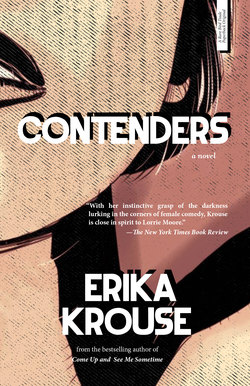

Читать книгу Contenders - Erika Krouse - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDong Haichuan was born in China in the early 1800s. The youngest son of the youngest wife, he was the bullied runt in his family hierarchy. He left home as soon as he could.

At a place called Crouching Tiger Mountain, Dong Haichuan spied a broken-down temple. He tried to cross the river to get there, but the current was too ferocious. He was stuck. Just then, two monks approached and crossed the river as easily as if they were walking across a bridge. He asked them for help. They carried him across the water, lodged him, and taught him martial arts for almost two decades.

When he crossed the river again eighteen years later, trouble returned. Fighters fight, and Dong Haichuan, now thirty-six, was now the best fighter in China. He killed someone, which created vendettas, and more killings. Things got complicated, but nobody could touch him. Dong Haichuan was a wanted man, an uncatchable criminal.

Finally, the Imperial Court offered him a deal. They would clear his record and give him a job collecting taxes. He would teach martial arts to royals, and live in the Forbidden City. The catch was, he had to be castrated.

Many boys and men decided to become eunuchs at that time. There was good money in it. Only castrated males were allowed to live inside the Forbidden City. Life there was preferable to life outside, where you could be killed or beaten for no reason, by people just like him. Outside, open sewers tunneled the sides of the roads. Inside the Forbidden City, all was peaceful, even if you couldn’t hold your urine.

Dong Haichuan took the deal.

After he recovered, he worked for the Courts. Then, with his top student Yin Fu, he traveled north. He extorted taxes from tyrannical authorities in the outer reaches of Manchuria, fought off bandits, traversed the Chinese countryside, and had a great old time. He was still beating people up. He was still undefeated. He was still doing the same things as before—roaming around, fighting, stealing, and killing people. But now he was a cop.

~

Punching her duffel bag in the early morning alley, Nina worried about the downturn in violent crime. Summer was usually her most lucrative time, when people loitered outside, drunk and angry at global warming. She socked away enough money to see her through the cold and snow season, when she often found herself shoplifting to eat, taking the odd factory shift, and ignoring increasingly urgent telephone calls from her landlord until summer’s cash rained down again.

But this summer, everything was backasswards. Nina blamed the economy. She blamed psychotherapy. She blamed Oprah. She blamed herself. All she had to look forward to was yet another meal of lunchmeat and bananas, when this was the time of year for king crab and gourmet potato chips. Was this what happened in normal careers?

She gave the heavy bag an extra-hard punch, and stopped to adjust the sweaty tape over her knuckles. A staph infection had taught her to protect herself from her own gear, especially this bag, which was probably alive with bacteria, MRSA, tetanus, and hantavirus. She had split it open so many times it was, by now, constructed almost entirely of duct tape. The sand had settled to the bottom, where it felt like she was kicking solid rock, and the damp insides added to the weight.

Still, there was joy in it. She punched it for another twenty minutes, snaked her belt around the railing overhead, and began a set of pull-ups. The walls were beginning to collect the day’s heat, which enveloped her body like a shell. Sweat was in her eyes when she heard from below, “Hiya.”

She dropped down, panting. Nobody ever came into her alley, and definitely not at seven in the morning. She wrapped the end of the belt around her hand, staring at the man, who was standing alone in a wife beater and jeans, with a holster at his side.

His smile sagged. “You don’t even remember me?”

Nina squinted, never good at faces. This guy was huge and blond and bristly, with a boxer’s stooped shoulders. His eyes were so pale they matched the glare from the clouds. Acne as a teenager, but now he was coming up on thirty. He had plucked his white unibrow into two distinct eyebrows, but they were already growing back into each other, like twins conjoining. His nose had been broken until the cartilage was crushed smooth. Both of his ears had transmogrified into a permanent state of cauliflower. And, of course, there was that gun.

