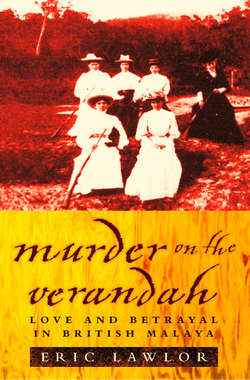

Читать книгу Murder on the Verandah: Love and Betrayal in British Malaya - Eric Lawlor - Страница 7

PREFACE

ОглавлениеOn 23 April 1911, Ethel Proudlock, as was her custom on Sundays, attended Evensong at St Mary’s Church in Kuala Lumpur. She was well known at St Mary’s. From time to time she helped with jumble sales and had recently joined the choir. After the service, a friend invited Ethel to join her for dinner, but she declined. Her husband was going out for the evening, she said; it would give her a chance to write some letters. Then, after checking that the hymnals were in order, she walked home and killed her lover.

Claiming self-defence, she told police that William Steward had turned up unexpectedly that evening and tried to rape her. None of this was true. Steward was there because Mrs Proudlock had invited him, and he died – shot five times at point-blank range – after telling her he was ending their affair.

The Proudlock case, the basis of ‘The Letter’, the most famous of Somerset Maugham’s short stories, galvanized British Malaya. Some Britons insisted she was innocent, but the evidence against her was overwhelming and, after a trial lasting nearly a week, Ethel Proudlock was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to die. Preparations to hang her were well advanced when the Sultan of Selangor intervened. Citing her youth and the fact that she was a mother, he granted her a pardon. But the trial had unhinged her. Ordered to leave Malaya, Mrs Proudlock, with her husband and three-year-old daughter, returned to England a virtual invalid.

Until she was arrested, there was little to distinguish Ethel Proudlock from other members of the British community. Like them she was middle-class, seemed perfectly conventional and, to all appearances, was happily married. Ethel Proudlock fitted in, her defenders said. She couldn’t possibly be a killer; she was one of them. But the fact remained: Ethel Proudlock had killed. Why?

Some suggested that she might be mad. Mrs Proudlock was dangerously unstable, they said; a person whose violent mood-swings had long been the subject of gossip. Others blamed vindictiveness. Ethel made a bad enemy, according to this view. Offend her even slightly, and she was implacable. A third group – this one made up of Kuala Lumpur’s Chinese and Malays – attributed the killing to arrogance. Ethel was a member of Malay’s ruling caste and, as such, thought she could do as she pleased. When she pulled the trigger that night, she was exercising the prerogatives she believed were hers by virtue of her station.

There is a fourth, more plausible, possibility. When Ethel married, she was a girl of just nineteen whose sheltered background can hardly have prepared her for the pressures and artificialities of colonial life. Might it be the case that those pressures proved too much for her? Answering that question necessarily raises others. What were the British in Malaya really like? How did they comport themselves? Did they enjoy the country? What did they see as their role there? Were they, as some have claimed, a force for good? Or were they opportunists?

Colonial Malaya, often described as ‘Cheltenham on the equator’, has not lacked for study. Its politics have come in for much attention, as have its economics, but about the British themselves we know surprisingly little. The oversight is regrettable. While the society they created was neither as complex as India’s or nearly as grand, it was no less intriguing. No one clung more tenaciously to their ancestral ways than did the British in Malaya; and no one was more convinced of their natural superiority. The institutions they created in that country may well have been unique.

Complicating any effort to take the measure of these people is a controversy set in motion some seventy years ago by Somerset Maugham. Maugham is as much associated with Malaya as Kipling is with the British Raj but, unlike Kipling, who was born in India and spent much of his life there, Maugham visited Malaya only twice: for six months in 1921 and a further four in 1925–26. Yet out of that short acquaintance came his most enduring achievement – a group of short stories bringing Malaya so vividly to life that people named it Maugham Country.

Maugham’s portrait of Malaya’s colonials is less than flattering. The planters and officials in his stories are dull and mediocre, ‘eaten up with envy of one another and devoured by spite’. Their wives are even worse: ‘The women, poor things, were obsessed by petty rivalries. They made a circle that was more provincial than any in the smallest town in England … They were sheep.’

