Читать книгу Caravaggio - Félix Witting - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

His Fate

The Early Years and Departure for Rome

Departure for Rome

ОглавлениеSome years later, aged twenty-one, Caravaggio went to Rome where, undoubtedly helped by his uncle who already lived in the city, he lodged with a landlord who lived a modest life, Fr Pandolfo Pucci de Recanati, an acquaintance of Monsignor Pucci, beneficiary of St Peter’s Basilica in Rome. A document left by the historian W. Kallab indicates that the artist lived in comfortable conditions, but complained about certain aspects of domestic life, in particular about the meals which consisted of salad and chicory as starter, main dish and dessert. This is partly why after some months he left the home of Pandolfo Pucci, to whom he gave the nickname “Monsignor Insalata”. This same document indicates that the host commissioned from the young painter several works with religious subjects which were intended for his home town. It was at this time that Caravaggio fell ill and, having no money, he was admitted to the hospital of Santa Maria della Consolazione where during his convalescence he painted numerous canvases for the Prior.

Caravaggio’s experiences in Venice were still strongly influencing him whilst in Rome, and he continued to concentrate on acquiring his own majestic style. That was the aim behind, and the result of, his apprenticeship in the studio of the Cavalier d’Arpino. In 1593 Caravaggio entered the studio of the successful painter Giuseppe Cesari d’Arpino, also known as the Cavalier d’Arpino. Baglione tells us that “he stayed with the Cavalier Giuseppe Cesari d’Arpino for several months.”[23] Caravaggio turned to him in order to find connections to artistic circles in the Eternal City. Guiseppe Cesari has left frescos in the Trinità de’ Monti, in the chapel of the Palazzo di Monte Cavallo and – his best work – in the Capella Olgiati in San Prassede. In the Capella Contarelli in San Luigi de’ Francesi, where he started the frescos, Caravaggio was to become his successor.[24]

D’Arpino worked mostly as a fresco painter, and tried to pass on to his pupil the somewhat grandiose side of Romanesque art, from which base he could expand the means and resources at his disposal. Caravaggio’s works show that he neither ignored the advice of his artistic masters, nor the works of other artists, often even those of a heterogeneous style. He studied Antique art with diligence and emulated Michelangelo Buonarotti. He even undertook the painting of the sign of his brother Frangiabigio Angelo’s perfumery, in this way further developing genre painting,[25] as we can see in The Fortune Teller.

The Ecstasy of Saint Francis, c. 1594–1595. Oil on canvas, 92.5 × 128 cm. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford (Connecticut).

The Cardsharps, c. 1594. Oil on canvas, 94.2 × 130.9 cm. Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth.

The Cardsharps (detail), c. 1594. Oil on canvas, 94.2 × 130.9 cm. Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth.

However, save a tendency for grandness, the Cavalier d’Arpino, with his more generalistic style, had very little to pass on to the painter from northern Italy. Even so, at that time Giuseppe Cesari was considered one of the most influential artists in Rome. One imagines that an unknown protector recommended Caravaggio to Cesari, opening the door to his prestigious studio. Whilst the Cavalier d’Arpino concentrated on frescos, Caravaggio, as Baglione clearly states, devoted himself first and foremost to oil painting.[26] He was employed “to paint flowers and fruit”. The still-life genre, which was very fashionable in Lombardy, began to evolve towards a very realistic representation where each detail was highlighted as if it had been magnified by an optical lens. The representation of natural elements predominated in the first works of Caravaggio: Boy with a Basket of Fruit, Boy Peeling a Fruit, and Basket of Fruit. The sensuality of the two boys in these works is evident, though the declaration by certain critics that these paintings are odes to homosexuality seems somewhat exaggerated and simplistic. It is true, however, that slightly parted lips charge a painting with eroticism, and Caravaggio did at times hide messages within his works. Thus the fruit that the boy is peeling could be a bergamot, a bitter orange, the symbol of Universal Love. During the Middle Ages, it was not unusual for a husband to put on vermillion robes, which Goethe declared in his treatise “represent the colour of extreme ardour as well as the gentlest reflection of the setting sun.”[27] Therefore this painting could symbolise the transition from child to adult, with the bitter taste of the fruit representing the end of innocence.