Nina’s right foot slid back automatically, but the man seemed too clean to be a threat. She decided to slip past him, but he sidestepped, blocking her path. He grinned, but what his mouth was doing was disconnected from the blank expression in his eyes. “So, you punched me in the face.” He pointed at his left cheekbone, which looked the same as the other one.

Now she remembered him. Months ago in a bar, he had reached for her breast, like it was his beer mug. She felled him, slipped his wallet out of his pocket, and ran out the back door. In her car, she opened the wallet to discover it had a police badge in it. The thing scared her so much she ran home and threw it into the depths of her desk drawer without looking at it again.

So she was finally going to jail. Confused by her own feelings of relief, she stretched her wrists out.

“I’m not going to arrest you.” His voice was pleasant and sonorous, as if it had picked up momentum on its way from the inside to the outside.

Was he going to shoot her instead? Nina put her hands in the air. She wondered if she should run. But this cop just retucked his wife beater into his jeans and smiled. The holster remained snapped and untouched. Nina dropped her arms and pulled a cigarette from her shirt pocket.

“Filthy habit,” the cop said. “Have you ever seen the inside of a smoker’s lung?”

“How would I see that?” Lighting her cigarette, Nina glanced at him. “You’re really not going to arrest me?”

His smile vanished so quickly she saw it had been fake. “Give me my badge back.”

“I left you your gun,” she said. “You still have your gun.”

“I want the badge.” He didn’t say “need.” He smiled again.

“If you had been in uniform, I would never have hit you,” she said.

“Oh, that. I’m a detective. It’s like, business casual.”

“Get your boss to give you a new badge.”

The cop laughed.

“You can probably get a counterfeit one on Colfax for fifty bucks,” she said.

“I already did. Thanks. But I can’t have my badge in the wind. It’s traceable to me.” When Nina shrugged, he asked with unnerving gentleness, “Do you even know who I am?”

“You’re the cop I…from a few weeks ago, right?”

“I’m also Cage Callahan.” He grew an inch, but his shoulders slumped. “Maybe you saw me fight on TV about eleven years ago? MMA?”

“I don’t have a TV.” Nina blew out a clotted stream of smoke. “Is Cage your nickname?”

“What?”

“Don’t you guys all have nicknames?”

“Oh. No. It’s ‘Killer.’ Cage ‘Killer’ Callahan.” He half-shrugged. “A fighter retired right before my debut. So ‘Killer’ became available.”

Nina remembered how he fell on her first punch, like a diving falcon.

Cage’s upper lip tightened into a ridged line, transforming his fleshy face into a hard thing. “You caught me off guard. And I was hammered.”

She tried again to mount the stairs, but this time Cage swung his whole body in front of her. The charge radiating from his skin was vaguely acrid. The white hairs on his arms glinted, and hers stood up. His skin smelled strong, like Lysol. She sneezed, and then twice more.

The smile worked its way off Cage’s face. He snarled and “Bless you” wrested itself from his florid lips. Then he said it twice more, “Bless you bless you,” his face etched with despair.

That was interesting.

Nina squinted at the glare from his immaculate sneakers. The cuffs of his jeans were ironed. His perfect shave shone in the sunlight. A drop of sweat appeared on his brow, and he pulled a plastic pack of tissues from his pocket, picked one out, and dabbed at his face with quick motions.

And she thought she had seen everything. “I never met a fighter with OCD before. Or a cop, for that matter.”

Now that he was all cleaned up, Cage’s ever-present smile was back. “It’s a mild case.”

“It must be. Blood and murder and all that.”

“I work in the Robbery Unit.” At Nina’s face, Cage said, “The irony is not lost on me.”

“What’s it like, going from fighting to crime fighting?”

“Oh, it’s fine. Like being a garbage man, except the trash is human. Better than being a junkie, anyway.”

Nina agreed. Then she realized he was talking about her. “I’m not a junkie.”

“Then why rob people?”

She flicked ash. “We can’t all be cops. The world needs robbers, too, or there’s no game.” Apart from their guns, she wasn’t afraid of cops themselves. The only real difference between a cop and a criminal was one bad day.

