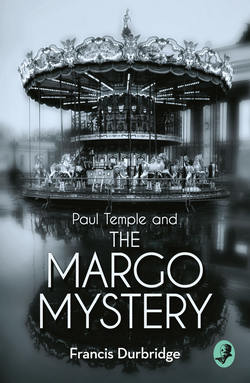

Читать книгу Paul Temple and the Margo Mystery - Francis Durbridge, Francis Durbridge - Страница 5

CHAPTER I The Coat

ОглавлениеThanks to a cab driver with the nerve of a Grand Prix racer Paul Temple caught the morning flight from New York to London by the skin of his teeth. As a Concorde passenger he received VIP treatment and was hustled through the departure formalities. Less than an hour after leaving his hotel on Fifth Avenue he was in his window seat watching John F. Kennedy Airport drop rapidly away as Concorde soared towards her cruising height. Some other passengers must have cut things even finer, for the seat beside him had remained empty.

He listened patiently to the stewardess going through the familiar demonstration of the emergency equipment, waiting for the illuminated sign to be switched off so that he could unfasten his safety belt. As the Captain finished his reassuring announcement he made his way forward to put through the telephone call to London which he had booked on boarding.

One of the stewardesses, who had put on her in-flight overall, stood aside to let him pass. Her smile was not purely automatic. It was a pleasure to see someone whose style matched that of the aircraft. Temple, with his well-cut clothes, tall build and clean-cut features looked as British as the Rolls-Royce engines that were driving them through the air faster than a bullet leaving a rifle.

Temple’s decision to return home had been made last thing the evening before and his wife Steve would need some warning that he would be arriving two days early.

When he returned to his seat he found that a youngish man had ensconced himself in the empty place. He smiled apologetically and swung his knees sideways to let Temple pass.

‘I hope you don’t mind. I saw that this seat was empty.’ The accent was American, but suggestive of Boston rather than the Bronx.

‘Not at all,’ Temple said, removing The New York Times from his seat before he sat down. ‘I thought someone must have missed the plane.’

‘Oh, I have a seat further back. I flew in from California overnight and had a couple of hours’ wait at Kennedy. Nice to think we’ll be in London just about the same time as we left New York. Your Concorde sure is a fantastic aircraft.’

‘Yes, and this new telephone link by satellite is a great advantage. I’ve just been talking to my wife.’

‘Mrs Temple doesn’t come on these trips with you?’ The man laughed when he saw Temple’s surprise. ‘You don’t remember me? My name’s Langdon. Mike Langdon. We met in Hollywood, Mr Temple.’

‘Did we?’ Temple turned to look at his neighbour more closely. He was wearing a lightweight suit and his confident manner was that of a hard-thrusting businessman who does not mind cutting a few corners to achieve his targets. His dark curly hair was cut close to his head and he must have found time to shave during his wait at Kennedy, for his cheeks were smooth. Temple could often tell as much about a person from his hands as from his facial features, but Langdon held his hands firmly folded in his lap as if determined to keep them strictly under control.

‘You don’t remember?’

‘I’m sorry.’ Langdon was holding his gaze. ‘I’ve met so many people during these past weeks—’

‘Yes, of course.’ Langdon smiled, remembering some scene that Temple had forgotten. ‘I was at that party the film people gave you – me and about two hundred others.’

‘Yes.’ Temple smiled in reply. ‘That was quite a party, wasn’t it?’

‘It sure was.’

‘Are you in the film business, Mr Langdon?’

‘No.’ Langdon glanced down to adjust the cuffs of his shirt, making sure that they protruded just one quarter of an inch. ‘I’m with a publishing firm in New York, Talbot and Ryder. It’s only a small outfit, but we do very nicely. I’m sorry we don’t have your books on our list, Mr Temple, but I guess we can’t afford the advances the big boys put up. How did the lecture tour go?’

‘Oh, very well, thank you, but it was a bit wearing at times.’

‘I’ll bet!’ Langdon agreed emphatically. ‘Our authors hate ’em. Still, they’re first-rate publicity.’

The conversation was interrupted as two stewardesses came along with the Concorde ration of vintage champagne. Langdon shook his head and insisted on a Scotch on the rocks.

‘Is this your first trip to Europe?’ Temple enquired, savouring his Veuve Clicquot. The aircraft had climbed through cloud and was now flying over a cotton-wool landscape under blue skies.

‘No. I’ve been over many times before. I was in Paris two weeks ago.’ Langdon turned sideways in his seat, swirling the ice round in his glass. Temple sensed that he was now about to learn why Langdon had wanted to sit beside him. ‘Mr Temple, have you heard of a young man called Tony Wyman?’

‘No, I don’t think so. Should I have done?’

‘Well, I understand he’s fairly well-known in your country. He’s a pop singer.’

