Читать книгу Fidel & Religion - Fidel Castro - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление20 YEARS LATER

INTRODUCTION TO THE NEW EDITION

FREI BETTO

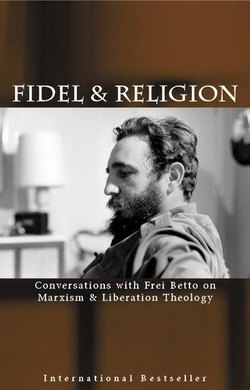

It is amazing that 20 years after the launching of the Spanish edition of Fidel and Religion in November 1985 it should remain so timely. The lead up to this book involved a series of unexpected events and coincidences. It had never occurred to me that I would have the privilege of listening to the comandante [Fidel Castro] in a long interview, though I had begun my professional career as a journalist — an activity in which I am still involved, as it is entirely compatible with my pastoral work as a Dominican friar.

I was very grateful when, after a conversation in Havana in February 1985 that lasted from 11 p.m. to 7 a.m., Fidel agreed to give me a brief interview. The Cuban leader usually works at night, and in addition to being an excellent speaker, participates in discussions with tremendous enthusiasm. He never meets with an interviewer for just 10 or 15 minutes. Generally, he spends hours talking — preferably, those just before dawn — because he’s interested in hearing everything his visitor has to say. With a mind open to all topics, he asked me for details about the cooking in the monasteries, the friars’ library, the system of studies and methods of preaching the gospel. Or he would ask about the economy, climate, political forces and history of the visitor’s country. He also took the opportunity to talk about the Cuban revolution — its achievements, mistakes, limitations, and advances — never falling into leftist clichés or quoting the Marxist classics.

At that time, I wanted to write a small book about Cuba, including my interview with Fidel as an epilogue. I had been told that the comandante didn’t give many interviews (he receives hundreds of requests for interviews every month) and that, in particular, he didn’t like to talk about his private life. Even so, something caught my attention in our talk that early morning in the home of Chomi Miyar, his private secretary: Fidel recalled his Catholic training — both in his family and at the La Salle Brothers’ and Marist Brothers’ schools — with enthusiasm and a touch of nostalgia. I, too, had studied at a Marist Brothers’ school. Would he be willing to repeat what he’d said in the conversation during an interview? He said he would and suggested that I return to Cuba three months later.

SECULAR GOVERNMENTS AND PARTIES

At first, I was drawn to Cuba for ideological reasons. I was 14 at the time of the triumph of the revolution. One year earlier, I had begun to take part in leftist student politics. Our opposition to the United States was affirmed when the bearded fighters from the Sierra Maestra mountains entered Havana in triumph.

Then came the war in Vietnam and the military dictatorship in Brazil (1964–85), which was sponsored by the CIA. A victim of state repression, I was arrested and spent two weeks in prison in 1964 and another four years in prison starting in 1969, thanks to my student militancy and to my support for those whom the dictatorship persecuted for political reasons. Those experiences increased my sympathy for the Cuban people’s heroic resistance and my opposition to US policy in Latin America.

During the military dictatorship, Brazilians weren’t allowed to talk about Cuba. I remember that one time when I was in prison, I was sent a collection of books. On checking the list, I saw that one was missing: Cubism. When I asked for it, I was told that the prison’s censor had sent it back to my family, because I wasn’t allowed to have works about Cuba…

In 1979, the presence of Christians in the Sandinista revolution led me to visit Nicaragua. There, at writer and Vice-President Sergio Ramírez’s home, Lula — now president of Brazil — and I met Fidel Castro on July 19, 1980. We spent the whole night talking, and I saw that the comandante was surprised to hear me speak of liberation theology. I asked him why the Cuban government and Communist Party were confessional, and he reacted strongly to the description: “What do you mean, ‘confessional’?” I replied, “They are confessional because atheists are officially recognized. The confessional character of an institution is based not only on affirming the existence of God, but also on denying it. The secular nature of governments and political parties is one of the achievements of modern times.”

After the launching of the Spanish edition of Fidel and Religion, the Cuban government modified the constitution, and the communist leaders changed the party statutes, making them secular, which opened the doors of the Cuban Communist Party to those who professed religious faith. I asked Dr. Carneado, who was in charge of relations between the Cuban government and the religious denominations at the time, if the opening had brought many Christians into the party. He told me that the most surprising result was the discovery that many members of the Communist Party had retained their faith — now, they were able to admit it publicly without running the risk of being excluded from the ranks of the party.

FRICTION BETWEEN THE STATE AND CHURCH

In 1981, Fidel invited me to advise the Cuban government in its rapprochement with the Catholic church. Strongly influenced by Spanish Catholicism — the religious branch of General Franco’s dictatorship — the Catholic church in Cuba in those pre-Vatican II days wasn’t able to see the revolution in an unbiased way. As a result, it let itself be manipulated by the US government, which opposed the new Cuban regime when it realized that, after overthrowing the dictator Fulgencio Batista, the revolutionaries weren’t going to impose a class dictatorship by the country’s elite under the cloak of democracy. The time had come to respect the rights of the poor, which meant a literacy campaign, agrarian reform, urban reform, the confiscation of foreign-owned property, an end to the casinos and to prostitution, and national sovereignty.

