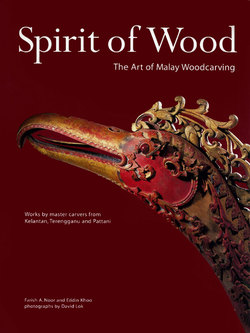

Читать книгу Spirit of Wood - Farish Noor - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Cult of Wood

Malay civilization has produced countless artefacts and works of art that are now part of the common inheritance of humanity. For centuries, the craftsmen and artists of the Malay world have created not only works of art of unsurpassed beauty and aesthetic value, but have also developed an aesthetic canon that is uniquely theirs. The world of Malay art and culture is therefore one that has to be understood through a lexicon of its own. Understanding the principles of Malay art requires knowledge of a specific semiotics, linguistics and philology that help us decode the hermeneutics of Malay art and culture.1

That such a hermeneutic approach is required in order to fully comprehend the depth of meaning found in Malay art is hardly surprising given that most developed civilizations have evolved a complex matrix of symbols, ideas, beliefs and values that have become ingrained in the rubric of societal relations commonly referred to as 'culture'. Malay art, which has evolved since the pre-Islamic period and which has absorbed elements, forms, ideas and values from a number of civilizational and cultural sources, ranging from paganism, animism, the Hindu—Buddhist era, the philosophy and culture of Islam, as well as influences from Europe, China and India, is itself no stranger to cultural innovation and development.

Despite the unending process of cross-cultural borrowing and interpenetration, Malay art still retains elements and features that are exclusive and unique to itself. Scholars such as H. Ling Roth (1910) have remarked on the particular symptoms and traces of Malay art which are not found elsewhere. This specificity is rooted in an internal logic that is confined to the Malay universe of meanings and values, and finds its expression time and again in Malay artistic work. Continuity is evident in the evolution of Malay art, and this testifies to the presence of a local genius at work.

The local genius of the Malay artist has manifested itself in a number of forms and mediums. The Malay world is known for its achievements in several artistic fields, including silver working, goldsmithing, weaving and embroidery, steel and weaponry, architecture and last, though not least, woodwork and woodcarving. All of these artistic developments occurred in the context of a society that evolved close to nature and lived in harmony with it. The development of Malay art, particularly after the coming of Islam, was very much focused on the relationship between human beings and the natural world around them. With the consolidation of Islam, there emerged the growing belief that through a deeper comprehension of the workings of nature, human beings could have a better understanding of themselves, their place in the universe and their station vis-a-vis their creator. Malay-Muslim art therefore relied heavily on natural materials and motifs and symbols that were derived from the flora and fauna around artisans. Rejecting the humanism and animism of the earlier pagan age, Malay-Muslim artists from the fourteenth century onwards began to focus their attention beyond the human form to the external world of nature.

SESIKU (BRACKET) (AR004)

Kelantan, 1830, cengal wood, 98.8 x 74.4 x 3.85 cm

Decorative brackets (sesiku) are an integral architectural element used to strengthen beams and rafters in large buildings such as palaces and mosques. This bracket was removed from the Istana Balai Besar in Kota Bharu in 1921 during renovations for Sultan Ismail's coronation. The style of carving resembles that on the gravestone of the consort of Raja Long Yunus, Che Ku Tuan Nawi, in Kota Bharu (see pages 60-1). The outline of the bracket is formed by Langkasukan motifs. Though the outlines of such brackets often remain constant, internal details may vary. The original red lime wash colouring on this bracket was uncovered below many layers of gloss paint.

The relationship between the human being and the other living elements of creation served as the new metaphor for humankind's existential condition and people's desire to acknowledge the 'other' in their lives. One of the first living entities to be incorporated into this existentialist drama was the tree. In this respect, the tree was a crucial element that stood between human beings and the natural world, and it served as the bridge that linked these two spheres.

Between Nature and Civilization: The Tree as a Liminal Entity

For the pagan Malays of the ancient past, the tree was literally the core of their universe. They believed that at the centre of the world was a great ocean, and in the middle of this ocean grew a gigantic tree called Pauh Jangi—the original, primordial tree of life that had stood since the beginning of creation. At the root of this enormous tree was a cavern called Pusat Tasek (Navel of the Great Lake). In this cavern lived a gigantic crab that emerged once a day. The movement of this gigantic creature caused the ebb and flow of the tides, the shifting of the winds and other atmospheric changes (Skeat, 1900). But it was the great tree Pauh Jangi that kept this pagan cosmos together, serving as the gravitational centre to this mobile and erratic universe.

Although such beliefs gradually lost their grip on the Malay mind-set, the respect and reverence for trees endured for much longer. With the coming of other religious systems, the Malay universe underwent several radical changes and revisions. The tree was gradually displaced and relocated to the margins of the Malay world, but it remained a crucial element in the cosmology of the Malay people. With the coming of Hinduism, Buddhism and, finally, Islam, the Malays began to view the world differently. But the tree remained fixed in their perennial mind-set.

The tree belonged to nature, and by extension, to the rest of creation. It cannot be understood in isolation, as it has always been part of a greater, harmonious whole that extended beyond its immediate form. The Malays viewed the tree as one of the fundamental symbols of life, creation and nature, knowing that it was one of the axial points in the cosmic drama that was played out before them. Trees were therefore an element of nature that played a crucial role in the development of Malay society as well as its aesthetics, philosophy and pseudo-sciences. But it also had to be well understood before it could be brought into use. This, however, was not such an easy or straightforward process, for the tree was not like any other element of nature that could be easily domesticated and utilized at whim. To the mind of the traditional Malay, the tree was also a liminal entity that stood in between two worlds—that of nature and that of human civilization.

