Читать книгу Conscientious Objectors in Israel - Erica Weiss - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

The Interrupted Sacrifice

On the route to the Palestinian West Bank village of Susiya, the mood in the bus was excited and jovial. I was traveling with a group of Israeli conscientious objectors from Combatants for Peace (CFP) to meet with Palestinian ex-fighters, members of the same activist organization. At their meetings, Israelis and Palestinians tell their life stories and how they came to reject a militarized solution to the conflict between their two peoples. As we made our way out of southern Jerusalem and crossed into the Palestinian West Bank, the trip turned into a macabre guided tour of the memory sites of the Israelis’ experiences as soldiers. “You see over there,” Avi said, jumping up from his seat and jabbing his finger vigorously at the window, “behind the wall, you can see through the gap. Now! That one! We demolished the house there like two or three times.” Those who had served in the region between Jerusalem and our destination in the South Hebron hills pointed out the locations of incidents that had contributed to their refusal to continue military service. They told each other war stories in military vernacular, as many Israeli men enjoy doing; however, their disclosure of violent encounters in blunt terms gave their stories an uncanny twist.1 As many of their peers were waking up for a leisurely Saturday morning, these former elite combat soldiers, for whom the military had been a central part of their lives, were now en route to a solidarity event in a small Palestinian village.

I met Avi early in my fieldwork. He was an active member of Combatants for Peace and was often present at the events. When I would meet with him alone, outside CFP activities, he would express ambivalence about whether he would be attending the next event, saying he wanted to spend time with his young daughter. In the end, however, almost every time, he would be there, giving me a guilty grin and joking that he couldn’t stay away. These events were very important to the people I worked with, all of whom invested considerable amounts of their time in these activities. On that weekend and others, I had arrived early in the morning at the Tel Aviv central train station with a thermos of coffee and a few candy bars for the trip through Jerusalem and into “the territories” (ha’shetachim). I would go with them on their trips to the West Bank for meetings with their Palestinian counterparts in the organization or on solidarity events. Nearly all the Jewish members of the group had refused their service in years previous, especially during the wave of refusals in 2002 and 2003. Refusal by qualified individuals to perform military service is illegal, and all of my interlocutors among the former soldiers on the bus had spent time in military prison for their decision, their terms ranging from a few weeks to a year. They also had been dismissed from the military. Many felt, however, that their biggest punishment was social, harsh rejections by loved ones and strangers alike who could not accept what they had done. Despite this, they persisted in their activist activities, and in doing so calling often negative attention to themselves.

Heavy sacrifices are demanded of those who live in the region of Israel and Palestine, a site of struggle over land as well as over notions of community, belonging, and citizenship. In Israel, the main sacrificial economy is conducted through military service, in which the risk and time of service is exchanged for more complete citizenship (Peled and Shafir 1996, 1998) and moral capital (Klein 1999). Military service plays a central and much-discussed role in Israeli society, and the performance of this duty is foundational to the Israeli understanding of national community and belonging. However, as Antonio Gramsci (1971) noted, all hegemonic ideals are fragile, and thus the demand for sacrifice is renewed, resubstantialized, defended, and modified with each new generation.

There has been a long engagement in anthropology, as well as among some extradisciplinary predecessors and contributors, with research that implicitly and explicitly questions the legitimacy of state power. This questioning comes to a large extent in revealing, in full view, the strategies and techniques of state self-legitimization, methods of legitimizing power and violence, and, most damaging of all, the sleight of hand in making state power seem natural and pointing out the metaphorical man behind the curtain. Gramsci’s conceptualization of hegemony and its mechanisms has had long-lasting impact in the field. Other scholars have revealed state techniques of inclusion and exclusion on grounds of ethnicity, gender, and language as well as the suffering and paradoxes of agency that result from marginalization (see Appadurai 2003; Brown 1995; Das and Poole 2004; Guha and Spivak 1988). Meanwhile, several anthropologists have been explicit in their attempts to break the “spell” that the state seems to assert (see Appadurai 1993; Mbembé 1992; Taussig 1992). For example, James Scott has questioned the legitimacy of state power by considering the everyday methods by which people evade its governance and control over their lives (see Scott 1987, 1990, 2009). This work has dovetailed with and inspired much anthropological work on resistance by indigenous and marginalized communities. By and large, within this ongoing dialogue, scholars share a perspective that hegemonic inculcation is a more or less effective tool of state power and that resistance to state power comes either from those who are beyond the hegemonic reach of the state, from alternative or oppositional traditions, or who break the spell of state hegemony, whether in terms of older ideas of class consciousness or more modern conceptions that do not posit an a priori political form of consciousness.

