Читать книгу Back to the Postindustrial Future - Felix Ringel - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Knowledge and Time/Knowledge in Time

ОглавлениеThere is no need to be in awe of time, which is no more mysterious than any other facet of our experience of the world.

—A. Gell, The Anthropology of Time

In the eyes of many Germans, Hoyerswerda is just another East German city with ‘no future’. A former avant-garde settlement where the socialist future was daily facilitated, Hoyerswerda faces social decline more strongly than other postsocialist cities, a continuously decreasing and ageing population, and unrestrained physical deconstruction. It has lost its economic foundation and with it its modernist raison d’être. By all accounts, Hoyerswerda is perceived as a hopeless case. Still, as shown in the previous sections, the city remains infused with an urge towards the future. However, the new temporal framework of shrinkage fundamentally questions any future prospects for Hoyerswerda. It outruns in bleakness the disillusioning loss of the hopes of the postsocialist transition. As shown above, in the process of shrinkage, uncertainty prevails not only in the domains of urban planning, the housing market, the education system and other public domains, but also in personal lives. People have lost the security they needed to plan the future. They cannot be sure that their jobs, schools, dentists, favourite restaurants or football clubs will continue to exist in the years to come.

The commonly expected responses to problems with the future – nostalgic attachment to the (in this case socialist) past8 or Guyer’s otherwise accurate enforced presentism/fantasy futurism-dyad – set strong limits to the capacity of Hoyerswerda’s inhabitants to discern not only change and a different future, but to the ability to envision a future altogether. They also do not provide convincing reasons for the fact that people nonetheless continue in myriad ways to direct their practices and lives to the future (see Crapanzano 2007). What kind of ethnographic object and analytical tool are hope and knowledge of the future? And how should we approach temporal agency in this context of shrinkage?

My ethnographic material consists of the local mediation of Hoyerswerda’s present and future by its citizens. As Donna Haraway (1988) pointed out, knowledge is always situated; this means it is part of a specific social context and manifests there as the interface of sociopolitical processes of negotiation (Boyer 2005) and personal interpretations of the world (Barth 2002). In a presentist framework, I account for both the ‘radical historical contingency for all knowledge claims and knowledge subjects’ and the ‘radical multiplicity of local knowledges’ (Haraway 1988: 579). Accordingly, I approach knowledge less as an access point to local cultures (something ontologically given) and more as radically contingent, collectively negotiated outcomes of a multiplicity of local knowledge practices. In Hoyerswerda, as elsewhere, these negotiations happen in discourses among friends and family members, at all sorts of social gatherings, professional city planning procedures, in expert circles, around conference and coffee tables, at public speeches and sociocultural projects targeting the city’s future. This book maps a variety of public engagements with the city, presenting a citizenry that passionately produces and discusses knowledge about its own life, city and future.

Such a practice-based approach to time and knowledge (see Rabinow 1986) throws light on local politics and the way in which the future is made to play a role in Hoyerswerda’s citizens’ lives and experiences. It has a longstanding tradition in the discipline of anthropology. As Gell in The Anthropology of Time pointed out, Durkheim in his The Elementary Forms of Religious Life already made clear ‘that collective representations of time do not passively reflect time, but actually create time as a phenomenon apprehended by sentient human beings’ (Gell 1992: 4). However, I concur with Gell’s critique of Durkheim, whose ‘thesis of the social origination of human temporal experience offers the prospect of a limitless variety of vicarious experiences of unfamiliar, exotic, temporal worlds’ and ‘their distinctive temporalities’ (both ibid.). In contrast to such an ontologizing idea of temporality as a homogeneous, closed cultural system (compare Ringel 2016b), and in accordance with Gell, I define time as an issue of (knowledge) practices, politics and changing social conventions, but not as an aspect of culture, a term that, for example, one of the most influential theorist of knowledge, Michel Foucault, in his early works uses only very unreflectively (for example, Foucault 2004 [1961], 2005 [1966]).

As Gell emphasizes, instead of searching for distinct temporal cultures, we should instead account for a more specific ‘contextual sensitivity of knowledge’ – including temporal knowledge: ‘how much a person “knows” about the world depends not only on what he has internalized and what … is in his permanent possession, but also on the context within which this knowledge is to be elicited, and by what means’ (1992: 109), that is, the present context of its production. For example, as he observed in Bourdieu’s early work, the Kabyle ‘operate with a multitude of different kinds of temporal schemes, appropriate to specific contexts of discourse or action’ (Gell 1992: 296). In Hoyerswerda, I am going to discern different forms of reasoning in similar ways. In both cases, political claims to time are part of the ‘continuous production of socially useful knowledge’ (ibid.: 304). Gell very successfully poses this idea of ‘contingent beliefs’ against ‘the doctrine of temporal “mentalities” or “world-views”’ (ibid.: 55).9