‘Tony Wyman?’ Temple shook his head. ‘Is he a friend of yours?’

‘No.’ Langdon gave a short laugh. ‘And I doubt whether he’ll turn out to be one, either.’ He eased a little closer and leant his forearm on the armrest between them. ‘Mr Temple, I’ve got quite a problem on my hands and I’d sure like to talk about it. Is that okay by you?’

‘Why, yes.’ Temple, who was used to this kind of approach, smiled wryly. ‘Go ahead.’

‘About two years ago my firm was taken over by an Englishman called George Kelburn. If you don’t know Kelburn personally, you’ve probably read about him.’

‘Yes, I’ve heard of Kelburn. He’s a north-country chap, reputed to be worth millions.’

‘That’s right. Well, when Kelburn took our firm over he made me the Number One boy. He’s a blunt, ruthless sort of guy, but we’ve always got on well together.’

Temple thought Langdon looked as if he was well able to handle a blunt, ruthless sort of guy.

‘He’d be a good deal older than you?’

‘Yes, he’s about sixty, maybe sixty-two or three. I’m not sure.’

Langdon screwed his eyes up against a sudden dazzle. As the plane banked the sunlight was reflected into the cabin off its gleaming wing.

‘Go on, Mr Langdon,’ Temple prompted.

‘Well, Kelburn’s first wife died some years ago and he married again – a woman a lot younger than himself. He has a daughter, Julia, by his first wife. Julia’s twenty-one – young, attractive and hopelessly spoilt.’

‘Not an unusual story,’ said Temple with a smile.

‘No, I suppose not, but – well, to cut a long story short, Julia’s got herself tangled up with this night-club singer, Tony Wyman, and she’s told her father that she intends to marry the guy.’

‘And Kelburn’s against it?’

‘Against it?’ Langdon looked deadly serious. ‘Kelburn’s going to stop that marriage if it’s the last thing he does.’

‘Yes, but – how do you fit into all this, Mr Langdon? If you’re just a business associate of Kelburn’s…’

‘That’s just the point,’ Langdon interrupted, with exasperation. ‘I don’t fit into it! But Kelburn sent me an SOS, and there was nothing I could do about it.’

‘You mean, he wants you to try and influence her to…’

‘Exactly! Julia and I have always got on well together, so he wants me to talk to the kid and try to persuade her to throw the boyfriend over.’

‘Do you think you’ve got much chance?’

‘None.’ Langdon shook his head morosely. ‘I’ve got no special influence with her, and according to all accounts she’s nuts about this Tony Wyman.’

‘You seem to be in quite a spot.’

‘You can say that again! Well, you’re used to other people’s troubles, Mr Temple! What would you do if you were in my shoes?’

Temple had warmed to Langdon, whose frank helplessness was rather disarming. The problem was a pleasantly banal one, after the murders and other vicious crimes which he was usually called on to solve. ‘Frankly, I don’t know what I’d do.’

‘If I refuse to help Kelburn he’ll put me on the spot businesswise – there’s no doubt about that, I know Kelburn. On the other hand, if I get mixed up in it and make a mess of things, which is more than likely, it isn’t going to do me any good either.’

A stewardess was moving back along the cabin, collecting the empty glasses. Temple finished his champagne and placed the glass on the folding table ready for her.

‘And how does Kelburn’s wife react to all this?’

‘Oh, Laura takes the point of view that Julia’s twenty-one and she’ll do what she likes, anyway.’

‘I see.’

‘This whole business has turned up at a very awkward moment, so far as I’m concerned. I’ve had a hectic time just lately – been in ten countries in two months, and right now I’m ready for a holiday, not a first-class family squabble.’

‘Well, there’s no point in anticipating trouble, Mr Langdon,’ Temple told him reassuringly. ‘Perhaps when you get to London you’ll find the situation has straightened itself out.’

‘I certainly hope so.’

‘Anyway, I’m in the ’phone book. If you feel I can help you at any time, give me a ring.’

‘Well, now, that’s very kind of you, Mr Temple.’ Obviously delighted, Langdon stretched out his free hand and insisted on shaking Temple’s. ‘I do appreciate it, sir. I certainly do!’

The stewardess leant across him to pick up Temple’s glass. ‘Will you be returning to your seat, sir?’ she enquired, ‘or remaining here? We shall shortly be serving lunch.’

‘Oh, I’d better get back to my own seat,’ Langdon said, rising. ‘And thanks again, Mr Temple. I may take you up on that offer.’

Steve returned to the flat at about two thirty after lunching in the West End. The flat always seemed so empty when Temple was away, and she began to wish she had accepted her friend’s invitation to go and see the new exhibition at the Hayward Gallery. She went into the bedroom and unpacked the new dress she had bought. She wanted to surprise Paul with something really smart when he came back from his lecture tour. As she held it against herself and studied the effect in the long mirror she decided that a new pair of shoes and a handbag were essential to match it. Rather than hide it away in the long cupboard, she hung it on the back of the door where she could see it and wandered aimlessly into the sitting-room.

