Читать книгу The Life and Death of Lord Erroll: The Truth Behind the Happy Valley Murder - Errol Trzebinski - Страница 10

4 To Hell with Husbands

Оглавление‘Come, come,’ said Tom’s father, ‘at your time of life,

There’s no longer excuse for thus playing the rake –

It is time you should think, boy, of taking a wife’ –

‘Why, so it is, father – whose wife shall I take?’

Thomas Moore

Whereas a weaker young man might have been unable to recover from the shame of having been removed from one of England’s finest schools, Joss’s disgrace appears to have had no effect on his confidence.1 If his parents were livid with him, they did not let it show publicly. They allowed his education to continue at home in Le Havre, the British Legation to Brussels’ wartime base. Lord Kilmarnock found a tutor for him, a man who before the war had worked at the University of Leipzig. Through him Joss brushed up his German, and according to fluent German-speakers he spoke the language extremely well, some even claimed ‘beautifully’.2 (In later life, without daily practice, his command of German weakened somewhat.) His French also benefited from his return to a francophone country.

In a press interview in the 1930s Joss said of his time in Le Havre, vaguely, that he had been ‘performing liaison work with the Belgians’. Perhaps his father had pulled strings to get him some practical experience of Foreign Office work and to broaden the narrow horizons of his studies at home. When Lord Kilmarnock moved on after the war Joss too was transferred to the British Legation in Copenhagen as an honorary attaché. Lord Kilmarnock acted as Chargé d’Affaires there until August 1919.3 Joss was eighteen by this time and, help from his father or no, he was beginning to gain some very valuable Foreign Office experience.

Meanwhile, Lord Kilmarnock was made a CMG in June 1919 and a Counsellor of Embassy in the diplomatic service three months later. His father’s impressive career was starting to awaken ambitions in Joss, for that same year he applied to sit the Foreign Office exam in London. Candidates were told to bring a protractor with them.* The result of this strange instruction was that on the morning of the exam, outside Burlington House, ‘a multitude of officers converged with protractors in their hands’.4

Since Joss had ‘one of the best brains of his time’ he sailed through his Foreign Office examination – no mean achievement. At the time the Foreign Office exam was considered to be ‘the top examination of all’. The Kilmarnocks must have been very relieved that their son appeared to be looking to his laurels at last. On the strength of his exam results Joss was given a posting, on 18 January 1920, as Private Secretary to HM Ambassador to Berlin for three years – ‘a critical post at a critical time’.5

Two days later he reported for duty at 70–71 Wilhelmstrasse, Berlin.

For a few months it transpired that Joss was working in the same embassy as his father: a week earlier, on 10 January, Lord Kilmarnock had been appointed to Berlin as Chargé d’Affaires, to prepare for the arrival of Britain’s new ambassador now that diplomatic relations with Germany were resuming. He was the first diplomat to be sent to Berlin after the Armistice. Having got his posting on the strength of his Foreign Office exam result Joss was probably somewhat non-plussed to appear still to be working under his father’s wing. However, Lord Kilmarnock was soon appointed Counsellor to the Inter-Allied Rhineland High Commission in Coblenz and in 1921 was made British High Commissioner. Lord and Lady Kilmarnock were to remain in Coblenz until his death.6

Joss stayed on in Berlin for the time being. He obviously enjoyed Teutonic company. He would later socialise with the German and Austrian settlers in Kenya, and he returned to Germany on a couple of visits to Europe in the 1920s and 1930s.

The British Ambassador in Berlin, Sir Edgar Vincent, 16th Baronet D’Abernon, was an Old Etonian; his wife, Lady Helen, was the daughter of the 1st Earl of Faversham. They were a charming couple of whom Joss was very fond. Under their auspices he would come into contact with a wide range of influential and up-and-coming personalities – figures such as Stresemann, Ribbentrop and Pétain, just three whose names would be familiar to everyone in Europe by the outbreak of the Second World War.7 The British Embassy stood only doors away from Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg’s Presidential Palace, which had once been occupied by ‘the Iron Chancellor’ Prince Otto von Bismarck and, in 1938, became Ribbentrop’s official residence as Foreign Minister to Adolf Hitler. Prior to that appointment, Ribbentrop was to be German Ambassador to London from 1936.