In this chapter, I try to explain the context and process by which elite, dedicated soldiers came to resist the state through military refusal. Contrary to the social expectation that these soldiers would be the last to publicly refuse, I show why they were, in fact, the most likely to do so by virtue of their state-encouraged investment in the national narrative and the state-sponsored sacrificial economy of military service. This case prompts a reconsideration of anthropological understandings of the relationship between hegemonic inculcation and resistance. Resistance to the state and its authority is generally considered to come either from those outside its hegemonic or disciplining sphere or from those who fall short of state expectations of the ideal subjectivity for good citizenship. However, this case demonstrates that accepting and identifying with the state-supported hegemonic ideal does not preclude resisting the state. As scholars, we cannot ask only to what degree subjects subscribe to hegemonic values or about the extent of nationalist inculcation; we must also ask about the ideals to which, specifically, this identification and loyalty are directed. I find that inculcation does not imply loyalty to the state as super-subject but, rather, loyalty to the sacrificial moral economy, which, though emphasized through national initiatives as a cornerstone of good citizenship, engenders a turn of events that the state neither anticipated nor desired. Rather, the sacrificial economy acts as a golem, taking on a life of its own against the state that nurtured it in so many ways.

The 2002 and 2003 waves of refusals to perform military service surprised and beleaguered the Israeli Defense Forces. The refusals were distinguished by their occurrence in the higher ranks of the military, for example, by Brigadier General Yiftah Spector and many other officers. These conscientious objectors, including my interlocutors, were mostly elite combat soldiers, reservists in their twenties and thirties sent to the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Elite, here, refers to soldiers selected for volunteer special forces combat units, which hold a great deal of prestige for the difficulty and responsibility of the jobs. Their conscientious refusal to serve was, for most of society, unexpected because all indications had been that these soldiers were the most enthusiastic and the most dedicated among their peers to the sacrificial act of military service. They had been elevated to ideal types of soldiering, praised, iconized, and entrusted with the highest levels of responsibility. They were, as a military prosecutor told me, the face of the Israeli Defense Forces. Although the military and most politicians tried to limit the political fallout of their unexpected refusals, they were caught off guard. The refusals dealt a blow to mainstream confidence in the moral soundness of the nation’s elite soldiers, in the sense of collective conscience regarding military service and the military’s claims of purity of arms (tohar ha’neshek), as asserted in the Israeli Defense Forces doctrine of ethics.

The Sacrificial Idiom in Israeli Society

The idiom of sacrifice in Israeli society posits the soldier as sacrificial victim. The biblical story of akedat Yitzhak, or the binding of Isaac, is the dominant metaphor for discussing military service in Israel, with the soldier imagined as Isaac. This metaphor is found extensively in public discourse as well as the arts. Some scholars go so far as to claim that it is primarily through this myth that Israeli society speaks to itself (Sagi 1998; Weiss 1991). In the story, told in Genesis 22, God calls on Abraham to bring his beloved son Isaac to Mount Moriah, bind him, and sacrifice him. Abraham obeys, but at the last moment, he is interrupted by an angel of God, who tells him not to kill Isaac. Abraham, instead, finds a ram, which he sacrifices in substitution. God informs Abraham that, because he has demonstrated his faith and obedience, “I will surely bless you and make your descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky and as the sand on the seashore. Your descendants will take possession of the cities of their enemies, and through your offspring all nations on earth will be blessed, because you have obeyed me” (Genesis 22:17–18). Abraham then founds a community in Beer Sheva.2 The significance of this story for the metaphor of Jewish redemption in Israel through sacrifice is readily apparent. The theme of sacrifice leading to redemption and the foundation of a blessed and invulnerable nation clearly resonated with the Zionist ideology of redeeming the land of Israel and with Zionist leaders calling for difficult sacrifices from the new citizens of the fledgling nation engaged in near-constant wars (Sagi 1998; Zerubavel 2006).

