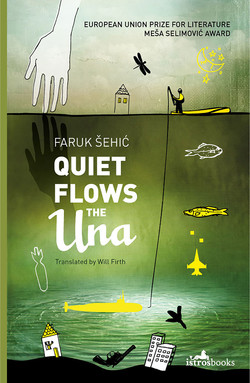

Читать книгу Quiet Flows the Una - Faruk Šehić - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCatching a Fish

‘The Bulgie!’

That shout had an almost shamanic weight to it. ‘The Bulgie’ was an old woman who lived in a run-down Austro-Hungarian villa on the very bank of the Unadžik, where the river had made a particularly deep greenhole, and then flowed frothing through a narrow, stony channel beneath a wooden bridge and the old abattoir. The Bulgie lived alone in that big house, whose façade was crumbling due to the damp. There were orchards with long, swaying grass around her house, and we used to run through them, tearing bedewed cobwebs in our search for ripe apples. The old woman’s nickname came from her late husband, who was allegedly Bulgarian, and the opaque greenhole just a few metres from her house was also known by that nickname.

‘Bulgie’s greenhole’ was home to pike, chub, grayling, barbel, troutlet and adult trout. Willow branches on the opposite bank leaned over the water and lightly caressed the surface. Very large trout lurked there and would launch out at floating flies. The pikes were to be found closer to our bank, where they waited for the swarms of young fish. The bottom was sandy and silty from decayed leaves and wood. If you waded out into the silt, columns of air bubbles and the black ink of fossilized wood rose towards the surface. And everywhere there were calf’s skulls, shoulder blades and other bones that the butchers dumped into the river from the wooden bridge. Inside the skulls that had almost become part of the tufa we used to find fat yellow maggots. They hid in cases made of sand and fragments of wood. First you take the maggot by the feelers on its brown head and pull it out of its case. When you take it out, it writhes like a new-born baby, and tries to wriggle out of your hand. We would put them in yoghurt containers or jars filled with water so they would stay fresh and alive. Then they were hooked, usually through the head, because if the maggot’s body was punctured it oozed an ichor and puffed up like balloon. The yellow maggots were worth their weight in gold to anglers, and only passionate connoisseurs of the river knew where to find them. That maggot was the larva in the life cycle of an insect from the order of caddisflies (Lat. Trichoptera). We also called them ‘water blossoms’ or ephemeral mayflies because when they turned into winged adults after a year or two as larvae underwater, struggled free and made their hazardous way to the surface, they only lived for one more day.

Once my friend Sead and I caught an enormous pike near the Bulgie’s. We cast and cast for hours, skilfully drawing metal lures through the water. It took Sead’s spoon lure, and after a short fight he pulled a two-kilogram pike up onto the sandy bank, where I was hopping about with joy. How exciting is it when you see a fish open its white jaws and take the bait. The creature flashes in the water and turns its silver belly towards the surface. Afterwards it tries to get the lure out of its mouth by vigorously shaking its head from side to side, beautiful in its bewilderment. The rod bends from its weight like the letter omega. As I was trying to remove the three-headed hook from the pike’s lower jaw, it bit me and bloodied the back of my hand. The pike’s head was twice the size of my fist. Frightened and in pain, I hit it several times on the head, which was stupid because a pike’s gill covers are sharp too. We returned home at dusk with the big fish, happy despite the fact that I was bloody, wet and hungry. The moon shone through the branches above the river, blessing the richness and crystal clarity of the water. The whirr of ducks’ wings furrowed the air full of the river’s aromas. I had to go to sleep and wait for daybreak, and in the morning I would immediately spread the story of my amazing catch in the greenhole near the Bulgie’s.