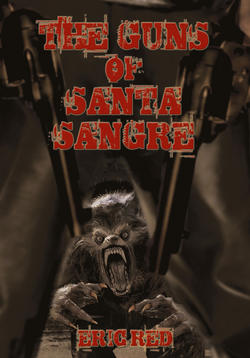

Читать книгу The Guns of Santa Sangre - Eric Red - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER THREE

The one called Tucker leaned back in the chair, put his dusty boots up, spurs clinking, and squinted out at the harsh Durango desert that lay beyond the porch of the rundown cantina. One big empty. The sun was just rising, already blinding, and he dipped his hat brim to shadow his face. It was going to be another hot damn day. The man was tall and lean, the shag of beard bare by the scar on his jaw but thick across the rest of his sunburned leathery face. He rolled a cigarette and lit it between thick fingers, with cauliflower knuckles broken several times on others’ faces, and sucked in the good hurt of the bad tobacco. His Colts hung heavy in his holsters. Flies buzzed in the air.

He didn’t like the way the peasant was staring at him.

The Mexican had been there for an hour standing across the street, sizing him up. Usually these villagers kept their distance, keeping their eyes and heads down, avoiding trouble, but this little brown man had been looking at him with interest for a while now. Maybe they didn’t get too many gunfighters around here, the bunghole of the earth.

Slapping an annoying fly on his cheek stubble, the gunfighter wiped the crushed insect off his palm on the wooden post, settling back in his chair with a creak of leather as he shifted his boots.

The dismal outpost was nestled in the desert flats one hundred twenty miles from Villahidalgo for travelers passing through on the Santa Maria Del Oro trail. It wasn’t much, just a cantina, feed store, barn and a ramshackle corral. Tucker had his horse tethered there along with those his compatriots rode. The gunfighter had been here a week, lying low with the other two, planning their next move. He wondered how the hell he’d ended up here. The only other human beings he’d seen were the occasional Mexican farmers who rode through to purchase supplies for the few poor scattered villages throughout the area. None of the peasants had given him so much as a passing glance.

Until this one.

The brown man stood across the street from the cowboy, watching him sitting on the porch smoking his cigarette.

And this way they killed a few more minutes.

It was just a harmless peasant, Tucker decided, who didn’t appear to be armed, though he didn’t know that for sure. Unwashed wretch was covered with filth, his face smeared with caked mud, grime and sweat. The cowboy wondered if these people bathed, and this one was the dirtiest he had ever seen. By habit, the shootist gauged the possible threat this stranger might pose to him on this barren morning and how he would handle it. The peasant was alone. Impoverished as he clearly was, he may have recognized Tucker from the wanted posters and thought he would try for the reward to feed his family. He had no rifle but could possibly have a pistol under his baggy clothes. Might be he had a knife or machete there instead. If the loiterer stepped within ten feet of him, Tucker would draw his gun. The man would be dead in the dirt before he drew down. The gunfighter was fast, very very fast. That was why he’d lived to age thirty-four.

The lazy minutes passed. Tucker finished his smoke, pitched it with a flick of his fingers, and crossed his hands over his tight stomach, fingers inches from his Colt Peacemakers in the holsters slung from his chaps. The peasant didn’t move.

Squinting up the street, he saw Fix sauntering up the block in his suit and bowler hat, pistols at his sides. Thin as a rail, a black mustache on his face, beady eyes that didn’t miss a thing, the other man gave a tiny nod of acknowledgment.

“Who’s the sombrero?”

Tucker shrugged. “Been giving me the eyeball last hour.”

Fix regarded the peasant with a squinty black bullet eye. Quicker than any man Tucker knew to size up a threat, he was the fastest to dispatch it. The other cowboy was small, didn’t move much and was a man of few words, but he struck with the lethal speed of a scorpion. Fix took a chaw off a plug of tobacco and spat, squinting at the Mexican. “Looking for a handout?” he said.

“Mebbe.”

“Could be looking to get hisself the reward on us.”

“Mebbe.”

“Where the hell’s Bodie?”

“Sleepin’ it off.”

“Right.”

“Mexican’s still there.”

“Yup.”

“We’re flat broke. I got three dollar.”

“Then you’re holding all the money.”

“The hell is Bodie?”

A sound of something heavy falling, a vulgar curse and muttered grumbling answered his question. There was more banging, more cursing. Tucker and Fix turned their heads to see the third of their number, Bodie, stumbling around the side of the cantina. The Swede was a massive man, six foot five and thick as a buck and rail fence. His face was a square boulder set with sleepy, slow eyes and laugh lines around a mouth quick to smile. A lock of blond, uncombed hair fell along his face. With a broad, cracked grin, Bodie leaned against the wall beside Tucker’s chair. He tightened his cartridge belt around his waist, from which swung twin Remington Army revolvers. “Boys, my head’s comin’ apart. Right shorely it is.”