The trees in Eaton Square were beginning to bud and the city birds had already started to prophesy spring. A couple of the early daffodils she had bought to brighten the place up had begun to wilt. She had picked them out of the vase and was throwing them into the waste-paper basket when Charlie came in. He was carrying a cup on a tray.

‘Thought you might like a cup of coffee.’

‘Oh, thank you, Charlie. Just put it down on the table.’

Charlie was the Temples’ driver, cook, odd-job man and watchdog. His familiarity sometimes verged on impertinence but he was loyal and faithful as a spaniel. The forty-year-old Cockney had been with them for more years than any of them cared to remember and had his own sitting-room and bedroom beyond a door whose threshold neither Paul nor Steve would have presumed to cross. The only disadvantage about Charlie was his unfortunate lack of dress sense. Steve tried not to show her disapproval of the lumberjack shirt and the too tight check trousers.

‘What time is it, Charlie?’

‘Just gone ’arf past two,’ said Charlie, setting the cup and saucer down on a low table. ‘Cream’s in it already but I didn’t put any sugar, like you said.’

‘Only half past two. How slowly the days go! I thought it was later than that. In New York it must be nine thirty.’

Charlie paused, knowing that she needed company. ‘Yes, I suppose it will. Five hours back. Do you think Mr Temple will have had breakfast yet?’

‘Well, I should hope so, Charlie. He promised to get through his schedule as quickly as possible.’

‘When are you expecting him back, Mrs Temple?’

‘Some time next week, if all goes well.’

Charlie stared sympathetically at her dejected face. ‘I’ll bet you’ll be glad.’

‘That’s the understatement of the year. It seems as if he’s been away for months.’

‘Four weeks and a day.’ Charlie saw the discarded daffodils in the waste-paper basket and went over to pick them up. ‘You know, I can’t understand why you didn’t go with him. You usually—’

‘Have you ever been to America on a lecture tour, Charlie?’

‘No,’ Charlie admitted, after a moment’s thought. ‘Can’t say as I ’ave.’

‘Twenty-two towns in four weeks. That’s not my idea of –’ She stopped as the telephone in the hall began to ring. ‘Oh, see who that is, Charlie, will you? If it’s those people who want to clean our carpets say I’m not in.’

She heard Charlie pick up the telephone and give the number. Almost at once he called: ‘Mrs Temple! Quick! It’s Mr Temple.’

Steve ran to seize the receiver from him. ‘Paul, darling! Where are you?’

‘About thirty thousand feet over the east coast of Canada. I’m on Concorde.’

‘But Paul, how on earth—? I didn’t know you could—’

‘Listen, Steve. How are you?’

‘I’m fine. Looking forward to next week.’

‘I’ve got news for you. I’ve finished my tour early and I’m on my way back. We’re due to land at London Airport at seven fifteen.’

‘Oh, that Concorde! But how are you able to ’phone me? The line’s so clear.’

‘Don’t worry about that. Now, you’ve got the message? I’ll be home tonight.’

‘Seven fifteen at London Airport. Bet your sweet life I’ll be there!’

‘There’s no need to meet me, darling. I can take a taxi.’

‘Just you try and stop me. What’s the flight number?’

‘Just ask for Concorde, Terminal Three. Goodbye, Steve. See you at Heathrow.’

Charlie was alone in the flat at a quarter to eight when the telephone rang. He came out of the kitchen, wiping his hands on the faded blue and white housemaid’s apron he always wore when he was cooking.

‘Mr Temple’s residence.’

‘Is that you, Charlie?’

‘Mr Temple! Where are you?’

‘I’m at the airport. Is Mrs Temple with you?’

‘Why no! I thought she’d be with you, Mr Temple. She left here two hours ago.’

‘Did she take the car?’

‘Yes—the MG Metro.’

‘You’re sure she knew the time and place?’

‘Yes, she knew the time and place all right. She’s been talking about nothing else all afternoon.’

‘I see.’ Temple’s tone was worried. ‘Did she say whether she had any calls to make?’

‘No, but I don’t think she had.’ Charlie was certain that Steve had had no other thought in her mind except to meet her husband. ‘I hope there hasn’t been an accident…’

‘Yes, I hope so too, Charlie,’ Temple said gravely. ‘I’ll see you later.’

‘Very good, sir.’ Unusually subdued, Charlie replaced the receiver.

The homecoming dinner prepared with such care by Charlie had proved to be wasted effort. On arriving back at the flat Temple had declared himself unable to swallow a mouthful after the meal he had eaten on Concorde, and five hours after she had left for the airport there was still neither sight nor sound of Steve. Charlie had salvaged what he could and stored it away in the deep-freeze for some future occasion. He was in his bed-sitter watching the TV commercials that preceded the ten o’clock news when there came a long ring on the doorbell followed by an authoritative rat-tat-tat on the knocker.