The scholar Clifford Geertz (1993) once remarked that the moral and epistemological universe of the peoples of the Malay archipelago was divided into two mutually exclusive realms. On the one hand, there was the outer world of nature and natural forces, the environment of liar (wild) and kasar (rough). Conversely, there was the batin (inner) world of civilized human beings, the realm of halus (refined) and sopan (cultured). The division between the world of raen and the natural world without was drawn along the lines of this frontier between agonistic, primal nature and the civilized,2 the wild and the cultivated, the amoral and the ethical.

The Malays understood that their civilization was an artificial social construct that had to be protected and reproduced. Order in society was maintained through a complex network of social values and norms, and kept in check by the hierarchical mode of government that was typical of feudal communities. Yet the fabric of this fragile social drama could be torn asunder should the forces of nature be allowed to intervene in the affairs of men. The introduction, cultivation and reproduction of social, political, moral and aesthetic order was therefore of primary importance in the setting of traditional Malay settlements. One of the ways this sense of order was maintained was via the incessant struggle of keeping the forces of nature at bay. For the Malays of the archipelago, the forests that encircled their riverine and coastal settlements were actually barriers to their movement and freedom. While the sea was the open plain where they roamed and ruled, the forest was the insurmountable obstacle that kept the Malays perpetually corralled by the forces of nature. This geographical factor explains why the Malays viewed the forest in the way that they did.

The forest that surrounded the Malay world was an unknown, mysterious and at times impenetrable space. In its dense, humid and dark undergrowth, the forces of nature ran riot. Demons and ghosts lurked within the forest, inhabiting the trees and swamps, forever on the lookout for wandering human beings who had strayed too far from the protective confines of their homes and villages. For the people of the archipelago, the forest was, at best, a place where one's character could be put to the test, and, at worst, an infernal green hell where one ultimately became the meal of predators and foul spirits. Southeast Asia abounds with tales of heroes who had to undergo their trials in the middle of the foreboding forest.3

What was worse, the natural environment of the forest also tended to encroach onto the world of men and their civilization at every given opportunity. Should the borders of civilized Malay society recede, the creeping tendrils of the natural forest would immediately advance to fill the void. The forest was a stark contrast to the orderly world of the Malays, which was governed by norms and protocols of religion and civilized society, and the Malays could not help but wish to keep these natural forces at bay. George Maxwell (1907) described the Malay view of the forest thus: 'The forest envelopes their homes and their lives; but the more they explore it the more they know that it is a world apart. That it is so near and extends so far adds to its majesty and terror.'

An early 20th-century jungle scene in central Malaya taken by the Sumatran-based photographer C.J. Kleingrothe. It illustrates the lush natural environment in which the Malays of the 18th and 19th centuries lived. Photograph reproduced by permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

The Malays knew that whenever they entered the forests they were trespassing into another realm which they were not the masters of. Therefore, they prepared themselves with all manner of charms and esoteric knowledge (ilmu) that would be used to keep the hidden forces of the forests at bay. When they ventured into the jungle in search of wood or provisions, they were careful to begin their expedition by first hailing the spirits of the forests. They would read out certain time-tested charms such as the one below. Such charms or mantras were designed to ensure that no harm would come to the individual or his family and community as a result of this act of transgression into the unknown. Yet, between the known world of men and the unknown world of the jungle, there stood one common element that was shared between the two: the tree.

It was, in fact, the tree, one of the most vital elements in the natural environment, that kept the forces of nature in check. The tree was magical, but far from sinister. For it was the tree that provided the Malays with the defences and fortifications that protected their settlements and towns. The walls and palisades that were made from the trunks of trees and from bamboo were the barriers that kept out the numerous threats from the world of men and nature. Both invading armies and wild beasts (not to mention ghosts and forest spirits) were thus kept at bay.

| Assalamualaikum, | Assalamualaikum, |

| Aku datang ini bersahabat sahaja, | I have come in peace, and friendship, |

| Sahaja nak mencari hat kebidupan, | Come to seek my livelihood, |

| Janganlah engkau mengharu-hara aku, | (O ye spirits) please do not harm me, |

| Dan anak isteri aku, | Or my family, |

| Dan rumah tangga aku, | Or my home, |

| Dan segala kampung halaman aku, | Or my village and community, |

| Aku yang nak tumpang sababat ini, | For 1 count on your good will, |

| Mintalah selamat pulang balik. | And may you let me return safely. |

The tree was also the vital source that provided so much material for the daily maintenance of civilized Malay life. Wood was the natural element that kept Malay society together, literally. It provided them with houses, and within those houses, walls. (Thus the tree not only kept out the forces of nature, it also served to ensure that the existing social relations within this compartmentalized society could be maintained as well.) Trees provided the Malays with tools to work with, to farm with, to write with, to eat with and to fight with. It was, in short, the singular natural element upon which all of Malay civilization depended. Civilization, as the Malays knew it then, was almost impossible without this natural element. However, the Malays never forgot the fact that the tree also came from that chaotic and uncontrollable world of natural forces. Its presence in the midst of human society signified the penetration of nature into the world of men. As such, its status and role in the context of Malay civilization was always an ambiguous one.