Cage said, “Your casual demeanor with me is interesting.”

“You already told me you weren’t going to arrest me.”

“No. But.” Cage leaned against the wall and sighed. “The thing is, there are rumors now.”

“What rumors?”

“That I’m a tomato can and got knocked out by a bitch,” he said pleasantly. “The night I met you, remember the people I was with?” Nina did. They had cheered. Cage said, “You hit me in front of the VP of Talent Relations for the biggest fight promotion company in the world. He poured a beer on my face to wake me up. That’s not the kind of thing Antonio Ricardo Ricardito Gino Joseppe Irving Spina forgets.”

“Who?”

“Antonio Ricardo Ricardito Gino Joseppe Irving Spina? The biggest fight matchmaker on the planet?” He shook his head at her blank look. “We were discussing my comeback.”

People are always better in their imaginations, Nina thought. Cage might think he was just on a bad streak, but Nina could see his future, and it didn’t hold a comeback. His eyelids puffed at the corners from occasional dabbling in whatever—confiscated drugs, veganism, urine drinking, creatine, condomed hooker sex. His skin was ruddy and bloated, as if it held too much sour blood and steroids for his body to effectively contain. He was flaming out. The rough terrain of his face was flushed bright with the changing season, summer to autumn, but he was going out in a quieter blaze than he had anticipated.

Cage said, “I’m asking nicely.”

It was a reasonable request. She should give the badge to him, make a friend.

But if he had his badge back, he would then be free to arrest her. She’d be nothing to worry about. Now, she was a nothing with a stolen police badge. Jackson used to say, “It’s not strength—it’s leverage. Grab a pinky finger and you can move an entire man.”

“It’s in an undisclosed location,” she said. “Not hard to find, but not easy, either. If something happened to me, it would certainly pop up. But until then, it’s perfectly safe.” This was all a lie—the badge was in her desk drawer at home.

Cage probed her face with his washed-out gaze. “Tell you what. Why don’t we fight for it? Nina.”

Her breath caught. “How do you know my name?”

“I’m a detective, dumbass.” He smiled above Nina’s head. “You know, I’ve never been in this alley until today. This place feels…exempt.”

She knew what he meant. It was in-between. The oil slicks were more variegated, the bricks held more contrast, and the smog cleared away, just here, as if this particular alley had its own source of air and light.

Nina didn’t like Cage in her alley. “I’m not part of your story,” she said.

“Just fight me, chica. If I win, I get the wallet. If I lose, it’s yours.”

“It’s already mine.” And I already beat you, she thought. “I fight for money. Not hate, or whatever this is.”

“I’m not sure if I hate you or love you.”

Saying the word “love,” Cage suddenly looked bigger, handsomer. He stood tall, relaxed, his eyes clear. His shoulders were big enough for her to rest her head on, without him even feeling the weight. He was a police officer. He was a smiling keeper of secrets, an armed person in an unarmed world. Could she rest there in his Lysol cloud? Or anywhere?

“This is already an unhealthy relationship,” she said. When she lit another cigarette, her hand shook. Summer buzzed against her skin, itchy.

Cage stepped closer, looked in either direction, and kissed her.

His kiss was matter-of-fact, a prerequisite, like taking your pants off before sex. Nina tried to lean into him, but couldn’t find her angle into his enormous body. She touched his cheek, and it slid from her fingers.

Cage disengaged from her mouth with a soft pop. He plucked the cigarette from her hand with perfectly groomed fingernails. Then he turned his back on her to stub it on the wall behind him.

Nina decided to choke him out.

She grabbed Cage’s big shoulders for leverage, hopped up and jabbed both feet into the hollows of his knees. They buckled. The air sharpened as he thudded to a kneel.

The cigarette fell from his fingers. Before it touched the ground, she had already launched off the ground again onto his back, piggyback style. She locked her feet around his waist. He was already twisting toward her, a giant boa constrictor. Sweat had sprung to his skin, lubricating Nina’s rear naked choke as she snaked her arm around his neck.