When Joss met him in 1920 Ribbentrop, six years his senior, had just recently been demobilised. He was a tall, fair-haired man who ‘held his head very high’, was very arrogant and ‘inaccessible’.8 He looked like a caricature of an English gentleman in a humorous magazine and ‘wore a bowler hat and carried an umbrella in spite of a cloudless sky’. At this time, Ribbentrop was ADC to the German peace delegation.9 Joachim von Ribbentrop and his wife Annlies worked extremely hard at penetrating the circle of Gustav Stresemann, a statesman of first rank who was briefly German Chancellor in 1923. D’Abernon and Stresemann were close and, after Joss left Germany, together instigated the Anglo-American Treaty and the Pact of Mutual Guarantee embodied in the Treaty of Locarno in 1924. Stresemann’s son, Wolfgang, recognised the social pushiness of the Ribbentrops and how they ‘even got into the British Ambassador’s functions’. The Ribbentrop networking technique was so effective that some of their hosts, ‘Lord D’Abernon included, were surprised to find themselves entertaining their brandy merchant’ – Annlies’s father.10

By contrast, Joss, who had no need to elevate himself socially, was an ideal candidate for D’Abernon’s needs at a sensitive time in Germany when constant communication between different countries was vital. D’Abernon was a fine diplomat with a wealth of experience. In him Joss found a man to emulate and, while he appeared to take a delight in outraging his father, he knuckled down under D’Abernon and never stepped out of line, respecting the Ambassador’s opinions on many governance matters. He also sought his views on historic battles, modern warfare, thoroughbred horses and champion tennis – subjects which were to be of continuing interest to Joss. D’Abernon’s informality endeared him to Joss and, in his friendship with the older man, he found his attention drawn to more serious aspects of life. D’Abernon had taken risks – successfully – with his own career, and Joss admired him for this adventurousness, a quality he shared. D’Abernon had at one stage been Chairman of the Royal Commission on Imperial Trade: this was to be the field that most impressed itself on Joss, whose understanding of it became almost as profound as his mentor’s. The conclusions that Joss reached at this time would enable him to argue, off the cuff, about reforms to the Congo Basin Treaties in Kenya a decade or so later. His liaison work in his capacity of Private Secretary to the Ambassador was honing his skill in retaining detail – he was becoming proficient at storing away information to use later, a habit which would pay off time after time.

In 1920 Joss accompanied his parents twice to the American Cemetery in Coblenz, in the Allied Rhineland; on 20 May they went to the Decoration Day service, then in November attended the Remembrance service. Standing on the dais, looking sombre, Joss was the youngest among dignitaries such as Monsieur Fournier, the Belgian Ambassador, Herr Delbrucke, the Austrian Ambassador, Monsieur Tirade, the French Ambassador, and Marshal Pétain. On each occasion he gazed down from the stand at the huge garden, and all that he could see stretching into the distance was row upon row of white military crosses. He would never forget this display of tragic waste.

Joss’s work involved a lot of travel from one European capital to another. Being based in the country of the vanquished provided him with a view of the war from both sides. He had witnessed the decimation of Eton’s sixth form, and Le Havre too had shown him a facet of war. Then there was the neutrality of Scandinavia: he discovered that there was also something to be learned from those who had stood back. The next three years were to provide ample time to listen to the experiences of the former enemy.

Joss’s dislike of bloodshed showed too in his reluctance to take part in blood sports. Some regarded his detachment with suspicion. According to Bettine Rundle, who knew Joss in those days, he was quite unpopular with Lord Kilmarnock’s staff on account of not joining in their hunting pursuits. However, he did play football regularly against teams formed by the various different Allied armies based in the area. Association football was particularly popular in the British Army, and on one occasion Joss captained the side that beat the American Army team.11 He was also a very experienced polo player by this stage.

Equally, his unpopularity with his father’s staff could have been due to jealousy; they probably resented his plum job at the Embassy and wrongly assumed he had got the post purely through his father’s influence.