However, what is not immediately obvious is how this myth overlaps with modern military service or how, exactly, this idiom of sacrifice structures contemporary reciprocity between violence and redemption. The Isaac of the biblical story was an unknowing child, hardly the ideal soldier or a galvanizing image of heroism. Isaac’s image has therefore undergone modification in Israeli public culture (in literature, theater, and art) from that of an unknowing child to an exemplar of a whole generation of youths willing to sacrifice themselves for national redemption (Feldman 1998, 2010; Sagi 1998). Poems and literature of the early settler generation venerate this image of Isaac in unqualified terms. Such efforts received and continue to receive state patronage and promotion. A poem of the settler period, by Uri Zevi Greenberg, which is still read publicly on Israeli Memorial Day, invites,

Let that day come …

when my father will rise from his grave with the resurrection of the dead

and God will command him as the people commanded Abraham.

To bind his only son: to be an offering—

… let that day come in my life! I believe it will (1972: 145–147).

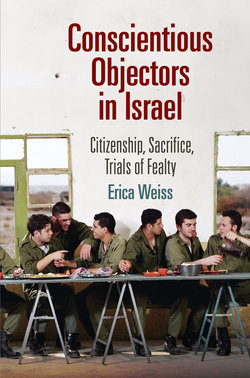

Sacrifice here leans heavily toward self-sacrifice; the soldier is both the sacrificial victim and the sacrificer, the one who makes the sacrifice, is responsible for the act, and accrues the moral benefits of it. The move toward self-sacrifice in return for redemption has, unsurprisingly, produced some slippage in the idioms of sacrifice, and many scholars have noted Christian imagery in this secular nationalist articulation of sacrifice (Feldman 2007). One of the clearest examples of this slippage is a well-known photograph by Adi Nes, which sold for more than a quarter million dollars at auction, the highest price ever paid for an Israeli photograph. The piece is untitled but commonly referred to as the Last Supper (see Figure 1). It formally replicates Leonardo da Vinci’s painting of that name, showing Jesus in his final evening with his twelve apostles, but substitutes male Israeli soldiers for Jesus and the apostles. The scene is set in a boisterous mess hall at mealtime, and the central soldier, replacing Christ, abstains from the fraternizing around him and bears a look of melancholy and premonition.

Figure 1. Untitled (commonly called The Last Supper), 1999. Color photograph by Adi Nes. Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

This photograph is not an unproblematized celebration of sacrifice. Using the Christian metaphor, it suggests inauthenticity for Jewish culture and plays with the dichotomy of voluntary self-sacrifice and communal betrayal of the individual. Criticism of sacrifice through military service began in earnest in the 1970s. Iconic authors such as Amos Oz, Yehuda Amihai, Yitzhak Laor, and A. B. Yehoshua have all used the idiom of akedat Yitzhak to criticize the nation’s demand for sacrifice from its youth, pathologizing the intergenerational relations it implies as well as pointing out the impossibility of normalization (a high Zionist goal) under conditions of continual self-sacrifice. Literary scholars understand this criticism as representative of larger shifts in the ethos of Israeli society away from a veneration of sacrifice. Despite forty years of intermittent critique, sacrifice through military service continues. Likewise, despite the increased critical awareness that class, ethnic, and gender boundaries are created through the hierarchy of sacrifice in the military, these are far from being overturned. There are, then, many relationships to, and investments in, the Israeli state’s framing of good citizenship through the national sacrificial economy.

