Читать книгу An Edible Mosaic - Faith Gorsky - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCooking Tips and Techniques

This section is meant as a guide for some of the most commonly used techniques in Middle Eastern cooking. As I learned how to cook, I was surprised that even a small amount of extra effort can make a huge difference in a finished product. Brining chicken, for example, requires minimal effort and you will be able to taste the difference from the first bite: not only is brined chicken more tender and juicy, but it tastes fresher and has less of a fishy flavor than non-brined chicken. This section also shows you that some kitchen tasks are much easier to do at home than you might have thought. For example, I used to buy blanched almonds at the grocery store before I realized how easy it is to blanch them at home (and it saves money too!). And there are other tasks that I did well enough (ahem, cooking eggplant) and was happy with the results, but wasn't very impressed by the food's flavor until I learned the proper way to handle it (like giving it a little time alone with some salt). Little tricks like these will transform your food from good to fantastic.

Blanching Almonds: Blanched almonds are frequently used as a garnish for both sweet and savory dishes. They are wonderful on top of puddings or as a garnish for other desserts, like Coconut Semolina Cake (Harissa) (page 130), or sautéed up in a little bit of clarified butter or olive oil, they add flavor and crunch to rice dishes like upside-Down Rice Casserole (Maqluba) (page 114) and Baked Chicken with Red Rice Pilaf (Kebseh) (page 96). Blanched almonds are commonly available at grocery stores, but in a pinch it’s good to know how to make them at home. There are four steps to the process: (1) place fresh, shelled (raw and unsalted) almonds in a heat-safe bowl; (2) pour in enough boiling water to fully cover the almonds; (3) let the almonds sit for 1 minute, then pour into a mesh sieve, rinse under cold water, and drain; and (4) hold one almond at the wide end between your thumb and forefinger and gently squeeze—the skin should slip right off. (Note: if your almonds aren’t the freshest, you can use a slightly different method to blanch them. Pour them into a saucepan, add enough water to cover, and bring up to a rolling boil. Boil 1 minute, then pour into a mesh sieve, rinse under cold water, and drain. The skins should slip right off.) Blanching can cause almonds to lose a bit of their crispness, as they tend to absorb water. To dry them out, pat them dry with paper towels or a clean kitchen towel, and then spread them in an even layer on a large baking pan. Let them sit in a sunny spot for a full day, or transfer them to an oven that has been preheated to 200˚F (95˚C) and then turned off. Once dried, store blanched almonds in the freezer.

Chiffonading Herbs: this technique is used to shred herbs into thin, confetti-like strips. The purpose of this technique is to keep the herbs as fresh and crisp as possible, with minimal wilting or bruising. For most salads that use minced herbs such as Middle Eastern Salad (page 47) and Colorful Cabbage with Lemony Salad Dressing (page 40), a regular mincing technique works perfectly fine, and for most cooked dishes that contain minced herbs, like Sautéed Greens and Cilantro (page 58) and Cauliflower Meat Sauce (page 110), i’ll go one step further and say that a Mincing Knife/Mezzaluna (page 16) does a decent mincing job. However, there are a few dishes where the integrity of the herb is of utmost importance and so chiffonading is the best technique; one such dish is tabbouleh (page 44). Before chiffonading any herb, wash the herb and let it dry completely (water can cause it to blacken quicker). To cut up large, flat-leafed herbs (such as mint, basil, and sage), pick the leaves off their stems and stack about eight to ten leaves; tightly roll the stack lengthwise into a cigar shape, then use a sharp paring knife to thinly slice across the cigar, creating little ribbons. Parsley is a bit more difficult to chiffonade since the leaves are smaller and more irregularly shaped; don’t let this deter you though, once you get the hang of it, it really will be quick work. The method for chiffonading parsley is described in the recipe for tabbouleh.