The tree was the boundary marker that denoted the distinction between the kasar and the halus, the jungle and the settlement, the chaos without and the order of things within. It was therefore accorded the respect and awe that was due to it. And even when it was brought within the purview of human civilization as a resource and tool, it maintained its aura of mystery as something that was originally beyond the pale of humanity. Like that other vital natural element, fire, the tree was something that was necessary for human survival, but it needed to be kept under control. Thus the tree became, and remains, a curious totem or fetish of some unknown and mysterious force of nature. The belief in the semangat, or vital force', of nature and of trees, in particular, ensured that the Malays' attitude towards trees and wood was a carefully regulated and circumscribed one. The tree was so highly esteemed because it provided the Malays with one of the most indispensable elements used to build the Malay world: wood. Malay kingdoms, as we have seen, were dependent on wood in every respect. Thus, the possession and utilization of wood, and good wood, in particular, became part of the Malays' expression of largesse, power and civilization.

In the use of trees for wood and woodcarving, however, the Malays were particularly careful not to upset the natural equilibrium that maintained the balance and harmony between the world of men and nature. Malay woodcarving thus evolved a complex and advanced code and hermeneutics of its own, and eventually reached the status of a fine art that ranked as high as any philosophical system that had been developed by the Malay mind.

Cengal (Neobalanocarpus heimii), a tree of the deep forest, was domesticated in the 19th century and planted in the compounds of wealthy families to provide a ready source of timber. A hard, durable wood, resistant to insect attack, it is used for almost all structural elements in a building, but is also suitable for decorative panelling.

HILT, KERIS TAJONG (KW109)

Kelantan, late 20th c., kenaung wood, 16.5 x 15.25 x 5 cm

The sharply uptilted nose, the eye ornamentation and the strong lines of the jaw and crown combine to convey an aggressive quality in this highly ornamented hilt. The cup supporting the base of the hilt, called a pendokok, is made of silver, ornamented with pucuk rebung (bamboo shoot) and telurikan (fish egg) motifs. Carved by Nik Rashiddin Nik Hussein.

The Spirit of Wood in Malay Cosmology

For the Malays, trees and wood have never been mere commodities. Throughout the centuries, the Malays have developed a great respect for trees in general, and there are many recurrent motifs and symbols still in circulation in the Malay world that testify to the importance of trees to the Malay mind-set. Prior to beginning any performance of shadow puppet theatre (Wayang Kulit), the audience is presented with the static image of the great tree of life itself, the pohon budi, which represents the primordial tree that has stood from the beginning of time and whose branches and roots reach out into the infinite. To the left and right of the tree stand the opposing ranks of characters, good and bad. The drama that follows takes place within a moral and epistemological universe that is understood by the Malay mind-set: one where the forces of good and evil are constantly in conflict with one another, yet bound in a cosmic equilibrium where nature finally reigns supreme. The image of the great tree of life that is seen in carvings, shadow puppets, weavings and the like all indicate the extent to which the cult of trees had become deep-rooted in the Malay world.

On the exoteric level of life in the profane world, wood was an invaluable material that the Malays could not do without. The success or failure of their kingdoms depended on it, and the Malay world was necessarily one that was integrated with the rest of nature. But this reliance on wood as an enabling, empowering and life-sustaining resource was not merely a relationship that was acted out on a profane and material level. The cosmology of the Malays has always been one that was predicated on the division between the seen and the unseen, the material and the metaphysical, zahir and batin. This duality is reflected in the Malays' understanding of everything that came into the orbit of the Malay universe, which included the natural world as well. As Malay civilization developed, so did its understanding and appreciation of wood itself. By and by, Malay civilization evolved what can be termed a 'cult of wood', which invested the material with a plethora of hidden, esoteric meanings and values. One of the most important concepts in this unseen universe was the notion of semangat kayu. Today, there are several obstacles hindering our understanding of this complicated term. Foremost, we live in a modern age where rationality and positivism hold sway and where all things metaphysical are deemed as mythical, fantastic, preposterous or, at best, incomprehensible. How, then, can we understand the world of the Malay woodcarver, for whom the semangat of kayu was a perfectly tangible, sensible and comprehensible phenomenon?

The hilt of a keris tajong employing Langkasukan motifs on the body. Drawing by Nik Rashiddin Nik Hussein.

The tree of life (pohon budi), a leaf-or tree-shaped puppet carved from skin or leather which opens and closes all performances of the shadow puppet play (Wayang Kulit). It is sometimes also utilized during a performance as a stage property to represent a tree, a forest or a mountain. From the collection of master puppeteer Pak Dollah of Kelantan. Photograph by William Ha raid-Wong.

JEBAK PUYUH (QUAIL TRAP) (FL010)

Restored in Kelantan, late 20th c., angsana wood, bamboo floor, ivory door, ribu-ribu ribs, kapas binding, 33.4 x 30.8 x 23. 1 cm

Restored by Nik Rashiddin Nik Hussein, this old quail trap features a new front of angsana wood and ivory. Bunga tanjung motifs decorate the panels flanking the door. Leaves of the saga kenering, a type of creeping plant with black-spotted red beans, are used to form the gunungan. Two mythological sea monsters (makara) with ruby eyes are carved on the stepping board which triggers the net trap when a bird alights on it. The original basketwork cage (not visible) is very finely woven. (See also pages 100-3.)

The ketam guri motif used on the gunungan of the mosque pulpit on pages 26-7. Drawing by Norhaiza Noordin.

Petals of the bunga teratai (lotus) form the decoration at the foot of the grave of Che Ku Tuan Nawi at Makam di Raja, Langgar, Kota Bharu (see pages 60-1).

