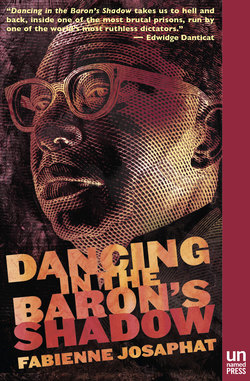

Читать книгу Dancing in the Baron's Shadow - Fabienne Josaphat - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTWO

Nicolas L’Eveillé stood between his friends Georges Phenicié and Jean Faustin. They were peering over a stack of typewritten pages Nicolas had just freed from the confines of a rubber band.

He could smell the cigarettes and coffee on his friends’ breath and could feel the tension as the setting sun threw shadows across the walls of his study. Next to the manuscript was a small black notebook stuffed with newspaper clippings, Nicolas’s black Smith-Corona, and a photograph of his wife, Eve, her black hair perfectly curled, holding their newborn.

Jean Faustin, whom Nicolas and his close friends affectionately called Jean-Jean, gingerly slid a newspaper clipping from the notebook. He held it away from the window. In the newsprint photograph, a man disfigured by a scar from his eye down to his chin grinned in the sunlight. Standing next to the man on a balcony was Papa Doc, his smirk and glasses unmistakable. Jean-Jean’s age-spotted, bald head tilted back as he let out his habitual, pensive grunt. He was in his seventies and had lived through enough to move away from the window lest anyone see what they’d found. He retreated to an empty space between the bookshelves that lined the walls.

“I don’t understand,” Georges said. His large belly rolled forward as he leaned over to extinguish his cigarette in an empty espresso cup. He was a handsome, heavyset man who always wore white or beige linen clothing that set off his inky skin. He had large eyes and purple gums that flashed nebulous teeth when he spoke. His rich baritone filled the room.

“I know you said you wanted to write a book, but—when did you have the time to do all this?”

“Took me a few months,” Nicolas said. “But never mind that. I called you here because I need your help.”

Georges’s fearful eyes belied his calm voice. “Help?”

“As you know, I’ve been collecting notes on Duvalier and Jules Oscar,” Nicolas said. “I have the evidence. It’s all in the book, but now—”

“Slow down, son. Please.” Jean-Jean fell in a chair. He was still holding the photo. He shook his head and lowered his voice as though someone might be listening at the door. “This is very dangerous, Nicolas. Are you prepared for what could happen?”

Nicolas picked up the notebook and approached Jean-Jean. He held it open for the older gentleman to see. He had hoped for help from Jean-Jean, his mentor. Georges was an old friend, yes, but Jean-Jean’s sour history with Duvalier had put him in a position of kamoken anba chal, a rebel in disguise, someone who actively spoke against Duvalier, if only in whispers, behind closed doors.

The man was like a father to Nicolas. After being accepted to law school in Port-au-Prince, Nicolas had sought an internship at the prestigious Cabinet d’Avocats with Jean Faustin, a judge who himself had started out as an attorney. That first day, Jean-Jean had carefully appraised Nicolas’s curriculum vitae, then studied his cheap, worn-out dress shoes and the glimmer of ambition in his eyes, before deciding to take the young man under his wing. And now here they were, in the successful protege’s beautiful library, surrounded by hundreds of books. Jean-Jean leafed through a few pages of the manuscript.

“What exactly do you plan on doing with this?” he asked Nicolas. “You’re thirty-five, with a beautiful family. You’re far too young to risk losing everything. You must not have thought this through…”

Nicolas’s shoulders were broad, and he towered over Jean-Jean, who stared at him with a combination of love and suspicion, like a man waiting for his son to confess to a serious transgression.

“I was hoping you could find a way to smuggle it to that friend of yours in France,” Nicolas said. “The editor? I have a mountain of research and evidence, things I can’t keep locked in my drawer forever. It’s only a matter of time before…”

He handed the notebook over to the old man, but Jean-Jean motioned for him to put it away. Nicolas froze. He’d expected shock, yes, but also that Jean Faustin would understand. What he hadn’t expected was dismissal. His mentor looked pale.

Nicolas took a deep breath. He was not giving up so easily.

“More sugar?” He reached for the cubes on the tray.