The sun poked Nina in the eye. Cage’s Adam’s apple chugged against the soft crook of her inner elbow. Realizing what had just happened, he yanked at her arms, but her other hand was already shelved against his head. He clawed backward at her face. She buried her face in his neck. He smelled of dandruff shampoo, expensive aftershave, and the kind of cheese you don’t have to refrigerate. She was wondering what his diet was like when he whirled around and thrust himself backward against the wall.

“Oof,” she said, sandwiched between brick wall and high-velocity Cage. Something happened to her ribs, her hip. But she held on.

He did it again, but she tucked her chin and braced for the impact. It came, harder than before, and she held on. She always held on.

Cage reached for his pocket holster, but his arm was slow, limp. He fumbled with the snap. By then, his head must have felt like a grape, about to pop out of its skin. The tiger tattoo on his flailing shoulder roared, retracted, slept. His body sagged downward. The gun rested, cupped in his hand. He relaxed in her arms. Whites lined the cracks of his partly-shut eyes.

Nina laid Cage down flat in the dry, hot street. She checked his sluggish pulse, his hot, wet breath on the back of her hand. She picked up the gun. It was so heavy. She caressed it for a second, then threw it in the dumpster. Washed in adrenaline, she climbed the fire escape to her apartment.

Nina didn’t feel bad about what she had done. She felt as neutral as a bowl of water on a ledge. She was just showing him. Nobody really loves anyone, not really. It wasn’t a constant, or a quality. The truth as Nina knew it: when your life is on its thin edge and you’re on your last breath, you only have enough room in your heart to love one thing. Air.

~

Isaac dropped the photograph and postcard onto the dashboard of the rental car, and Kate immediately snatched them both up. The postcard featured a movie still of Ronald Reagan tucking a chimpanzee into bed. It was from the film, Bedtime for Bonzo. The printed handwriting on the other side read: “Dear Nina. I am sorry about your tooth. I have a house here with an extra bedroom for you, and I turned my basement into a dojo. I will wait. Jackson.” It was followed by an address, no phone number.

Kate put the postcard in her overalls pocket before pulling it out again to read it.

“Your hand’s sweaty,” Isaac said. “You’ll smear the ink.”

“Who is this man again?” she asked.

“Ronald Reagan. Ex-President of the United States.”

Kate examined the card. Then, “No, the person who wrote on it.”

“He was your aunt’s teacher.”

“Was he your teacher? Or daddy’s?”

“No. I saw him occasionally, and Chris wasn’t interested in karate. Nina mentioned him a little, when she talked at all. Which was never.”

“Karate, like karate chops?”

“Yeah.”

Kate karate chopped the dashboard. She karate chopped Isaac’s arm. She karate chopped her bagel, which was already stale in the dry Colorado air. She flipped the postcard over. “The President of the United States was the daddy of a chimpanzee?”

“No, Kate. He was acting. It was fake.”

“Like you?”

Irritated, he said, “Like his presidency.” Then he realized that she had been talking about his acting. Not about his fakeness.

She studied the picture up close until she was cross-eyed. “Shouldn’t you be nice to him?”

“Ronald Reagan? He’s dead, honey,” Isaac said, and instantly regretted it. “He had Alzheimer’s disease, and bankrupted our country. His presidency led to George Bush’s presidency, which led to George W. Bush’s presidency, and the only good thing I can say about that is that I got to reuse my ‘Impeach Bush’ bumper stickers until I sold my Jeep, and they probably increased the value.” He looked at Kate, whose mouth was open.

“You’re weird,” she said.

Isaac wondered if Nina even knew that her brother had been sick, was dead. AIDS is such an isolating disease, but even before that, Nina had been excised from Chris’s life so completely, her silhouette remained in the space left behind.

So why did Chris will Kate over to a ghost? Isaac glanced at the little girl, who was narrating the sights of Denver to No-Hair. “This is a gas station,” she whispered. “This is some dirt.” Her legs were strewn about the seat like a couple of Pick-Up Sticks. Shadows encircled her eyes. She still wasn’t sleeping.

“If we don’t find her this time, we can come back again, right?” Kate pushed and pulled on the automatic door lock button. The doors made a chunk! noise over and over.

“Stop playing with the car.”

