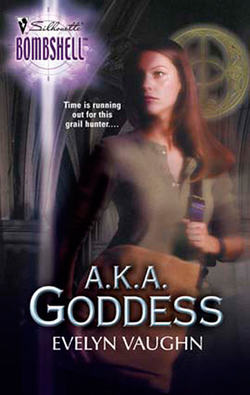

Читать книгу A.k.a. Goddess - Evelyn Vaughn, Linda Winstead Jones - Страница 15

Chapter 6

ОглавлениеI was expecting Lex to call—heck, I’d half expected it the day before. This was probably his version of giving me space.

I just hadn’t planned to be marinating in the destruction that powerful men so often wreak when he did.

After we checked out of the Holiday Inn, I rented a little silver Renault Clio. The train didn’t stop at the small town of Lusignan, where Rhys and I were now walking. What had once been a center of power was now a rural town. And the glorious castle—one of many—which the fairy Melusine had supposedly built for her bridegroom in one night…

Long gone. Nothing left but a sunny, public walking path where once the castle had stood, and trees, and an uninterrupted view down to the River Vonne. The castle had been razed for harboring Huguenots, adding to my frustration about finding anything. Whatever the goddess worshippers might have hidden at Château Lusignan was history, thanks to devastation and religious intolerance. Thanks to dark power.

My phone trilled out “Ride of the Valkyries” at the exact wrong time. When I glanced at the caller ID and saw it was Lex, I rolled the call over to voice mail.

Trust me, Lex. You do not want to talk to me right now.

Rhys glanced at me and my phone, then said, “Any goddess cult that worshipped Melusine would have gone underground by the thirteenth century—fourteenth, at the latest. Would they not?”

I fingered a little purple flower beside the path. “Mmmhmm.”

“And Lusignan was torn down, stone by stone, in 1574?”

Over religion. “A tower was torn down later.”

“So what did you expect to find?” asked Rhys.

“Not the chalice,” I admitted, though it would feel right to uncover it here at Melusine Central. “Just…a clue. Something. We have to start somewhere, don’t we?”

He looked around us and murmured, “Three fair figures…”

That was the first line of the nursery rhyme that my family has passed down for generations, seeming nonsense with a hidden meaning—like “Ring around the Rosie” being about the bubonic plague, or “Mary Quite Contrary” being the Queen of Scots. Nursery rhymes rarely attracted the attention of people in power, so they made a great treasure map.

Ours started, “Three fair figures, side by side…” As a child, I’d pictured people; kids are that literal. As a scholar, I knew the “figures” could be anything, standing stones or towers or trees or buildings.

Nothing stood in threes at Lusignan. Not that we could see.

My phone rang again. Lex. This time I just turned it off. My inner good-girl protested that it could be important, it could be an emergency, how could I be so selfish….

AKA the Eve Syndrome, holding ourselves responsible for everything. Ten years ago, before I had a cell phone, I couldn’t have stressed about it. I chose not to this time, either.

Instead, I raised my face to the blue sky, breathing in the fresh air. “This isn’t where we need to be looking.”

“I was afraid you’d say that.” Rhys spread his arms to indicate the commons around us. “So where do we go next?”

“To the women,” I decided, looking down the hill toward the two-lane road—and a Romanesque church that had survived the castle’s destruction. “And since I’m not ready to go door-to-door asking questions, I suggest we try St. Hilaire down there.”

Why did I sense that Rhys didn’t like my suggestion? He didn’t frown. He just said, after a moment, “Do you want to borrow my handkerchief?”

For my head. This was Europe.

“Thanks,” I said, accepting the neatly folded cloth.

“I’ll get the car and meet you outside.”

Once upon a time, the women of Lusignan would have gathered around the town well to wash clothes or collect water, and to bond. Wells are famous for their goddess connections.

If you’ve ever tossed a penny into a fountain and made a wish, some part of your soul must have understood their magic.

With the advent of modern plumbing, we’ve lost that. Now, elderly Catholic women tend to congregate at church.