Living the Nation

Avi grew up in a middle-class family in a suburb of Tel Aviv, where he still lives with his wife and daughter. He is the grandchild of Holocaust survivors, Jews from central Europe. He had been a commando and refused in 2002, together with many of his fellow commandos. Avi was very active in the Combatants for Peace organization. In 1990, at age seventeen, his heroic ambitions were informed by a romantic attitude toward the idea of communal sacrifice. This was partly because he had been exposed almost exclusively to the sincere veneration of military sacrifice as presented in public and educational events and activities of commemoration, had not yet encountered critical literature, and was relatively unaffected by the ongoing disenchantment with sacrifice in the arts. But he also recognized that joining the military was his rite of passage into full participation in Israeli society, and he pursued it with vigor. Avi recognized that he would accumulate both tangible and intangible benefits through military service. He spoke to me at length about the ways in which he saw his masculinity and citizenship as dependent on service. He knew that his service would endow him with moral worth and respect and transform his moral status in society, as Henri Hubert and Marcel Mauss (1981) insist sacrifice is meant to do. Iris Jean-Klein (2000, 2001) demonstrated how the domestically based nationalist initiatives of ordinary persons, everyday and self-motivated forms of inculcation with nationalistic ideals in Palestine, are often more significant than organized initiatives. Considering the eternal question of why people would agree to kill or die for the nation-state, Philip Corrigan and Derek Sayer (1985: 386) suggest that such willingness is partly due to strategies of substantialization by which the obligatory is converted into the desirable. Though Avi’s service was legally required, he pursued it with vigor because of the many benefits of participation.

In joining an elite unit, Avi was also signaling high ambitions vis-à-vis a hierarchy of substitutions in military sacrifice. Not all service is the same, and therefore not all endows the same degree of transformation in moral status. Military service entails hierarchies of sacrificial value, as is common to organized sacrificial practice (Lambek 2007; Willerslev 2009). In making great sacrifice in the Israeli military, one does not seek out death or injury; however, the sacrifice is greater with greater loss in an economy of negation. Taking on what is socially recognized as additional risk, physical and mental agony, discomfort, and time contributes to the sacrificial hierarchy of military positions. Avi could have taken an office job close to home, which would have involved little danger and hardly any responsibility and would have allowed him to go home at the end of each day, but he told me he never considered such a position. Intelligence work carried somewhat more cachet, but the real elite choice was combat duty. Likewise, not all combat duty is equal; jobs such as pilot and commando carry far more prestige and a greater sense of exclusivity than rank-and-file positions do because they are more physically and intellectually challenging, a hierarchy well recognized throughout society (Kimmerling 2009).

Avi went through an excruciating selection process and subsequent training to become a commando. He would often in conversation bring up his mindset when he joined the army as a teenager, sometimes sarcastically referencing his naïveté, though sometimes with chastened esteem for his intentions (for further discussion of the role of the military in society, see Helman 2000; Ben-Eliezer 1998). On one of the latter occasions, during a conversation over a cup of instant coffee, he told me,

I wanted to give the most.… I felt like I needed to do the most that I was capable of. I believed that I should give the most, because that was like … an investment, that would carry through the rest of my life. So I only saw the possibility of giving 100 or 110 percent. But also, in my family there was a very big emphasis on volunteerism, trying to do the most you can without counting points, which you know, is big in the Israeli ethos as well. I would volunteer with my mother a lot, helping poor families or new immigrants [olim chadashim]. I really got from my parents, and also my teachers, that, because this is a new country, that everyone needs to give up a lot, put in a lot of effort for the experiment to work. I thought if I did something really hard, then my generation could set the country straight, make it stable and like … permanent or something. And I could be a hero in the process, so I saw no downside at all.

His words resonate with Jean-Klein’s (2001) claims that nationalization often allows people to realize their fantasies as well as fulfill their political-moral commitment, which are often intertwined. Avi and other refusers found in the hegemonic demand for military service a coincidence of their fantasies, their cultural values, and a chance to advance their moral worth.

Such sacrifice is a kind of mediated self-sacrifice. The “mere” and “voluntary” acceptance of this risk is a sacrifice in and of itself, a precondition for the amplified possibility of injury or death. This sacrifice is not selfless as much as it is overdetermined by what I call a coincidence of the good in society around military service as communal sacrifice. For the individual, the sacrificial economy involves benefits to material and moral worth from participation. Hubert and Mauss note that abnegation in sacrifice and its rhetoric are not without their rewards: “The sacrificer gives up something of himself, the victim, but does not give himself. Prudently he sets himself aside. This is because if he gives, it is partly in order to receive” (1981: 100). As Foucault’s (1991) descriptions of the self-disciplining associated with good citizenship practices make clear, however, there are likewise benefits to the state’s ability to govern. In the Israeli case, the performance of military service is encouraged by state educational initiatives and widespread social pressure to do the most to serve society, an ethic of volunteerism, the moral virtue of difficult service, and benefits to masculinity as well as personal career ambition and the social respectability that accompanies service in Israeli society.