The concept of semangat serves as our starting point. Semangat has been (sometimes erroneously) translated as 'spirit', 'life force', 'soul' or 'essence'. None of these translations is entirely correct. An understanding of the concept of semangat first requires an understanding of the cardinal concepts of Malay cosmology itself. Scholars like Skeat (1900), Maxwell (1907), Endicott (1970) and others have attempted to construct a rational typography of concepts and values found in Malay metaphysics. Although there remains much work to be done to fully enumerate and classify the components that make up this manifold universe, we are now better able to speak about the hierarchy of concepts and values that make up the order of knowledge in the Malay metaphysical system at least.

From the Malay point of view, the universe is made up of a myriad of elements and objects that all come from one common source, the Creator itself. Mere existence in the world is already a miracle that testifies to the presence of a Creator and the link between creation and its Creator. Even a speck of dust owes its existence to this point of origin and prime mover of all things. Everything that exists, living or inanimate, bears the mark of the Creator in some way or other. This understanding of the process of creation, and of the link between human beings and the Creator, had existed even in the pre-Islamic era, but with the coming of Islam it was revised and developed further under the rubric of the concept of Tauhid, or the Unity of God.

The most rudimentary trace of this link to the Creator is what Malays refer to as the semangat or the 'vital force' of all things. It is a form of primal energy and vitality, invested in all things that are created as a result of the act of creation itself. It resides in all things that exist, and it disappears only when the object it belongs to is finally reduced to non-existence or non-being. At the most fundamental level, all things possess semangat to some degree or other.

Semangat is, in turn, linked to two other vital forces: nyawa (breath of life) and run (spirit of life). Living things possess the latter two elements while inanimate objects possess at least semangat. Human beings possess semangat, nyawa and ruh, the combination of which bestows man with rational agency, reflective intellect and creativity. It is also this that allows man to think and to realize his station in the universe, and through this knowledge to try to come to a better and more direct understanding of his relationship with creation and the Creator. Other living things may possess semangat and nyawa, but lack the intellectual and emotive capacities of human beings that allow for reflection and moral consideration. In the universe of the Malays, there are numerous lesser evolved spirit entities that may well react and interact with human beings, but without the moral considerations and deliberation of rational agents. At times they appear as naively benevolent, while on other occasions they manifest themselves as amoral malevolent forces bent on mindless destruction and violence. Endicott (1970) has noted that for the Malays, living trees are of particular importance as they often serve as an abode for such spirits, good or bad.

CEILING PANEL OF PULPIT (RT019F)

Surau Langgar, Kelantan, 1874, cengal wood, 21.8 x 21.8 x 1.29 cm

This small panel from the ceiling of a mosque pulpit (mimbar) comprises entwined stems carved with Langkasukan motifs. The carving style is the same as that on the tomb of Che Ku Tuan Nawi (pages 60-1). The outline of each corner takes the shape of a lotus bud or stupa.

The living tree is therefore of particular importance to the Malays. In the past, they regarded trees as being hosts for spiritual entities and forces that were capable of interacting with the world of men. Trees were the homes of spirits, and they became the focal point of devotional rituals (puja) which were directed to the spirits contained within them. Malays regarded some trees as being particularly powerful and endowed, and the cult of trees and wood emerged as a result of this deeper understanding and appreciation of the tree as a key element in the configuration of the esoteric and exoteric Malay world. There evolved an adab of trees—a correct way of dealing with them—and Malays learnt how to speak, communicate and relate to trees in a way that was unique to them. Boys, from the time they were young, were taught to recite special prayers (doa) when entering a forest, to ensure that the trees would protect them and that they would not be accosted by any malevolent spirits that might be lurking in the wilderness. Up until today, these beliefs endure and there are still many of those who feel that certain trees such as the kemuning (Murraya paniculata) and the waringin (banyan) host powerful spirit entities that should not be provoked or offended unnecessarily.

GUNUNGAN OF PULPIT (RT019A)

Surau Langgar, Kelantan, 1874, angsana and cengal woods, 148 x 69 x 20 cm

Depictions of a gunungan are often placed over mosque pulpits. Carved following the natural curve of the wood, stems of the ketam guri are here treated like ropes woven around flowers of the same plant. An inscription from the Koran forms part of the notched and curving lintel, reflecting the essence of Malay design, where alternating convex and concave curves represent the unity and balance of life. This fine carving (see also pages 64-5) is on loan to the Kandis Resource Centre from Surau Langgar, Kota Bharu.

KORAN (RT005)

Kelantan, late 18th-early 19th c.

The opening pages from an early handwritten and illuminated Koran. Gunungan motifs encase the calligraphy on all sides. The corners are decorated with rosettes of daun sesayap, a motif described as a wing-like leaf also known as daun Melayu, and bunga tanjung.

Wood, on the other hand, possesses only semangat. After the death of the tree, the spirit force of the living organism often leaves it for good in search of other hosts. (Only in rare cases does the spirit choose to remain in the wood, in which case it becomes highly prized, revered and, at times, feared for its inherent spiritual power.) Yet the semangat of the wood endures, as it still bears the traces of its Creator and the miraculous event of creation itself. This semangat of wood also happens to be the one element that is shared in common with human beings and, in particular, the wood-carver, who seems to understand the wood he works with. It therefore serves as the crucial bridge that brings together the woodcarver and the wood he prizes.