Whatever feelings he inspired among embassy employees, Joss enjoyed great popularity in his social life and on his travels around the capitals of Europe. The temptations in the cities were plentiful, affording men opportunities for unrestrained pleasure – in this respect Joss was very much a player. In the society in which he had been raised, sexual mores for men were liberal. It was expected of Continental grand dukes and archdukes that they should seek to indulge their sexual fantasies with mistresses rather than their wives. During the late summer, the fashionable German spas turned into the hunting grounds of the most famous courtesans of Europe. By the standards of the day Joss did nothing that others did not do, and many indulged in far more excessive behaviour.

From 1919 onwards Joss paid regular visits to Paris, where he got to know a wealthy American socialite, Alice Silverthorne, with whom he enjoyed an intermittent affair. His girlfriends were usually blondes but Alice was dark and, also unlike the majority of his lovers, close to him in age. In 1923 she married a young French aristocrat, Frederic de Janzé. Alice was bewitchingly beautiful, rich, self-willed and neurotic. ‘Wide eyes so calm, short slick hair, full red lips, a body to desire … her cruelty and lascivious thoughts clutch the thick lips on close white teeth … No man will touch her exclusive soul, shadowy with memories, unstable, suicidal’ – this was her husband’s adoring and, ultimately, prophetic verdict.12 Alice was to become notorious as the Countess de Janzé, when she was tried for attempted murder in Paris in 1927. She had shot her lover Raymund de Trafford in the groin at the Gare du Nord. She married him five years later and they separated about three months after that. Alice and another beauty Kiki Preston – a Whitney by birth – were part of the American colony in Paris who welcomed Joss into their social circle.

The early twenties saw the Paris of Hemingway, Molyneux and Cecil Beaton.13 Joss thrived in this glamorous climate. Beaton’s photography drew the fashionable world’s attention to the beauties of the day. Joss would get to know most of them well. One of Beaton’s ‘finds’ was Paula Gellibrand, a ‘corn-coloured English girl’ who became one of his muses. When Paula and Joss first met, she was untitled and the daughter of a major who lived in Wales. Joss’s relationship with her would surface haphazardly at distant points on the globe since she would become the wife of no less than three of his friends and, being an inveterate traveller, would appear wherever the glamorous foregathered be it Paris, Venice, New York, London or Antibes. She was tall and languid, and according to Beaton, her ‘eyelids were like shiny tulip petals … [she was] the first living Modigliani I ever saw’.14 Ultimately Paula would happen up on Joss’s doorstep in the Rift Valley, married to Boy Long (whose real first name was Caswell), a rancher and another neighbour of Joss’s – by then Joss and Paula had been friends for fourteen years.

Once Joss disappeared into the wilds of Africa with his first wife Idina, another eccentric socialite in Paris – she and Alice fell for Joss, separately, at roughly the same time – Kiki Preston, Frédéric and Alice, among other friends, would flock after them. The clique which became infamous as the Happy Valley set was formed in France before any of them left for Africa.

History does not relate where Joss and Idina first met. It could have been in Paris, for Idina was there in 1919, mixing with a Bohemian set that would have appealed to Joss. It is possible that they had met in more conventional society even earlier, in Helsinki, when Joss was still living in Denmark, because Idina’s younger sister Avice was then living in Helsinki with her husband Major Sir Stewart Menzies, and Idina would have visited her there. Menzies was a military man but he usually established ambassadorial contact wherever he worked. When Joss was in his thirties, he would become head of the Secret Services.*

It is likely that Joss and Idina had been circling one another for at least eighteen months before their affair started. Idina was another of the beauties who caught Beaton’s imagination – he noticed the way she ‘dazzled’ people.15 Her red-gold hair was styled like a boy’s and, her bosom being too ample for the dictates of fashion, she flattened it so as to look perfect in the gowns created for her by Captain Molyneux – or ‘Molynukes’, as she called him.16 She had been a devotee of his since he opened his house in 1918; his designs made her look taller. It was Molyneux who dressed her when Joss first met her and he would continue to adapt fashion to suit her style for nearly forty years: she had ‘a rounded slenderness … tubular, flexible, like a section of a boa constrictor … [she] dressed in clothes that emphasised a serpentine slimness’. Joss, fashion aficionado, thought that the way she looked and dressed was wonderful.17

Twice married by the time Joss knew her, Idina was eight years older than him. She was the elder of two daughters born to the 8th Earl De La Warr (pronounced Delaware). Their brother, the heir, was Herbrand Edward Dundonald Brassey Sackville and, by the time Joss made his maiden speech in the Upper House, had become 9th Earl De La Warr, Under-secretary of State for the Colonies and Lord Privy Seal in the House of Lords.18 Idina was a legendary seductress. Joss, only nineteen years old, impressionable and driven by lust, had not resisted her wiles.19 He pursued her from 1920 although not exclusively.