Avi would often refer to combat soldiering as though it were coterminous with Israeli citizenship, referring to his service in an elite unit as the universal Israeli experience, as most Israelis do whether they have had this experience. In fact, combat roles are taken by only some 10 percent of Israelis, and even fewer serve in elite units. The ideal combat soldier and, thus the Israeli ideal as described by Meira Weiss (2005), is Ashkenazi, male, physically able, and attractive. Tamar Katriel describes the demographic group of soldiers like my interlocutors as “elite pioneers from Eastern and Central Europe for whom the official tale of Zionist settlement has served as a powerful self-defining and self-legitimizing social discourse” (1997: 150). Reciprocally, Danny Kaplan (2008: 418) demonstrates the national emotional investment in the welfare of this hegemonic group of Ashkenazi men, especially when engaged in the sacrificial economy of military service.3 Many Israelis, and many combat soldiers, do not fit this description, but nearly all of my interlocutors conformed to this mythic ideal, though they avoided discussion of their demographic homogeneity. Their uncomplicated relationship to the national ideal of sacrifice allows them to relate to this ideal without self-doubt. This means that their inculcation was very deep and enmeshed with their sense of identity. The official narrative of the state, with its European past and New Jew present, is also their personal narrative. For those who are not part of the hegemonic group, the experience of personal divergence from the ideal—be it a family history in the Middle East, a disability, not being Jewish, or being an immigrant—is noticeable from an early age and will always be an inherent obstacle to complete identification with the national ideal. Despite demonstrations that combat casualties are increasingly from peripheral social groups (Levy 2006), such groups remain peripheral. All military positions are open to all, and acceptance is meritocratic; however, as is the case in U.S. universities, admission often goes to those who were raised with opportunities and is granted with an eye to satisfying institutional ideals.4

Refusers most often described their intentions in joining the army as “wanting to be a hero,” and, in fact, two documentary films that take up Israeli conscientious objection, I Wanted to Be a Hero (a 2004 Israeli film by Shiri Tzur) and Raised to Be Heroes (a 2006 Canadian film by Jack Silberman),5 are named according to this refrain. It is worth considering the subjectivity that informs an understanding of one’s actions as heroic. It is, I believe, best described by what Gayatri Spivak (2004) calls the ability to metonymize the self, to imagine the self in an active relationship with the state, the opposite of subalternity. The ability to engage in sacrifice, then, is not compatible with the subaltern subject position, because it involves an understanding of the self as hero and citizen and of self-sacrifice as a contribution to the (appreciative) community.

Many who would become refusers initially saw their military service as a personal intervention in the arc of Jewish history. When I asked Avi about his parents’ military experiences, he told me,

The truth is, my father had a very traumatic military experience. He was in war and he was traumatized by it, and for me this fact was always kind of embarrassing. Well, not really embarrassing exactly. I knew it wasn’t his fault. I guess I just saw it as his being too close to exile [galut], which made him kind of soft. You know Woody Allen? Not that extreme, but a little in that direction, with the glasses. (I got contacts.) Anyway, I felt like I was much stronger and with self-confidence, and I was jumping at military service as a chance to correct for my father’s service.

This idea of correcting the past, the personal past being deeply entwined with the national past, was very common. Many talked about feeling as if their service was a penance or even an atonement for their relatives who died in the Holocaust.

Dan was a pilot before he refused. Like Avi, he was Ashkenazi and from a middle-class family living in the suburbs of Tel Aviv. He also described his ethical intervention:

They teach you in school that since the Jews left Israel it has been one pogrom after another, only anti-Semitism everywhere. And then in the most shameful moment, the Holocaust [Shoah], only a few Jews in Warsaw even put up a fight, but it is too little too late. To me, I couldn’t understand why no one thought about fighting back a few thousand years ago! Only now do we have the self-respect to defend ourselves?!

