlie remained a hard-core chamber of commerce, Herbert Hoover Republican. As an undergraduate at Hoover's alma mater, Stanford University, Fletcher captained the water polo team to a national championship. He was a three-time All-American swimmer.3 He did graduate work at Oxford and traveled through Europe, the Middle East, and Asia before returning to San Diego. In 1926, he married Jeannette Toberman, daughter of one of Hollywood's founders.4 In 1934, seizing an entrepreneurial opportunity created by Congress to promote home ownership in America, Fletcher founded Home Federal Savings and Loan. It was the worst year of the Great Depression. Seven years later, Home Federal had barely $4 million in assets, but Charlie had the resources to be patient. He remained confident and optimistic.5 Cool-headed and cautious by nature, he resisted the war fever brought on by the bombing of Pearl Harbor. With a wife and young children, as he told his companions that afternoon, he had no intention of being dragged off to fight. He would sell war bonds instead “so the other guys would have something to fight with.”6

Howard Edgerton, or “Edgie” as his friends called him, provided a stark contrast to Fletcher's cautiousness. Born in Sulphur Springs, Arkansas, in 1908 and raised in Prescott, Arizona, and Los Angeles, the thirty-three-year-old Edgerton was a glad-handing westerner. At five feet ten inches tall, he had a muscular but trim build. He graduated from the University of Southern California in 1928, stayed on to earn a law degree in 1930, and then joined the Railway Mutual Building and Loan Association.7 Within five years he had taken over management of the organization, converted it from a state to a federal charter, and changed its name to California Federal Savings and Loan. He became president and CEO in 1939.8 By 1941, his company had assets of approximately $5 million. Financially, he was comfortable enough to be the part owner of an airplane but he was not rich.9 Unlike Fletcher, Edgerton was eager to go to war. Facetiously he announced he “was all set to be a general.”10

Howard F. Ahmanson was undoubtedly amused by the discussion between his two friends. A handsome thirty-seven-year-old man with deep blue eyes that “just looked right through you,” he could be charming “and make you feel like you were the center of the world.”11 When angry, he was often imperious and caustic. An Omaha native, Ahmanson moved to California at the age of nineteen, studied business at USC, and made his first million dollars in the middle of the Depression by selling insurance. Living in a fine house in Beverly Hills, he and his wife, Dorothy “Dottie” Johnston Grannis, had been married eight years but had no children. By nature, he was not impulsive. He worried over business problems but understood the profit to be made by taking calculated risks. Savings and loan executives like Fletcher and Edgerton who steered customers to his insurance company were crucial to his success. They were also among his closest friends.

Ahmanson was cautious about the war. He had seen the rise of militarism in Germany and Japan firsthand. He and Dottie had traveled extensively in Europe during the summer of 1938, shortly after Hitler's annexation of Austria. Two years later, they had sailed to Japan.12 At the time, the Japanese army was ruthlessly suppressing resistance in conquered territories in China and Southeast Asia. Though just a tourist, Ahmanson had observed it all. Now, with war assured, he insisted that, like Fletcher, he would have nothing to do with “this flag-waving uniform business.” If the government wanted him, they would have to come and get him.13

As speculation and rumor fed the conversations at the Shoreham that afternoon, the rumble of taxis and the slamming of car doors could be heard from the lobby. Some of the hotel's permanent residents, including senators and congressmen, rushed off to the Capitol and the White House. That night, President Roosevelt met with congressional leaders from both parties. Bitter party rivalries dissolved in the face of the Japanese attack. As these leaders returned to the hotel in the small hours of the night, word spread that the president would ask for a declaration of war.

Fletcher and Ahmanson may have begun to change their minds about their own involvement in the war the next morning. Edgerton, and perhaps the other two, joined the crowds outside the Capitol plaza as police and Secret Service agents kept access clear. From the packed and tense galleries of the U.S. House of Representatives, Edgerton watched as the president, accompanied by his son, a marine lieutenant in uniform, lifted himself to the microphone-cluttered rostrum.