Nevertheless, Nature was not, for Caravaggio, the great protector and dominator of mankind that so many other artists took it to be. Nature provided him with no feelings of exaltation nor of lyrical depression, it did not flood his soul with joy or fear, it inspired neither adoration nor meditation within him. It offered him simply a framework, a theatrical scene within which to place his characters or a series of objects, which he could reproduce faithfully on the canvas, conforming to the fundamental principles of naturalists. He was aiming, according to his own words, “to imitate the things of nature,” while at the same time conforming to the standards set by his Lombard masters. As previously noted, Caravaggio himself said on this subject: “A painting of flowers requires as much care as one of people.” Although Merisi pronounced this himself, he did later admit, conforming to the general opinion of the time, that the human form could never be compared to simple fruit and vegetables. Beyond the prevalence of vegetables, Caravaggio’s contemporaries must have been impressed by the realism of his paintings. The sensuality which emanates from Caravaggio’s early works deeply moves the spectator from the first viewing. However, his first masterpiece, the soft and luminous landscape of the Rest on the Flight to Egypt – which clearly reminds us of the style of Giorgione – evokes more than the simple sensory impressions of the outside world. The serene sky reflected in the calm water, the caress of light on the oak tree, the cherry laurel and the white poplars; the tender flair of the marshland reeds with their frayed leaves surrounding the three-leaved brambles have been brought together in order to create a harmony, a source of beauty to which the young artist was sensitive. In addition, Caravaggio paid particular attention to the expression of the face, as one can see in the apparent pain of the child in Boy Bitten by a Lizard. The instantaneousness of the boy’s reaction and the mask of pain on his face are so unmistakeably realistic and accurate that they cannot help but evoke feeling in the viewer. The working of the facial expression is remarkable and the intensity of feeling within the work is extraordinary. Throughout his career, Caravaggio worked ceaselessly at the expressions of feeling of his subjects.

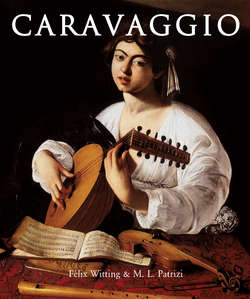

The Musicians, c. 1595. Oil on canvas, 92.1 × 118.4 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The Musicians (detail), c. 1595. Oil on canvas, 92.1 × 118.4 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The Fortune Teller (first version), c. 1595. Oil on canvas, 115 × 150 cm. Musei Capitolini, Rome.

The Fortune Teller (second version), c. 1595–1598. Oil on canvas, 99 × 131 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

After several months, according to Baglione, Caravaggio became independent and occupied himself with painting some self-portraits in the mirror. There are several works today which could be examples of these, but their attributions are still debatable.[28] Amongst the impressions collected in Venice, for example, there was a painted self-portrait made up of warm tones, essentially brown in colouring, with which the thick white paint of the collar and clothes contrasted strikingly, and a soft, gentle face despite his noted temper; the sword “which sat so loosely in its sheath”. The somewhat heroic golden tone sets the painting within his early Roman period. Another self-portrait, at one time in the collection of the Duke of Orleans, is currently missing.[29] It showed the artist in a beggar-like outfit, seen almost entirely from behind in a lost profile pose, holding a mirror in front of him, in which his weathered but not unattractive face is reflected; next to him is a skull. He next painted Baglione as Bacchus with grapes “with much diligence, but little sentiment”.[30] This painting, which was at one time lost, was seized by tax officials from the Cavalier d’Arpin in 1607. It can now be found in the Galerie Borghese, where it has been for several years. Caravaggio may have represented himself here as the sick Bacchus, excited to be recreating reality. The youth’s pale and wan complexion gives away his poor health. Is this the malaria, as many critics like to think, that debilitated Caravaggio? Whether or not this is so, the dubious whiteness of the cloth indicates the painter’s convalescence. The fruit in the foreground is also noticeable as a silent witness to the still-lifes of Caravaggio’s early work. Likewise, the fact that he placed this fruit in the foreground, rather than the god Bacchus, betrays the artist’s typical will to go against all the supposed “rules” of the time. Sensuality reigns in this painting, and the exposed shoulder of the figure only serves to reinforce this impression. Gorging himself on grapes, the youth turns towards the viewer as if in invitation. The realism in this painting is striking, and one can see the extent of Caravaggio’s mastery of the art of feeling and suggestion. The figure’s contrapposto pose highlights the influence of the statuary art of the artist’s namesake, Michelangelo Buonarotti.

Bacchus, c. 1596. Oil on canvas, 95 × 85 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

Basket of Fruit, c. 1594–1598. Oil on canvas, 47 × 62 cm. Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan.