Such statements clearly illustrate Spivak’s observations regarding metonymizing the self and the identification with history. They also resonate with Claudio Lomnitz-Adler’s (2003: 142) observation that national sacrifice is often imagined as an attempt to place oneself in the national narrative. The state is likewise invested in this project. Because military service is understood as sacrifice, the state must legitimize it in ethical terms. State discourse encouraging this identification is conveyed through a number of channels. Dan mentions schools and indeed education is one of the prime sites of inculcation. Learning that “since the Jews left Israel it has been one pogrom after another” is an example of the Zionist periodization of Jewish history that romanticized the early Israelites while belittling the two thousand years of Jewish life outside Israel. This narrative characterizes both ancient and modern Israel as authentic, strong, and secure, in contrast to Jewish life outside of Israel, which is stereotyped as adulterated, weak, and vulnerable. As we can see in Dan’s statement, this historicization legitimizes the state and gives ethical purchase to military service. History class, along with Bible studies, motherland studies (moledet), and geography, have since the beginning of the state been culled by educators to convey the Zionist worldview. One of the central concepts of this worldview is the idea of peoplehood or nation, called am in Hebrew. This concept groups people by ethnicity rather than geography or ideology, and attributes a common destiny and collective intentional to the group. It is used most commonly to describe the Jewish people, am yisrael (for an excellent exploration of this concept, see Dominguez 1989). It is central to Zionist education as a conceptual tool through which not only to explain Jews as a naturally cohesive national group, a difficult task considering the far-flung cultural backgrounds of Israelis, but also to naturalize its enemies into opposing groups.6 Am is part of a political discourse of peoplehood that regulates individual and collective experiences to be understood through the ethnic category. Thus, it is common for people in Israel to attribute collective intention, as in “the Arabs rejected the deal,” “the Jews demanded a period of calm,” “they do not value life,” or “Israel wants peace.”

In speaking with other conscientious objectors about the sources of their strong identification with the state and willingness to sacrifice, many referred to their children. Many had difficulty remembering the details of their early childhood educational experiences, but their political conscientiousness as refusers made them attuned to the role of the state in their children’s lives. On three occasions, refusers noted their distress when their children brought home pictures of smiling wholesome soldiers, either a handout or drawn by the child with the encouragement of the teachers. Others mentioned their discomfort that they lost domestic control over the meaning of Jewishness because of the way the state seemed to insert itself into Jewish holidays in school. Uri Ram similarly notes that “Israeli state ceremonies are imbued with Jewish religious symbols and Jewish religious holidays are today imbued with nation-state symbols” (2011: 21; see also Handelman 2004).

Discussing their teenage years, my interlocutors described the confluence of state and private influence that acted in harmony. Military officers were brought into the schools, and teachers brought students to military bases for exposure and training. Classes observed national commemorations celebrating military sacrifice and wrote letters and poem to personalize the experience. Nearly everyone participated in the Israeli Scouts (Ha’Tzofim), a Zionist youth movement that promoted a sense of volunteerism, leadership, a love of the land of Israel, and a strong sense of identification with their Jewish heritage understood in a secular way. For example, Dan recalled climbing to Masada with this group. Masada is a rock plateau near the Dead Sea, and was the site where the Jewish rebels resisted the Roman Empire after the destruction of the second temple. Understanding that they could no longer resist the Romans, the Jews committed mass suicide. Masada has become a site of pilgrimage for modern Israelis, who read in the plight of the rebels their own desires for freedom and political sovereignty (for more on Masada as an Israeli pilgrimage site, see Zerubavel 1997). Dan said,

We climbed all the way up there, and it was so hot, but the physical aspect of it only added to it. In that moment we were heroes, we were pioneers in the completely innocent and sincere (chen) in a way you cannot access as an adult. And when we got to the top they [the scouts leaders] told us to say “Masada will not fall again,” and we yelled it off the edge into the desert. They do it at exactly the right age, when you are so intense and sincere and you are looking for meaning. And even today that I would never bring my kids to Masada, it’s like, not an interpretation I can support, it still makes me emotional to remember it and how I felt.

Dan’s words indicate a strong identification with the hegemonic narrative of history and the need for an aggressive posture of self-defense, as taught through public education and fleshed out at home. In Israel, much of this emotional agency is developed at home, through family stories and losses. There could be no substitute for military service to fulfill what these soldiers believed was their authentic realization as post-Holocaust, native-born Israeli men. Using Gramsci’s (1971) notion of hegemony as intellectual and moral leadership, or determining what is obvious and right, one sees that the historical imagining and subjectivity vis-à-vis sacrifice encouraged by the state is very much what these soldiers identified with and saw as building blocks of their self-worth.