The twelfth-century St. Hilaire de Lusignan had thick walls, round arches, and heavy piers instead of mere pillars. Its graying stone and blue-slate roof hinted at what the castle may have looked like—beautiful. When I pushed through one of its heavy double doors, I stepped into the scent of centuries of incense and wax and wood polish, of Yuletide greenery and Easter flowers, of continued faith. And it felt…

It felt powerful in a way few places can.

You don’t have to be Catholic, much less a practicing one, to appreciate the holiness of such a place.

As my eyes adjusted to the shadows, I respectfully draped the handkerchief over my hair. In random pews, pretending not to notice my invasion of their territory, knelt three old women.

Yes.

On instinct, I strode to the front pew, genuflected, then sidestepped in and sat near the woman I assumed was most important who, kneeling, was saying her rosary. She had woven a crown out of her white braids. She wore a black shawl over that, and a black dress, and a thin wedding band.

She seemed somehow timeless. That made sense. Old women, wise women, are the most powerful brand females come in.

If I’d had a rosary, this would be easier. Instead, I unclasped the chain that held my chalice-well pendant and laid it on the wooden pew between us, in a loop.

When the woman beside me said “Amen” and slanted her gaze toward the chain, I murmured, “Un cercle et un cercle.”

Her sunken eyes searched my face suspiciously, slid with disapproval to my camisole, then dropped to the necklace. Then, as I’d hoped, she looped her rosary across it. “Pour toujours.”

Basically, “Circle to circle, never an end.”

I’d made contact.

“I apologize for interrupting your prayers,” I whispered, still in French, but she shook her head.

“St. Hilaire hears from me each day. He will not mind some peace. You have come for the fairy, oui?”

“I’m here for her cup.”

She snorted.

“Is it not time for the cup to be found?” I asked gently.

“Perhaps…perhaps. But few daughters are worthy to find it. Few understand its power.”

“Then help me to understand.”

Her chin came up as she looked me over again; cargo pants, spaghetti straps. I’d left the backpack with Rhys. “You are too young and too beautiful. You will not want to understand.”

Not want to? “But I do. Please!”

She picked up her rosary, dismissing me. So I added, as quickly as I could, “‘Three fair figures, side by side.’”

I said it in English, but the old woman must have understood, because she lowered the beads to her lap. She crossed herself for Saint Hilaire, turned back to me and said in English with a heavy French accent, “Go on.”

I recited:

“Three fair figures, side by side,

Mother, son and brother’s bride.

In the hole where hid her queen,

Waits the cup of Melusine.”

The old woman nodded slowly, intrigued. “Perhaps you are one of us, at that.”

“But that doesn’t tell me where the figures are, what they are. It doesn’t say if the hole is a pit or a cave or a well.”

“Non!” My companion reverted to French. She seemed to like French better, and she was old enough to demand what she liked. “It tells more, if you only listen correctly.”

“I want to.” I touched her hand in supplication. “Please…”

She sharply nodded her decision. “You must drink of it.”

I blinked. “Excuse me?”

“You must promise that, should Melusine’s daughters help you in this, you will not forsake her. Should you find her chalice, you must drink her essence. Or you must let her sleep.”

“But…” My intellectual, academic side was having major trouble with this. I was supposed to drink out of an ancient cup? Couldn’t that screw with carbon dating or DNA? And how did I know what the cup had last held? The likelihood of something gross like poison or blood sacrifices was low, but still!

Still… “I will.”

“Then you will regret it.”

Was she trying to piss me off? “I promise to do as you ask, if you help me find the cup.”

The woman beside me turned—in several ungainly lurches, her body no longer as lithe as it surely once had been—to look behind her. I followed her gaze and saw that the other two old women had been unapologetically eavesdropping. The three were somehow one, I realized, logical or not. They went together like the Norns or the Fates or the Wyrd Sisters.

They nodded in answer to my companion’s silent question.

She turned back to me and said, very intensely:

“Quatre nobles avec le même coeur

Mère, père, fils, et belle soeur

Dans le tròu se cache sa reine

Attend la tasse de Melusine.”

Then she nodded, satisfied.

