Читать книгу The Diary of a Rapist - Evan S. Connell - Страница 6

ОглавлениеTwo confessions: 1. A handsome first edition of this book sat on my bookshelf for years before I could bring myself to read it—the book arrived and I put it away, unopened, peculiarly disconcerted by what I feared I might find inside. 2. The current copy that I carry with me as I write this is a used paperback reissue from several years ago. It arrived with a paper EX LIBRIS bookplate decorated with three butterflies (a little too Nabokovian) and the mark of its previous owner, Courtney Biggs, in green ink. There is no sign of Courtney ever having cracked the spine. Did just the idea of The Diary of a Rapist—the title alone—put her off; was there something terrifying in the notion that a rapist might keep a diary, might now make us privy to his pervy thoughts? That was part of the problem for me—the fear of being overwhelmed at either extreme, icked out or seduced. What is the power of this book—how does it work on us? Does the writer, Evan S. Connell, know too much? And what exactly is that—too much? Something deep and dark about us as humans, something about American society, something about the twists our need for affection, validation, and power can take? Connell offers the reader a challenge, a chance to locate oneself in the notions his character posits—“...when that moment comes—that one instant when we’ve got the power either to love or hate, with nothing in between, how often do we hesitate?”

On the surface what is unsettling about this book is how different it is from the author’s best-known books. Connell is a writer’s writer, author of eighteen books—the most well known of which, the Bridge novels and Son of the Morning Star, are remarkable for precise rendering of the delicate hues of the ordinary, the everyday, capturing subtle if sometimes strained exchanges, intercourse—in the way that our English teachers meant for the word to be used. He has delivered us the upper-middle-class Kansas City of his youth in the two Bridge novels, a historic and insightful rendering of General Custer in Son of the Morning Star, he has charmed us with his craftsmanship and artistry in his volumes of poems, short stories, and most recently a book on the life of eighteenth-century painter Francisco Goya.

Throughout there is a glassy calm, a discrete breath-holding quietude that one hardly suspects could flip itself into the sharp, unapologetic, confrontational Diary of a Rapist. The Diary of a Rapist is about rage; rage lurking just beneath the surface, bubbling up, seeping out, staining us, poking at us, reminding us of what has happened, what might happen, what will happen if we don’t watch out.

One reason this book might not be so well known is because it is uncharacteristic of the artist’s oeuvre. Then again, one of the things that has kept Connell less known than he should be is that his oeuvre isn’t easily described: his territory shifts with each volume, absenting him from categorization. Eccentric, idiosyncratic, he writes what he wants. Throughout his body of work there is a consistent clarity, an unblinking authorial eye that doesn’t render judgment but simply presents his characters real and imagined, writ large and small, leaving room for the reader to participate in the creation of the narrative.

And while one likes to think of readers as smart souls who read not just to be entertained but to travel the mind’s eye, one is ever aware that we’ve devolved into a society that rushes to be entertained, made to feel happier, lighter, thinner, less depressed.

The Diary of a Rapist is the dark and unpleasant story of Earl Summerfield, a civil servant in his twenties working as an interview officer in the State Unemployment Bureau, and his wife Bianca, a schoolteacher seven years his senior. It is a portrait of a man unraveling; like a spool of string being taken for a run by a kite, Earl is taken for a run by his fantasy life, slipping out of control as the string pulls in one inevitable direction. Early on Earl confesses, knowing the truth—his fear—that he is what he accuses others of being: boring. Summerfield is numbed by the narcotizing effect of routine, the petty politics of office life. “Wiggle my toes for amusement. Look down at my shoes to see if the leather’s got any new cracks.” His diary charts the minutiae of his existence; how he sleeps, what he eats, the weather, the passage of time, etc. With the same obsessive, cruel detail that he observes—and judges—everyone around him, Earl is on himself—at one moment filled with a nauseating self-loathing and the next applauding the superiority of his intellect. These emotional shifts become a series of stress fractures, allowing or forcing Earl to move away from reality and further into a fantasy life. But what is real and what is imagined? Hold that thought and play it against Earl’s increasing consumption of newspaper accounts of crimes—stories of men and women robbed, stabbed, beaten to death, throats slit, cut to pieces.

These seemingly random attacks horrify him, make him wonder what kind of world we’re living in—he is “beginning to think we’ve gotten to be the most savage nation on earth. Not so peaceful and charitable and decent as we claim.” And as surprised and horrified as he is, there’s something more; Earl is eerily close to the impulses and information reported, like an arsonist returning to the scene. And though these crimes are not Earl’s doing, does reading about them not only infuriate him but on some level prompt him to believe there is a place in this world for such activity?