The semangat of wood is therefore of prime importance to the Malay woodcarver as it is the sole element that is intrinsic to the wood itself. It is a crucial element to both the existence and use of wood. Traditional woodcarvers of the past believed that it is the semangat contained within the wood that determines its beauty, the grain and lustre being directly related to the semangat forces contained within. (The stronger the semangat, the more lustrous, beautiful and flamboyant the grain.) Different types of wood have different types and levels of semangat contained within them.

Both the kemuning (Chinese myrtle, Murraya paniculata) (above) and the nangka (jackfruit, Artocarpus heterophyllus) (below) are considered to have a high spiritual quality (semangat). Wood from the root and lower trunk of the kemuning is highly valued for its coloration and grain, and is used for keris hilts and sheaths. The nangka is light and resonant and is often used for musical instruments.

It is also the semangat of the wood that determines the proper use and utility of the various types of wood. Some with particularly strong semangat contained within them are better suited for nobler tasks, and are thus used to carve keris hilts, ceremonial objects, gates and doors, while lesser woods of lower semangat are kept for everyday use. The Malays' world of wood and woodcarving is therefore circumscribed by what can be called 'the economy of semangat', a complex system made up of the various factors that determine the accumulation, reproduction and loss of semangat of the wood itself.

The semangat or vital force of trees is directly related to their place in the natural order of things. All trees and all types of wood possess semangat. But different trees have different levels of semangat simply because they grow in particular places where semangat forces may be high or low. Like human beings whose semangat depends on the food they eat, the place they live in, the work they do, the semangat of wood is very much linked to external environmental factors as well. The environment has always been a crucial factor in the economy of semangat: The semangat of trees and various woods is directly related to the way in which the trees grow. Some types of environment and climate are thought to be particularly good for trees, and add to the semangat of the wood:

• Certain types of soil are important in determining the level of semangat found in wood. Black soil with some traces of sand was, and still is, thought to be particularly good for certain types of trees, such as the kemuning. Plots of land that were close to the sea and human settlement, with hills or mountains in the background, were also thought to be particularly good areas for harvesting wood harbouring strong semangat properties. This was because the trees were growing in areas where life forces were being generated (from human settlements and human activity) and this, in turn, nourished the semangat in the trees themselves.

• Hills and mountains are also regarded as being particularly good for producing trees imbued with strong semangat. Trees that grew on slopes and at higher altitudes were thought to have stronger semangat than those growing on the flat. In the past, Malay rulers and nobles would often reserve certain plots or areas on hillsides for their private cultivation of certain trees for their own specific ends.

• The sun, which is a source of vital light, heat and energy, is also a major source of semangat. The rays of the sun are thought to strengthen the semangat of a tree. The earliest woodcarvers believed that the best part of the tree was the one that faced the rising sun (that is, the part of the trunk that faced eastwards). The wood on this side of the trunk was thought to be of better quality and have stronger semangat, for the simple reason that it had received more early morning light that was purer and stronger.

Certain types of trees and wood also possess stronger semangat. Woods with strong and pronounced grains (coreng), stripes (jalur), ripples (kerinting) and colours (pela) are said to have stronger semangat properties. Such grains are often found in woods that have a core (teras) in them; indeed, trees with cores in their trunks are regarded to be of particularly strong semangat. It is evident that for the Malay wood-carver, it is the semangat of the wood itself that determines the particular characteristics of each type of wood, and not the other way round.

PINTU GERBANG (ENTRANCE GATE) (AR001)

Kelantan, mid-19th c., cengal wood, brass handles and hinges, 351.5 x 274.5 x 13 cm

A gateway built for a former Prime Minister of Kelantan (see pages 80-1).

The bongor (Lagerstroemia speciosa) (above) and the angsana (Pterocarpus indicus) (below) both have decorative grains which make them highly suitable for keris sheaths. When polished, the bongor has a striped appearance, described as jalur. In contrast, the angsana, a wayside flowering tree, possesses a subtle grain which when polished gives a rippled effect, known as kerinting, much like watered silk.

Types of Wood Used in Malay Woodcarving

Literally hundreds, if not thousands, of types and species of trees are found throughout the Malay archipelago. But while all trees produce wood, not all wood is of value or use to the traditional Malay woodcarver. Despite the variety of material found in abundance all around him, the woodcarver does not have complete freedom to determine the design of his work. Ultimately, he is merely a servant (abdi) to his art and its rules and norms. He is not the one who will decide what the finished product will look like, despite his initial plans and his good intentions. It is the wood itself that determines how it will be used. This has always been the case in the woodcarving tradition in Southeast Asia. Similar philosophies are apparent in the woodcarving traditions of East Asian countries such as Korea and Japan, and are also prevalent throughout the Indian subcontinent.4

The form, pattern and grain of the wood will ultimately decide how and where it will be employed. This is because each type of wood has a character of its own, and it is this character that determines how it will best be used. Some patterns and grains are better suited for carving three-dimensional objects such as keris handles, while others are more suited to two-dimensional surfaces such as walls, decorative panels, furniture, doors and gates. (Even within a house, different types of wood will be used for different parts, depending on the latter's importance.) In classical Malay wood-carving, one often encounters unique pieces where the carver has deliberately ornamented his work in such a way as to enhance the grain and pattern of the wood, at the same time relegating his own carvings and adornments to a secondary status.