Cooking Dried Beans and Lentils: As a general rule of thumb, I use canned beans but dried lentils (which cook much quicker than dried beans) for cooking. Of course, there are a few recipes for which dried beans are noticeably better, such as hummus (page 79) and Falafel (page 81), and for those select few I take the extra time to cook dried beans. If you want to use dried beans be sure to plan ahead, since most should be soaked in cold water for 12 to 24 hours, during which time the beans will swell as they absorb water. (if you’re really pressed for time, here’s a trick that my mom taught me: add the [unsoaked] beans to a large pot and cover with water; bring up to a boil, boil 3 minutes, then turn the heat off, cover the pot and let the beans sit for one hour; drain and proceed with cooking the beans.) After soaking, drain the beans and add them to a large pot with fresh water; bring them to a boil over high heat, then turn the heat down slightly and boil until they’re tender, adding more water as necessary so that they are immersed, (the exact amount of time will vary depending on several factors, including what kind of bean you’re using, how old the beans are, and even the weather); this generally takes one to two hours for chickpeas. (Don’t add salt or acid—such as lemon juice, tomato, or vinegar —to the water as the beans cook, since these can cause the skins to toughen; instead, season the beans once they’re tender.) Also, during the cooking process, the skin on the beans will sometimes come off; you can pick through the beans to remove it if you want. This step is fairly time-consuming and is optional; I may or may not do it depending on how I plan to use the beans. However, i’ve noticed that when I take the time to pick out the skins when I make the hummus, I end up with a much creamier consistency. Here are the general equivalent measurements for canned and dried beans: 1 (approximately 16 oz/500 g) can of beans = 1¾ cups = ²⁄ ³ cup (4¾ oz/135 g) dry beans.

Cooking Eggplant: First things first, when you’re buying your eggplant, look for smaller fruits rather than larger ones, since they will usually be less bitter and have fewer seeds. Eggplant should be smooth and shiny, and feel heavy for its size. If it’s ripe, when you gently press a finger into it, the eggplant should give a bit but the indentation should spring back; if the flesh doesn’t spring back, it’s probably over-ripe and if it doesn’t give at all, it’s probably under-ripe. If eggplant is being roasted whole, such as for Roasted Eggplant Salad (page 44) or Eggplant Dip (page 64), it should not be peeled; other than that, peeling eggplant is based generally on personal preference. I usually peel larger ones and don’t peel smaller ones, but sometimes I partially peel them for a striped appearance. After peeling, slice the eggplant into about ¼ to ½-inch (6 mm to 1.25 cm) thick slices; salt both sides of each slice, place the eggplant in a colander, and put the colander in the sink for 30 minutes. During this time you will notice a brownish liquid seep out (this is normal), which will help reduce the eggplant’s bitterness. After that, rinse the eggplant under cold running water; gently wring it out, and then pat it dry. At this point, the eggplant can be deep or shallow-fried, or brushed with a little olive oil and grilled or broiled until golden on both sides. Prepared this way, eggplant is perfect for Fried Eggplant with Garlic and Parsley Dressing (page 53) or upside-Down Rice Casserole (page 114).

Cooking with Yogurt: Yogurt is often used to make wonderfully tangy, yet creamy soups like Lamb and Yogurt Soup (page 109) and sauces such as the sauce in Stuffed Squash in Yogurt Sauce (page 104). The only issue with cooking yogurt is that it has to be given a bit of extra care to prevent curdling. For starters, don’t use a fat-free yogurt, since a higher fat content helps prevent curdling; full fat is best but reduced-fat will also work. Making sure your yogurt is at room temperature when you’re ready to use it also helps. Use the amount of cornstarch and (sometimes) egg that are specified in each recipe, as these ingredients are added to both thicken and stabilize the yogurt. Lastly, yogurt should always be cooked gently (medium heat or lower is best), while being stirred constantly in one direction with a wooden spoon.