Joss called virginity a ‘state of disgrace, rather than of grace’ and was not interested in seducing virgins. Lady Kilmarnock’s view was that young men should have affairs only with married women. Joss, whom she had so bewitched as a young boy with the mysteries of her toilette, seems to have paid a lot of attention to her on this issue as well, as Daphne Fielding can testify. Daphne’s memoir, Mercury Presides, contains a forgiving description of Joss’s flirtation with her (a virgin when Joss knew her): ‘It was inevitable that he should be conscious of such wonderful good looks as he possessed, and with these he had an arrogant manner and great sartorial elegance.’ When her father learned that Daphne had sat out on the back stairs with Joss during a dance, a furore ensued. After she told Joss about the row, he sent her an ‘enormous bunch of red roses’. She had been terrified that the sight of the flowers would incur her father’s wrath all over again, and had hidden them from him – ‘in my bedroom basin until they died – the first present of flowers that I had ever received’. Her fascination with Joss grew as her father’s disapproval intensified: Joss’s scornful way of looking at people, ‘an oblique, blue glance under half-closed lids’, was impudence personified.20 Joss, however, did not return her interest. He would without exception make a beeline for married women.21

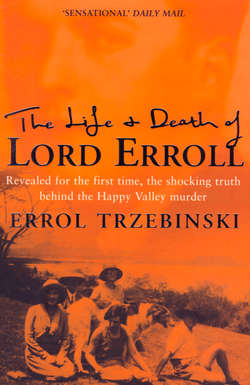

The easygoing lifestyle – in which people exercised sexual freedom without anyone suffering – that Joss now adopted would always be attractive to him. Idina, herself an advocate of promiscuity, found Joss irresistible – and one can see why in a picture taken of him as whipper-in to the American Army drag-hounds. As the best-looking in a bunch of four young bloods, he was as usual with the prettiest girl in the group. For his part, Joss relished the element of danger in his relationship with Idina. Her reputation was to him deliciously louche. Her first husband, Captain the Hon. Euan Wallace, MC, MP, had been in the Life Guards Reserve; she produced two sons by him, but after six years the marriage was dissolved. The two boys remained with their father and Idina virtually abandoned them. The society she kept in Paris was decidedly disreputable. Only her pedigree redeemed her. But her family life had not been happy; Idina was only nine years old when her parents separated, and, like Joss, she had grown up precociously and was easily bored. Even at school, classmates had been wary. She was smarter than them. One of her school contemporaries, coming across her years later in Kenya, admitted how terrified she had been of her. On this occasion Idina was as withering as ever: ‘Oh, yes,’ she murmured on meeting her old classmate, ‘I remember you – you never powdered.’22

Joss, madly in love with Idina, was longing to share his life with her. They made secret plans to marry and Joss played the eligible bachelor as Idina waited for her divorce from her second husband, Captain the Hon. Charles Gordon of Park Hill, Aberdeen. Charles had fallen for one of her younger unmarried friends and had wanted the divorce too. There was no uproar and terms were mutually agreed. In fact, Charles and Honor Gordon would be neighbours to Idina and Joss in Kenya. Charles Gordon had benefited from Kenya’s Soldier Settlement Scheme in 1919, and he found himself with 2,500 acres in the Wanjohi Valley above Gilgil. Idina received just over half the land as part of her divorce settlement.23