Carol Greenhouse also emphasizes the politics of time, and reminds us that we have to think about time and temporal representations always in relation to, in her case, changing or contested conceptions of social order and agency (1996: 4). As in Gell’s analysis, this goes beyond wondering about the ‘geometry of time’ (ibid.: 5), that is, its presumed cyclicity or linearity. Whereas she still focuses on temporality as an aspect of culture, I concentrate on the particular knowledge practices that reference different temporal dimensions. As she observes, however, any dominant formulation of temporality is, in fact, hard to be maintained (see ibid.: 82). Following Greenhouse, we could define shrinkage as the dominant formulation of time in Hoyerswerda, and it comes with the dominance of a particular version of temporal reasoning, what I call ‘enforced futurism’ – a constant attention to and problematization of the temporal dimension of the future. This form of temporal reasoning might have its histories (compare Rosenberg and Harding 2005; Pels 2016) or buy into particularly long-lasting problematizations (Rabinow 2003: 56), but I claim that there is no historical force that determines these practices. From a presentist point of view, the agency expressed in them might yield surprising results against all odds. Indeed, relations to the future in postindustrial modernity require the production of specific kinds of knowledges. As Ferguson has pointed out, these different kinds follow ‘the need to come to terms with a social world that can no longer be grasped in terms of the old script’ (Ferguson 1999: 252), in which dominant temporal frames fail to convincingly deliver epistemic clarification.

Ferguson claims that we should focus on the epistemic consequences of such changes. In Expectations of Modernity, he advances an ethnography of decline in which he strongly argues against modernist linear narratives, whilst emphasizing our discipline’s own investments in these temporal knowledge regimes. He contrasts their counterparts (deindustrialization, deurbanization and de-Zambianization) to his informants’ various expressions of agency. His aim is to trace the decline’s ‘effects on people’s modes of conduct and ways of understanding their lives’ (ibid.: 11–12). Whereas he sees most hope for overcoming the decline in the past as a resource for countering the false future promises of the modernization narrative, I want to establish the future as a resource for countering narratives of decline and shrinkage.

Facing widespread problems of and with knowledge itself, how do we specifically approach knowledge about the future? As I have pointed out above, I investigate particular forms of temporal thought, practice, affect, ethics and agency in a context where the future is rendered problematic. In short, the future is not just a matter of professional planning practices in local, regional and national state institutions or their citizen’s responses. Rather, the future is created, related to and represented in a variety of different arenas, such as art, social, cultural and other communal milieus, and many more places. Accordingly, through their practices, many inhabitants of this shrinking city have become new experts of the (postindustrial) future.

However, if we follow the German philosopher Ernst Bloch’s central predicament of The Principle of Hope (1986 [1959]), namely, that men are essentially determined by the future, we have to acknowledge that most social sciences still lack a comprehensive methodological and analytic toolkit for accounting for the future and the role it plays in human life. Liisa Malkki describes this as the ‘theoretical invisibility of the future’10 (2000: 326). Akin to my approach, she concludes that ‘futures as well as traditions and histories are constituted in and constitutive of present struggles, identities … communities, and social formations’ (ibid.: 28–29). The acknowledged abundance of relations to the future – ‘Once we start looking, it becomes clear that much of our political energy and cultural imagination is expended in personal and collective efforts to direct and shape (and, sometimes, to see) the future’ (ibid.) – provides enough ethnographic material to the future as an important matter of knowledge, particular in contexts of crisis such as Hoyerswerda. Surprisingly, for Malkki’s informants (Hutu refugees in Canada), it is not the past that is problematic, but the future. However, as Bamby Schieffelin pointed out, since the ‘future is the most unknown of the temporal dimensions’, it ‘has to be marked in the present’ (Schieffelin 2002: 12). As a result, we can access the future’s ‘existence’ in the present through the knowledge, which is produced and reproduced about it in the present.

In modernity proper, as Rabinow claims in his discussion of the German sociologist Niklas Luhmann, the future has been configured as a problem: it ‘appears as a contingent set of possibilities about which decisions are demanded; decisions are demanded because the future appears as something about which we must do something’ (Rabinow et al. 2008: 57). In times of postindustrial shrinkage, this seems as impossible as the undisturbed production of other narrative trajectories. Rather, the change of the content and form of particular (temporal) knowledge practices also accounts for the ways in which human beings position themselves and their agency vis-à-vis the changes they are experiencing. The trope of shrinkage, like other epistemic tools, provides a very distinct imagination of the future and yields specific epistemic repercussions. This book tries to locate, map and conceptualize agency in this context of shrinkage (see Ringel 2016a, 2016b). The methodological question – less about how to study time and more about how to study knowledge (about time) and the temporal dimensions of knowledge – translates into a focus on what Morten Nielsen (2011) calls ‘anticipatory actions’, which for him are guided by both unknown and known futures, and that help to reorient individual life trajectories by exploiting the former’s imaginative potentials.

