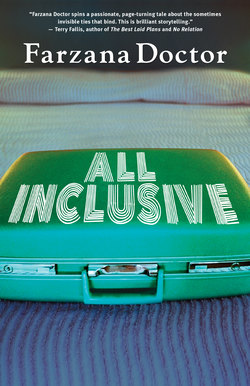

Читать книгу All Inclusive - Farzana Doctor - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Ameera

Оглавление∆

“We are going to go pack our bags now. We leave tomorrow morning,” Serena said, with a wan smile. There was a purpling smudge on her neck, a mark I’d left behind.

“Have a good trip home, you two.” I smiled politely and glanced at Manuela, who was flipping through a newspaper, likely eavesdropping.

Serena’s long white tunic fell an inch below her knees, as ungainly as a paper bag. Sebastiano’s Bermuda shorts and loose polo shirt cloaked his muscular frame, making him resemble any other middle-aged tourist. I realized, with a catch of disappointment in my stomach, that they weren’t going to ask me out again. I imagined the late morning debrief that would have determined this. Had they evaluated my performance over coffee? Whose opinion would have held more sway? Never mind, I’d scope the bar again on Thursday.

“I wish we didn’t have to leave this paradise.” Sebastiano affected a sad-sack expression, his lower lip pushed out. I had an urge to taste the soft meat of it.

“Good luck with your search for your father.” Serena said this with the kindness of a kindergarten teacher. I stiffened as the pair turned to walk away.

Frowning in concentration, I scrambled to recall the previous night’s conversation. We’ d all spoken casually about our families early in the evening, when we were making idle chatter about our lives. But what had I disclosed after the fourth drink? I wanted to jump up and follow them to find out what I’d forgotten, but my thighs were stuck to my stool’s vinyl seat.

“You’ve never talked about your father before.”

I looked off in the direction of the disappearing Italians, prickling under Manuela’s curious stare. She apprised me of her family’s news on a daily basis. Just that morning I’d learned that she’ d mediated her sisters’ bickering about the youngest’s quinceañera party.

“Oh, yeah. I don’t know anything about him.” I shrugged, as though speaking about him didn’t always cause a lump to form in my throat. I took a sip from my diet cola to push it down. Why would I have told Serena and Sebastiano about him?

“I always thought he’ d died or something.”

“My mother lost touch with him before I was born. I’ve been thinking about looking for him. Maybe. I dunno.” These words, spoken aloud, sounded surreal. I had imagined a serious search for him numerous times over the years, but the idea hadn’t progressed beyond an uneasy notion.

“Any idea where he might be?”

“India. Probably.” I sucked down the last of my drink, aspirating through ice. “That’s where he’s from. But he could be anywhere.”

“I wonder if you look like him. I don’t think you look like your mother at all.” Manuela said. She’ d met her twice when Mom came to Huatulco on vacation.

“Mom says so, but she doesn’t remember a lot of details. She only knew him for one day.” I looked at my hand, the one part of me that matched my mother. We both had long, thin fingers, the middle one standing noticeably taller than the rest. A small birthmark squatted in the middle of each of our heart lines, a sign of good luck at midlife, according to a palm reader we’ d once visited at the Ancaster Fair. As a child, I liked to press our matching hands together.

“One day?”

“Yeah.”

“Wow,” Manuela said. I doubted Manuela had ever had a one-night stand, or if she had, she’ d never said so. She very much desired matrimony and motherhood. Three kids, preferably two girls and one boy, in that order, and she had chosen names. Although she’ d accepted a promise ring from a previous suitor, none of the men she’ d dated in recent years had turned out to be a potential husband. I’d long suspected that Manuela had a crush on Oscar, but when I once teased her about him, she vehemently denied it.

“Hey, we should go. It’s quitting time.” I looked at my watch.

We collected our things, and repacked and folded the tour desk until it once again resembled a locked rectangular box. We headed off in opposite directions, Manuela to the lobby, where a golf cart would shuttle her to the main road, and I toward the staff dining room.

I filled my dinner plate with rice, refried beans, and cooked vegetables. I avoided the mini-sausages, buns, and crudités, anything that might have been previously picked over by dirty hands. A large slice of angel food cake beckoned and I added it to my plate. It was just after six, early for most of the workers to eat dinner, and I easily found an empty table in a windowless corner. I stared at a painting across from me of a calm acrylic sea reflecting an orange sunset.