Joss, meanwhile, was ‘causing tremendous consternation in the hearts of the ripe young things’ in the marriage market-places. He was much in demand where débutantes flourished. He was scanned by dukes and dowagers, among bespoke kilts and bejewelled bosoms, upon which rested heirlooms.24 In 1922 he played the season – Ascot, Cowes, Henley, Cowdray Park and the Royal Caledonian Ball (the biggest of the London season) – having resigned his job at the Embassy in Berlin in March that year, nine months before the posting was due to end. His father must have been aghast at such fecklessness. But though his patience must have been wearing rather thin by this stage, he seems to have done his best to get his son back on to his career path. Perhaps Lady Kilmarnock put in some persuasive words for her favourite child, for in 1923 Joss became secretary at the Inter-Allied Rhineland High Commission.25 Nepotistic though the appointment may have been, he would undoubtedly have been able to make a useful contribution to the work of the High Commission. By now, he had acquired extensive experience in the Foreign Office and could switch to another language without a moment’s hesitation.

Adding to the tension in the British residence household at the time was the recent resale of Slains. Ellerman had arranged for the estate agents Frank Knight & Rubenstein, W. D. Rutley to auction it off.26 In the spring of 1922 Slains was sold for scrap – a considerable humiliation for the Erroll family.27

Idina was not long in following Joss out to Coblenz for a visit during the interlude between her decrees nisi and absolute. Joss wanted his parents to meet her, but he never let on to them his intention to marry her. He obviously realised that his parents were unlikely to share his enthusiasm for Idina, and even if he believed that she ‘could have walked off the bas-relief of dancing nymphs in the Louvre’ Lord and Lady Kilmarnock would take a lot of persuading.28 None the less, they would welcome her as his girlfriend.

Coblenz was a picturesque town at the mouth of the Mosel River, and had long been established as the trading hub for wine-growing countries and furniture factories. It was a sociable place: racing was popular, and since there was a good theatre, everyone went to the opera at least once, if not twice, a week.29

The British residence was surrounded by tall trees; in summer the building was entirely draped in Virginia creeper but during the winter its fish-scale tiled roof was exposed. It stood in the best spot of all among the French, Dutch, Belgian and American embassies, on the edge of the Rhinelagon, directly opposite the ‘bridge of boats’ which parted to allow barges through as they sailed up and down the river.30 Lord Kilmarnock’s position as High Commissioner entitled him to a guard and a sentry-box outside the gates of the residence; a Cameron Highlander did duty, marching up and down in a kilt. One of his more ceremonial roles was to pipe out distinguished guests down the drive as they left the house. Visits by dignitaries to the residence were photographed by the firm Lindstedt & Zimmermann, who specialised in turning photographs of the more important guests into postcards.31

Idina spent a lot of her time in Coblenz shopping for furniture for the new home in Africa that she would receive through her divorce settlement, choosing table linens and ‘ordering crêpe de chine sheets and exotic bathroom equipment’ including ‘a splendid green bath which in Kenya achieved a reputation all of its own ultimately, when it was believed to have been made from onyx’.32 Joss would accompany her, not letting on to his parents that he planned to share this future home of hers.

Joss’s general behaviour towards Idina and his family in Coblenz during Idina’s stay was observed by one of his contemporaries, Bettine Rundle from Australia, who had been sent to stay with her guardian’s daughter Marryat Dobie, one of Lord Kilmarnock’s aides. Bettine found herself at the British residence for eighteen months, party to the sensation created by Idina and to the interactions between Joss’s family and the staff attached to the residence. Thanks to Joss’s and Gilbert’s kindness, Bettine was included in the young people’s social life, attending the many parties and witnessing the childish pranks perpetrated by Joss and Idina. The staff were shocked at the spectacle of Idina with her Eton crop, and at how old she was. ‘Her figure resembled that of a boy, too; very, very slim’, her breasts flattened, ‘which seemed to make Joss complement her physically … They seemed like brother and sister; there was something alike in them.’33

These partners in crime masterminded a ‘little surprise’ to mark a visit from Monsieur Tirade, the French High Commissioner. While everyone else was bathing and changing for dinner they ‘sneaked downstairs and tied numerous pairs of knickers and brassieres from the top to the bottom of the banisters of the grand staircase into the hall below, where functions were always held. They had gone to the trouble of dying the underwear like the Tricolour, stringing the garments up like bunting in a totally inappropriate manner.’34 Lord and Lady Kilmarnock descended and – Voila! Joss’s father was acutely embarrassed before his guest of honour; Joss looked on in glee. Apparently his elders were always fearful of what he might do next. ‘He was generally regarded as something of a loose cannon,’ Bettine said. Today Joss’s and Idina’s prank might be regarded as harmless fun, but in the old school to which Lord Kilmarnock belonged one simply did not do that sort of thing.

