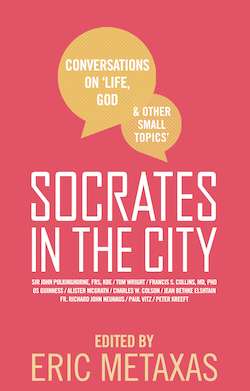

Читать книгу Socrates in the City: Conversations on Life, God and Other Small Topics - Eric Metaxas - Страница 5

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Good evening, and welcome to Socrates in the City. My name is Eric Metaxas, and I will be your server for the evening. Anytime you like, you can make your way over to the salad bar, and in a few moments I will be back to tell you about our specials. Thank you.

I’m amazed by the crowd tonight. I’m curious: How many people are here at a Socrates event for the very first time? Would you raise your hands? Amazing.

Now be honest. . . . How many people are here tonight for the last time?

Before I get into anything profound, I want to say that we are anxious to stay in touch with you. We’ve been having administrative problems, because I am the administrator.

I hide behind the idea that I am a right-brain person; so this isn’t easy for me. They were on your seats a moment ago, blue or salmon-colored index cards. Blue or salmon. Salmon is kind of a pink, for those of you who don’t know that.

If you would do this, while I’m talking— certainly not while Dr. Polkinghorne is talking— but if you would, before the evening is over, put down your name and address, even if you have done this before, because we’re starting a new database, and I know that we’ve lost a few of you. Put down your name and address, SAT scores. . . .

Socrates in the City, for those of you who are new to these events, is designed to help busy New Yorkers take a moment out of our busy lives to stop and think a bit more deeply about what life is all about— to answer the big questions or to try, at least, to begin to answer them. Socrates famously said, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” I think many of us could probably do with a bit more self-examination. I know I could, and having speakers like Dr. Polkinghorne is meant to make that process a bit easier for us.

Of course, these events are only the tip of the iceberg. We would like to think that these events, these evenings, would kick off the Socratic process in each of us and that in between these events, you might read one or more of these books that are available on the book table. I recommend them very highly to you. We’re selling them at no profit to us. They’re wonderful books, and they’re wonderful to give away to your particularly unthoughtful friends. Of course, Dr. Polkinghorne will happily autograph his books, and I will autograph any of the other books that you would like to have autographed.

By the way, I should say that tonight’s event is generously being sponsored by the New Canaan Society, a group I had a very small hand in founding almost nine years ago. The New Canaan Society is a men’s fellowship that has, as its modest goal, the idea of helping its members be better husbands and fathers. We have dinner events in New York about once a month, among other things, and if you would like more information, we’ve got some literature on our front table.

We proudly count David Bloom, the NBC correspondent who recently died in Iraq, as one of our members, and he certainly was a dear friend.

So, to tonight’s subject: belief in God in an age of science. In the last one hundred years or so, many people have come to think that somehow “modern man” ought to be beyond believing in God. This idea has continued to enjoy a kind of strangely unchallenged popularity and has rather dramatically affected our culture, often negatively, as is the case with many unchallenged assumptions. I thought it behooved us to apply a bit more rigor to our examination of this matter than we have generally applied, and tonight is meant as a small initial application of that selfsame rigor. And I can repeat that sentence.

It has come to my attention that for some of the very brightest minds on our planet, there is, in fact, no disparity between the truth as promulgated in the biblical faiths and the truth promulgated by scientific discovery. But, as I say, we don’t often hear from those bright minds, and I’m very happy to remedy that tonight, with, if I may say so, one of the brightest. I think no matter where you come out on this issue, it will do us all kinds of good to hear from our guest speaker tonight, Sir John Polkinghorne.

I first came to hear Dr. Polkinghorne in Cambridge, England, just over a year ago at a C. S. Lewis conference that was held at Oxford and Cambridge universities. As luck would have it, Oxford and Cambridge universities are located in Oxford and Cambridge, England, respectively. It is all a little too neat, isn’t it?

In any case, I was very taken with Dr. Polkinghorne, and I asked him to come to New York City and speak at Socrates. And, of course, here he is.

