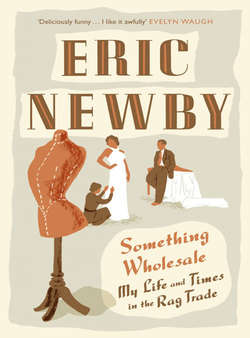

Читать книгу Something Wholesale - Eric Newby - Страница 5

Preface

ОглавлениеThe hero of this book, if it has one, is the man who, during the years it describes, was head of the dressmaking firm of Lane and Newby – in other words my father. But this was my father in old age. We were separated by a great gulf of years, and when I was old enough to appreciate him the world which he knew and of which he was a part had passed away.

What do I know of my father as a young man? Practically nothing. His father came from the East Riding of Yorkshire and he acquired a stepmother at an early age. I know that with her his life was not very happy. It was one of the few things that when he spoke of it moved him to tears.

I look at photographs of him in our family albums taken when he was twenty or so – great group photographs of men and girls upriver, perhaps, after an outing or a regatta – and wonder what he and his companions were really like. He was very handsome, this is obvious – with a fine, well-tended moustache – and he was elegant, either in a negligent manner with a silk handkerchief knotted round his neck and a panama hat with the brim turned up in the front or else more formally in a dark suit with a watch chain and a straw hat with a black band.

The girls are dressed to the nines with fichus of lace and hats like great presentation baskets of fruit from Fortnums.

They must be upriver. In the background of the particular picture of which I am thinking there is a white clap-boarded house. It is probably a club-house or it might be a mill and beyond it the woods are thick and green, like the Quarry Woods at Marlow, only the house is not at Marlow.

Where is it? I wish I knew. There is no one left to ask. Perhaps, somewhere, one or two of those young men and women are left alive, but they would be very old now.

Some of the girls must have been beautiful but one must make an effort of will to believe it. Their clothes makes them seem older than they really were. And the way in which the photographer took his pictures endows them with too much chin, or else no chin at all. They look absurdly young or else like maiden aunts. The effort of keeping still for the photographer on that warm summer’s day and looking into the sun was too much for them, particularly for the men. Some of them are squinting, some are out of focus, some have an air of being slightly insane. It is gratifying to see that in all these groups my father took the precaution of seating himself next to the most good-looking girl available. I would like to know how they spoke, these friends of my father; the idioms they used; the things that made them laugh; but I shall never know, more’s the pity and neither will my children.

There are more rural scenes. Photographs taken not by a professional but by one of my father’s companions when they were camping, in the doorway of a tent, early in the morning with the mist still rising from the meadows. They look dishevelled, as if none of them had slept well, perhaps there were horses in the field. One of them is smoking a meerschaum pipe with a Turk’s head carved on it. In the foreground there is a large black cooking pot, suspended from a metal tripod, simmering over a wood fire. All the cooking equipment is tremendously heavy. How did they get it there? They must have used a horse-drawn vehicle. It is a pity that there is no picture of it.

There is a series of photographs taken off the East Coast in a yacht with a hired man. ‘He was a real old salt,’ my father told me. In these pictures he and his friends are all wearing black and white striped trousers rolled up to the knees and stockinette caps. In the background of one of them there is a light-ship and close to it a barquentine, deep-loaded, running before the wind. Whoever took the photograph had difficulty with it because the horizon goes rapidly downhill! ‘There was a bit of a lop on,’ my father said, wistfully. He had always wanted to be a sailor. And when his father married again he tried to run away to sea but was brought back in a cab. Next in time are the photographs of my mother taken the year before I was born, looking gentle and rather sad, and another of my father looking severe and bristly reclining on a velvet cushion up in the bows of his skiff. I wonder how things went that day. Was she having sculling lessons at that time? Perhaps she wasn’t getting her hands away properly.

The next photographs are of my father partially domesticated, taken on the beach at Frinton. I am on the scene now, large and shiny in a large, shiny pram. I look like an advertisement for some health food. I think my father has just arrived from London on the afternoon train. He is dressed for London. Looking at the photograph now I almost convince myself that I remember the moment when it was taken. But who took it? I seem to remember a nurse with starched cuffs and dark rings under her eyes who used to have assignations with old men in the local cemetery when she was supposed to be giving me an airing, and was summarily fired for it. Perhaps she took the picture.

There are pictures on Sark. I am sitting on my father’s head as he wades through the bracken. It was an enchanting spot in the Twenties. There are a lot of photographs of the Twenties. My mother in a cloche hat at Deauville. Scenes at Branscombe in Devonshire of two sisters, both store buyers, Lolly and Polly, friends of my parents, identical in long jerseys and strings of beads, surrounded by a whole pack of Pekinese.

Lolly was the best suit buyer in London. She was extremely good-hearted but could be extremely autocratic. On one occasion a customer had a suit on approval and, thinking that she would not be detected, wore it at the Royal Military Meeting at Sandown Park, where she was seen by Lolly, who was mad about racing.

On the following Monday the customer returned to the store and complained that the suit which she was wearing had some imperfection in it and demanded a reduction in price.

‘If there’s something wrong with it,’ said Lolly, ‘then you shan’t bloody well have it.’

She made her take it off in a fitting-room. ‘Now bloody well go home without it!’ she said.

Eventually the customer had to buy another suit in order to leave the building, one that was even more expensive than the original, which Lolly promptly marked-down in price and appropriated to her own use, having wanted it for herself in the first place.

There is a whole gallery of memorable characters in these albums. Captain and Mrs Buckle – Mrs Buckle smoked a hundred cigarettes a day. ‘Gaspers’ she used to call them, and her voice was reduced to a hollow croak. Ivor – a young man who had an open Vauxhall with a boat-shaped body and used to drive to Devonshire in silk pyjamas after parties in London. He inherited a fortune when he was twenty-one, got through it in a year and became a bus driver. He used to wave to my mother when he drove the number nines over Hammersmith Bridge. And there is another buyer called Phyll – who lived in sin with someone called Uncle Fred, who wasn’t an uncle. At Christmas time Auntie Phyll’s flat resembled a robber’s cave with presents from manufacturers piled high in it. Those were days when a fashion buyer was expected to feather her nest (nobody else was going to do it for her) and many a buyer was able to retire to a riverside cottage on the proceeds of the toll she exacted from the manufacturers on every dress that went into her department. On one occasion a disgruntled manufacturer informed the management that Auntie Phyll was taking a percentage in this way but was nonplussed when he was told by the Managing Director that they didn’t care what bribes she received providing that the clothes she bought were as well chosen and as cheap as those of their competitors.

And there is a whole supporting cast of rural characters from the village where we had taken a cottage for the summer. Photographs of the innkeeper, who was having a violent affair with the barmaid under the nose of his wife; photographs of his wife and the barmaid, who looks very innocent in a velvet dress, and pictures of village children with whom I used to float paper boats down an open sewer; and the policeman’s son who taught me to say bloody. Once for a bet I drank the water from the sewer. The results were not what normal medical experience would lead one to expect. Instead of contracting dysentery I had a complete stoppage of the bowels that lasted for more than a week.

And there is the last photograph I have of my father. He is sitting with my mother in an umpire’s launch on the river at Hammersmith. It is the summer of the year he died. He has shrunk with the years, but with his white club cap he looks for all the world like a mischievous schoolboy.