Idina used lingerie for maximum arousal in the bedroom and taught Joss many tricks involving its removal. His favourite was to touch the strategic four points on a skirt undoing the suspenders underneath so deftly that the wearer would notice nothing until her stockings collapsed about her ankles.35 Underwear would continue to be a sensitive subject during Idina’s stay. She never fell short of taking ‘delight in Joss’s near-the-knuckle jokes’. ‘Covered in hay’ did the rounds in Coblenz.36

Such mockery of decorum outraged the Kilmarnocks. Joss’s father remarked that since Idina was so much older she should have known better.37 If Joss involved himself with such a woman, how could he expect to move expertly as a diplomat? Lord Kilmarnock feared for him and told him so, but his warnings fell on ears tuned only to amusement. If Joss had been smarting from the telling-off, his doting mother would soon have soothed his wounded vanity.

A portrait of Lady Kilmarnock painted that year shows a stunning woman. She exuded confidence and, like Idina, ‘was very stylish, usually surrounded by a good many subalterns from Cologne – and officers of the Guard … seeming not to want to grow old’. Joss ‘seemed to cultivate a peculiarly intimate relationship with Lady Kilmarnock’, and Bettine Rundle noticed that, even while Idina was staying, he continued to appear in his mother’s dressing room before dinner for a private chat. One evening, sauntering in, Joss had picked up the flannel dangling over the side of her wash-basin and gestured as if to wipe his face, when his mother snatched it away with a shriek, ‘That’s my douche cloth!’ ‘A lot of tittering between mother and son had gone on over his mother’s washcloth.’ According to Bettine, when Joss exercised his sense of humour he ‘always had to score a point – usually it had a smutty side’.38

Joss’s smuttiness could be hurtfully embarrassing. On his father’s staff was a stenographer, a Miss Sampson, with whom Joss had flirted. Sammy, as she was known, was dark, plain and middle-class but Joss made a point of never overlooking plain girls. Sammy had been invited to attend Gilbert’s birthday party, along with fifty others. She would be returning to London on leave the next day. A risqué innuendo in Joss’s impromptu speech during dinner had horrified everyone – ‘now that Gilbert had come … of age,’ he remarked at one point.39 His brother had never taken his jokes easily. Worse was to follow. Strolling across to Sammy, Joss wished her a good holiday; then, in falsetto, mimicking her Essex accent and loud enough to be overheard, he said, ‘Don’t forget to take your sanitary towels, will you?’ There was a hush. His father was very upset and there had been murmurs about the ‘Mrs Jordan coming out’. Sammy, having admired Joss, took a long time to get over the indignity. On the whole, though, his own generation tended to regard him as ‘killingly funny’.

Joss may have been in love with Idina but he was too bright not to realise that she would never be a model diplomat’s wife. She would earn a reputation as a superb hostess, she would never give a damn about what other people thought. ‘To Hell with husbands’ may have been her dictum, but they both lived by it.40 Even before his father had had his say, Joss must have known that the Foreign Office would never have kept him on as Idina’s husband. Divorced persons were not accepted at Ascot nor at court. Lord Kilmarnock had made it his business to discover all that he could about Idina and he gathered a considerable ballast against her. Both his parents remonstrated with him, cajoled him, reminded him of what his future could entail. ‘Lord Kilmarnock begged Joss not to marry Idina. Even making him promise.’ Joss had agreed, and Lord Kilmarnock was convinced that he would comply.41