Cyril Connolly said of Maugham that he had done something never before achieved: ‘He tells us exactly what the British in the Far East are like.’ The British in Malaya did not agree. They said they’d been betrayed. They had taken Maugham into their homes, introduced him to their friends, made him a guest at their clubs. And for this, he had defamed them. Who are we to believe? This book is an attempt to answer that question.

One thing can be said at the outset: the British changed when they went overseas – a change that was commented on again and again. As one visitor put it: ‘Two Englishmen, one here and one at home, might easily be men of different race, language, and religion so different is their outlook and behaviour.’

In so far as it is useful, I have tried to let these people speak for themselves. This is their story after all and it seems only right that I let them help me tell it. I also draw much on the Malay Mail. With few sources at my disposal, the Mail proved a godsend. Kuala Lumpur’s only daily newspaper during this period, it is remarkable not just for the quality of its writing, but also for its knowledge of those whom it was writing about. Recruited in England, the Mail’s editorial staff did not simply cover the British community, they formed part of it. They belonged to the same clubs, worshipped at the same church, played on the same rugby teams, shared the same beliefs. At a time when the British in KL (as Kuala Lumpur was colloquially known) numbered between seven and eight hundred, the people these journalists wrote about were, in many cases, known to them personally. I owe the Mail a debt of gratitude. Without it, my job would have been very difficult.

Before I begin, a little history. Britain, in the shape of the East India Company, acquired Penang in 1786, Malacca in 1795, and Singapore in 1819. Seven years later, the three territories were amalgamated for administrative purposes. Now called the Straits Settlements, they were ruled from India until 1867 when Penang, Malacca and Singapore became a crown colony and found themselves the responsibility of the Colonial Office.

Now the rest of Malaya beckoned. Uncharacteristically, Britain hesitated – but not out of any high-mindedness. Its reasons were practical: Westminster did not care to become embroiled in Malaya’s Byzantine politics. Besides, as long as London controlled the Straits of Malacca – crucial if it were to protect India and safeguard its trade with China – it had little need of Malaya. For years, investors in the Straits Settlements had complained to Britain that it was failing to protect their interests. They had invested large sums of money in Malaya’s tin mines, they said – money that the interminable political squabbling in that country now placed at risk. Britain ignored them.

Then the money men changed tack. If Britain would not protect them, London was warned, they would find a country that would. (Germany and Russia were mentioned as likely possibilities.) London was all ears now. The last thing it wanted was a rival in a part of the world it considered its own. And so, in 1874, the government reversed its policy, making protectorates of Perak, Selangor, Sungei Ujong (part of Negri Sembilan) and Pahang, four territories that became the Federated Malay States (FMS) in 1896. Thirteen years later, Britain extended its rule again, this time to embrace the four northern states of Kelantan, Trengganu, Kedah and Perlis, long controlled by Siam. When the lone hold-out – Johore – submitted to British rule in 1914, Britain controlled the Malay peninsula as far north as the Siamese border, an area measuring 70,000 square miles. (The five newcomers declined to join the FMS and were known collectively as the Unfederated Malay States.)

In Malaya, the British employed a formula known as indirect rule, recruiting pliant elites – in this case the sultans – who became, in effect, front-men for colonial rule. The fiction put about was that the sultans, Malaya’s traditional rulers, enjoyed considerable discretion, turning to the British only when they needed help. Each state had a Resident – a senior civil servant – who was said to ‘advise’ the sultan. But no one was in any doubt as to what would happen if that advice were ever disregarded. Essentially, the sultans had a choice: they could do as they were told or be replaced by someone who would.

Because the country was never formally annexed, the British in Malaya convinced themselves that their rule owed nothing to force. This was far from being the case. True, force was rarely used, but no one in Malaya ever doubted it remained an option. When, in 1875, Malays assassinated the first Resident of Perak, the British mounted a punitive expedition that left scores of people dead.

Finally, a few words of explanation. During the period 1900 to 1910, my primary focus in this book, there were three ethnic groups in Malaya: Malays, Chinese and Indians. When referring to all three, I use the term ‘Asians’. The term ‘Malaya’ needs explaining as well. When Mrs Proudlock went on trial in 1911, Malaya comprised the Federated States, the Unfederated States and the Straits Settlements. As a single political entity, Malaya did not as yet exist. The term is convenient, however, and, as others have done, I use it here to mean that part of the Malay peninsula under British rule.

The dollar I mention from time to time is the Straits dollar which, during this period, was worth slightly less than half a crown.