The most popular types of wood that were, and still are, commonly used by Malay woodcarvers include a number of hardwoods:

• Kemuning (Murraya paniculata, sometimes known as Chinese myrtle), a honey yellow hardwood endowed with a beautiful flame-like, luminescent grain running through it. Kemuning is also blessed with stripes as well as the quality of chatoyance (renek), or the ability to change its lustre. This is the king of woods for most Malay woodcarvers of the traditional school. It is highly prized in Malaysia, in particular, where its colour is thought to complement the gold brocaded cloth known as songket, another artistic tradition of the east coast states of the Malay Peninsula. This wood is often used for sculptures and keris sheaths and handles, and is so highly prized that it is never used for furniture or construction. Antique keris sheaths made of kemuning were rarely covered with silver or gold for additional decoration, as the beauty of the wood was regarded as being impressive enough by itself.

• Kenaung or kemung (Diospjros ebenum), often referred to as ebony, an extremely expensive black wood which is used for making keris handles. Its black tones add a touch of elegance and nobility to the keris handles that are made out of it. It remains a favourite among keris collectors who prefer the unstated elegance of monochromatic woods to the more outlandish and exuberant patterns found in wood elsewhere in the archipelago. This wood is becoming increasingly rare.

• Angsana or sena (Vterocarpus indicus), a deep orange-gold hardwood, which is sometimes used for making keris sheaths, but never keris handles. Woodcarvers regard it as the most suitable wood for traditional Malay furniture and it is also quite popular for house construction.

Carpenters working by the river in Kelantan at the end of the 19th century. Newly felled tree trunks were floated downriver to a processing shed where they were cut into planks to facilitate transport by the small, narrow boats that plied these rivers. Photograph reproduced by permission of the Syndics of the Cambridge University Library.

Other woods known for their particularly strong semangat include medang hitam (Litsea myristicaefolia) and nangka (jackfruit, Artocarpus heterophyllus). These woods were often employed in the construction of the ceremonial Burung Berarak, a mythical giant bird which was often paraded during important festivities and state rituals in the northern kingdoms of Pattani and Kelantan. They were also used in the production of masks (topeng), another important cultural totem in the world of Malay art and cultural performances. Similar requirements held sway in other parts of the Malay archipelago, especially in Java and Bali, where masks and other sacred objects for public rituals were deemed important enough to be given individualized treat-ment and were made of special materials.5

Malay architects and builders have also always harboured preferences. Their favourite woods include jati (teak, Tectona grandis), cengal (Neobalanocarpus heimii), and merbau (Intsia palembanica). All are black to brownish in colour and so dense that they can blunt even the hardiest of carving instruments. These woods are thought to be particularly good for constructing the beams and pillars of Malay houses as they are extremely durable and resistant to infestation. The other parts of the house are often made from different types of lesser woods, such as balau (Shorea spp.), resak (Vatica spp.), perah (Elateriospernum tapos) and sepetir (Sindora spp.).

Other popular and commonly used woods include:

• Gaharu (aloe wood, Aquilaria malaccensis), a pitch black, shiny wood which is often thought to have both spiritual and medicinal properties. It is often used for keris handles in the other parts of the archipelago.

CEREMONIAL BED FRAME (RT006a)

Pattani, date unknown, nangka, angsana, merbau and teak woods, 205.18 x 215.4 x 182.1 cm

The frame shown here is the front section of a royal four-poster bed reputed to eject any commoner who attempted to sleep on it. The bed takes the form of a traditional Chinese wedding bed with rails, subtly curved and notched in the Malay style, and panelling around three sides. The fourth, open side of the bed contains delicate tracery composed of bunga kerak nasi flowers and leaves and daun sesayap edged with delicate ribbons almost resembling bed curtains. The front of the massive base is decorated with kerak nasi leaves. The legs at the back are carved with a similar curving outline but are devoid of ornamentation. A top frame, designed to support a mosquito net, is also moulded and painted. The bed appears to have its original scarlet and indigo colours. The carvings are all richly gilded.

The merbau (Intsia palembanica) (above) is a reddish hardwood often used instead of cengal in building. The halban (Vitex spp.) (below) is a small tree commonly found growing next to rice fields. Its wood, which is dense, heavy and resistant to rot, is widely used for making domestic artefacts.

• Cendana (sandalwood, Santalum album) which is prized for its fragrant scent and is often used for both sculptures and carvings, as well as for medicinal purposes.

• Gemia (Bouea microphylla), a reddish hardwood which is often used for making keris handles and sheaths but is not used for furniture.

• Setar (Bouea macrophylla), a reddish-brown hardwood that is used for keris handles in the Malay Peninsula but for little else.

• Celagi (Tamarindus indica), known locally as asam jawa, often used for the handles of parang (cutting knifes).

• Halban (Vitex pubescens), a brownish to dull grey wood.

• Vauh hutan, a dark red wood that is sufficiently hard to be used for keris handles.

• Bongor (Lagerstroemia speciosa), which is reddish-brown in colour.

• Ketengga (Memillia caloxylon), a yellowish-brown wood which, like bongor, is only used for making keris sheaths but never keris handles or furniture. Nor is it used in the construction of houses and other buildings.

In other parts of the Malay archipelago we come across other woods, such as the deep brownish tajuman (Cassia laevigata willa), the sawo (Achras zapota), the trembalo (Djsoxylum acutangulum) and the tomoho or pelet (Kleinhovia hospita). These woods are very popular in Java, Bali and Sumatra. Needless to say, like their counterparts in the Malay Peninsula, the woodcarvers of Indonesia have evolved their own complex (and at times confounding) belief systems surrounding these woods. The most important observation that needs to be made is that the woodcarvers of the Malay world share a common understanding and respect for the material they work with. For the wood-carvers of the archipelago, there are a number of cardinal rules and protocols to beobserved and one of these is the belief that the best wood should be reserved for the carving of sculptures. It goes without saying that the best sculpture in the Malay world is found in the carving of keris hilts (hulu keris).