It was the United States that thrust Cuba into the arms of the Soviet Union. It should be recalled that, immediately after the victory in the Sierra Maestra mountains, Fidel drove through the streets of New York in an open car. After the unsuccessful US landing at the Bay of Pigs in 1961 — the mercenaries sent by Kennedy included three priests — Cuba had no alternative for defending itself than to ally itself with the other geopolitical pole that existed in the world at that time. The adoption of socialism led to the breaking of relations between the state and the Catholic church, but there was no persecution and no churches were closed. The church didn’t believe that the revolution could become so deeply rooted among the people. Angered by the confiscation of its property and by the secularization of its schools, it took an anticommunist position of trying to restore “freedom” and “democracy.” Clashes were inevitable. In spite of everything, the revolution continued to respect religious freedom, and good relations were even sought with the Vatican. However, the identification of the Catholic clergy with counterrevolutionaries and the ideological rigor of a party that was officially atheist caused tension and made dialogue difficult.

CUBAN RELIGIOUSNESS

The Cuban people are deeply religious. Cuba is not an exception in Latin America, where the primary ideology of an ordinary person is expressed in religious terms. The main historic figures in Cuba — Father Félix Varela and the poet and revolutionary José Martí — were outstanding for their deep-rooted spiritual and Christian convictions. A Catholic priest — Guillermo Sardiñas — took part in the guerrilla war in the Sierra Maestra mountains and rose to the rank of commander of the revolution.

Santería — an Afro-Christian syncretism similar to that in Brazil, resulting from the fusion of Iberian Catholicism and the animism which the slaves brought from Africa — is widespread in Cuba. Classifying Santería as “folklore,” the revolution learned to coexist with it. It also achieved positive relations with the Protestant churches, in spite of their US roots.

The Catholic church never put down deep roots in Cuba. Prior to the revolution, it was the religious denomination of the elite and of the middle class — of those who could pay for their children to be educated in Catholic schools. As Fidel noted in the interview, this could be seen in the large number of Catholic churches in the cities and the almost complete lack of them in the suburbs and countryside. However, the revolution never ignored the Catholic church’s weight as an institution. The church has great symbolic authority, and its international relations, established by the pope, are important both politically and diplomatically. This was why Fidel wanted to maintain good relations with the Catholic community.

RESISTANCE OVERCOME

In 1981, with the consent of the Cuban bishops, I began working to promote a rapprochement between the state and the Catholic church in Cuba. Its highest expression turned out to be the publication of this book. I returned to Havana in May 1985, prepared for the short interview that Fidel had promised me in February, but the situation had changed. In Miami, the counterrevolutionary community had inaugurated Radio Martí, which directed its transmissions at the island. Fidel didn’t want to give the interview. He was too busy with this new “virtual” attack on the revolution.

I remembered Hemingway’s masterpiece The Old Man and the Sea, which describes an old fisherman’s efforts to catch an enormous fish. Fidel was the big fish I had to catch. It was now or never. Some opportunities never come twice. I insisted that he keep the promise he’d made in February. Fidel resisted and resisted, but finally said, “What questions are you going to ask?” I’d made a list of more than 60 and started reading them to him. When I got to the fifth one, he interrupted: “We’ll begin tomorrow.”

What made Fidel agree? I’m convinced that it was the content of the questions. My questions weren’t theoretical: no speculations about Marxism and religion. Nothing about Feuerbach or Lenin. My questions were friendly. I was interested in the key family, educational, and political events in Fidel’s life. How had that son of a Catholic land-owning family who had been educated in Catholic boarding schools for 10 years become a communist leader? (After the triumph of the revolution in the Sierra Maestra mountains, he declared that he was an atheist, though he seemed an agnostic to me).

The comandante likes to base himself on reality, historical events, and political practice. He doesn’t like abstract concepts and theories, except in the case of the exact sciences.

IMPACT OF THE BOOK

This book caused a veritable revolution within the revolution. The original print run of 300,000 copies wasn’t nearly enough. Long lines formed at the doors of bookstores. The police had to be called in to prevent “sharks” from buying up large numbers of the book in order to resell them at exorbitant prices. Around 10,000 people crowded into the square where the book was sold when it was launched in Santiago de Cuba. Why? Because the book was about freedom of religion in Cuban socialism. It was the first time that a communist leader in office had spoken positively about religion and admitted that it, too, could help to change reality, revolutionize a country, overthrow oppression, and establish justice.