I wasn’t satisfied. From one cryptic nursery rhyme to its cryptic translation? Still, it seemed significant to her, and I was already noticing minor variations from my family’s version.

I slowly repeated the rhyme, word for Gallic word.

My impromptu teacher—or priestess, even?—squeezed my hand. “Perhaps you are the one. But you must remember—”

Which is when the doors at the back of the church opened, and Rhys entered. The women took one look at him and turned back to the altar, back to their devotions, as if the priest himself had walked in on us.

Rhys noticed me, opened his mouth, then awkwardly closed it. Then he pointed at himself, made walking-fingers, and pointed outside.

Then he escaped. But the damage had been done. My companion had reverted to praying.

I waited a few minutes, assuming she would finish. She just kept repeating the prayers, so finally I interrupted her. “You were about to say something. What is it I must remember?”

For a long moment I feared she’d reconsidered. Then she pressed my chalice-well pendant back into my hand and patted it, for all the world as if she were my own grandmother.

“Remember that Melusine survived,” she said.

When I emerged into the sunshine, Rhys stood across the road from the church, leaning against our Renault. He ducked his head while I looked both ways and jogged across to meet him. He winced up at me when I reached his side.

“I am sorry,” he said, before I could speak. Not that I’d meant to. I felt strangely light-headed, like after a deep meditation, or a movie…or a nap. A nap with powerful dreams.

Still, I couldn’t ignore him. “Sorry for what?”

“You had the whole nave, but as soon as they saw me…” He mimed turning a lock against his lips, then tossed the imaginary key over his shoulders, down the hill.

I grinned at the gesture, but I felt for him, too. Rhys seemed like a good guy, but just because he was a man, he came across as some kind of threat. Reverse discrimination, even unintentional, is still discrimination. “Don’t worry about it.”

Even though it felt weird, just how much authority they’d seemed to grant him. As if they sensed something I didn’t.

Rhys simply grinned and said, “Maggi? You have a handkerchief on your head.”

I palmed it off and gave it back, and he was so not an authority figure.

Which isn’t to say he didn’t have his own personal power.

“So where to?” He opened the car door and popped the locks. “Have you solved the mystery of the Melusine Chalice?”

“Nope. We’re still stuck with the obvious possibilities.”

“Those being…?”

I went around the car and climbed into the passenger seat. If we were doing Melusine’s home tour, I knew exactly what came next. “Did you by any chance pack swim trunks?”

Deeper and deeper I swam, kicking my feet for power, stretching my hands ahead of me into the murky river. I squinted at water plants, at little clouds of billowing silt, at a turtle paddling past.

I thought I saw something—a stone? Perhaps it was the large remains of a relic or a ruin, some unlikely but not impossible hint that Melusine Was Here. Tightness built in my chest from lack of air, but I was so close. A few more silent kicks…

Now I could see it was an old barrel. Rusty and moss covered. Years, not centuries, old.

Blowing the last of the air from my nose in bubbles of disgust, I aimed for the surface. I broke into the dappled summer sunshine with a splash and a needy gasp.

Rhys, on the wooded bank, called, “Do you see anything?”

“Not yet.” I was still treading water, kicking my bare feet, enjoying the gentle pull of the Vonne’s current against me. I still couldn’t believe I’d left my suit home. Me! “I’m going down one more time before we give up on this spot.”

He nodded. Rhys did have a pair of swim trunks. Since he claimed that his swimming amounted to little more than a dog paddle, I wore them with my camisole while he kept watch from the bank. Neither of us actually said this was better than me swimming in my underwear, but it so was.

I took a deep breath and dove again. Deeper and deeper. Freer and freer. Free of gravity, free of whatever kernel of attraction was flirting its way between Rhys and me, free of anything but one simple goal.

Try to find, against all reason, the remains of Melusine’s “fountain” in the Colombière Forest.

It wouldn’t be the first time goddesses were worshipped at a spring—like in Bath, or Lourdes, or the Chalice Well in Glastonbury.

Deeper. Freer. Was that possibly a bowl of some sort, on its side on the bottom?

Tightening my throat against the need to breathe, I kicked closer—and startled away another turtle, in a burst of panicked mud.