On a date “which will live in infamy,” the president began, his words crackling through the speakers of millions of radios across the country, “the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.”14 The surprise offensive had included assaults on the Philippines, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Guam, Wake Island, and Midway. “No matter how long it may take us to overcome this premeditated invasion,” Roosevelt said, “the American people will in their righteous might win through to absolute victory.” Members of Congress and the audience rose to applaud. Within an hour, both houses of Congress, by a nearly unanimous vote, approved the declaration of war.15

The Japanese attack unified the nation in anger and accelerated the militarization of the economy. Ford, General Motors, and other automobile companies began turning out Jeeps and tanks. Kaiser, Bechtel, and other heavy construction contractors in California started building Liberty ships and military bases. Food processors like Del Monte and S&W Fine Foods began canning California peaches, cherries, and grapes for mess halls in Europe and the Pacific. In Southern California, Douglas Aircraft scrambled to increase their production of bombers. Indeed, Southern California and its economy would be permanently transformed by the war.

Across the country, men and women lined up outside military recruiting offices to volunteer. Many who didn't were drafted. Fletcher and Ahmanson eventually joined Edgerton in the armed forces. None of the three saw combat, but the war years crystallized for them a complicated perspective on the relationship between citizen and country, private endeavor and public service, that would shape their entrepreneurial lives and the social contract between American society and business for a generation. Their wartime experiences would also give them powerful insights into the growing military-industrial complex and its influence on the future of Southern California.

The war reshaped the country's culture. When it was over, the devastation in Europe and Asia ensured that American industries would face limited competition from foreign manufacturers. With a domestic market primed with wartime savings and shortages, consumption skyrocketed as American workers enjoyed an era of unprecedented prosperity. Government policies, especially the GI Bill, recognized the service of veterans and sought to ensure a smooth transition to a peacetime economy. The GI Bill promoted education and training, entrepreneurship, and—most important for Fletcher, Edgerton, and Ahmanson—home ownership.

In this postwar era, all three men would be enormously successful in the savings and loan industry and would contribute substantially to the growth of Southern California. They played a significant role in the region's politics and cultural development. Among them, however, Howard Ahmanson would prosper beyond all imagining, building the largest savings and loan in America and enabling millions of Californians to realize the American dream.

SUCCESS IN A MANAGED ECONOMY

Ahmanson made his fortune in the context of an industry and an economy that became highly managed by government in response to the Great Depression and World War II. In the managed economy, government harnessed the capacities of private enterprise to achieve social goals. In turn, private enterprise maximized its profits by using government to stabilize competitive markets.16

Financial services were at the center of the managed economy. Under this regime, commercial banks and savings and loans enjoyed limits on competition and received government protection from catastrophic risk. Regulation, fiscal policy, and the monetary initiatives of the Federal Reserve were the most important tools the government employed to protect the financial system from collapsing and to provide an economic safety net—and eventually the means to attain a piece of the American dream—for as many citizens as possible. In return, the government expected the banking system to provide a stable supply of credit and an efficient system to channel the nation's savings into investments.

The mortgage industry and home ownership grew tremendously in the era of the managed economy. Government loan guarantees and mortgage insurance provided by the Veterans Administration and the Federal Housing Administration lowered lenders’ risk. With less risk, lenders could afford to make loans at affordable interest rates to younger borrowers with less savings and lower incomes.17 New home construction exploded. By the end of the 1950s, a quarter of the nation's single-family homes were less than ten years old. Middle-class savers provided much of the capital to finance the mortgage market with their life insurance premium payments as well as their savings accounts, and their companies provided more with their pension fund investments.

Among all the institutions shaped by the managed economy, the savings and loans—or thrifts—were especially important for economic, cultural, and political reasons. They represented the blended ambitions of businessmen, regulators, and politicians. Regulators wanted to rationalize the financial system to create stability in the marketplace. Politicians saw in thrifts a return to cultural ambitions rooted deep in the Jeffersonian ideal. By extending the opportunity of home ownership to a majority of the nation's households, Congress and various presidents sought to reaffirm the roots of an independent citizenry in the rich tradition of property ownership. Although leaders in the savings and loan industry—including Ahmanson, Fletcher, and Edgerton—shared this belief in the social value of home ownership, they also saw the entrepreneurial opportunity that the American dream created and appreciated how government intervention limited their business risks.