I shovelled in the bean and rice slop, its mushiness pleasant against the roof of my mouth. The lump in my throat made way and I swallowed it down with the food. I consumed the cake in three greedy swallows.

∆

Having an unknown father marked me as different, even more different than I already felt as a light-brown-skinned daughter of a white single mother in a town where it seemed no one had a family like ours. Mom didn’t like talking about him. I think it exposed her as someone she didn’t want to be: the sort of girl who got pregnant with a visa student she’ d known for only a single afternoon; the sort of girl who was sloppy about taking her birth-control pill; the sort of girl who had to turn her back on ambitious academic plans to raise a child.

When she did speak about him, her stories were designed to help me avoid the same choices she’ d made. The more detailed the story, the more serious the warning. Some were told and retold, with each recounting further embellished to properly highlight the specific lesson to be absorbed.

The night of my prom, Mom confessed that she’ d met my biological father a few days after she’ d been dumped by the boyfriend she’ d been with all through university, a guy she’ d expected to marry. Their ending was abrupt and humiliating and he’ d begun dating someone else a few days later. So, when this exotic-looking guy showed interest in her, she impulsively asked him back to her place.

My heart was broken, and he seemed kind.

This was her lesson about rebounding.

She also admitted that she’ d been too shy to talk about condoms with him.

Prophylactics, she’ d called them. I’d laughed nervously and Mom shushed me, urging me to pay attention.

I should have told him to wear one. I hadn’t been consistent with the pill since the breakup..

She followed this admission with rushed reassurances about how glad she was that I had been born. About how if she could go back in time, she wouldn’t change a thing, that life is a gift and other such clichés. And then she warned me to never trust a man with my body.

Don’t believe it when they say they’ll pull out.

I felt squirmy, like a dozen spiders crawling up my back. I didn’t want to picture her under a panting man.

And you can never be too safe these days with AIDS and chlamydia and warts. Trust me.

Later, I stood at the school’s bathroom mirrors, Usher’s “You Make Me Wanna” wafting in from the gym. Rifling through my purse for lipgloss, my fingers brushed against a ticker-tape length of multi-coloured condoms. I showed my friends the rainbow rubber disks, and they laughed at Mom’s stealth. They misinterpreted her deepest fear as her being a progressive mom. I distributed them, tucking a purple condom into my wallet, imagining it might taste like grape.

For years I wanted a better story. Perhaps if he was dead, even. A car accident, a tragic illness, a random shooting all would have been fine. I pined for a narrative that would provide closure and elicit sympathy, while leaving me intact, a child who was planned for, loved, even if I was still left. But Mom didn’t know basic details like his exact height, what subject his PhD was in, or the name of his hometown. I wanted more. Needed more. What I had instead was an absence, a mystery, a relationship that never existed.

My ideas changed when I met Malika and other university friends who were brown girls with white mothers. Being different was no longer the same sort of problem as when I was a kid. Turned out, it was kind of cool. I finally had an identity that I could say in one sentence: I was the mixed-race daughter of a strong single mother. Period. I could almost forget that I didn’t know my biological father’s surname. Almost.

Mom caught me off guard when she raised the question of searching for him. I was in fourth year, nearing graduation. The same age she was when she met him.

“Have you ever wanted to know more about him?” She pulled out a tube of lip balm and ran it around and around until there was a thick, globby layer coating her mouth.

“I don’t know. I don’t need him. He’s a stranger, right?” I gazed at her, gauging her reaction. She exhaled and applied another layer of lip balm.

“Well, you never know,” she said hesitantly, as though she didn’t want to believe her own words, “you might change your mind one day.”

“I don’t think so, Mom. You’ve done a great job being a mom and a dad.” While my reassuring words were true, I just wasn’t ready to risk my durable identity turning flimsy again.

∆

I helped myself to a glass of milk. Then I cut myself a second slice of cake and carried both to my table. This time I ate slowly, wanting to extend my mealtime.

The murmurings of wait staff and employees arriving for their dinner felt like company. The cafeteria filled in around me, and a group of gardeners claimed the table next to mine. Ruben, the nice older man who mowed the grass in front of my building, beckoned me to join them. Did I look sad, sitting there all alone? I waved back, gesturing that I was finished eating, then left the cafeteria.