Charlie, divested of his apron and wearing a jacket which noticeably failed to match his trousers, went to open it. Of the two men standing on the landing outside he was already familiar with one. Sir Graham Forbes was the kind of Englishman who had been formed by the successive processes of school, university, military service and public office. With his broad shoulders, bristling grey moustache, bushy eyebrows and a certain aura of unshakable confidence he was still impressive enough to attract the glances of women.

‘Good evening, Charlie,’ he said, as one greeting an old friend.

‘Good evening, sir. Mr Temple’s expecting you.’

‘Any news?’ Sir Graham asked, as he stepped into the hall.

‘No, sir. I’m afraid not.’

The heavily built man with Forbes was at least fifteen years younger and of a very different type. He was soberly dressed with a plain tie and well-polished black shoes. Charlie, who was at heart a downright snob, could see at a glance that he had made his way in the world by his own unaided efforts, assisted by no advantages of family or money. Charlie was not endeared by the way those hard eyes swept over him, missing not a detail of his dress and physical features. He had the uncomfortable feeling that he was being checked against some rogues’ gallery that the police officer carried in a computer-like mind.

‘In here, Sir Graham,’ he said, fussing over the taller man and ignoring the other. ‘Mr Temple’s in the sitting-room.’

Temple, who had also been watching the ten o’clock ITV news, half expecting to hear that there had been some horrific pile-up on the M4 between London and Heathrow, switched the set off and came across the room to meet his visitors.

‘Come in, Sir Graham. It’s very kind of you to come at such short notice.’

‘My dear fellow, I’d have got here sooner only I was already half-way home from my club when your message came through. And when Steve is concerned—’

‘I understand there’s no news, Mr Temple,’ the police officer said, anxious to make the point that he too had forsaken hearth and home to accompany Sir Graham.

Temple turned towards him and the eyes of the two men met with mutual appraisal and respect. Raine, of course, had known Temple’s reputation as a criminologist as well as an author, even before the briefing Forbes had given him in the car.

‘No, I’m afraid not.’

‘This is Superintendent Raine, Temple.’ Forbes put a friendly hand on the Scotland Yard man’s shoulder. ‘I don’t think you’ve met before.’

‘No, I don’t think we have. Though I read about your handling of the Belgrave Square siege.’ The two men shook hands, still measuring each other with their eyes. Temple assessed Raine as thorough and methodical but perhaps a little unimaginative. ‘How do you do, Superintendent.’

‘Pleased to meet you, Mr Temple.’

‘Sit down and I’ll get you a drink.’

‘No, no. Don’t worry about drinks.’ Forbes brushed the offer aside, to Raine’s evident disappointment. ‘Temple, tell me, have you checked the hospitals?’

‘I’ve checked every hospital within thirty miles of the airport,’ Temple said wearily. ‘It took me the whole evening.’

Raine had seated himself on the front edge of one of the easy chairs. ‘I understand you found Mrs Temple’s car?’

‘Yes, Superintendent. It was in the car park at the airport. The attendant remembered her arriving – about half an hour before my plane was due. She’d left her coat in the back of the car, so she couldn’t have intended to go much further than the lounge, or maybe the restaurant.’

‘I take it Mrs Temple didn’t leave a note for you, sir, or anything which might…’

‘No. I’ve been through the place pretty thoroughly, and apart from a telephone message there’s nothing – absolutely nothing.’

Forbes, who had taken up his customary position in front of the fireplace with legs astride, asked: ‘What was the telephone message?’

‘It was on the pad upstairs. It simply said: “Tell P.” – which is obviously me – “about L.”’

‘Who’s L, Temple?’

‘I don’t know. But I don’t think it’s important, Sir Graham. According to Charlie, the message was written several days ago.’

‘Well, I’m sorry, Mr Temple,’ Raine commented in his deliberate way, ‘but it looks as if we shall have to face the facts. The only explanation I can see is that your wife’s been waylaid by someone. Now the question is…’

He was interrupted by the ringing of the telephone out in the hall. Temple exchanged a quick glance of hope with Forbes before he went out to pick the receiver up.

‘Hello?’

He could hear the bleep-bleep, indicating that the call was coming from a pay ’phone. There was a clunk as a coin was pushed into the slot. Then Temple heard a man’s voice, muffled but obviously in the same call-box.

‘All right. Go ahead. Talk to him now…’

‘Hello!’ Temple repeated impatiently. ‘Hello, who is that?’

There was a pause, and then: ‘Is that you, Paul?’ The woman’s voice was so weak that he hardly recognised it as Steve’s.

