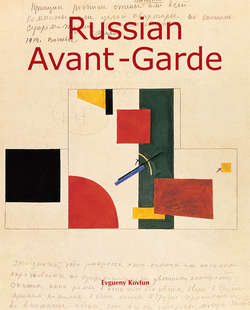

Читать книгу Russian Avant-Garde - Evgueny Kovtun - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

I. Art in the First Years of the Revolution

The Spiritual Universe

ОглавлениеFor most painters, despite the discoveries of Galileo, Copernicus and Giordano Bruno, the Universe remained geocentric (from an emotional and practical point of view, that is to say, in their creativity). The imagination and structures in their paintings remain pledged to a terrestrial attraction. Perspective and horizon, notions of top and bottom were for them undeniably obvious. Suprematism would disrupt all of this. In some way, Malevich was looking at Earth from space or, in another way, his ‘spiritual universe’ suggested to him this cosmic vision. Numerous Russian philosophers, poets and painters at the beginning of the century returned to the Gnostic idea of primitive Christianity, which saw a typological identity between the spiritual world of man and the Universe. ‘The human skull,’ wrote Malevich, ‘offers to the movement representations of the same infinity, it equals the Universe, because all that man sees in the Universe is there.’[10] Man had begun to feel that he was not only the son of Earth but also an integral part of the Universe. The spiritual movement of man’s inner world generates subjective forms of space and time. The contact of these forms with reality transforms this reality in the work of an artist into art, therefore a material object whose essence is, in fact, spiritual. In this way the comprehension of the spiritual world as a microscopic universe brings about a new ‘cosmic’ understanding of the world. In the 20th century this new comprehension lead to the creation of radical changes in art. In the non-objective paintings of Malevich, whose rejection of terrestrial ‘criteria of orientation,’ notions of top and bottom, right and left, no longer exist, because all orientations are independent, like the Universe. This implies such a level of ‘autonomy’ in the organisation and structure of the work that the links between the orientations, dictated by gravity, are broken. An independent world appears, an enclosed world, possessing its own ‘field’ of attraction-gravitation, a ‘small planet’ with its own place in the harmony of the universe. The non-representative canvases of Malevich did not break with the natural principle. Moreover, the painter goes on to qualify it himself as a ‘new pictorial realism.’[11] But its ‘natural character’ expresses itself at another level, both cosmic and planetary. The great merit of non-objective art was not only to give painters a new vision of the world but also to lay bare to them the first elements of the pictorial form, while going on to enrich the language of painting. Shklovsky expressed this well in talking about Malevich and his champions: ‘The Suprematists have done in art what a chemist does in medicine. They have cleared away the active part of the media.[12]’

At the beginning of 1917 Russian art offered a true range of contradictory movements and artistic trends. There were the declining Itinerants, the World of Art, which had lost its guiding role, while the Jack of Diamonds group (also known as the Knave of Diamonds), was quickly beginning to establish itself in the wake of Cezannism, Suprematism, Constructivism and Analytical Art. To characterise the post-revolutionary Avant-Garde, we will only address the essential phenomena of art and the principle events in the world of painting, focusing less on the work of painters than on the processes taking place in art at that time and on the issues raised by the great masters, who represent art’s summit at the time.

Ivan Puni, Still Life with Letters. The Spectrum of the Refugees, 1919.

Oil on canvas, 124 × 127 cm.

Private collection.

Olga Rozanova, Non-Objective Composition (Suprematism), 1916.

Oil on canvas, 102 × 94 cm.

Museum of Visual Arts, Yekaterinburg.

Soon after the October Revolution, a group of young painters gathered at the Institute of Artistic Culture (IZO), the People’s Commissariat for Enlightenment (Narkompros), directed by Anatoly Lunatcharsky. For them the Revolution signified the total and complete renewal of all life’s establishments, a liberation from all that was antiquated, outdated and unjust. Art, they thought, must play an essential role in this process of purification. ‘The thunder of the October canons helped us become innovative,’ wrote Malevich during these days. ‘We have come to clean the personality from academic accessories, to cauterise in the brain the mildew of the past and to re-establish time, space, cadence, rhythm and movement, the foundations of today.’[13]

The young painters wanted to democratise art, make it unfold in the squares and streets, making it an efficient force in the revolutionary transformation of life. ‘Let paintings (colours) glow like sparklers in the squares and the streets, from house to house, praising, ennobling the eyes (the taste) of the passer-by.’[14] wrote Vladimir Mayakovsky, Vassily Kamensky and David Burliuk. The first attempts to ‘take art out’ into the streets were made in Moscow. On 15 March 1918, three paintings by David Burliuk were hung from the windows of a building situated at the corner of Kuznetsky Most street and the Neglinnaya alleyway. Interpreted as a new act of mischief by the Futurists, one could already see the near future in this action. In 1918, Suprematism left the artists’ studios and for the first time was brought into the streets and squares of Petrograd, translated in an original way in the decorative paintings of Ivan Puni, Xenia Bogouslavskaia, Vladimir Lebedev, Vladimir Kozlinsky, Nathan Altman and Pavel Mansurov. The panel painted by Kolinsky, destined for the Liteyny Bridge, was characterised by simple and lapidary forms, an image rich in meaning, without unintentional or secondary lines. The artist knew how to construct an image with few but pronounced mixes of colours: the deep blue of the Neva River, the dark silhouettes of war ships, the red flags of the demonstration that march along the quay. The watercolours of Kolinsky are not only decorative and joyful, but also characterised by an authentic monumentality. With a minimum use of forms and colours, the work acquires a maximum emotional charge.

The sketches of Puni, Lebedev and Bogouslavskaia reflect strong Suprematist influences. In these initial experiences, however, the painters conceived the principles of Suprematism in a somewhat ‘simplistic’ way, seeing it from a decorative and colour point of view only as a new procedure in plane organisation. They did not grasp the intimate sense of this movement and its philosophical roots.

Mikhail Matiushin, Movements in Space, 1922.

Oil on canvas, 124 × 168 cm.

The State Russian Museum, St Petersburg.

10

K. Malevich, God Is Not Cast Down. Art, Church, Factory, Vitebsk, 1922, p.7.

11

Sub-heading of Malevich’s brochure ‘From Cubism to Suprematism’, published in 1915.

12

V. Shklovsky, ‘Space in Art and the Suprematists’, Jizn Iskousstva, 1919, No. 196–197.

13

Izobrazitelnoie Iskusstvo, 1919, No. 1, p.28.

14

A. Mayakovsky, Collection, Leningrad, 1940, p.90.