The Interruption of the Sacrifice

These conscientious objectors all completed their basic three-year service and did reserve duty for several years before they ultimately decided to refuse, even though their disillusionment with their military service had begun soon after enlistment. For Avi, it began even before he was deployed.

I remember one of the very first days, they were handing out equipment, and they handed everyone a nightstick. It really surprised me, with the gun I had all these images of using it like in movies I had seen, but I couldn’t imagine using this nightstick. It seemed so barbaric! I thought about what it would be like to hit someone with it, and I pictured bones cracking under its force. I hated the thing and I decided I would never use it. Of course, later I did use it because often it is the appropriate weapon for a situation.

Refusers narrated the various ways in which their service did not fit their preconceptions about who the aggressor would be in the situations they encountered as well as about who would pay the price of their service. Uri’s experience did not match his expectations. Uri had Israeli parents but grew up partly in California, where he befriended many other children of Israeli parents, a small group of whom went to Israel to join the military instead of going to college. We spoke in English.

When I joined I expected missions to make sense, that we would go to find a specific terrorist, and deal with him professionally, effectively and surgically. But at some point, I began to realize that so many of the missions were arbitrary, and so messy. I remember going to this house looking for someone with a name given to us by intelligence. We got there and of course there were only women, kids, and old people there, because that’s what happened every time. We had to order the men and women apart, the kids were screaming, people crying, always the same. The next week we were given another name, but were dropped off at the same fucking house! There we are again with the same women, ordering them around all over again, in the same absurd ritual, like some choreographed dance. And I knew they recognized us. It was embarrassing! To be both incompetent and cruel … maybe one or the other [laughs]…. I really began to understand what was going on when my commander told me that it wasn’t a good thing if things were “too quiet.” I began to see in everything we did that the army was instigating conflict, not just responding defensively.

The distinction between instigation and response is a matter of moral significance for the Israeli military, which self-identifies and self-legitimates as an exclusively defensive force. Other refusers described being disturbed to discover that they had developed a slowly grown addiction to power.

For a long time, the refusers generally did not talk about such things with their fellow soldiers and would push their doubts out of their minds. Avi told himself, “You shouldn’t change your beliefs about everything all at once” and “It’s not always the time for soul-searching.” Even with his doubts, Avi believed for a time that he was helping by being in the Occupied Territories, that he was keeping some of the excesses of other soldiers in check. This sense faded, however.

One day we were told to evacuate a house that was going to be demolished. We got there and told the family that they had one hour to leave. There was, of course, rushing around and crying and begging us to change our minds (as if I made that decision). After everyone was out, and they were going to knock it down, one of the women came running to me and begged me to go back inside because her daughter had forgotten her school backpack, which had all of her school supplies inside. My commander would not allow it—for him it was just a school bag. So, I had to tell her no.… But what does it mean “I had to”? From her point of view, and from any perspective that matters, I told her no. There I was trying to be the “good soldier,” and there I told her no, and that’s how the little girl will remember me, and if I am really honest, she’s right about me, or she was. And I thought to myself—this is me sacrificing for my country? It can’t be. I was the schmuck standing there on this ridiculous premise, when even a child can see that is not the truth.

Avi had conceptualized himself as Isaac until he found himself with the knife in his hand, until he saw himself as Abraham. His commentary indicated that, being part of a chain of command, his dissatisfaction with the situation at hand did not matter; he had not allowed the girl to retrieve her backpack, not because he did not want to or because he hated her, but because he was only a single, notorious, and maligned cog in the machine. He stopped seeing his service as a sacrifice, however. Before this encounter, he had felt great doubt and ambivalence about his service, and furthermore attributed moral value to his ambivalence, to being a good soldier, but in the moment of crisis realized the irrelevance of his sense of ethics to his actions and their consequences. He realized that he had unintentionally sacrificed ethics. It was a moment in which the alignment of moral good and what was good for the state split, and Avi found himself, in Gramscian terms, no longer consenting but coerced with regard to his ethics. He was prevented from taking action by fear and an inability to conceptualize what dissent would look like within that physical space; that is, he could not imagine the possible actions that he could have taken.