‘Steve! Is that you, Steve?’

‘Paul, can you hear me?’

He could tell from her voice that she was very frightened. ‘Steve, where are you?’

‘Don’t worry, dear.’ Scared though she was, she was trying to reassure him. ‘There’s nothing to worry about…’

‘Yes, but Steve,’ Temple cut in, unable to mask his impatience, ‘where are you speaking from?’

‘I’m…perfectly all right…’

‘Steve, listen!’ Temple was gripping the receiver. ‘There was a man on the ’phone, I heard his voice…Who was it?’

‘Paul, don’t try and…’ Steve’s voice was fading, as if someone were pulling the receiver away from her.

‘Darling, please tell me…Where are you?’

‘Oh, Paul…’ The cry was barely audible. Before Temple could speak again the maddening bleep-bleep had started once more.

‘Oh, my God!’

‘What’s happened?’

Temple looked round to find Raine at his shoulder. ‘The line’s gone dead.’

‘Replace the receiver, Mr Temple – in case she rings back.’

Temple realised that he was still trying to squeeze some response out of the telephone. With deliberate control he replaced it on the cradle.

Forbes had come to the doorway of the sitting-room to listen to Temple’s side of the brief conversation. ‘You said something about a man, Temple. Was there someone with Steve?’

‘Yes. I heard a voice just as I picked up the ’phone. It sounded as if someone was in the call-box with her and was forcing her to…’

The ’phone shrilled and Temple scooped it up with one quick movement.

‘Take it easy, Temple,’ Forbes cautioned.

Temple put a finger into his free ear. ‘Hello?’

‘Paul—’ Steve’s voice was a little stronger, but she was still tense.

‘Steve,’ Temple said, speaking slowly and deliberately but with all the urgency he could muster. ‘Where are you calling from?’

‘I don’t know the number.’

‘Darling,’ he told her very gently, ‘look at the dial.’

‘It’s a call-box.’

‘Well, where is it?’

‘Paul, I’m trying to concentrate,’ she was evidently dazed and confused, ‘but somehow I can’t—’

He asked: ‘Is there anyone with you?’

‘No. Not now, darling.’

‘Well,’ he tried again, still as if coaxing a frightened child, ‘where is the telephone box, Steve?’

‘It’s at Euston. Just inside the station.’ She was near to tears and her voice was beginning to break. ‘Please come and fetch me, darling. I’ll wait for you in the station near the bookstall.’

‘I’ll be there in ten minutes!’ This time Temple rammed the receiver down on the cradle. His face was grey as he turned to Forbes and Raine. ‘She’s at Euston Station.’

‘Right! Come on, Temple!’ Forbes was already heading for the front door. Raine started to follow, but the older man put a finger to stop him and nodded at the telephone.

‘Get through to the Yard. Warn all cars in the area but tell them to stay clear of the station. Follow as soon as you can. We’ll see you at Euston.’

Knowing that Raine would have no problem with transport, Forbes commandeered the police car waiting down in Eaton Square. The superintendent had chosen as his personal driver a young constable who had passed out of the Police Driving School at Hendon with a Class A. Authorised to use the blue light and siren he made his tyres squeal as he careered round Belgrave Square. The carousel of traffic at Hyde Park Corner yielded to the white police Rover as it squirmed between taxis, buses and private cars. On the Hyde Park ring road they touched a hundred miles an hour and the houses along Park Lane flashed past in a blur. An obstinate Daimler limousine blocked them for a long ten seconds at Marble Arch and received a horn-blasting that sent him rabbiting on to the pavement. As the Rover sped along the Marylebone Road, Forbes and Temple were thrown from side to side when their driver swerved round the slow-moving vehicles, sometimes cutting boldly across to the wrong side of the road and forcing the oncoming traffic to give way to him.

A quarter of a mile from Euston Forbes called out: ‘Cut the siren now, Newton.’

Temple glanced at his watch. He had automatically checked the time of Steve’s call. It looked as if he was going to keep his promise of being at the station within ten minutes. As if in confirmation the clock of the church across the road began to chime the quarters. Raine’s driver braked and swung in through the entrance reserved for buses, slowing behind a Number 14 as it circled the memorial to London and North Eastern Railway personnel killed in the 1914–18 war. Temple, all his senses at full stretch, noted the four statuesque figures guarding it, heads bent over, hands folded on their reversed rifles – an attitude of permanent mourning.

‘Well done,’ Forbes told the driver, as he deposited them at the kerb. ‘Wait for us here.’

Outpacing the passengers who had alighted from the bus, Forbes and Temple hurried across the broad, almost deserted forecourt, past the statue of Robert Stephenson and through the glass doors into the main hall. Both men were wary and watchful. There seemed no good reason why Steve should be kidnapped and then released after only five hours without some sort of pay-off. She could still be in grave danger. At this time of night the bookshop at the east side of the main hall was closed and only a lone vendor of newspapers was doing business.