Frying Basics: Middle Eastern cooks don’t seem to shy away from deep or shallow frying, since many recipes— from Fried Eggplant with Garlic and Parsley Dressing (page 53) to Falafel (page 81) to Spicy Potatoes (page 57)— all contain fried components. If you follow proper frying procedures, food doesn’t absorb an excessive amount of oil; instead, you’re left with a crispy exterior and tender interior. When you fry, make sure to choose the right oil; in Middle Eastern cooking, good quality corn oil is typically used for frying, but any good oil with a high smoke point will work. The next point to consider is what vessel to fry in; if you’re deep-frying look for a large heavy-bottomed pot with deep sides (you can fill it up about one-third to one-half of the way with oil) and if you’re shallow-frying, a large skillet (preferably with a heavy bottom) will work (about ½ inch / 1.25 cm) of oil in the bottom of the skillet is usually perfect. Make sure the oil is up to temperature before adding the food; for most recipes, 350 to 375˚F (175 to 190˚C) is just right, and ensure your food is patted completely dry before adding it. When you (carefully) add the food, be sure not to overcrowd the pan. (this will drop the temperature too much, causing your food to be soggy and greasy.) when your food is cooked, transfer it immediately to a paper towel-lined plate to drain any excess oil; also, this is the best time to salt the food since it will be absorbed best (other than eggplant, which is salted before frying to reduce the bitterness; see Cooking Eggplant on page 11). A very useful tool for frying is the spider strainer (page 17) and also, something called a splatter guard, which is a circular mesh cover with a handle that is placed on pans when frying to prevent oil from spattering out. Of course, if you really don’t want to fry in the traditional way, “oven-frying” is also an option for most foods; in this method, foods are lightly coated in oil and cooked in a hot oven until crisp outside and soft inside. For a description of “oven-frying” as pertaining to cauliflower, see the recipe for Cauliflower Meat Sauce on page 110.

Hollowing Out Vegetables to Stuff: in Middle Eastern cuisine, about any vegetable is stuffed. A few favorites are tomatoes, small bell peppers, cabbage, grape leaves, small potatoes, baby eggplants, and marrow squashes (see Marrow Squash, page 120). If you can’t find marrow squash, zucchini is a good substitute; look for small zucchini, about 8 to 10 inches (20 to 25 cm) long that are as straight as possible, which can be cut in half so that each half can be hollowed out. Cabbage and grape leaves don’t need to be hollowed out; they are simply rolled up tightly with stuffing. tomatoes and bell peppers are easy to hollow out: just cut off the top where the stem is and scoop the insides out. To hollow out potatoes, eggplant, and marrow squash (or zucchini), you will need a vegetable corer (page 17). For marrow squash, zucchini, or eggplant, trim off both the stem and blossom ends. Hold the fruit in one hand and insert a vegetable corer into the center, gently rotating the fruit so it turns around the corer; remove the corer, set the pulp aside, and continue gently scraping the inside of fruit; continue this way until you have a shell about ¼ inch (6 mm) thick. For potatoes, choose medium-sized vegetables and peel them before you start coring; core them the same way you would eggplant, zucchini, or marrow squash, but leave the shell about ½ inch (1.25 cm) thick. The insides that are scooped out can be added to soups, made into dips, or omelets like the Zucchini Fritters on page 65.

Making Middle Eastern Salads: Salads are a huge part of Middle Eastern cuisine, as some form of raw vegetable is typically present at every meal. For the smaller meals (breakfast and dinner), maza platters usually contain large pieces of vegetables that are picked up and eaten with your hands: whole leaves of crisp Romaine lettuce along with sliced or chunked cucumber and tomato, whole green onion, and quartered white onion. For lunch (the largest and most formal meal of the day), vegetables are usually chopped neatly into salads and eaten as is or spooned on top of rice (if rice is present in the meal). The signature of a Middle Eastern salad in general and a Syrian salad in particular is the precision with which the vegetables are cut. Before being chopped, vegetables are cleaned by soaking them in a large bowl of cold water with a splash of Apple Vinegar (page 26); after this they are rinsed and patted dry. Tomatoes, cucumbers, and white onions are cut into a perfect dice. Green onions (scallions) are thinly sliced and fresh parsley and/or mint are minced with razor-sharp paring knives. Lettuce and/or cabbage are finely shredded into little ribbons. A tart, refreshing dressing, such as the Lemony Mint Salad Dressing on page 28, is mixed and the salad is dressed at the last minute right before eating so the vegetables stay fresh and crisp. As you can imagine, this process can take a while, especially if you’re cooking for a crowd; this is why many women use large utility boards, often taking the board to the parlor or guest room with a group of women so she can talk with visiting ladies (neighbors, friends, and family are frequent daytime guests) as she works. Also, most salads can be made ahead; just chop all the veggies and toss them together as normal, but wait to add the dressing until right before you’re ready to serve the salad.