However, ‘unknown futures’ are not ‘no future’. As a city with ‘no future’, Hoyerswerda could, indeed, be seen as one of the places where the unequal distribution of hope (Miyazaki 2010) drew away the prospects of a better future. Deploying Miyazaki’s own work (2004), this entails the loss of hope’s epistemic function: with no hope, people lose the ability to (radically) redirect their knowledge. However, as Zigon (2009) argues, this urge for a radical redirection of thought is not necessarily hope’s main point. Rather, hope entails particular incitements to maintaining practices – conceptually, ethically, and relationally (Ringel 2014). Apart from the need to diversify analytical approaches to the future, there is still an issue with the logic, practicality and efficacy of representations of the future in the present, which also needs to be taken into consideration. However, as I claim, this will only ever allow new insights into the present in which this knowledge is produced. As Miyazaki, for example, underlines in a different context, once the future is feared or otherwise made concrete, the present is itself imagined ‘from the perspective of the end’ (Miyazaki 2006: 157; compare Miyazaki and Riles 2005). However, ‘the end’ in my informants’ temporal knowledge practices is much more indeterminate than Miyazaki suggests. In the context of shrinkage, the challenge is to have an accurate idea of the future in the first place. As I will show in the following chapters, under this paradigm, Hoyerswerda’s citizenry continuously establishes arenas for the common imagination of the future whilst struggling daily with the imposition of official dystopian demographic, economic and social visions of the city’s future. This hopeful reappropriation of the future has been described by Appadurai (2002, 2013) as a political right, a right to aspire and to participate in the social practice of the imagination.

Finally, any consideration of our informants’ hope and future knowledge should also involve what is at stake with regards to the hopes and futures of the ethnographer and analyst. Most of the aforementioned scholars attach a particular form of hope to including the temporal dimension of the future in their analysis. As Ernst Bloch has it, only ‘philosophy that is open to the future entails a commitment to changing the world’ (quoted in Miyazaki 2004: 14). Miyazaki remains cautious with regard to the ‘ongoing effort in social theory to reclaim the category of hope’ in a broader ‘search for alternatives’ in times of the ‘apparent decline of progressive politics’ (ibid.: 1–2). The hopeful moments sustained in his fieldsite’s many knowledge practices show one efficacy of hope to be a method for the production of future knowledge: the continuation of thought (and) practice against all odds. Methodologically, Miyazaki answers his own questions of ‘how to approach the infinitely elusive quality of any present moment’ (ibid.: 11) by looking at concrete knowledge practices over time whilst being aware of their indeterminacy. In a presentist vein, he thus resolves the mundane paradox ‘to cherish indeterminacy and at the same time expect it to be resolved’ by showing how that ‘requires constant deferral of … closure for the better’ (ibid.: 69). For him, the maintenance of hope, despite its constant failure, affects not only our informants’ lives, but also our own academic practices. In Hoyerswerda, a city with supposedly no hope and no future, the analysis of questions of knowledge and the future require a similar continuous reflection upon my own hopes and relations to the future. This also allows for a different methodology.

Once we conceptualize issues of time to be matters of representation and understand that the production of knowledge about the future in a dramatically changing fieldsite keeps on changing too, anthropological representations of these practices remain necessarily inapt. All they can do is become part of this process by joining the search for more sustainable or convincing takes on the future. This methodological move is based upon an understanding that my informants are recursively adjusting their social metaphysics in order to find contexts and narratives for describing their current and past experiences. They do so collectively, passionately as much as pragmatically and in conflict with one another. As I claim in more detail elsewhere (Ringel 2013b), this continuous epistemic work allowed for several different forms of intervention during fieldwork. I therefore published weekly newspaper columns in the local newspaper over the course of a whole year, conducted a week-long anthropological research camp for sixteen local youths and initiated a two-week community art project.11 However, the instability of local representations, particular with regard to the future, also prevents me now in the process of writing from authoritatively imposing my own conclusive representation upon this local processual heterogeneity.

To sum up this section, the analysis of time has long focused on particular and situated social practices. The undoubtedly interesting theoretical concerns regarding the distinction between linear and cyclical time have been dissolved in a general trend to de-ontologize human understandings of time. In contrast, with attention being paid to the local construction of temporal knowledge – that is, knowledge about time and knowledge that reaches out in time – recent anthropology acknowledges that the flexibility and multiplicity of forms of temporal reasoning challenges notions of temporal knowledge as culture or given temporalities (Ringel 2016b). With a strictly ethnographic approach, anthropologists could subsequently show how this particular kind of knowledge is infused with political and ethical relevance, since it is deployed for fundamental claims on both the past and the future in the present, and on life and what it means to be human. The future in particular thereby gains a newly prominent standing in anthropological analyses. Representational and nonrepresentational dimensions of human relations to the future allow insights into the efficacy of knowledge about the future as much as the wide-ranging registers that are deployed in many different forms of practices to relate to the future. In this book I map a variety of local temporal knowledge practices and their relation to the future in order to continue this theoretical quest. To rephrase Gell slightly, there is, indeed, no need to be in awe of the future.

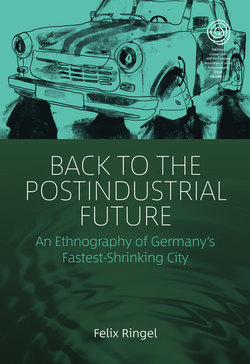

Figure 0.3 Anarchist graffito, KuFa building, Hoyerswerda, men’s toilet, 2009, ‘Utopias to Reality; Shit to Gold!!!’