Temple shook his head. ‘She’s not here.’

The loudspeakers boomed out some announcement about a train shortly due to depart for Edinburgh. The panels on the indicator-board flapped as a new set of departure times was rung up. From one of the platforms a posse of travellers just in from the North spilled out, dazedly lugging suitcases.

‘Is there another bookstall?’ Forbes was turning his head this way and that, searching for a slim woman in a blue suit. Charlie had told them what Steve was wearing when she’d set off for the airport.

‘There may be.’ Temple had started across the spacious hall, his eyes checking the entrances to the bars, restaurants, information desks. People were still crowding up and down the moving staircases leading to the Underground. Half a dozen skinheads were sitting disconsolately in front of the marble plaque commemorating the opening of the new station by Queen Elizabeth II on 14 October 1968. But no sign of Steve.

He stared at the flower-sellers packing up what was left of their stock. The bunches of spring daffodils reminded him vividly of her. So often he had bought her a huge bunch on his way home. Then suddenly, he knew what had happened.

‘Sir Graham, you wait here. It’s just a thought, but—’

Temple quickly located the sign pointing to the ladies cloakroom. Dazed and scared as she was, Steve would still have been thinking about her appearance. It would be just like her to believe she had time for a quick check-up in front of a mirror. He had entered the opening of the passageway that led to the toilets and was bracing himself to invade the women’s domain when he saw a figure in a blue suit coming out through the door. Three seconds later they were in each other’s arms.

‘Steve!’

‘Paul!’

She was almost sobbing with relief. He held her away from him for a moment.

‘Darling, you said by the bookstall.’

‘Yes, I know. But I knew my face looked awful and I never thought you’d get here so quickly.’

‘Well—’ Temple let out a long sigh. ‘Thank God we’ve found you.’

Forbes had come striding over from the flower stall. ‘Are you all right, Steve?’

‘Yes, Sir Graham.’ Steve managed a little smile. ‘I’m just – a little tired, that’s all.’

‘What happened?’ Temple asked. ‘How did you come to be here? Who was that man whose voice I heard?’

‘Paul, I’m confused…and frightened…I hardly know…’

‘Wait a moment, Temple,’ Forbes said in a low voice, his eyes on Steve’s trembling hands and nervously restless glance. ‘I think we’d better get her home and let a doctor see her before we start asking too many questions.’

‘You know, Temple, this really is an extraordinary affair.’ Sir Graham Forbes put the glass of whisky Temple had given him on the table beside his chair. ‘I’ve never come across a case quite like it before. No ransom – no mysterious notes – no threats – no blackmail. Nothing.’

‘And no motive either, sir,’ added Raine, who had opted for a glass of lager, ‘so far as we can see.’

The hands of the clock on the mantelpiece of the Temples’ sitting-room had moved round to twenty past eleven. More soberly than on the outward journey Raine’s driver had brought Steve, Forbes and Temple back to Eaton Square. Temple had been lucky to find the partner of their own doctor at home and he had come round at once. The three men were having a drink while they waited for him to pronounce her fit for questioning.

‘They must have had a motive!’ Temple exclaimed. He was pacing restlessly up and down the room. ‘Whoever they are, they must have had a reason for picking Steve up like that!’

‘I agree, Temple. But what was the reason? After all, it isn’t as if you’re mixed up in a case at the moment, or even helping us over…’

Forbes was interrupted by the door opening. Dr McCarthy put his head round it. ‘May I come in?’

He was a small, competent but slightly self-effacing man with a balding head and prominent ears. He wore rimless glasses and carried the regulation leather bag.

‘Yes, of course, Doctor. What’s the verdict?’

‘Nothing to worry about – nothing at all.’ The doctor ventured a little further into the room. ‘But there’s no doubt Mrs Temple has had quite a shock, and, in my opinion, she’s either been drugged or even possibly hypnotised.’

‘Hypnotised!’ Temple echoed incredulously.

‘However, the main thing is, there’s nothing for you to worry about, Mr Temple. What your wife needs now is rest, and plenty of it! I’ve given her a sedative; she’ll probably sleep most of tomorrow morning.’

‘Thank you, Doctor.’

‘I’ll look in during the afternoon, or give you a ring tomorrow evening.’

‘Thank you,’ Temple said again, and moved towards the door to see him out.

But Dr McCarthy had picked up the purposeful and expectant atmosphere in the room. He peered sternly at Raine through his small lenses. ‘And, Superintendent…’

‘Yes, Doctor?’

‘My patient can’t answer any questions – not at the moment, at any rate.’

Raine nodded, accepting the ban with resignation. ‘Very well, Doctor.’