Jean-Jean shook his head, waving them away. “You know I can’t have that,” he grumbled.

In his distraction, Nicolas had forgotten Jean-Jean’s diabetes, which required his old friend to give himself insulin injections several times a day. Nicolas backed away and took a seat at his desk facing the two men in their wicker chairs. Their faces drooped—they hadn’t been prepared for this when they’d strolled in earlier. The shelf next to them held leather-bound books on civil and penal codes and a black-and-white portrait of the L’Eveillé brothers. Nicolas, dressed all in white, knelt at a pew holding a rosary next to his older brother. Somehow this image gave him strength for what he was going to say next.

“I have proof he ordered the arrest and execution of Dr. Jacques Stephen Alexis. No one will doubt it now. It’s just—”

“That’s the extent of your plan?” Georges looked at him incredulously. “Export an accusation to France and then sit tight? Like news of this won’t come back to hurt you?”

“Have you forgotten where you are?” Jean-Jean bristled. “If you get caught with this, the Baron’s spies will take you away.”

Nicolas looked down at his shoes, silently pressing his toes against the floor to control his frustration. “Which is precisely why I need it out of my hands.”

“And then what?” Jean-Jean asked.

“Are you trying to get us killed too?” Georges hissed. “And what about your family?”

“I realize it’s a lot to ask,” Nicolas said. “But I can’t just throw this out.”

“Of course not,” Jean-Jean said. “I was thinking a bonfire.”

“Help me, Jean! Or I’ll find someone who will.”

Jean-Jean’s voice burned with an anger Nicolas had never heard before. “Like who? That poor idiot who got caught at the airport smuggling in newspapers? Where is he? No one’s seen him since. Just for bringing in a few op-eds by foreigners! You are not prepared to handle this—”

“But I am prepared,” Nicolas started to argue.

Jean-Jean held up a silencing hand and turned toward Georges, who was now chain-smoking. “Talk some sense into the boy, Georges. What is it your friends at the ministry are calling writers these days? A danger to the Republic?”

Georges blew plumes of white smoke into the air. They curled into spirals and crashed against the art naïf paintings on the wall.

“He’s right, Nicolas,” Georges said. “To ask us to help you with this—it isn’t just madness; it’s callous disregard for everyone’s safety. You simply cannot expect us to release this information.”

“How can I not release it?” Nicolas said. “Who else will talk about it if not me? Are we supposed to go on pretending that Dr. Alexis just vanished into thin air? It’s all here for anyone who could possibly have doubts.” He grabbed another clipping from his notebook and held it up. “I have his signature approving the order to be carried out by the warden of Fort Dimanche.” He pointed at the photo in Jean-Jean’s hand. “It was Jules Sylvain Oscar who ordered his Macoutes to cut—”

“Enough!” Jean-Jean stood up and ran his hand over the thinning gray hair around his bald spot. “I’ve heard plenty.”

He tossed the photograph on Nicolas’s lap. The room fell silent.

Nicolas stood up and looked his mentor in the eyes. “You knew Dr. Alexis, didn’t you?”

“What difference does it make? And how the hell did you get this information, anyway? Who’s your source?”

“I can’t get into that right now,” Nicolas said.

“Bullshit!” Jean-Jean turned away.

The disappearance of Jacques Stephen Alexis four years ago, upon his return from Moscow and Cuba, had left Haiti bruised and drained. Yet another brilliant intellectual the regime had done away with, fearing the contagion of communism. Of course, it had never been proven.

“You need to slow down, approach this differently, and hope—” Georges paused. He looked uncomfortable, constipated. “Hope like hell this doesn’t leak. Who else have you shown this to? Who else have you told?”

“You said you wanted to see him toppled, didn’t you?” Nicolas yelled at Georges, who was lighting another cigarette. Georges brought his gold-ringed finger to his lips.

“You said you knew a guy who prints tracts and distributes them in the middle of the night,” Nicolas said. “Could he print this book in a compact format? This way it would be easier to—”

“Ah non!” Georges shook his head. “Be reasonable!”

“Jean-Jean?” Nicolas turned to the judge, who was staring at him through narrow eyes. “What about the editor you always visit when you travel over the border to visit your sister? I’m sure he’d be interested.”