Avi found himself in a situation in which, through military logic of self-preservation, he was not the victim of sacrifice, as he had imagined, but, rather, that the most of the loss in his daily experience was Palestinian loss. This does not mean he was not frequently in mortal danger; he was. Despite being prepared for self-sacrifice, he felt that he was demanding more from Palestinians than was ethical under the everyday moral code with which he had been raised regarding respect and dignity in human relationships. Whereas the discourse concerning just causes for military sacrifice in Israel concerned strong and clear beliefs regarding war, national boundaries, and the enemy, the policing missions of occupation violated them.

Others echoed similar sentiments. I heard such thoughts voiced, for instance, toward the end of an olive-picking solidarity event in the West Bank organized by Combatants for Peace. My hands had grown sore from plucking clumsily at the small bitter green olives that grow in that region. I stepped aside to stare pointlessly at them and found myself next to Dan, who had come away from the trees to get some water. As we stood there, an army jeep drove by carrying young soldiers who were monitoring our activities. They waved and chuckled at us, I supposed because they were amused by what are often described as the naive efforts of leftists. Ironically returning their wave, Dan told me,

You get into the mode of military logic, the way you are trained to protect yourself and your soldiers, and there is no choice but to follow it; if not, their lives are on your hands. But then you catch yourself doing things which are just not OK, and certainly not up to the standards I had when I enlisted. That is what happens with the whole human shield thing, which I saw some guys do. When you see it in the newspaper it looks awful, but when you are there and you get deep into the military logic, it makes perfect sense to you. When I realized that there was no way to be there and not follow that logic, I knew I couldn’t be there anymore.

Dan was expressing, especially with the example of the human shield (the use of civilians as cover, forbidden by military policy), how, through the structure of military training, the sacrificing soldiers were replaced as victims by unwilling Palestinians. To say that the soldiers expected to be victims sounds extreme, but it does not mean they expected death. Rather, it refers to the mediated self-sacrifice I have described, to exactly what is meant by the English phrase often used to describe soldiering: as individuals “putting themselves in harm’s way” for the greater good. For Dan, the realization that the heaviest price was not being extracted from him interrupted his understanding of his military service as sacrifice. These soldiers were certainly exposed to grave danger and could have been killed many times, but, for them, this danger did not characterize their service. The logic of military service stresses the avoidance of loss, whereas the logic of the sacrificial economy demands negation and loss. After a long pause, Dan added, “When I understood there was no good coming out of it, that we weren’t helping anything, in fact the opposite, I wasn’t willing to risk my life for that anymore. After that, I was basically paranoid about getting injured or something, because if I lost a leg, I wouldn’t be able to see myself as a war hero, I’d just be a cripple.” In his consideration of voluntary death among the Siberian Chukchi, Rane Willerslev (2009: 701) differentiates voluntary death from suicide, with voluntary death (in proper context) conforming to the sacrificial requirement of furthering life through the taking of life. After Dan no longer saw his service as sacrifice, he feared any loss would be suicide-like, pure loss with no redeeming value. He was, in Lomnitz-Adler’s words, haunted by the “specter of meaningless death” (2003: 18), of a meaningless killing.7

Avi’s and Dan’s accounts had many elements in common with other stories of refusal I collected. Doubt was followed by the persistent belief that one could make a positive contribution, be the “good soldier” and prevent aggression. This period of ambivalence was very often followed by a crisis triggered by an encounter, often with a child or a woman read by the soldier as undoubtedly innocent (as opposed to young men, who are always suspect).8 Seeing themselves otherwise and fantasizing about the Palestinian gaze was universally a gut-wrenching experience for Israeli military refusers. The intersubjective experience is not a comfortable space to inhabit, and as Michael Jackson notes, is rarely achieved willingly but instead involves a painful epiphany of seeing one’s own stance invalidated in the face of another (2009: 239). This invalidation was especially devastating for these soldiers, who invested so much of their moral worth in their willingness to sacrifice in the culturally sanctioned method of military service. The moral crisis caused a realization of a hiatus in their understanding of themselves as self-sacrificing and of the reality of soldiering, which, afterward, they interpreted politically to mean that service was unethical and that they must refuse it. Retrospectively, they described their years of service and efforts to maintain faith in the sacrificial meaning of this service as spent in denial.