“Hair that bit ya.” Fix tossed Bodie a silver flask. Bodie took a swig.

“We need money, boys,” Tucker said, looking out at the sun lifting just above the horizon. He hated being broke, and this had been a bad spell. The gunfighter needed to make some cash quick or starve and he’d been considering their options. Most promising was a small cattle drive they’d ridden past in Juarez. Two days’ ride and Tucker, Fix and Bodie could catch up with the four wranglers, mostly kids, who wouldn’t stand in the way long of gunmen the ilk of he and his partners. They could either tie the wranglers up or shoot them, then haul the stolen cattle down to one of the many ranches near Mexico City and sell them for five bucks a head. It wouldn’t be the first time they’d resorted to thieving. He didn’t like it, but a man had to make a buck.

“Scalps is selling for a good price.” Fix used his Bowie knife blade to clean some dirt from under a fingernail.

“We don’t do that,” Tucker whispered.

“Maybe we should start.”

“I don’t trade in no hair.” Bodie shook his head in disgust.

“Me neither.”

“Well we better figure our situation out and get a plan, or we’re going to be eating sombrero over yonder.”

“Plan is saddle up. Time to move. Can’t stay around here.” Tucker grunted.

“Thought we were going to lie low until them Federales moved on.”

“They may have already done.”

“We don’t know that.”

“Point is, we just can’t sit around this hole rottin’ away forever.”

“Bodie’s right. We’re getting lead in our ass. Man’s gotta keep moving.” They were men of action and do or die they needed to saddle up.

“That peasant’s gettin’ on muh nerves. What’s he doin’, just standing there?”

The three big tough gunslingers lounged on the porch of the cantina and looked at the Mexican.

He was coming across the street toward them.

Finally, they would learn what he was after.

As he came in their direction, the peasant doffed his sombrero, kowtowed and submissive as a dog who’d been beat too much. He stopped at the edge of the porch, where the gunmen fingered their triggers. “Please, señors, may I speak to you?”

Tucker fired up another rolled cigarette and targeted the stranger with a glowering stare through the fire of the match. “What do you want?”

The humble Mexican peasant stood before them, sunburnt head bowed, holding his straw hat contritely. He was in his late teens with soft features, baggy clothes and a quiet voice. “We are poor, we have no money to pay,” he said. “They have killed our women and children. This is not the worst of it, señors. They have taken over the church. In our village, our church was Santa Tomas, but now the people call it Santa Sangre. Saint Blood. Those who have come, they drink our blood, eat our flesh, they are men that walk like wolves. Will you help us, please?”

The gunfighter Tucker looked at the other two gunslingers, spat in the dust and spun the cylinder of his revolver. “What’s in it for us?”

“Silver.”

“Thought you said you didn’t have no money.”

“It is the silver in the church. Plates. Statues. A fortune, señor.”

“It belongs to the church.”

“The church of Santa Sangre now belongs to them, señor.”

“So we kill them for you, we take the silver, that the deal?”

“You will need the silver. You will need it to kill them, señor. You must melt it down into bullets that you shoot through their hearts. It is the only way to destroy the werewolf. What silver is left after you kill them, you may keep.”

“How many?”

“Many.”

“We’ll think about it.”

“But you must leave now. Tonight is the full moon.”

Tucker studied his spurs, then looked laconically sideways at his comrades.

Bodie shrugged.

Fix clicked his teeth, which meant fine.

None of the three gunfighters bought the Mexican’s story.

Except the part that there was a church and it had silver.

If it was there, it was there for the taking.

Tucker rose to his feet and grinned down at the peasant. “Hell, we got nothing better to do today.”

Without further discussion, the shootists ambled over to the corral for their horses. The peasant fetched his own from behind the barn. They all swung into their saddles.

The four riders rode out.

The length of fabric tightly tied around her upper torso, flattening her large breasts, made her bosom itch beneath the canvas shirt. The cloth was coming loose in the up and down motion from the horse. She wished she’d tightened it back by the cantina, worried her bind would come off and concealed tits bounce, giving her away. The girl felt dirty and squalid and yearned for a bath, but the filthier she was the better. Before riding into the outpost, she smeared mud and dirt all over her face to help disguise the womanly contours of her features, and the grit was now caked with crud, but so be it. The three gunfighters did not know she was a girl. She wanted to keep it that way. These hard men must not learn her sex if she was to keep her virtue.