Jean-Jean gazed back in disbelief. Nicolas waited, his heart racing. Finally, Jean-Jean shook his head. “I can’t believe you’d entertain that idea. What do you want me to do? Travel with a ticking bomb in my suitcase?”

Nicolas didn’t move. He didn’t dare. But he held his mentor’s stare.

“Help me get the book to him while I find my way out of Haiti. The whole world is going to want to read this. I’m not stupid enough to sit here and wait for them to arrest me. I have a plan. But for me to have any chance, the book needs to go out now.”

“They’ll kill you, you lunatic!” Jean-Jean yelled, and immediately caught himself. He peered out the window, but there were only breadfruit tree branches and rosebushes swaying in the evening breeze.

“I’m going to leave the country,” Nicolas reiterated, “and take my family. They won’t find us. Jean-Jean, if she’ll have us, we could go live with your sister in the Dominican Republic—me and Eve and the baby. We’ll hide there until we can figure out how to get to Europe and apply for asylum.”

“Are you really serious?” Georges asked. “Is this what Haiti has done to you?”

“It’s what Haiti is doing to all of us!” Nicolas snapped. “Come on, Georges! Give me a break. You mean to tell me your passport isn’t stamped and ready? You mean to tell me all those phone calls from your kids in Switzerland aren’t about figuring out how to get you out of here? Forever?”

Georges’s eyebrows met for a moment, but he didn’t deny the charge.

Nicolas turned to Jean-Jean. “And you, Jean? Tell me, you old patriot! No one loves his flag more than you, but you’re visiting your sister more and more. Before long, you won’t bother to come back. Tell me I’m not right.”

Jean-Jean tried to answer, but Nicolas cut him off. “I’m not judging you,” he said. “I don’t want to leave either. I love my home. I love my work. I want to be able to do that work without looking over my shoulder all the time. But I have a daughter now, and a wife who lost her whole family last October in that massacre of rebels.”

Nicolas took a deep breath. His friends were silent now, subdued by his outburst. He turned around, pulled out a drawer, and placed the manuscript and his notebook inside before shutting it.

“You know Eve and I had to go into hiding after her father and brothers were killed,” he whispered. “I can’t take the pressure any longer. When I lecture my students, I can feel myself on the verge of telling them that censorship is wrong, that education should never be compromised. This isn’t the Haiti I want my daughter to grow up in.”

The older men let an acquiescent silence settle over the room. Jean-Jean shoved his hands in his pockets. Georges looked at the floor between his shoes.

“It wasn’t always like this,” Jean-Jean said. “We’re better than this.”

He wrestled himself out of the chair, took a few steps forward, and rested his hand on Nicolas’s shoulder. “We’ve had a rocky political history, but never like this, no. Duvalier’s the worst devil of them all.”

A dog barked in the distance, as if in rebuke at hearing Papa Doc’s name spoken out loud. Georges flinched in his seat.

Jean-Jean squeezed Nicolas’s shoulder. His face was sullen. “Walk us out, will you? It’s almost curfew.”

Outside, the gardens hemorrhaged fragrances of rose and jasmine. Eve had potted every variety of fern and red ginger, dangled orchids from the branches of trees, and placed laurels and frangipanis at the entrance to soak the house in color.

The men stopped in front of Georges’s black Citroen. He and Jean-Jean had come together, and now they looked anxiously at their watches.

“Please tell Eve we’re sorry to leave in such a hurry,” Georges said. “Time is our greatest enemy these days.”

Nicolas said nothing. He needed an answer, and his friends were leaving without a promise or even giving him any advice. He watched them climb into the vehicle. Georges started the engine. The rumble interrupted the chirping of pipirit birds.

“Let me think about this, Nicolas,” Jean-Jean said, scratching his neck in thought. “I will come up with something, God help me!”

Nicolas met his mentor’s eyes, his heart swelling with hope. Georges coughed and glanced at the old man.

Jean-Jean lowered his voice. “I mean, I’ll see what I can do. But we will need a commitment from you, and a time frame.”

Nicolas’s eyes sparkled with gratitude. He opened the gate and let the Citroen roll out. Everything was quiet and still, and as Georges drove away, Nicolas watched the sun fall behind the mountains.