Now, I have to say that we have never had a Knight of the British Empire at Socrates in the City, at least not that I know of. I’m not quite sure what the protocol is exactly. I assumed that the fact that Dr. Polkinghorne was a knight didn’t mean he would necessarily be wearing armor. Just to be on the safe side, I asked him not to wear any armor. It seems that he has complied with my request, unless he’s hiding a Kevlar vest under there, which we will never know.

But I said to him that if he did feel compelled to wear armor, he might at least wear his beaver up, like Banquo’s ghost in Hamlet, so that we might better hear what he had to say.

Thank you to all the Banquo fans out there for laughing at that.

A bit of a word on our format. Dr. Polkinghorne will speak for about thirty-five to forty minutes, and then we will have plenty of time for questions and answers. If you have a question, I implore you, please, to step to the microphone here. I implore you to be brief and to speak clearly— and to end your question with a proper punctuation mark. I think you know what I mean.

Nothing like a punctuation-mark joke to get the crowd warmed up.

Now, to introduce the Reverend Dr. John Polkinghorne, KBE, FRS, DDS, Notorious B.I.G. That’s a typo. That’s a hip-hop joke. I don’t expect you to get it, Dr. Polkinghorne.

In any case, the Reverend Dr. John Polkinghorne comes to us from Cambridge University, England. He is a fellow of the Royal Society; a fellow and former president of Queens College, Cambridge; and Canon Theologian of Liverpool Cathedral.

Dr. Polkinghorne is married to Ruth Polkinghorne. They have three children: Peter, Isabelle, and Michael. Dr. Polkinghorne’s distinguished career as a physicist began at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied under Dirac and others. He became a professor at Cambridge in 1968. In 1974, he was elected fellow of the Royal Society. During that time he published many papers on theoretical, elementary particle physics in learned journals. If it sounds as if I know what I am talking about, I just want to say I got a 1 on my AP physics exam. That is not a good score.

In 1979, Dr. Polkinghorne resigned his professorship to train for the Anglican priesthood. He served as curate in Cambridge and Bristol, and was vicar of Blean from 1984 through 1986.

In 1986, he was appointed fellow, dean, and chaplain at Trinity Hall, Cambridge. In 1989, he was appointed president of Queens College, Cambridge. His own words in reaction to this honor from his official bio: “You could have knocked me over with a feather.” That is actually in the bio. You can go online and look that up.

I have to say that I’m surprised that particularly as a top physicist, Dr. Polkinghorne would have been so naive as to believe that someone might have actually knocked him over with a feather— even a very, very, very large feather. One from an emu or ostrich, perhaps, would hardly be able to knock over an average-sized adult male, even if he were temporarily stunned by his appointment to the presidency of a Cambridge college. As I say, even I, as a non-physicist, who got a 1 on his AP exam, know that, and I am embarrassed to report that Dr. Polkinghorne, with all his fancy degrees and honors, somehow did not know that.

Given Dr. Polkinghorne’s weight and any reasonable μ [“mu”] friction coefficient, I think the idea of his being knocked over by a feather is patently and demonstrably absurd. But I’m sure that by now, he has repented of the statement.

In any case, Dr. Polkinghorne retired as president of Queens College in 1996. He is a member of the General Synod of the Church of England and of the Medical Ethics Committee of the British Medical Association.

He was appointed KBE— Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire— in 1997. Now, a word to the wise: I am told that like many knights, Sir John is handy with a broadax, and if you aren’t in full agreement with his talk tonight, he might very well be forced to smite you or cleave you, as the case may be.

As most of us know, Dr. Polkinghorne has published a series of remarkable books on the compatibility of religion and science. These began with The Way the World Is. He said, “It was what I would have liked to have said to my scientific colleagues who couldn’t understand why I was being ordained.” The Way the World Is is available on our book table. It’s a fabulous book.

Just last year, Dr. Polkinghorne won the prestigious— very prestigious— Templeton Prize for progress in religion. The award has previously been awarded to such figures as Mother Teresa and Alexander Solzhenitsyn. Contrary to popular belief, it has never been awarded to Sir Elton John or to Sting. Glad to clear that up for some of you.

So, let me say then what a pleasure it is now to welcome to this podium at Socrates in the City— Sir John Polkinghorne.