Making the Perfect Pot of Rice: I remember when making rice was the bane of my existence. After watching my mother-in-law make rice effortlessly, I picked up a few helpful tricks that ensure perfect rice every time. Before you start preparing the rice, get out a saucepan or pot, preferably with a thick bottom (or use a heat diffuser) for cooking the rice. Rinse the rice under running water to remove any talc or excess starch; this will result in fluffier rice. After rinsing, soak the rice for 10 minutes; this makes the rice less brittle so it’s less likely to break while cooking, shortens the cooking time, and lets the rice—particularly basmati—expand to its full length. While the rice is soaking, put half a kettle of water on to boil. Drain the rice well after soaking, and then it’s ready to be toasted. Toast the rice in a little oil or clarified butter in the pot that you’re going to cook it in; it will start to smell amazingly nutty at this point. Add water. The exact amount of water you’ll need depends on a few different factors, including how old the rice is, the starch content (including how long the rice was rinsed for), how the rice was harvested and processed, the type of cooking vessel you’re cooking it in, the lid you’re using, temperature, humidity, etc.; generally though, I start with a little more water than the amount of rice i’m using. Then bring the rice up to a boil, cover the pot, and turn it down to very low. Let the rice cook until it’s tender but not mushy and all the water is absorbed (this takes about 10 minutes) without opening the lid; at this point turn off the heat and let the rice sit for 15 minutes. Uncover the rice, fluff it with a fork, and revel in its perfection.

Preparing Chicken: Most chicken recipes in this book require use of a whole chicken; this is generally the best bargain, and what is most commonly used in the Middle East. For most recipes, the chicken must first be butchered. To do so, remove the innards, giblets, head, and neck (most chickens can be purchased this way from the grocery store). Cut out the chicken’s backbone by first cutting down one side of it and then down the other; quarter the chicken so you have 2 breasts and 2 thigh/leg pieces, and then cut each breast into 2 pieces, leaving the wing attached. You will end up with 6 pieces total; if you prefer, you can also separate the leg and thigh so you end up with 8 pieces total. Cut away the wing tips and excess fat, leaving the skin on; rinse the chicken and pat it dry. The next step—soaking or brining—is optional but highly recommend. Brining chicken yields juicier, tenderer, and more flavorful result, and it also helps to refresh the meat, removing any “fishy” smells. To brine a whole chicken, butcher the chicken as described above, then put it into a large, non-reactive bowl. Add 1 tablespoon non-iodized salt, 1 tablespoon apple cider vinegar, 1 tablespoon fresh lemon juice, and 4 cups (1 liter) of lukewarm water to a large measuring cup with a pour spout; stir to dissolve, then cool to room temperature. Pour the liquid over the chicken, and then add enough cold water to cover, transfer to the fridge and soak 4 hours (or up to 2 days). Once it’s done soaking, rinse the chicken thoroughly under cold running water, pat dry, and proceed with the recipe. Now for cooking the chicken…typically in Middle Eastern cooking, when chicken is served with a meal containing a sauce and/or rice dish, like Roast Chicken with Rice and Vegetable Soup on page 90 or Baked Chicken with Red Rice Pilaf on page 96, the chicken is first boiled until fully cooked, and then deep-fried to crisp the skin. The one benefit I can see of this method is that you end up with homemade chicken stock as a by-product of boiling the chicken; however, since good quality stock or even stock cubes are commonly available at grocery stores, I prefer a simpler, one-step method that I think results in juicier, more flavorful chicken: roasting! to roast, preheat oven to 350˚F (175˚C) and arrange the chicken pieces in a single layer on a large baking sheet. Rub the top with a little olive oil, yogurt, and/or spices (each recipe will specify the quantities) and roast until the juices run clear when poked with a sharp knife, about 50 to 60 minutes. Once roasted, if you want the chicken to have more color, you can broil it for a couple of minutes. (My mother-in-law has recently started using a slightly different method: boiling the chicken as normal, but then placing the chicken in a shallow dish, rubbing the top with a little yogurt, and broiling it until it gets a little color. I think this method is pretty ingenious, but I still prefer the flavor and texture of chicken that has been roasted.) in the end, you can cook the chicken whatever way is easiest for you.