“Why?” She chunk!-ed it one more time.

“Kate,” slow, rising. But at least she wasn’t whispering and cowering, which, frankly, got on Isaac’s nerves.

“Why don’t we just look her up in the phone book?” she asked.

“She’s unlisted. Or, she doesn’t have a phone.”

“Everybody has a phone,” she whispered to No-Hair. She started licking her hands and smoothing down her own hair like a cat, straightening her overalls. She pulled down the visor mirror. She pinched her cheeks and bit her lips to make them red. “Why don’t we look back in your old town?”

“Grand Junction?” Isaac tasted dirt, the way he always did when he thought of his hometown and 28½ Road.

It took until Isaac’s adulthood to realize that normal towns don’t have fractions in their streets. 28½ Road is exactly twenty-eight and a half miles from the Utah border. There is also 295/8 Road, 30¼ Road, and so on. He always thought that if Grand Junction had a motto, it would be, “We’re Not Utah.” But it looked like Utah—stenciled with canyons, dry as alum. The valley was made of sawdust and petals, sunshine and frost. Despite the heat and thirst, in Isaac’s day, there was a feeling of imminent prosperity in the air. See, there was oil in them there hills.

It’s hard to imagine prehistoric whales and dinos swimming above Colorado’s snowcapped peaks, but it’s also hard to imagine that humans would come to burn the remains of these gargantuan animals in Kia Rios. When the prehistoric sea retreated, the lagoons filled with peat, coal, sand, and dinosaur corpses. This witches’ brew turned into oil shale, which rose like bread and turned into the Colorado Rockies.

It wasn’t until the 1970s that a hundred million years of causes and effects presented a one-time solution for the oil crisis. Exxon moved into the Western Slope with the objective of mining petroleum from what the Ute tribe used to call “the rock that burns.” The plan was simple: strip mine the hills, and squeeze serviceable oil from the shale.

Grand Junction grew big. Then oil prices retreated in the early eighties. Oil shale was more trouble than it was worth. On a day locals called “Black Sunday,” Exxon laid off their employees and skipped town.

Over the next year, Grand Junction dwindled to a third of its size, as people moved away to wherever there might be jobs. Home values halved. Partially-built office buildings sat fallow on their foundations. Banks sued, frantic. Schools sank into disrepair. Grand Junction turned into Grand Junkyard, and stayed that way for over a decade. Even after the town finally recovered, the Black family didn’t.

The problem with poverty is that there’s nothing to do except beat your children. Isaac remembered Chris’s black eyes, the finger bruises on Nina’s arms. There was no way to explain any of this to Kate. “Nina would never go back there,” he said.

The address on the postcard led them to a yellow ranch-style home with purple petunias in front. As soon as they knocked, an older man poked his head out the door. Three feet below him, a beagle poked out his head, too.

The man was short and compact. He wore a faded, tight-fitting Hawaiian shirt and dress pants. His sparse hair was dyed a startling shade of black, the kind that absorbs light instead of reflecting it. He was Caucasian, with a perma-tan that had faded to a mottled yellow. His skin had an astounding number of wrinkles, like a piece of paper that had been repeatedly crumpled and smoothed out again. Isaac couldn’t remember Jackson’s face before, but he now recognized him immediately. The dog sniffed the air.

“Hi,” Isaac stuttered, “Mr. Jackson. I-I was wondering if, ah. Um.”

“I don’t believe in your God,” Jackson said and began to shut the door.

“No, I’m not—it’s Nina, I’m looking for Nina. Sorry to intrude. Mr. Jackson, please.” He snatched the postcard from Kate’s hand and stuck it through the narrowing crack in the door.

Jackson picked the postcard from Isaac’s outstretched hand. It took him so long to read it, Isaac wondered if he hadn’t written it after all, or if he could, in fact, read.

Finally, Jackson waved the card in the air. “How did you get this?”

“Chris had it. Her brother. She had already left by the time it came to their house. I know it was a long time ago, Mr. Jackson, but we were hoping you might know where she is.”

“Just Jackson. It’s my first name.” Jackson motioned them inside.