While woodcarvers in Java or Bali seem to favour woods of contrasting colours and flamboyant grains, among them tomoho/pelet and trembalo, Malay woodcarvers of the peninsula arc more partial to woods such as kemuning and kenaung because of their subtler coloration and patterns.

All of these Malaysian woods are thought to possess semangat properties in various degrees. The magnificent kemuning, in particular, was thought to have strong semangat, and the adab of finding, cutting and working the kemuning wood formed a universe of its own.

In the past, the kemuning was regarded as the tree of the Dewi (Primordial Goddess), and it was reserved for the use of kings and nobles. It was so highly sought after that it was almost impossible to find the tree growing naturally near any human settlement, for its discovery meant that it was almost certain to be cut down. The tree was sometimes referred to as 'the tree with a hundred and one uses'. Woodcarvers would wax eloquent about its merits: its grain did not destroy the quality of their work and did not distract the eye of the admirer; the wood was hard enough to be used for the hilts of weapons, yet light to the touch and easy to work. Many varieties of kemuning were used, including the kemuning limau (lemon yellow kemuning), kemuning buah lada (peppercorn kemuning) and kemuning buah kekut (cherry fruit kemuning).

Sultan Muhammad V of Kelantan and his son outside the gates of the Balai Besar, Kota Bharu. The fine pemeleh pintu over the doorway is in the form of a gunungan, with foliate sulurbayu, and is protected from the worst of the elements by a shallow roof. The waistcloths of the Sultan and his son are looped over the hilts of their keris as protection against any ill-effects of the camera. The photograph was taken by Sir Frank Swettenham during his visit to the Kelantan capital in October 1902, when he tried, unsuccessfully, to persuade the Sultan to join the Federated Malay States. Photograph reproduced by permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

The best kemuning wood came from trees that had died naturally. Woodcarvers might spend weeks, or even months, in search of such treasure in the deep jungles of the peninsula. A find in the forest was the woodcarver's equivalent of discovering a gold mine, and the whereabouts of such a prized hoard would be a closely guarded secret. (This is hardly surprising when we consider that in the past samples of the best kemuning were thought to be more valuable than gold.)

After the discovery of a stand of kemuning, the leaders of the community (often the Raja himself and his ministers and religious functionaries) would engage in long periods of consultation. If they felt that the trees could not be protected from poachers or thieves, they would then decide to cut the trees down themselves. They would begin by identifying a suitable time for felling them. They would also take into consideration criteria such as the location of the trees before felling began. Woodcarvers preferred kemuning trees that were growing in hilly areas where there were plenty of rock formations, as it was believed that this would force the roots of the tree to bend and twist in a number of ways, thereby creating the grain that the woodcarvers so desired. Sometimes the trunks of the trees would be 'scarred' by hacking them with cleavers (parang) and then left to 'mature' for a few years before the trees were actually cut down. This process of scarring the tree trunk was deemed necessary not only to check on the quality of the wood but also to make the wood 'react' to the scarring process. It was thought that such deliberate scarring would cause the trunk to grow in a more erratic and confused manner, thereby adding to the flame-like grain of the wood itself.

Four pisau wall handles. Drawings by Norhaiza Noordin.

The pisau wall is the woodcarver's main carving tool in the Kelantan-Terengganu-Pattani region. Nowadays, such knives are often made using blades from cutthroat razors imported from Europe. The form is carved by a scraping action of the pisau wall after being roughly shaped by the chisel or adze. These knives were made and used by the late Nik Rashiddin Nik Hussein.

PISAU WALI (CARVING KNIFE) (FL062)

Kelantan, late 20th c., kemuning wood, 17 x 4 x 3 cm

Langkasukan motifs finish this knife handle. Small pieces of kemuning that are not suitable for the carving of keris hilts are often used to make handles of this type. Motifs are designed to camouflage cracks or blemishes.

PISAU WALI (FL061)

Kelantan, late 20th c., kenaung wood, ivory, 16 x 3 x 2.5 cm

This is the last pisau wall made by Nik Rashiddin. The handle is formed of kenaung wood and the stupa finial from ivory.

It can thus be seen that the relationship between the woodcarver and the tree was a long and complex one that began with the process of identifying the trees he required for his work. By the end of the process, the woodcarver would have probably spent anything between five to ten years (in some cases, even more) with each particular tree, cultivating it, preparing it before it was cut down, carefully dissecting it piece by piece to find the best parts, preserving it, and finally putting it to use.

From Tree to Wood: Traditional Wood Care and Storage

Wood that had been cut from the forest was usually treated with great care and respect. The Malay woodcarver realized that the wood that was now in his possession was no ordinary material. It had come from a tree, which was a living thing endowed with semangat and nyawa, vitality and life, and thus had an identity and character of its own. In some parts of the Malay archipelago, respect for the living tree was so great that woodcarvers would perform specific rituals prior to felling the tree in the hope that they would be pardoned for their audacity in turning it into lumber.6

Woodcarvers in the past would also store their most prized pieces of wood in the rumah padi (rice storehouse), along with their supply of padi. This was a special privilege bestowed on particularly fine, and small, pieces of wood that were singled out to be carved into keris handles. The reason for this choice of location was simple enough: the rumah padi was thought to be particularly suitable because it had the right temperature and humidity levels. The air was never too damp, the ventilation was good, and the building was also free from vermin and other pests.