Her name was Pilar.

The four riders galloped across the arid Durango desert plain. They slowed the horses every few miles, then spurred them on again, pacing their animals against the brutal heat beginning to bear down. They’d need to make time now, because the horses would be exhausted and slower by the time noon hit, the sun a kiln overhead, and their progress would be impeded. It would take hours to prepare for the battle ahead and they had to reach the village by noon to be ready by nightfall.

The gunfighters’ horses were big and hers was small. It was a simple, scrawny mustang from the humble stables in her poor town, the best they had. Her small ankles kept rubbing against the ribs sticking out of her pony. The animal had not been properly broken and kept tossing its head against the bit in its mouth, but she held her reins firm in her small soft fists and maintained control of the mount. It must not throw her and run off. Her life and that of her entire village depended on Pilar getting these men there and she must not fail. She had never known such a burden or felt so alone. Again and again, as the girl rode, she prayed quietly to herself that she and her warriors would arrive in time and in one piece. God must not abandon her in their time of need.

The sound of sixteen hooves thundered across the parched desert and scrub. Pilar kept her horse in the lead, following the tracks of the trail she made riding in a few hours ago. Her ears were good. Behind her back, she heard the men talking to one another, keeping their voices low but not low enough, likely figuring she did not understand them, but she did. The Tennessee missionary who had been their village’s reverend had seen to that, teaching her how to read and speak English from childhood.

“The Mexican says it’s a three-hour ride to Santa Sangre,” the strong one was saying.

“It’s mebbe mid-morning.”

“You buy this Mexican’s story?”

“Not a word.”

“Except the silver part.”

“And we’re going to steal the whole damn thing.”

What did she expect, wondered Pilar. They were men of the world, susceptible to greed, yet something in her trusted that they would do the right thing when the time came. To come face to face with the monsters would make anyone kill them. Have patience and fortitude, she reminded herself as the saddle slapped her sore thighs; these men could not be any worse that what had come to her village.

Her only worry was them discovering she was a girl and that they would rape her before they reached town. She was a virgin, and these were dangerous men who would take her virtue if they knew, because men such as these did as such men do. But right now, her secret was safe.

“Hey, Pablo. Ain’t sangre the Mexican word for blood?” The tall, handsome one she had first observed was speaking to her.

“Si,” she called back, lowering her voice to a manly timbre.

“Why the heck you go and name your church something like that?”

“The name of our church was changed to Santa Sangre because of the terrible thing that has happened there.”

The same one she first laid eyes on in the town spoke roughly as he rode up beside her, leather chaps squeaking and spurs clinking as his knees clenched the saddle.

“Okay, Pancho. We want the whole damn story, no bullshit. What the hell is going on in your town?”

“The werewolves changed the name of our church. It is they who called it Santa Sangre, in honor of their God.”

“Start from the beginning.”

They all slowed their horses to a trot so the frothed, lathered animals could catch their breath and the men could hear. The sun now hung at nine o’clock, rising ever higher, burning like a white bullet hole in a slate sky. They had three hours to make Santa Sangre by noon.

On the long hot ride, the peasant told the gunmen her tale ...

Remember, Pilar, remember it all.

Every detail of the horror.

These men must know so they can be ready.

Oh Pilar, last month seems like a lifetime ago.

So many friends gone.

The way they died.

The town a shell.

My home, hell on earth.

I don’t want to remember, don’t want to think back and weep because only women cry and that would give myself away, but tell the tale I must, so these fearsome men believe what they are up against.

That long first night, bracing the shutters of our windows closed with both hands to keep out the howling so loud it shakes the boards under my palms, coming from everywhere, everywhere ...

The village was warm earlier that evening and everyone was on the streets as I ended the lesson and told the children to run home. The little ones are laughing. Small Pablo needs a bath. Tiny Maria is so pretty with the bow in her hair. They gather their books and get up to leave my classroom as I erase the chalkboard. The sky was red. I stepped out the door onto the dirt and smelled the dust and mesquite, straw and dung of the fine evening air. The smell of home. The road passes through the huts and corrals and my farmer neighbors in sombreros and ponchos ride by on burros and horses, their carts full of hay and sheep. I smile at my friends. The church bells ring, and I look up the hill to see the steeple of Santa Tomas watching over us.