As his obsession with crimes builds, so too does his interest in punishment, leading him to chart several criminals’ progress towards the death chamber. He also makes multiple references to Church and God, calling into question the power the Church holds over those who believe. And then there is Earl’s terribly troubled relationship to women and to his own sense of masculinity. He writes about Bianca plucking a hair from her chin, and wonders why she plucks it when she so clearly wants to be a man, and is more of a man than he. On Valentine’s Day he treats himself to a bath—wondering if he is more of a woman than his wife, liking this seemingly feminine indulgence. He writes of wearing Bianca’s clothes: “. . . laced myself into one of Bianca’s girdles, then put on stockings, hat with veil, and paraded before the mirror. . . .” Earl is filled with thoughts of revenge, violation, getting back at women for what they have done to him. “I could tie her to the bed. Then carve away! Yes, see how she likes it. Or shove in a broomstick—a bird on a spit! That would serve her right for what she’s done to me.”

On Washington’s birthday he spots the beauty queen, “The Whore of Babylon.” “Then that bitch in the bathing suit climbed up on the stage wearing a cardboard crown & carrying a scepter, went parading back and forth to show off her tits. No shame. No modesty. . . . She looked to me like one of those professional sluts from Hollywood. If she isn’t the symbol of American rottenness, what is?”

The madness is building; on March 18th, he strikes Bianca. “Tonight all of a sudden I stood up at the table and without a single word of explanation slapped B across the mouth. She’d been talking while I was trying to think, that’s why she was punished. However I was only the instrument—decision to punish her wasn’t made by me because I don’t recall drawing back my arm—it moved by itself exactly as though pulled by a string. I was helpless to prevent it, could only watch.”

On July 4th, Independence Day, the day he presumably rapes the beauty queen, his diary is silent. He reappears, waiting to be caught, and goes on to say that “the Devil is supposed to have a forked penis so he can commit sodomy and fornication simultaneously, yet we build gods in the image of ourselves because it’s implausible to do otherwise, consequently there’s no reason for me to feel upset. How can one already worn out by this corrupt world understand Incorruption?”

In a recent interview with Greg Bottoms in Bookforum, Connell talked about Diary:

It started when I read in the newspaper about a beauty queen who had been raped on two different occasions by the same man. Both rapes occurred under almost identical circumstances, but after the second time he drove her home. He wanted to make sure she got home safely. And he thought—I am convinced—that if she truly understood him, when she realized that he was a nice man, they could become properly acquainted, have lunch together, visit the zoo together, get married, and live happily ever after. I suspect that only in America could anyone be so deluded. Only in America, addled by the Puritan legacy.

Only in America. I maintain a view of post-World War II American fiction in which one sees the distinct and prickly seeds of entitlement, greed, frustration, disappointment, the fear of failure, rage at the need to keep up all blooming in direct response to a period of prosperity, social and economic expansion, and the spread of American Dream and Great Society ideology.

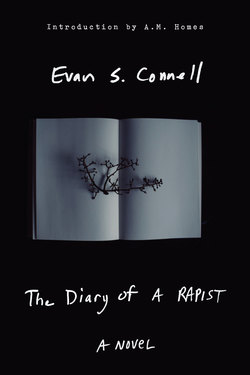

The Diary of a Rapist, originally published in 1966, is a deeply American novel, located somewhere between Nabokov’s Lolita and Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho. Like Lolita and Psycho it relies on the narrator’s entries, his registration of himself as witness to his own life—as if to say to the reader, please don’t forget me, lest I forget myself. And in all three one wonders about the split between reality and fantasy, how much is actually happening—in deed and/or in thought.

There is a flatness to Earl Summerfield, an absenting or disassociation of self, which perhaps allows his violent behavior to cross the barrier from thought into reality. In these splintered diary fragments Connell builds a convincing portrait that holds up well over time. It is as modern and terrifying a novel now as it was in 1966.

We have continued to consume this foul reporting, this “news”—if you can call it that—as a kind of perverse/erotic fish food addictively sprinkled onto our breakfast cereals; we eat it staring, numb, at the superbright colors of the flat-screen television, cruising through the hundreds of channels, nonstop twenty-four-hour news, real cop shows, fake cop shows. . . . We have by now so confused reality and fantasy, our sense of the moral and the criminal, that we are often hard-pressed to tell the difference. The questions raised by Connell have become all the more prescient. What in fact are we consuming—are we eating ourselves alive?

—A. M. HOMES