Читать книгу Homemaking for the Down-At-Heart - Finuala Dowling - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCurtis dished up the porridge and sprinkled in shavings of extra bran. He laid a cloth on a wooden tray. He spread caramel sugar thickly over the steaming surface of the bowl and poured a little cream around the edges. The sugar melted into the hot oats. He placed the bowl on the tray with a jug of milk and a heavy silver spoon.

“What is it?” asked Zoe when he brought the offering to her.

“Porridge,” said Curtis.

“That doesn’t sound very nice.”

“Just try it,” said Curtis. “It’s your favourite. It’s one of your recipes.”

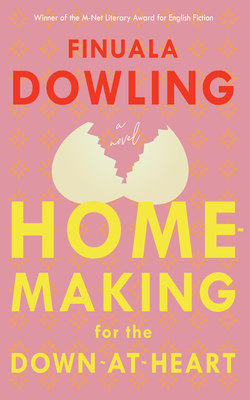

He ran his finger along the books beside her bed till he found the one Zoe had written with her friend Esther. Homemaking for the Down-at-Heart. He read to her: “There is always the possibility that depression can be cured with porridge, especially if you cover it with a crust of sticky brown sugar. Despite its name, a porringer isn’t the ideal serving vessel. You need a wide, shallow bowl so that the sugar or honey melts over the biggest possible area. The bowl should have a generous lip for resting the spoon in moments of thought between mouthfuls.”

“Who wrote that?” asked Zoe.

“You did,” said Curtis. “What do you think?”

“I’m trying to drum up some enthusiasm,” said Zoe.

“This book made you famous,” said Curtis. “Here, I’ll leave it beside you in case you want to read it again.”

“Thank you,” she said, and reached for her glasses. While he pottered about her room, she pretended to read. She could still recognise individual words, of course. She’d read for that doctor, the fool. Read this word, he’d said, and given her a sheet with “TIME” printed on it. I ask you. Like getting a silly Pekinese to examine a wise old Alsatian. But strings of words, whole paragraphs, seemed like mere jabber to her now. She looked at the cover of the book she had supposedly written. It was a bit sticky and stained, especially the kitchen windowsill in the foreground. The garden you looked out onto, the little figures of children playing – that part of the picture was less smudged. It was definitely familiar, like the face of someone you thought you might have been at school with, now distorted by fat, wrinkles and make-up. She hoped this was not another test, like having to spell “world” backwards or say which prime minister you were living under, as if you cared. Smuts was dead.

Curtis took Zoe’s potty downstairs with him and flushed it out. It was Zoe who had taught him that in a house with a lot of stairs, you should never ascend or descend empty-handed. Curtis was used to a farmhouse with one short set of curved steps leading up to the stoep.

Back in the kitchen, he decanted the rest of the porridge into his own bowl and left the pot to soak. He sweetened his breakfast with honey, topped the oats with chopped almonds and used low-fat milk. The slow-release carbohydrates would see him through. He could not understand why women loved cream so much, when it was so bad for them. His enjoyment of food was principally linked to its fuel efficiency.

Pia came in wearing a pair of absurdly fluffy pink slippers. “I suppose you’ve been up for hours,” she said, filling her cereal bowl.

“I think you’re the only person in this household who sleeps well,” he said.

Pia sat at the kitchen table and studied a glossy hypermarket advertising supplement. Here were other people’s lives: their lounge suites and lawnmowers. Pia turned to the toy section. It still excited her to see the dolls and furry animals. Their eyes shone out at her, willing her to animate them. She could give them lives and histories. She could build them cosy homes or set them adventurous tasks. The Baby Born doll stared intently at Pia. The blurb said that she wet herself and cried. You had to change her nappy. With a baby, Pia could be someone else. She knew who she wanted to be. An American woman, crying. Why? Because there was something terribly wrong with her baby. Baby Born. Or the story could be something ridiculous. She could wear high heels and drop the baby off at daycare, saying: Please keep my child away from mohair, she’s already had to have an operation to remove a huge fur ball.

The surge of life filled her. There were so many things to do, people to be. There was the novel she’d been writing. She thought about what she’d written so far. She knew that something horrible was going to happen next, only she wasn’t sure what.

Curtis finished his breakfast and observed Pia in her reverie. “A penny for your thoughts,” he said.

“I’m just thinking about the novel I’m writing.”

“Great! What’s it called?”

“The Shrewd History of Lorena Johnston.”

“What a marvellous title.”

“Yes, and what does ‘shrewd’ actually mean?”

“Sort of like calculating all the time what will be best, how to win.”

He took their bowls to the sink. “Why don’t you get dressed now so we can clear out the shed like we planned?”

“In two toots!” said Pia.