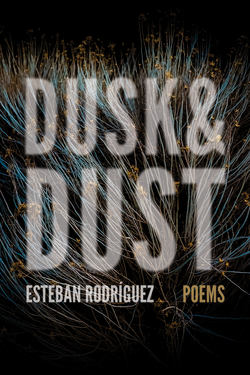

Читать книгу Dusk & Dust - Esteban Rodríguez - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFENCE

We weren’t exactly tourists anymore, amateurs at crossing over,

tossing change

and lint inside their half-cut, empty jugs of milk, nodding as they

blessed us

from behind the fence; their scabbed fingers anchored to the plastic’s

jagged edge,

heavy with the weight of pity, stares. We weren’t exactly shocked by all

the begging

at the border, the women sprawled outside the bridge, sleeping children

cradled

in serapes, strapped like hammocks below their mother’s breasts,

as hordes of flies

dove at their eyelids and crawled across their swollen cheeks. As sad

as the scene

was supposed to be, I still had fun feeding quarters down the slot,

swinging past

the metal arms, the rattle from the turnstile louder than pennies dancing

inside a can.

We’d matured from trivialities, group photos at the flagpole,

at the emblem

of an eagle with a snake perched above a cactus, copper cruelly

chipping off,

a metaphor for the landscape of this country. At ten, I had no

metaphors

for barefooted boys selling Chiclets like insurance, running after

every passerby,

tugging their sleeves, nagging how their gum was cheaper than

the other guys’.

But diez centavos was too desperate to translate to my mother’s ears,

and even though

she spoke their language, she used her English silence to mute

their pleas; those shouts

for discount pharmaceuticals, healing herbs and Freon, strings of garlic

and streetside

taco stands drenched in spices I had never smelled. We were them

without the burden

of being them, shared last names with them, an economic convenience

living so close

to them, but when my mother tugged me closer to her waist, clenched

the collar

of my white and sweaty shirt, I heard the tension in her grip saying

I was not,

would never be one of them, would play the role of ‘in-between’ instead,

the relative

from el otro lado, the boy straddled on the valley of two geographies,

walking over

with his stoic, middle-aged mother, unaware that her stay-at-home salary

didn’t come

with dental, that her enamel was dissolving, riddled with cavities across

her molars,

where she’d thrust and dig with toothpicks, nails, scoop out the half-

chewed gunk

of food, repeat the rhythm after every meal. And there came a point

when all she scraped

was nerve and gum, when her habit spread into years of sleeplessness,

aggravated

by a dentist speaking Spanish too clinical to understand: drilling, talking,

drilling,

pausing, yanking out the reasons why we made our trips, those weekend

afternoons

crossing back high on anesthesia and lobby candy, staggering past

the line of women

still staring through the heavy mesh, and still melting along the shadeless

pavement,

wondering, I imagined, how our sloppy smiles tasted.