However, unbeknown to the Kilmarnocks, arrangements for their register office wedding were put in hand for 22 September 1923. Idina, Alice de Janzé and Avie Menzies were in and out of London that spring and summer. If either of the ‘Sackville sisters’ was spotted, they made news: at the Chases or the Guards point-to-point, ‘over a line at Lordland’s Farm, Hawthorn Hill’.42 Joss joined Idina in England that summer and they simply enjoyed one another’s company, participating in the dance craze which was already in full swing. George Gershwin, currently billed as ‘the songwriter who composes dignified jazz’, arrived in London for the broadcast of ‘Rhapsody in Blue’ by Carroll Gibbons and the Savoy Orpheans. The Savoy was one of Joss’s favourite spots – the Orpheans and the Savoy Havana Band played simultaneously there on different floors; sometimes he and Idina would move off the dance floor to watch ‘speciality dancers’ in cabaret. They lapped up the city’s night life, going to Ciro’s to dine and dance after the theatre, to the Criterion, to the Café de Paris, to Oddenino’s and to the Piccadilly Hotel, where Jack Hylton’s band was also playing Gershwin in the ballroom. The Vincent Lopez Orchestra from the USA at the new Kit-Kat Club in the Haymarket was another hit, and since everything was within walking distance they could stay out all night, sometimes until dawn rose over the Thames. Avie was in London too, sharing Idina’s excitement while she had the chance.43

Idina’s engagement to Joss was announced in the Tatler on 19 September: ‘Lady Idina Gordon … is taking as her third husband, Mr Josslyn Hay, who will one day be the Earl of Erroll.’ The couple were on holiday at the Palazzo Barizizza on the Grand Canal in Venice when the announcement came out. Their hostess was Miss Olga Lynn, an opera singer manquée. Joss and Idina knew her as Oggie. She was not popular with everyone but had a loyal following, giving amusing and glamorous dinner parties for twenty at a time. Witty epigrams would be exchanged and ‘stunts’ performed for everybody’s entertainment. Oggie’s exotic set included Cecil Beaton, Tallulah Bankhead, Lady Diana Cooper, and Sir Oswald Mosley and his wife Cynthia – known in that circle as Tom and Cimmie. They would dine out at the Restaurant Cappello, much favoured by the Prince of Wales.44 Everyone knew one another. Whether swimming naked by moonlight in Venice, or attending Goodwood or Henley, their individual appearances and frolics were almost religiously recorded in the Tatler and the Sketch. This holiday in Venice cemented Joss’s friendship with Tom Mosley and ensured Joss and Idina a place in Oggie’s circle.

The Mosleys and Joss and Idina epitomised the postwar exuberance – they were highly optimistic about their own futures as well as the world’s, and they went about their lives on billows of hedonism. As Tom Mosley wrote, ‘We rushed towards life with arms outstretched to embrace the sunshine, and even the darkness … [we experienced the] ever varied enchantment of a glittering and wonderful world: a life rush to be consummated.’45 They were rich and they believed they could do anything. As far as they were concerned, war was over for ever.

In one photo, Joss and Idina parade on the Lido, Idina in a pleated white dress by Molyneux, as always, happy to show off her size-three feet by going barefoot. Hand in hand with his future wife, Joss follows the trend for ‘wonderful pyjamas in dazzling hues’.46 Tom Mosley, having been invalided out of the war, was forced to wear a surgical boot to redress an injury from an aeroplane crash. But his charisma more than compensated for his handicap, which was no impediment to attracting the likes of Idina and other beauties of the day with whom Joss had also dallied.

Mosley was the youngest Tory MP in 1919 but, within a year of meeting Joss, would leave the party in protest against the repressive regime in Ireland, switching allegiances to join Labour. Mosley would also give Neville Chamberlain ‘a terrible fright’ at Ladywood, Birmingham, contesting his seat and losing by only seventy-seven votes. Joss would emulate Tom’s style. They both fell for the same type of woman, and politically Joss’s ideas tallied with his at that time. They both believed that they could turn the world into a better place, providing they were given the power to act.