Isaac felt oversized inside the low-ceilinged house with its geriatric smells. The beagle thwacked his tail against the legs of the furniture. He crouched on the carpet and began peeing.

“No! Hank! Stop it!” Jackson shook the dog by his collar with a surprising strength. The dog stopped peeing, eyes round. Jackson threw a dishtowel over the spot and stepped on it with his slipper. “Submissive urination. He pees like a girl when he sees visitors. It’s embarrassing.” Jackson had a singsongy, truncated way of speaking, like he was distracted by the beat of a song in his head. His yellow shirt was tucked into his khaki pants so smoothly, his outfit almost looked like a bodysuit. Every remaining hair on his head was in place. Nina had said that he had gotten blown up in Vietnam. She said that he had killed twelve men with his hands. It was hard to believe from this man with a potbelly and freckles on his bald spot.

Kate held out her hand to the beagle, who tongued it. Jackson pointed at a distended couch. They sat on it and were instantly enveloped. It smelled like wet dog and old scrambled eggs. Jackson scrubbed at the pee spot on the floor and sprayed half a can of deodorant on it, and then the house smelled like deodorant, too.

“Now, then.” Jackson finally sat on a folding chair. His mouth was an upside-down crescent moon. “Nina left her daughter behind?”

“Kate is Nina’s niece,” Isaac explained. “Chris’s daughter. I’m Isaac.”

Jackson looked so relieved, Isaac thought he was going to pee on the carpet himself. Jackson studied Kate, who squirmed under the weight of his gaze.

“Stop looking at me,” she whispered.

“Kate!”

“That’s okay,” Jackson said. “I think I have something to eat.” He trudged into the kitchen, Hank licking his leg all the way across the apartment.

Left alone, Kate got up to study the framed cross-stitch picture of a cowboy riding a horse. She poked her finger in the empty candy dishes.

Jackson padded back in, bearing a tray with coffee cups and a chipped plate with little round, flattish balls on it. He set the plate on the table. Cornstarch trembled on his fingers as he poured green tea.

Kate climbed into a chair, waggled her legs, and grabbed one of the round balls from the plate. She sniffed it and studied it at close range until her eyes crossed. She bit into it.

“Squishy,” she said, mouth full. “What is it?”

“Omochi,” Jackson said.

She squinted at the smooth, white cake before taking another minibite. “What’s inside? Chocolate?”

“Red bean paste,” Jackson said.

Carefully and immediately, she placed it down on the coffee table.

Isaac smiled at the old man, who didn’t smile back. “I was friends with the Black kids,” he said. “I remember seeing you with Nina sometimes. Do you still teach?”

“No. I quit karate. I’m retired,” Jackson said.

“You seem young for retirement.”

“I’m sixty-three. I get a VA pension.”

Isaac lied, “You look much younger. What do you do now?”

The lines in Jackson’s face multiplied. “This and that.”

“Do you still practice Chinese medicine?”

“Here and there.”

Kate said, “I know a girl in my school who’s allergic to her own spit.”

“What happens to her?” Jackson asked.

“Her mouth swells up.”

“That sounds uncomfortable,” Jackson said.

“She uses special toothpaste.”

Jackson wiped something invisible on his pants. “So.”

“Yeah. Okay.” Isaac sat up. “We’re looking for Nina. Her brother died.”

Jackson’s face elongated, his creases sharpening. “I’m very sorry to hear it. He was a nice boy.” He looked at Kate. “Your father died, then.”

“He died in the hospital,” Kate said.

“You were there?” he asked. “With him?”

She nodded.

“It wasn’t your fault,” he said.

Kate’s eyes grew wet, and then dried instantly in the arid air. She tugged at her sleeves, wiped her nose, stared at the dog.

Isaac leaned back, exhausted by his own failure. How did Jackson understand Kate better than Isaac did, after just a few minutes?

“How do you fit in?” Jackson asked him, sipping from his cup. “You’re taking care of her?” He nodded at Kate.

“I have power of attorney over her, but not guardianship. That’s supposed to go to Nina, wherever she is. I’ve had the power of attorney for two years, but it expires in about a month. Chris didn’t think he’d last that—” he glanced at Kate. “We all want this thing to be settled.” Isaac realized that he had just called Kate a “thing.” “This…custody matter.”

