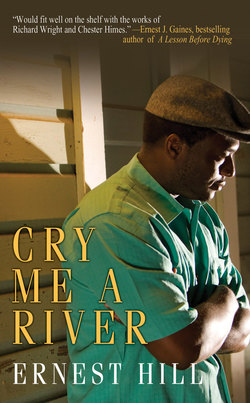

Читать книгу Cry Me A River - Ernest Hill - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 9

ОглавлениеAfter leaving the prison, Tyrone drove back to Brownsville with a staunch determination to know the man whose charge it had been to save his son’s life and to rid himself of the nagging questions gnawing deep within his troubled soul. There was in him the feeling that the contest for his son’s life had not been a battle in which Captain Jack had fought to win, but a game in which Captain Jack had played not to lose. There had been no knights, or pawns, or kings or queens, but there had been talk of deals, struck between friends, in quaint little rooms, over cordial glasses of brandy or stiff shots of gin.

When he pushed through the door of Captain Jack’s office, Janell was sitting behind the desk up front, with her head bowed and her arms folded before her. There was a cup of coffee on one corner of her desk, several large books on the other, and an open file lying before her. Their eyes met. She smiled at him, and he approached the desk, ever aware of the lingering scent of her perfume in the cool, dry air.

“Can I see Mr. Johnson again?” he asked.

“I’m sorry, he’s out of the office until tomorrow,” she said. “Can I help you with something?”

Tyrone hesitated before answering. He had looked at her earlier, but he had not seen her. She was tall, five-seven or five-eight. That, he had noticed before. But he had not noticed her straight white teeth, or her big, beautiful brown eyes, or her long black hair that was pulled back and clamped behind her head, exposing her high cheekbones and her smooth brown skin. He had noticed her professional demeanor, but not the exquisite manner in which she dressed. She wore a navy blue skirt, a matching jacket, and a white shell. Her nails were sculptured and finished in a French manicure. She did not slouch, but sat tall with her back straight and her shoulders erect. She had a thin herringbone chain about her neck and two tiny gold studs in her ears. Her fingers were bare save for the single pearl that she wore on the ring finger of her right hand.

“I was here earlier,” he said. “I’m—”

“Marcus’s father,” she interrupted. “I remember.”

Tyrone nodded but did not speak.

“What can I do for you?” she asked.

Her question caught him off guard. He had not anticipated Captain Jack being away from the office; therefore, he had not anticipated a conversation with her. There was a window to his right. Through the window loomed a gas station. A pig farmer had pulled a truck and a trailer filled with hogs next to one of the pumps and was filling his truck with gas. Tyrone was looking at the oversized man, who was adorned in overalls and wearing a big cowboy hat, when the man set the nozzle back in place and screwed the cap back on the gas tank, but he was not seeing him. He was collecting his thoughts; he was formulating his next question.

“Did you work on my son’s case?” he asked after a brief silence.

“Well, yes and no,” she said. “I was not working here when his case was tried, but I did work on his appeal.”

“Then, you’re familiar with the case?”

“Very,” she said. “Why do you ask?”

Tyrone glanced at her, then looked away. Her desk was in the corner on the left side of the room. It was too large for the space and had been turned catercorner with one end extending to the far wall and the other to the door leading into Captain Jack’s office. There was a couch and a few chairs on the right side of the room, next to the window. A plain, wooden coffee table that had been covered with several rows of neatly arranged magazines sat in front of the couch. There was no television, but there was a small radio atop her desk. It was on low, so low, in fact, that it was barely audible.

“Who hired Mr. Johnson?” he asked bluntly.

“Marcus’s grandfather,” she said, seemingly confused by the question. “Why?”

Tyrone paused again and measured his words. He didn’t want to say the wrong thing. He didn’t want to offend her.

“I heard the governor has given his assurance that my son will die.”

“Given assurance to whom?” she asked, her tone indicating shock.

“The victim’s relatives.”

“I don’t believe that.”

“That’s what I heard,” Tyrone said, looking deep into her eyes.

“That’s unlikely.”

“But is it possible?”

“Yes,” she said. “It’s possible.”