I am almost home and listen to the coyotes yip in the desert, their familiar high-pitched, keening yelps echoing near and far, front and behind. We must bring the dogs in tonight. The coyotes stop their calling, as if frightened. It was then, one month ago today, when our town first heard the baying howls out in the mesas. How I remember the pale near full moon that hung in the skies, so huge, so white, the color of rotten milk. Out in the fields, I see two farmers my age, Manuel and Roja, tending their meager crops. They whirl at a terrible sound and look far out into the hills, eyes wide in fear. The howling was so loud it shook the ground, a cry like wolves, but bigger and much, much worse. Roja dropped his rake and rushed back to the village. Such commotion in the square. Everyone is rushing to their huts, tying off their horses, grabbing their wives and children, and hurrying inside their homes.

Yes, good, the three dangerous gunmen riding with me are listening closely now, leaning in their saddles to hear, eyes glinting with interest, and I have their attention.

Mama!

I flee home and as I run past the other huts I look through the open doors and windows being shuttered and bolted and see throughout the village the families huddled fearfully in their hearths. Over there Gabriel and Maria peer nervously out their window into the dark and empty square, and there, the frightened eyes of Jose duck down through the window of the next hut. The dogs in the town bark feverishly until the howls grow too loud and even the strongest dog cowers. When I reach my place I bolt the door and window and stay with Mama. In her eyes was a fear I’d never seen.

“Como?” I ask.

“Antiguo unos,” she whispers. “Hombres lobos.”

I had seen the pictures in the cave on the hill the ancient ones drew when the moon was young, telling the legend of the men who walked like wolves, but it was a children’s tale, and I did not believe such foolishness, so reckless was I. They had returned. Maybe they had never left.

The door and windows we shut with heavy wood and iron bolts, but we could hear, oh could we hear. The roaring outside the town tightening around us like a noose. The plates shook in the kitchen. It sounded as terrible as if they were right outside, but they were still in the hills. At last I can stand sitting still no more and must know what is out there. Over my mother’s pleas, I pry her hands from my dress and rush to the window, pulling back the bolt over the slot that my father had built just large enough to stick the snout of a gun through. I press my eye to the opening and first just see the darkness so dense all is shadow. Why does this nearly full moon, so large and awful, cast no light? I make out the bumps of the other huts. Big, rearing shapes in the stalls where the horses rise on their hind legs in terror, their eyes white in the gloom bulging with terror. The howls from the unseen ones hurt my ears through the door slot, but I can also hear the whinnying and pounding hoofs of the panicked horses pawing ground, and the squealing of the pigs and bleating of the sheep, although I cannot see their stalls. Yet the streets are empty, as my eye adjusts to the darkness. Our village huddled in fear. The moon hung like a great silver platter, more omnipresent than before. Out in the mesas, the howling persisted, trapping us.

The hours pass and men of the village have gathered their rifles and stand now outside their houses, protecting their wives and young from what is to come. We pray for it to be soon, we want it to be over. The men’s eyes are like saucers as the night moves on. Each are within view of the others, and they make hand signals, pointing, patting their palms down; wait for it, do not move from where you stand is their meaning.

Still they did not come.

The monsters announced themselves in the hills but chose to remain concealed, staking their territory. The snarling was a bloody thunder that shook the ground to let us know they could take any of us anytime they wanted, conjuring awful pictures of what they looked like that were nothing compared to the horror of when finally we laid eyes on them.

But it was not to be that night.

We waited, sleeplessly, quivering in terror and the howls never stopped, never relented.

Remember, Pilar, the fear you knew then, it is in your voice now you tell your gunmen, and that is good, because they know you tell the truth. Look at their eyes now, in the saddles alongside you, exchanging glances with one another, disbelieving and believing and not sure what to believe.

Keep talking, the small one with the white-handled guns says.

I realize I have stopped speaking, the emotions too great and my throat choked with dust. But I have not cried, not yet. They must hear the whole tale. I continue my story and go on about that first terrible sleepless night, how we stood awake and counted the hours and the seconds with the men holding their guns and the women clutching their children until dawn broke, and by then we were tired and drained with fear and our nerves were raw. This was the werewolves’ plan, do you see, señors? They were tiring us out, grinding us down, robbing us of rest before they descended for the kill, driving fear into us as a picador spears a bull to make him weak for the matador. The howling ended at sunrise, and with daylight somehow we knew we were safe. A bleached-out sun rose over our meek village. Some said they were gone. Some said they would be back.

Two farmers walked into the hills, herding their sheep. I was told they saw a trail of blood and scattered rags leading into the brush. My townsmen followed the blood trail fearfully, and what they encountered caused them to drop to their knees and cross themselves before they buckled over and vomited. They brought him back in a bag. The mutilated remains of Manuel torn limb from limb and eaten by something much more powerful than a coyote.

We knew it was no coyote, señors.