Caravaggio next worked with Monsignor Fantin Petrignani, who allowed him the use of a room in which to paint. Later, around 1595–1597, thanks to the art dealer Maestro Valentino, his work caught the attention of Cardinal del Monte, and from then on the artist was under his protection.[31] He was welcomed with magnanimity into the Cardinal’s home, where he benefited from this new environment. His entry to the palace, where he rubbed shoulders with scientists, in particular Galileo, musicians and artists in pursuit of innovation, allowed him to develop new forms of expression. He painted a “group of young musicians, portraits painted from life, very well made” for the Cardinal, which launched a new form of genre painting with music as the subject, which was common right into the eighteenth century. Of course there were occasional isolated forerunners on this subject, notably a concert (from the fifteenth century) with a mandolin player and a man and a woman singing, pictured from the waist upwards, attributed to Ercole dei Roberti.[32] In the same way, on the theme of The Prodigal Son, there are several similar subjects in the Nordic art of the early sixteenth century, for example in the works of Hemessen and Lucas van Leyden.[33] As for members of the Venetian School, they had depicted similar subjects in a nobler way, such as Giorgione’s depiction of a concert in the Palazzo Pitti and another concert by one of Titian’s successors in the National Gallery in London. But Caravaggio used his own means to lift this genre to the height of an almost tendentious monumentality. A number of such Musiche – the attribution of which are not completely certain – are thought to be in English private collections, such as a concert with an old man with a lute, a younger man with a flute and a singing boy in the collection of Lord Ashburton.[34] In Chatsworth House there is a concert of guitar and flute players with a singer, who is holding a full glass in his hand, which was previously attributed to Caravaggio but is now thought to be the work of one of his disciples, the great Valentin de Boulogne.[35] In Kassel there are two similar depictions of concerts.[36] Baglione mentions another painting, depicting a young man with a flute, which Caravaggio may also have made for the Cardinal, but whose attribution is still contested. In this painting he intensified his skill in imitation in competition with the Nordic artists, as in all the paintings of this genre. Remarkable also in the work is the vase of flowers, in whose water is reflected the window and other objects in the room. Baglione states that these works were created “with an exquisite application”, recognising the great art of his adversary in the courts. The Musicians highlights the elegant setting that would evolve within Caravaggio’s work from then on. Vegetables, fruit and other still-life objects were exchanged for lutes and violins. However, this genre is in no way naive. Cupid, who is clearly identified by his wings and arrows, only serves to accentuate the sensuality that emanates from the figures. The fabrics draped over the musicians hide the essential parts, but the disordered cloth is equivocal in its nature, as is the lascivious gaze of the watching figure in the background.

Rest on the Flight into Egypt, 1596–1597. Oil on canvas, 133.5 × 166.5 cm. Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome.

Rest on the Flight into Egypt (detail), 1596–1597. Oil on canvas, 133.5 × 166.5 cm. Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome.

Rest on the Flight into Egypt (detail), 1596–1597. Oil on canvas, 133.5 × 166.5 cm. Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome.

Over the years, the representation of nature in which Caravaggio excelled was replaced by other themes, as outbursts of violence and aggressiveness were taking more hold of his life and work. The painter essentially endeavoured to reproduce the emotions and passions of mankind, such as vice, crime or human suffering, beyond any mere aesthetic effect.

The recurrent themes of his work echoed his mood and as a musical chord can be deconstructed, one could also deconstruct the themes of his paintings into notes: those of darkness, blood, scoundrels and gamblers, cheats and Bohemian thieves. These notes are accompanied by a background rhythm of subjects and musical episodes, while unrestrained bursts of comedy bring a discordant note into solemnly tragic or sacred events.

Despite the naive character of the painter’s first biography, it is undeniable that Caravaggio’s personality traits attracted him towards an obscure style of painting (or “Tenebrism”), his works to be enlivened by the breath of Realism. The obscure depth of his work is filled with the intimate feelings of their creator. One cannot exclude the idea that his taste for strong contrast of shade and light may correspond to the use of a long-matured technique. This technique seeks to evoke in the spectator an emotion in harmony with the dramatic tonality of the representation, by imprinting upon the forms an energetic relief favourable to a realistic expression of his art. But the consistency of his style and the profusion of shade, despite some technical loopholes, suggest with reason the artist’s predilection for contrasting colours reflecting his “brilliant and tormented” temperament, as Bellori recorded.