But there were other reasons as well, reasons that had more to do with the esoteric dimension of the semangat of wood. For it was thought that padi, being a life-giving and life-sustaining food source, was particularly endowed with strong semangat of its own. To maintain the semangat of wood, it was thought that the rumah padi was the best place to keep it, as it would ensure that the semangat of the wood remained at a high level. Thus, the connection between the semangat of wood and the semangat of padi was a strong one. (It is important to note that in the past, other items and objects of strong semangat were stored in the rumah padi as well. This included the blades of keris, spears and other weapons or ritual objects.

Having stored the wood in the rumah padi, the woodcarver would leave it there to dry for several years. Some woodcarvers have been known to keep the wood in their rumah padi for dozens of years, until it had reached the required levels of dryness and hardness that gave it the strength and resilience that the woodcarver desired. During this prolonged period, the store of padi would be changed and replenished time and again, while the wood in the rumah padi would merely accumulate the semangat that was being stored in the same place.

A pisau wall handle. Drawing by Norhaiza Noordin.

Foliate spirals commonly used on keris tajong hilts and on architectural elements. This particular example appears on a post at Masjid Pulau Condong, Kelantan. Drawing by Norhaiza Noordin.

A keris hilt decorated with the leaves of the ketumbit, a common garden herb. Drawing by Norhaiza Noordin.

Larger pieces of wood would be kept under the house of the carver himself, which was raised on posts above the ground. Before storing, woodcarvers often cut these pieces into lengths of about two feet (60 cm). These would then be left under the house, often for years, allowing them to age naturally and to dry out. It was important to store them in a place where they would not be exposed to direct sunlight as this could damage the grain of the wood.

While the wood was being stored in this way, it was also important that it should not be moved for any reason. Traditional woodcarvers believed that while the wood was being dried, its orientation should not be altered. If this were to happen, they believed that the colour and grain (pela and coreng) of the wood might be adversely affected and might change dramatically. The woodcarver would therefore check his wood periodically, observing it for the smallest changes that would indicate to him when a particular piece was mature enough for use.

Another curious way of keeping wood for future use was to utilize wood that had been used for other purposes elsewhere. It must be noted that this practice cannot and should not be compared to modern modes of recycling, for the wood in this case had not been simply discarded or deemed unfit for use. What the woodcarvers were doing was simply working on wood that was already in everyday service around them. An example of such a practice can be found in the way that some woodcarvers used wood that had come from parts of their houses, such as the beams or the foundations. Having decided that a particular section of the wood was mature enough, the woodcarver would simply remove that piece and replace it with a newer piece. The wood that was removed was then cleaned, cut and treated before it was put to other uses such as keris handles or sculpture. (Some present-day woodcarvers continue this practice of obtaining wood from old houses and palaces that have been dismantled or have simply been left to deteriorate.)

Once again, there are both simple and complex explanations for the process of using old wood. On the simpler level, one could explain this as a straightforward process of replacing wood and utilizing material that had been already put to use and was thus tried and tested. But the esoteric dimension of the process provides us with a more complex explanation. Traditional woodcarvers justified the practice on the grounds that it was a good way to prepare wood that would be endowed with strong semangat. Having already put it to use in a human habitat, such wood would have 'fed' on the life forces or semangat that was surrounded it and grown even more potent over the years. To put it simply, such wood had become 'accustomed' to human beings and was thus better able to 'serve' them.

The storage of wood was therefore not a simple process for the Malay wood carver. He was not merely keeping the wood aside for future use, but was preparing the wood for higher ends. Prior to working with the wood, the woodcarver was slowly growing accustomed to it and trying to uncover its hidden mysteries. The Malays learnt that in order to have a proper relationship with wood, they had to first discover its secrets.

Knowledge of semangat was thus critical for the proper use and work of wood, and one could only bring out the best of any kind of wood if one possessed the appropriate knowledge of its particular semangat. Higher woods were—and still are—used for higher, nobler ends, while lesser woods were reserved for common usage. This then is the adab (custom) of wood and woodcarving.

HILT, KERIS TAJONG (KW014)

Pattani, pre-18th c., kemuning wood, 6.6 x 11.1 x 3.6 cm

Close-up of a very early keris tajong hilt from Pattani (see pages 118-19).

From Wood to Art: The Adab of Woodcarving

Classical Malay woodcarving was never an industry. It was a vocation with a credo and adab all of its own, and rules that were then known only to a select few.

The preparation of the wood itself was half the task. As we have seen, the wood-carver would spend years preparing the wood that he was going to work with in order that there would be a perfect match (jodoh) between himself and his material. Traditional woodcarvers believed that they could produce their best work only if they were working with wood that was compatible (serasi) with their own personalities. When making pieces that were intended for the personal use of others, such as keris hilts, the woodcarver also had to ensure that the wood he chose was compatible with the person the object was intended for, thereby complicating his task even further. This kind of intimate knowledge was known as ilmu falak. It was only when these conditions had been met, that the woodcarver could even contemplate the task that lay before him.

Prior to embarking on a carving, the Malay woodcarver would first carry out several rites and rituals of preparation. He would wake up early in the morning, before dawn, and begin his day with devotional prayers. His body had to be cleansed in every respect, because no traces of pollutants or contaminants were permitted. He had to purify himself, not only physically but also mentally and emotionally.