During the era of the managed economy, entrepreneurs like Howard Ahmanson in industries ranging from communications to transportation to financial services succeeded because they understood the social contract between business and government. They took advantage of competitive opportunities, subsidies, or protections created by government. They artfully managed their relations with politicians and regulators to protect their state-created advantages and opportunities. At the same time, they deployed traditional entrepreneurial skills to create products, services, and organizations that fit the markets circumscribed by policy makers.18

Howard Ahmanson reflected many of the characteristics of the government entrepreneur in the era of the managed economy. After purchasing Home Building and Loan in 1947 (later renamed Home Savings and Loan and then just Home Savings), he understood and embraced the government's policy goals, particularly the central effort to promote home ownership. He cultivated relationships with legislators and regulators to protect the policy-driven business environment that made him and his companies successful. He invested part of his profits back into the community to reinforce the civic qualities of his entrepreneurial endeavors.

SHAPING POSTWAR LOS ANGELES

The success of Home Savings reflected the remarkable achievements of the savings and loan industry in Southern California. During the era of the managed economy, when savings and loans made the majority of loans to home owners throughout the country, thrifts in Southern California dominated the mortgage market far more than they did in any other region.19

The extraordinary success of the savings and loan industry in Los Angeles was anchored in a number of factors: the city's explosive growth in the postwar era, the underlying opportunities created by government programs for returning GIs and middle-income families, and a cadre of industry leaders who capitalized on these opportunities to propel their businesses. Through its real estate development entities and its lending practices, Home Savings and Loan and other thrifts in Southern California played a leading role in the postwar suburban explosion that made Los Angeles the quintessential postmodern city.

With their personal fortunes and egos so intertwined with the city's development, it's not surprising that Ahmanson, Edgerton, and other savings and loan executives exerted an important influence on the cultural development of Los Angeles as well. Through the unique art and architecture of its branches, Home Savings and Loan reflected a specifically Southern California perspective on the American dream. Through his philanthropy, Howard Ahmanson contributed to Los Angeles's transformation from a cultural backwater to a world-class city for the arts.

THE END OF THE MANAGED ECONOMY AND THE CONSENSUS SOCIETY

From the Great Depression to the Great Society, a majority of the nation's citizens and its leaders believed in government's efficacy and the idea of the managed economy. In 1964, for example, three out of four Americans agreed that the government would “do what's right” always or most of the time. Nearly two-thirds (64 percent) said that the government was run for the benefit of all. As the memory of the radio broadcast on December 7, 1941, faded, however, public trust and confidence in government declined dramatically. Civil rights and antiwar demonstrations in the mid-1960s reflected growing social unrest. Two years after Howard Ahmanson's death in 1968, barely half of the country was confident that the government would do the right thing and six out of ten people believed that the government primarily benefited special interests.20

The decline in public confidence in government was mirrored by a growing intellectual attack on the idea of the managed economy. Economists at the University of Chicago and other institutions highlighted inefficiencies in the regulatory system. These theorists, along with consumer advocates, charged that regulators were too often “captured” by the industries they were supposed to regulate.21 As a result, these agencies reached decisions outside of the core democratic framework embedded in the Constitution.22 Meanwhile, business leaders chafed at rules that prevented them from pursuing opportunities tied to their core assets or skill sets. Their voices added to a rising tide of popular antigovernment sentiment as the consensus forged by the war years faded in the nation's collective memory. In this political economy, a sweeping movement toward deregulation, or what one scholar has called “contrived competition,” reshaped the landscape of many industries, including mortgage lending and financial services.23

The high tide of the deregulatory movement came in the late 1990s with the repeal of major elements of financial regulation that had been the centerpiece of New Deal reforms in the 1930s. Massive consolidation in financial services followed, with commercial and investment banks merging with insurance companies and brokerage firms. In 1998, long after Ahmanson's death, Home Savings was sold to Washington Mutual, and the combined entity instantly became one of the largest banks in the country. Washington Mutual's success in this new environment was short-lived. When the housing bubble burst in 2007, the value of mortgage-backed securities plunged. Weakened by these collapsing asset values, in 2008 the company was acquired by JPMorgan Chase in a fire sale that brought a sad end to an institution that had once epitomized Southern California success and stability in the era of the managed economy.