The Mosleys attended Joss’s and Idina’s wedding on 23 September. In their wedding picture, all arrogance is missing from Joss’s demeanour, replaced by a seldom seen expression of shyness or self-consciousness. Idina’s cloche hat is pulled firmly down. Wearing a brocade dust-coat trimmed with fur and her corsage of orchids, the bride looks, at best, motherly; she was thirty. Joss’s best man, the Hon. Philip Carey, and Idina’s brother Lord De La Warr were the witnesses. After the ceremony, Idina’s brother, Prince George of Russia, Tom and Cimmie Mosley and Lady Dufferin celebrated with them at the Savoy Grill.47 Joss’s family is conspicuous by its absence. The couple cannot have been inundated with wedding presents, given the circumstances, but Tom and Cimmie gave Idina ‘a crystal-and-gilt dressing table set, personally designed by Louis Cartier, and engraved with her initials and a coronet’.48

Lord Kilmarnock went berserk when he heard the news from London that Joss and Idina were married. According to Bettine Rundle, the rumpus had to be seen to be believed. For all Joss’s defiance of his parents’ wishes, he must have had a twinge of conscience because he returned to Coblenz with Idina to make his peace early in the New Year of 1924.49 Despite their rage and disappointment over Joss’s squandered abilities Lord and Lady Kilmarnock appear to have forgiven the couple for when their stay at the residence ended they were piped out by Lord Kilmarnock’s sentry, Captain Alistair Forbes Anderson. This was an honour they would not have received unless they were back in Lord Kilmarnock’s favour.50

Having ruined a promising career with the Foreign Office, possessing no money, and limited by the social restrictions that marriage to a divorcee imposed, Joss must have looked on Africa as an ideal escape. It was being said that he had ‘married … because he was very young and very headstrong and because Lady Idina had considerable income from De La Warr’. If this criticism was fair, Joss was following in the tradition of his ancestors. However, the Hays inspired jealousy in those who weren’t so witty or as attractive, and these allegations of marrying for money could have been thus inspired.51 Idina would always have her detractors; she was too successful with men not to attract criticism. Being well read and knowing absolutely ‘everybody’ – from Diana Cooper to Florence Desmond – she did summon a certain envy. And her legendary sexual appetite did not endear her to people. Even her future son-in-law Moncreiffe, not prone to exaggeration, pointed out, ‘My mother-in-law was a great lady, though highly sexed.’52

Some time after their visit to Coblenz to make peace with the Kilmarnocks, Joss and Idina Hay sailed off with all their chattels, ready for their first home together. Joss was embarking on his first voyage to the Dark Continent with the recklessness of a schoolboy gambler. Their fellow passengers would have consisted of government officials, business entrepreneurs, missionaries and big-game hunters. During the voyage attempts were made by most of those expecting to stay in Kenya to study a slim volume called Up Country Swahili. However, Idina and Joss were up to their usual pranks, courting scandal in a manner for which they were soon to become infamous. After a week or more cooped up on board Joss found himself shoved into a lavatory in one of the state rooms with the key turned on him by his female companion, ‘in order to escape an outraged husband’.53 Joss had narrowly missed being caught in the act of fellatio when the woman’s husband had arrived at their stateroom door wondering why on earth she was taking so long to dress for dinner. She apologised coolly and promised to join him after she had completed her toilette. Meanwhile, as the sun went down, Idina had been sipping ‘little ginnies’ in the ship’s cocktail bar. She recounted the incident with evident relish and amusement to someone who, on a visit to the British residence in Coblenz, relayed the anecdote to Bettine Rundle. According to Bettine’s informant, Idina had blamed herself for Joss’s behaviour; he had learned from her how to be such a rake.54

*In those days, applicants also had to prove they received a private income of at least £400 per annum.

*Menzies had served with distinction in the First World War. There was a widespread belief in the services that he was the illegitimate son of Edward VII. He was certainly closely connected with court circles through his mother, Lady Holford, who was lady-in-waiting to Queen Mary. He also had considerable influence in important government circles, and ‘as a ruthless intriguer’ used it shamelessly. In personal relationships Menzies was polite but never warm, ‘hard as granite under a smooth exterior’, as the wife of one of his Security Service colleagues observed. He drank heavily, loved hones and racing and was a club man (Philip Knightley, The Second Oldest Profession, p. 112). When he took over the SIS after Admiral Sinclair’s death in 1939 he was forty-nine. His successor, Sir Dick White, noticed that the file on Menzies was missing from the registry. The wartime chief had deliberately avoided any records ‘to preserve the fiction that he was the illegitimate son of Edward VII. “I paid ten shillings,” laughed White, “and got the name of his real father from Somerset House.”’ (Tom Bower, The Perfect English Spy: Sir Dick White and the Secret War 1935–90, p. 209).