‘So hold your horses until tomorrow.’ McCarthy turned to Temple, who was standing waiting by the door. ‘And that goes for you too, Mr Temple.’

When Steve woke she did not immediately open her eyes, afraid that she might see again the walls of the small room where she had been held prisoner. But the sound of music was reassuring and she dared to raise her eyelids. With relief she saw that she was in her own bedroom. Though it was darkened she could identify the familiar objects of everyday life.

‘Paul…What are you doing sitting over there?’

‘I’m listening to the radio and watching you, darling.’

‘Well, what time is it?’

‘What time do you think?’ Temple asked, smiling.

‘Oh, I don’t know.’ Steve sat up in bed, stretched her arms and yawned. ‘The sun’s shining so it must be morning.’

‘It’s a quarter past five.’

‘A quarter past five? In the afternoon?’

‘Yes, darling. You’ve had quite a nice little nap.’

‘How long have I actually been…?’

‘Since eleven o’clock last night.’ Temple put the paper down and came over to the bed. ‘The doctor gave you a sedative.’

‘Good heavens! You shouldn’t have let me sleep like this! Oh, Paul – you look wonderful! How lovely to see you again!’ She reached out towards him as he bent down to kiss her. ‘Did you have a nice trip?’

‘Yes, I did. But it’s the last trip I’m making without you, Steve.’

‘You can say that again!’ She laughed and slid luxuriously back under the bedclothes. There was more colour in her cheeks than the night before but she had dark shadows under her eyes.

‘How do you feel?’

‘I’m perfectly all right now. There’s no need to look so anxious.’

He sat down on the edge of the bed. She put out a hand to grasp his. ‘Do you feel well enough to talk?’

‘Yes, of course.’

‘What happened yesterday, Steve?’

‘Well, now – let me think…’ Her eyes clouded as she stared at the half-drawn curtains. ‘I’m not sure where to begin…’

‘Suppose we begin at the very beginning. You set out to meet me at the airport, just as you planned…’

‘Yes, that’s right. I arrived there with plenty of time to spare, and parked the car. A man in uniform, one of the airport officials, came up to me. He checked the number of my car, and asked if I was Mrs Temple. He told me your plane had arrived ahead of schedule and you were waiting for me in the Concorde Lounge.’

‘Would you recognise this man again?’

‘I doubt it.’ She shook her head. ‘He asked me to follow him to another car just outside the car park. I thought he was taking me to another building some distance away. In the back of the car was a woman wearing air hostess’s uniform. I sat beside her and the man climbed into the driving seat and we drove off. We’d been going for about a minute when the woman suddenly pushed a pad over my face and I felt a jab in my right arm. I’m afraid I don’t remember anything else – about the journey, I mean. When I came to I was in a darkened room. I felt absolutely awful. Everything was going round and I wanted to be sick. After a while a man came into the room and gave me a drink. I don’t know what it was, but it certainly made me feel better.’

‘Was this man the phoney airport official?’

‘I couldn’t see him very well, but I don’t think he was. For one thing, his voice sounded different.’

‘And what did he say?’

‘He said there was nothing to worry about – that I wasn’t in any danger and later on they’d be releasing me.’

‘Did you ask why they’d kidnapped you?’

‘Yes, and he said: “We did it as a warning, and to prove that it was possible, Mrs Temple.” ’

She felt his grip on her hand tighten, saw the line of his mouth harden.

‘Go on, Steve.’

‘Well, I was left alone for ages after that. It must have been two or three hours later before another man came into the room. I think this was the man at the airport; he was about the same height and he sounded rather like him.’

‘But you’re not sure?’ he said sharply.

‘No, Paul, I can’t be a hundred per cent sure. Anyway, this man also assured me that there was nothing to worry about and that they were going to send me home. About half an hour later they drove me down to Euston and allowed me to make the telephone call.’

‘But didn’t they give you any idea what this was all about – why they’d abducted you?’

‘Not the slightest. Don’t you know, Paul?’

‘I haven’t a clue. I’m not investigating a case at the moment. I’m not mixed up in anything – you know that, Steve.’

‘If only I could remember more details…What the people looked like…’

‘Don’t worry about it, darling.’ He released her hand and stood up. ‘You’re all right, that’s the main thing.’

‘Yes, well – you must have been pretty worried.’

‘Oh, not really, darling.’ He kept his expression dead-pan. ‘I just went berserk.’

Steve laughed, watching him affectionately as he moved towards the hanging cupboard that filled one whole wall.

‘By the way, I put your new coat in the wardrobe.’

‘My coat?’

‘Yes. We found it in the back of the car when we collected it from the airport.’

‘But I didn’t take a coat with me,’ Steve said, puzzled.

‘Yes, you did, darling. Here it is.’ Temple slid the white door back on its runners, reached inside and took out an overcoat on a hanger.