I reluctantly gave up the peace of submersion for the surface, yet again. Luckily, the surface was a nice place too, with birdsong and wildflowers and gently stirring tree branches…and a far-too-intriguing companion for my peace of mind.

“Nothing,” I called, when he waved to show he’d seen me emerge. Then I began a strong sidestroke back to shore. “If there was a sacred spring along here, it will take people with more experience than me to find the signs.”

It wasn’t like we’d seen either “three fair figures” or the French version, “four nobles.” If they’d been sentinel trees, the likelihood of them living this long was low. If they’d been standing stones, we hadn’t found them.

I waded out, my hair streaming water down my back, my toes gooshing deliciously in the mud. Rhys offered a warm hand, and I accepted it, and he pulled me firmly onto the grassy bank.

Close to him.

I noticed his gaze sink to my breasts, under a film of wet camisole. My breath fell shallow…but in a good way.

He noticed me noticing, let go and turned away.

“I’m sorry,” he called over his shoulder, clearly discomfited. “I’ll walk ahead, see if there are any more promising spots.”

Oddly disappointed, I used yesterday’s T-shirt to dry off my feet before I put on my socks and boots to follow him. Interesting fashion statement, hiking boots with swim trunks. Very unacademic. I liked it.

I rezipped my backpack, which I’d apparently left open, and shouldered it. Then I hiked happily after Rhys, through what legend had it were enchanted woods.

When he glanced a truly self-conscious welcome over his shoulder and kept walking, I had to know. “Are you married?”

He stopped, startled. “What? I am not. Why?”

Because you act like it’s a sin to notice a woman’s body. It wasn’t as if he’d ogled me. “Just curious,” I said.

Rhys stared at me for a long moment. “I was engaged once,” he confessed. “She died last year, before we could marry.”

“Oh.” Way to feel guilty, Mag! “I’m so sorry.”

He shrugged one shoulder and started walking again.

“So, Aunt Bridge has been researching the goddess-worship side of Melusine,” I said, to change the subject. “I’m more into the mythology. You’re her assistant, give me an overview. How would it work? Women worshipping a goddess, I mean.”

For a moment he seemed lost in other thoughts. Then he said, “That depends on the time period. Gaul stayed pagan well into the Dark Ages. Probably they would meet in a sacred grove.”

Considering that we were in a forest, that hardly narrowed things down. “How would the scene have changed once Europe converted to Christianity?”

“By the sixth century, ritual groves were being destroyed in an attempt to convert blasphemers. Like Charlemagne cutting down the sacred oaks of the Saxons.”

“And that worked? If you cut down my sacred trees, you’d tick me off worse than before.”

He’d slowed his step, so I no longer felt like I was chasing him. “Back then, power defined your ability to lead. If your gods were so great, how could they let us cut down their trees?”

I glanced at the trees around us, dappled greens and golds and browns, and felt sorry for them. “You’re not really saying that your god can beat up the other boys’ gods?”

He grinned. “The remaining pagans would have met in secrecy—at night, or in the woods.”

“So if these people worshipped a goddess who was connected to a local spring…”

Thankfully, he picked up the thread of my idea. “Then they would have met near that spring. Their ceremonies would resemble witches’ circles, complete with moonlight and cauldrons.”

“Or cups. Or bowls. Or chalices.” Or grails.

“That is it exactly,” he agreed.

I took a moment to look around us. The banks of the Vonne were slightly rockier. It was all fairly soft limestone. One boulder looked particularly significant somehow, especially white amidst vines and brush.

“How far have we come since Lusignan?” I asked.

“I’d imagine we’ve come four or five kilometers. Why?”

I was noticing another bank of white limestone, near the boulder. “Do you suppose the Melusine worshippers would have come this far out?”

“If they feared the Church more than they feared wolves.”

I noticed a third length of limestone. My pulse picked up.

Three fair figures?

I sank down into an easy crouch to untie my boots.

I kicked off one boot, then the other and put down my backpack.

Then, I waded in to swim the water where Melusine the goddess may have once bathed.