The collapse of Washington Mutual and the mortgage market challenged fundamental elements of both the managed economy and deregulation. Conservatives blamed policy makers, insisting that the drive to extend home ownership to more and more lower-income Americans had gone beyond the bounds of prudence and reason.24 Others suggested that elaborate new strategies for risk analysis had encouraged overconfidence on Wall Street.25 Demand for mortgage-backed securities grew so large that it led to dramatic declines in credit standards as lenders practically threw money at borrowers, knowing that mortgages could be quickly securitized and sold to investors. Much of this problem could be tied to the transformation of mortgage lending brought on by securitization and deregulation. As finger-pointing began and calls for a new regulatory framework in financial services grew, the history of the managed economy and the mortgage market in the postwar era seemed strangely forgotten.26

OVERVIEW

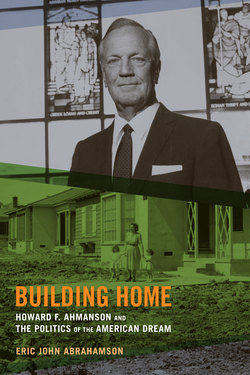

In the context of the mortgage market's collapse and of widespread disenchantment with the pattern of deregulation over the past three decades, this book offers a look back at a different era. It weaves together three stories. It is one part corporate and industrial history, using the evolution of mortgage finance as a way to understand larger dynamics in the nation's political economy. It is another part urban history, since the extraordinary success of the savings and loan business in Los Angeles reflects the cultural and economic history of Southern California. Finally, it is a personal story, a biography of one of the nation's most successful entrepreneurs of the managed economy—Howard Fieldstad Ahmanson.

Unlike tycoons of an earlier era, Ahmanson evidenced neither inventive genius nor the ability or desire to oversee a great technological enterprise. He did not control some vast infrastructure like a railroad or an electrical utility. Nor did he build his wealth by pulling the financial levers that made possible these great corporate endeavors. Instead, he made a fortune by financing the middle-class American dream.

Perceived as a risk taker by outside observers, Ahmanson was actually extremely careful. He studied problems—in business and on the high seas—and devoted himself to limiting risk. In his initial field of endeavor, insurance, he found the safest of all markets and profited by minimizing losses. In lending, he focused exclusively on single-family homes, believing that the American dream of home ownership was so powerful that it offered the lender an extra margin of safety. In a racist era when even the federal government officially countenanced segregation, he avoided neighborhoods of color, preferring to lend to the aspiring white, middle-class home buyers that he knew and understood.27 He succeeded by sticking to the basics as he understood them: sound lending, low-cost operations, and economies of scope and scale.

In an era famous for faceless corporate control and organization men, Ahmanson evidenced numerous contradictions. He refused to sell stock in his various companies, maintaining total personal control. Yet he was also a delegator—assembling a close circle of lieutenants who managed the company's day-to-day operations according to his vision so that he could work from home and take a dip in the pool whenever he felt like it. Though he clearly wanted the limelight, he was reluctant to be inconvenienced by public attention. Despite owning the largest and most successful savings and loan in the country, he had little to do with his industry's trade associations. With his great wealth, he contributed substantially to the expansion of the cultural institutions in Los Angeles and was pleased to have galleries, theaters, and research facilities named for him and his family. But after a brief flirtation with politics in the mid-1950s, he let others manage his company's lobbying and political deal making and deemed party politics a waste of time.

Yet Ahmanson was hardly a recluse. From the 1930s on, he and Dottie appeared regularly in the society pages of the Los Angeles Times. With a drink and a cigarette in front of him, he played the piano or the organ for his fellow revelers. After he and Dottie separated in 1961, his friend Art Linkletter, the television show host, introduced him to Caroline Leonetti, a charm school entrepreneur and TV personality. Smitten by her energy, intelligence, and good looks, Ahmanson married her. Together they hosted the power elite and helped to build cultural and educational institutions that he hoped would begin a new era in the history of Los Angeles and Southern California.

On his boats and in his business, Ahmanson brooked no dead weight and demanded loyalty, integrity, intelligence, and hard work. He also was ferociously competitive. He and his crews won most of the major West Coast yachting races in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Some of his closest friends were business rivals. He could enjoy their companionship and yet take great pleasure in beating them on the ocean or in the marketplace.

Despite his high standing among the nation's wealthiest citizens and the headlines that he and his yachting crews made in the Los Angeles Times’s sports section, most Americans and even Southern Californians knew little about Howard Ahmanson. In the infrequent profiles that appeared in the press during his lifetime, Ahmanson mythologized his childhood, repeating the same stories from one interview to the next. The uneven paper trail he left survives because others, particularly his first wife, Dottie, kept some of his personal correspondence. Only a few of his close relatives, friends, competitors, and business associates remain to tell his story. Yet when the fragments of his life are fitted into the context of his times, his biography sheds light on an important era in America.