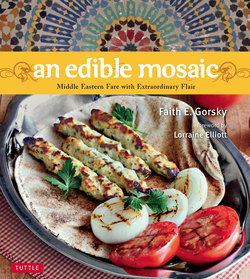

Putting Together Maza Platters: Maza can have several different meanings, but in this book i’m referring to a variety of different dishes on small plates, served together on one large platter. Usually food served this way is rustically eaten off the tray either with your hands or with flatbread for scooping. This style of eating is common for smaller meals (i.e., breakfast and dinner), and is also used to serve appetizers before lunch (which is the largest meal of the day) or as a snack. So, what goes on a maza platter? it can be anything you like! Breakfast platters may contain eggs (cooked any way), fresh herbs, sliced tomato and/or cucumber, Yogurt Cheese (page 73), Sesame Fudge (page 119), a variety of olives, olive oil, thyme Spice Mix (page 29), flatbread, and tea. For maza platters served at other times of the day, leftovers are perfect and vegetable dishes are abundant; i’ve seen many a maza with fried eggplant, like the eggplant made in Fried Eggplant with Garlic and Parsley Dressing on page 53 or a small dish of Okra with tomatoes in a Fragrant Sauce on page 55 or Spiced Green Beans with tomatoes on page 59. In general, maza platters don’t include meat, unless it’s leftovers that had meat, or occasionally a can of tuna, a tin of sardines, or a bit of sliced luncheon meat, such as mortadella or basterma.

Clockwise From twelve O’clock: Olive Oil, Fresh Mint Leaves, Flatbread, Yogurt Cheese (page 73), Assorted Olives, Chopped tomato, and Fresh Green Onion (Scallion); thyme Spice Mix (page 29) and Sliced Cucumber in the center

Clockwise From two O’clock: Romaine Lettuce, Baby tomatoes, Flatbread, tuna Fish, and Lemon wedges (center)

Using a Pressure Cooker: these days most of us are so busy that kitchen shortcuts have become indispensible; even my mother-in-law in Syria (a traditionalist in the kitchen) frequently uses a pressure cooker to save time. A pressure cooker is a special pot with an airtight lid and a vent or pressure release valve (newer models have more safety features and slightly fancier lids). So how does a pressure cooker speed up cooking? Food and liquid are put into the pressure cooker and the lid is sealed on top; the pot is then placed on a heat source. Once the liquid boils, the steam that would normally escape has nowhere to go since the pressure cooker’s lid is airtight; instead, the steam remains trapped and causes the pressure inside the pot to increase. As the pressure increases, so does the temperature at which the liquid boils, allowing foods to cook more quickly (foods cooked under pressure typically cook in about one-third of the time). In Middle Eastern cooking, foods with long simmering times (such as meat, beans, etc.) are well suited for pressure-cooking. (Note: Make sure to thoroughly read the manufacturer’s instructions before getting started.)

Coffee the Middle Eastern Way:

what is commonly known as turkish Coffee (Qaweh turkiyeh) is drunk all day long in the Middle East; it’s what you wake up to, what you drink as an afternoon pick-me-up, and what you serve to guests. (For more information, see turkish Coffee, page 139.) traditional Arabic coffee (called Qaweh Arabi or Qaweh Mourra) is generally reserved for a few special occasions, such as holidays, weddings, and funerals. Green coffee beans are roasted in a pan over a fire and then coarsely ground with cardamom using a large brass mortar and pestle. Water and the ground coffee are added to the pot used for making Arabic Coffee (see Middle Eastern Coffee Pot, page 16), and then placed on the fire to brew. Once the coffee boils, it is typically left to simmer for around 10 minutes, and then it’s removed from the heat and steeped for about another 10 minutes. At this point, other spices such as cloves may be added, but sugar and milk are never added. Dates may or may not be offered along with the coffee. A small amount of coffee—usually just enough to cover the bottom of the cup—is poured into a small cup without a handle called a finjan (which is about the same size as a demitasse cup). (A small but important note, coffee should be poured from a pot held in the left hand into a cup held in the right; it should always be drunk from the right hand.) Guests are served in the order of their importance and then the host serves himself last. Empty cups are handed back to the host; if the cup is shaken, it signifies to the host that the drinker is finished. If the cup isn’t shaken when it’s handed back, it signifies that the drinker would like more coffee. The first time I had this coffee was at a restaurant in Syria; I was quite surprised at its bitterness. I asked a friend about the coffee’s bitterness and he told me that it isn’t a matter of liking Arabic coffee. He said that in Middle Eastern culture, it’s just something you know you’ll taste a couple times a year.