During these decisive years for his art, he produced numerous canvases. The work he carried out for the Contarelli chapel established his reputation and the prelates of Rome decided to entrust him with the realisation of large religious paintings. It was not unusual for his commissioners, as princes and prelates engaged in a game of “cultural rivalry”, to order several versions of the same subject from the artist to enrich their collections with the same masterpieces; scenes of the Nativity, the Supper at Emmaus, Saint Jerome, David and Goliath, The Fortune Teller, The Card Players and Mary Magdalene were all such subjects. He would borrow certain characters from one painting and place them in another composition, such as the old woman with her head in her hands in a gesture of terror, a figure that appears in both Burial of Saint Lucy and The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist. Another old woman seen in profile, reminding us of La Vecchia by his great influence Giorgione, is present both in The Tooth Puller and in Judith and Holofernes.

Penitent Magdalene, 1596–1597. Oil on canvas, 122.5 × 98.5 cm. Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome.

Saint Catherine of Alexandria, c. 1597. Oil on canvas, 173 × 133 cm. Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.

The painter could also, unbeknown to him, repeat the same pictorial gesture or, by simple predilection, favour a line, a form, a type of light, or a contrast he judged interesting. This led him to re-employ certain expressive details such as the very sensual incline of the neck of certain male and female figures, seen in such works as The Musicians and Rest on the Flight into Egypt, or the details of a flexed hand visible in the painting of Narcissus and The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist. Although these details have contributed to the definition his style and allowed art historians to identify certain paintings as being by him, the attribution of certain works, such as Ecce Homo and The Tooth Puller, still remains uncertain. Indeed, his very personal techniques, notably the incisions made in the thickness of the undercoats, the brown border which he left around his figures, the dark backgrounds that grew more and more refined, and the light delivered by a vertical or lateral source, creating highly-contrasting zones of light and shade, were not applied systematically by Caravaggio, while his successors sometimes used the same methods.

Favouring realism over the idealisation of biblical characters, he went as far as placing Saint Matthew sitting astride a stool, turning his roughly-painted feet towards the spectator. He painted the swollen, obscene body of a drowned woman in his representation of The Death of the Virgin and he symbolised, it seems, Architecture as a figure with the appearance of a woman from Trastevere holding a compass, or even Mary Magdalene with the features of common woman wearing dishevelled clothes and with her plaits undone. All these attitudes can be interpreted as systematic executions of a naturalistic vision which was the goal of his art. He also painted The Conversion of Saint Paul, in which a horse occupies almost all the canvas, along with a representation of Saint John the Baptist as a child in the desert playing with a sheep, in which he refrains from giving even the least spiritual dimension to the work. In The Supper at Emmaus, the innkeeper wearing a hat is probably an eminent associate of the painter, possibly Cardinal Barberini, the Cavalier Marino, or even Alof de Wignacourt, though we cannot be sure. He even painted a Trinity – now lost – representing two men sitting on a seat under which a pigeon seeks refuge, men who he probably rubbed shoulders with in the inn. By liberating himself from the conventions of religious iconography, his work was a decisive turning point in the representation of the stories of the saints and biblical figures, characters to whom he gave realism and humanity.

23

Baglione, op.cit., ch.1.

24

Baglione, op.cit., ch.1.

25

To be compared with J. Meyer, op.cit.

26

Baglione, op.cit., ch.1.

27

Goethe, Traité des couleurs, 1810, Triades, 1996.

28

Baglione, ch.1.

29

J. Meyer, op.cit., p. 623.

30

Baglione, Vita di Michelangelo da Caravaggio.

31

Baglione, op.cit., ch.1.

32

Exhibited at Burlington Fine Arts Club, 1894, illustrated catalogue pp.l, VII.

33

In Berlin (Museum III, 76) and Wilton House. – Lomazzo mentions, in his Trattato, 1584, p.439, that mural paintings can be found in several Italian osteria (both indoors and outdoors) with representations of ruffians, drinkers, gamblers in Milan – Compare with N. Bertolotti, Artisti belgi et ollandesi a Roma, Firenze, 1880. – The genre paintings by Dosso Dossi are also mentioned (oval paintings eaters, drinkers and musicians at the gallery in Modena, bambocciata in the Palazzo Pitti (n° 148) in Florence. In Delle Maraviglie dell’arte I, p. 79, Ridolfi talks of Giorgione’s genre paintings on façades (frescos).

34

Waagen, op.cit., II, p. 82.

35

Ibid., I, p. 249.

36

Compare with J. Meyer, Künstlerlexikon.