“Is it legal?”

“It’s legal.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Sir, both sides have a right to argue their case before the governor,” she explained. “He can listen, if he chooses, but he is not obligated. Ultimately, it’s his decision.”

“How well do you know these people?”

“What people?” she asked.

“The governor … Mike Buehler … the girl?”

“Not well,” she said. “I’m not from around here.”

“Where you from?”

“Monroe,” she said.

“That’s a long ways from Brownsville,” he said. “How in the world did you find a job way over here?”

“There was a job bulletin posted at the law school for a part-time paralegal. It seemed interesting, and since I’ve always wanted to practice law in a small town, I decided to give it a try. I called Mr. Johnson, he hired me, and I’ve been here ever since.”

“You a student!”

“Yes, sir.”

“You ain’t a real lawyer?”

“No, sir, not yet. I’m a third-year law student.”

There was silence.

“How well do you know Mr. Johnson?”

“Excuse me!” she said, probably louder than she had intended. Tyrone hesitated. She was black like him, but how honest was she? Could he speak to her freely? Would she be forthright?

“Why did he ask my son to cop a plea?”

“Have you ever tried a capital case?” Hers was a rhetorical question that required no answer. “Do you know what it’s like to have somebody’s life in your hands? Yes, he advised Marcus to plea. But his motives were not sinister, as you seem to be implying; he was simply trying to save your son’s life.”

“But he didn’t try to get him off, did he?”

“The town was in an uproar.”

“So, he sold him out?”

“He fought for your son’s life,” she said. “I’ve watched him sleep in this office for days at a time, looking for an angle, or a mistake, or anything to save Marcus. And he’s still looking.”

“Looks to me like he’s done gave up.”

“He’s doing everything he can.”

“Do you really believe that?”

“Yes, sir, I do.”

“Would you feel the same way if Marcus was your son?”

“Yes, I would,” she said, looking at him with stern eyes. “Let me tell you something about the man whose character you are questioning.”

“No,” Tyrone interrupted her. “Let me tell you something about the person they trying to kill. I was hard, but not my son. I stayed in trouble, but not him. He was always a good kid. A do-gooder. A mama’s boy … Yesterday, a friend of mine tried to convince me that he has changed, but I know better.” He paused. “Does he have a record?” he asked, then quickly added, “I mean, before all this happened?”

“No, sir,” she said. “But you know the prosecution’s response to that, don’t you?”

“No,” Tyrone said. “What?”

“They contend that his clean record does not mean that he has not done anything; it simply means that he had not been caught.”

“He ain’t done nothing,” Tyrone said emphatically. “Not Marcus. No way.”

“How can you be so sure?” she asked.

“Because I know him,” Tyrone told her. “When he was a little boy, I tried to change him … I tried to make him tough … I tried to make him mean. But no matter how hard I tried and no matter what I did, I couldn’t. He just stayed the same … wouldn’t hurt a fly.”

“Why did you want to change him?”

“Where exactly in Monroe do you live?”

“Castle Rock,” she said.

“What kind of place is that?”

“A quiet place. Peaceful.”

“Suburbs?” he asked.

“That’s right,” she said.

“Crime?”

“Not much.”

“Ever seen a rat?”

“Sir, what does that have to do with anything?”

“Everything!”

“Mr. Stokes, this is not about me.”

“You’re right,” he said. “It’s about my son, and me, and where we’re from.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Where we live, you have to be tough to survive. Get them before they get you. That’s what I tried to teach my boy. But he couldn’t learn it. It just wasn’t in him. That’s why I know he didn’t kill nobody. It ain’t in him. He couldn’t hurt a fly. It just ain’t in him.”

She looked at him but did not speak.

“Ma’am,” he said. “The state got my boy, and he running out of time. I just need somebody to tell me what to do.”

“He’s exhausted his appeals,” she explained.

“I understand that,” Tyrone said.

“We’ve petitioned the governor.”

“There has to be something else.”

“There is,” she said.

“What?” he asked.

“Prove he didn’t do it.”

“I want his file.”

“Yes, sir,” she said. “Come back in an hour.”