Everyone drank their tea.

In the silence, Hank started biting at his leg, and licking it over and over. Kate asked, “Why is he doing that?”

“The same reason dogs do everything. Because it feels good, smells good, tastes good.” Jackson looked wise then, a doctor of obscure medicines. Isaac rested his bleary eyes on Jackson’s still form. I want to be a dog, he thought. I want to be his dog. Isaac understood why Nina spent so much time with this man. He was sinking lower into the man-eating couch. He wanted to lie down and sleep for a hundred years among the yellowing lead paint and bean paste.

Jackson said, “I don’t know where Nina is. I haven’t seen her since I left Junction. We had a fight.”

“About what?”

Jackson drank his tea. Kate kicked the chair harder and harder.

“You knew their mother, right? Before she vanished into the ether,” Isaac said.

“Not the ether. Tokyo.”

“You knew where she was?”

“I gave her the money for the ticket.”

Something curled up inside Isaac. “You what?” After his mother left, Chris slept in Isaac’s cluttered basement for days, peeing in cups and leaving them on the stairs for Isaac to empty. Nina stared for hours and hours at the sheets on the clotheslines. “Why?”

“She wanted to go.”

“She had children! How could you?” Isaac was now yelling, yelling at a man in his own home.

“I didn’t want her to do the things that desperate Asian women do.”

“What? Something terrible, like stay and raise her family?”

“Ritual suicide.”

Isaac’s jaws flapped open, then shut. “Oh.” His gaze hooked on a photo tucked into a mirror. It was the same one he had brought from LA, of the three of them. Isaac leaned over and pointed at his image with his thumb. “That’s me. In the middle.”

“I know.”

The refrigerator hummed.

Jackson said, “You like to talk about yourself, don’t you?”

Isaac cleared his throat. “Did, uh, Nina ever contact you after your falling out?”

“It wasn’t a falling out. It was a fight.”

“You didn’t try to find her again? After you wrote this postcard?” Isaac picked it up off the coffee table and waved it in the air. He felt oddly invisible.

Jackson leaned back in his folding chair and glanced at the clock on the wall.

Kate tugged at Isaac’s shirt, but he ignored her. “I mean, you were best friends. You were her only friend.” Isaac opened his palms. “So you have no idea where she is. Or why, in twelve years, she never once looked you up.”

“I don’t know why!” Jackson suddenly shouted, his Hawaiian accent thickening. Kate shrank in her seat. “Sometimes people leave! Sometimes you leave, too, and nobody knows where anybody’s going, and just like that, you lose them forever! This is America! It happens all the time!” Jackson popped up and clenched his hands into gnarled fists. Isaac’s stomach contracted. He didn’t want to be Jackson’s dog anymore.

“I lost my friends, too! I lost everyone in my unit! You’re asking me why?” The old man loomed, sweating. “Do you still keep track of everyone you once knew? Everyone you loved? Your favorite teacher? How about your first girlfriend?”

“No, sir.”

“No! Sir! She’s gone, or dead, and you don’t know ‘why’ either! Huh!” Standing in profile, Jackson downed his tea, his throat chugging. Isaac held his own scalding cup in his shaking hand, wondering how the man could drink it like that without burning his throat.

He and Kate jumped again when Jackson slammed his empty cup down on the coffee table. A ceramic chip flew into the wall. Jackson pointed a crooked finger at Isaac’s face. “You find Nina? Send her to me. I mean it. Or I’ll find you.” Jackson gave Kate a look Isaac didn’t understand, and then stomped to the back of the house.

To hide his shaking lips, Isaac sipped the bitter tea.

After a minute, Kate whispered, “Is he coming back?”

After another minute, Isaac called out, “Mr., um, Jackson?” and then, “Sir?” He waited one second, two, before snatching the postcard and photograph from the coffee table.

Kate stared at the half-eaten rice cake on the table, picked it up, and put it in her pocket. She whispered toward the open door, “Thank you for the…thing.”

They crept out.

As they drove away, Kate said, “You blew it.”