Over a million copies were sold in Cuba, which had a population of about 12 million. Leftists and progressive Christians all over the world expressed interest in it, too. Fidel and Religion was translated into at least 23 languages, in 32 countries. Pirated editions were made, of which I never received any copies. In the German part of Switzerland, the book was turned into a play that won the prize for best play of 1987. In Cuba, Rebeca Chávez made an excellent documentary — “Esa invencible esperanza” (That invincible hope) — on the preparation of the book, and it won awards in several international film festivals.

The book’s impact in the communist world led to many invitations for me to attempt rapprochements between various governments and religions, which were often in conflict. I visited Russia, China, Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, East Germany, and Czechoslovakia.

Not only the people of Cuba and other Latin American leftists benefited from the book. So did the Catholic church in Cuba: after a break that had lasted for 16 years, Fidel once again conversed with the Catholic bishops. The way was paved for Pope John Paul II’s visit to Cuba, in 1998.

A COOLING OF RELATIONS

However, it wasn’t all smooth sailing. Fidel was annoyed when, in 1987, the Catholic church sponsored the Cuban National Ecclesiastical Meeting in Havana — equivalent to a local council — and didn’t invite me, even though several other foreigners participated. The Catholic hierarchy contended that all of the foreigners represented institutions, which I did not.

Right after this, the Berlin Wall was torn down, causing a domino effect in Eastern Europe. Cardinal Law, of Boston, visited Cuba near the end of 1989 and preached at the spiritual retreat for Catholic bishops. He exhorted them to follow the example of the Polish bishops. Cuban socialism would soon collapse, too, and the bishops, like new Moseses, should be ready to lead the people from oppression to freedom… At the end of the retreat, the bishops sent a letter to Fidel that contained harsh criticism of the revolution.

The comandante was annoyed, but not by the contents of the letter. When visiting Brazil in March 1990, he told me that he’d never had any illusions about the bishops’ critical position concerning the revolution. What made him angry was the fact that the bishops didn’t deliver the message personally, when the means for direct dialogue existed. As a result, the doors closed again — until the visit of John Paul II, whom Fidel had always admired.

FUTURE CHALLENGES

Now, the Catholic community enjoys a climate of greater freedom in Cuba. No priests or other religious figures are in prison. To the contrary, they are allowed to offer pastoral assistance to prisoners. New members of religious congregations and orders have arrived on the island. Holy days are celebrated publicly. Catholic publications circulate. Theological texts enter Cuba with no difficulty.

What the Cuban bishops lack is a theology that allows them to understand socialism as an absolutely necessary stage on the path toward the kingdom of God. While neither accepting socialism as part of the church nor sanctifying it, nearly 50 years after the triumph of the revolution, they should free themselves of the idea that socialism is an undesired parenthesis in Cuba’s history. This point of view presents capitalism as a system more compatible than socialism with the principles of the Catholic church — especially because the capitalist system recognizes church property and allows the church to privatize education, health care, and other universal rights, denying the poor access to them.

The challenge for Catholics is to preach the gospel within socialism, and not work counter to or outside the system. Jesus didn’t live in an atmosphere that was propitious to him. Palestine in the first century was dominated by the Roman Empire and was inimical to him. Proof of this was that he was murdered, condemned by two political powers.

When preaching the gospel, Christians cannot choose the social regime in which they will work. It isn’t up to them to portray capitalism as the devil or to canonize socialism — or vice versa. Their evangelical commitment should be to the poorest people. If the state — whichever it is — is on the side of the people, its relations with the church will be good. If the state oppresses the people, the church is duty-bound to denounce it prophetically and struggle for justice alongside the oppressed.

Unfortunately, the opposite is usually the case. The Catholic church thinks first of its capital assets, rights, and privileges and fails to act like Jesus, who made himself a servant of and freed the poorest of the poor (Matthew 25:31). There are some exceptions, as in Latin America — especially in Brazil, where the grass-roots ecclesiastical communities and liberation theology led cardinals and bishops, religious figures, and lay preachers to side with those who suffer from injustice, without fearing the consequences of helping them.

This is why Fidel and Religion is still timely 20 years after the publication of its first Spanish edition. Fidel Castro had never before spoken in such detail about his childhood and adolescence, placing more emphasis on his religious training and political convictions than on the relations between Marxism and Christianity. Even though the Sandinista revolution has failed and the Berlin Wall has been torn down, this work serves as a reference for all Christians who seek social justice — and also for all atheists and communists who do the same.

The book helps to destroy leftists’ prejudices and Christians’ fears. It shows that freeing humankind from misery, poverty, oppression, and inequality is an ethical and moral duty of all, whether or not we have a transcendental faith. Faith in human beings is what frees us and makes us more human. It is what God teaches in Jesus. And there’s only one way to express that faith in action: through love, which creates the conditions for God, whom we call Our Father, to be an expression of the truth when, in reality, we have bread and all the conditions required for the entire human family to have a decent life.

São Paulo, October 7, 2005