He held the coat up for her to see. It was in classic style, of fawn cashmere, with a tie-belt and sleeves trimmed with leather buttons. What surprised him was the weight of the material.

‘That’s not my coat!’ Steve exclaimed.

‘But it is, Steve! It was in the back of your—’

‘I don’t care where it was! It’s not my coat!’

Temple found it hard to understand why she was so vehement in repudiating this fashionable garment.

‘Are you sure, dear?’

‘I’m positive!’ More quietly she asked: ‘Is there anything in the pockets?’

He carefully checked both pockets. ‘No, nothing.’

Steve pointed a finger towards the top of the coat. ‘There should be a maker’s name on the back of the collar somewhere.’

‘Yes, I’m just looking for it.’ Temple took the coat off the hanger and looked inside the collar. ‘Ah, here we are!’

He turned the label towards the light to read the name. ‘Margo…’

Superintendent Raine took his mackintosh off and handed it to Charlie, who hung it up in the little cloakroom. Through the closed door of the sitting-room he could hear someone playing the piano – one of Chopin’s Nocturnes. Despite his air of businesslike efficiency Raine was a sensitive man and a lover of music. From the style of the playing he was able to recognise a woman’s touch.

The music stopped when Charlie knocked on the door and went in to announce the visitor. A moment later Temple himself appeared.

‘Hello, Superintendent!’ he welcomed Raine warmly. ‘Come along in!’

The Temples’ coffee cups had been put back on the silver tray and a brandy glass was on the table beside Paul’s chair. The book he had been reading had been placed on the arm, with the cover uppermost. It was the novel that had recently won the Booker McConnell prize.

Steve had come out from behind the baby grand piano.

‘Good evening, Mrs Temple.’ Raine gave her a courtly bow. ‘You look better than you did a week ago.’

‘Yes,’ Steve smiled. ‘I’m fine now, thank you very much.’

‘I just happened to be passing and I thought I’d drop in and have a word with you.’

‘Glad to see you.’ Temple indicated a chair. ‘Sit down. Can I get you a drink?’

‘No, thank you. I’m afraid my day’s work is not done yet.’ Raine sat down, as usual leaning slightly forward. ‘Well, we don’t seem to have got very far during the past week. We’ve made enquiries about the coat, but we’ve drawn a blank. We’ve failed to find the owner, or even the shop where it was bought.’

‘What about the makers?’

‘We can’t even locate the makers. According to all accounts, there isn’t a coat firm called Margo – not in this country, at any rate.’

‘I see.’ Steve and Paul exchanged a glance. ‘Did you check with the airport people?’

‘Yes, and we’ve had no luck there either, I’m afraid. I suppose you haven’t had any bright ideas, Mr Temple?’

‘No, I’m afraid I haven’t, except that…Well, I think the people who kidnapped Steve were labouring under the delusion that I was just about to investigate a case of some kind.’

‘And you think the Mrs Temple incident was a warning to keep out?’

‘Yes, I do.’

‘Well, that’s a possible explanation, I suppose,’ Raine conceded dubiously. ‘But what’s the case?’

‘You tell me.’ Temple tapped his pipe out and reached for the tobacco jar. ‘I never interfere in anything without an invitation. What’s your biggest headache at the moment?’

‘Oh, our biggest headache is The Fence – trying to find out who the devil he is. But we’ve had that headache for some time now. I doubt whether we’ll ever solve it.’

Steve had gone back to the piano stool and was leafing through some sheet music, obviously intending not to intrude on the conversation; but she was drawn into it in spite of herself.

‘What do you mean – The Fence?’

‘Well, you know what a fence is, Mrs Temple?’ Raine had to shift his position to face her.

‘Yes – a man who receives stolen property.’

‘That’s right. Well, during the past twelve months there’s been several robberies. I mean, really big stuff. The two jewellers in Leicester Square…the fur warehouse in Bond Street…’

‘Lord Renton’s place in Eaton Square,’ Temple put in, as Raine hesitated.

‘Yes, that’s right. Well, it’s our opinion that these particular jobs were all done…’

‘…by the same gang!’ Steve supplied, determined not to be outdone.

Raine laughed good-humouredly. ‘No, Mrs Temple. Nothing quite as simple as that. We think – in fact, we know that the various jobs have been done by different people. We feel pretty confident, however, that the stolen property was, in every case, handled by the same person.’

‘The Fence?’

‘Yes, Mrs Temple. So far we’ve failed to find out who this fence is – or where he operates from. But sooner or later we’ve got to find him, because, at the moment, he’s indirectly responsible for a great many of the robberies in this country.’

‘Then I can see why you’ve got to find him,’ Temple remarked drily.

‘Still, we’ve no reason for thinking – no proof, as it were that Mrs Temple’s experience had anything to do with The Fence.’

‘No, Superintendent,’ Temple said thoughtfully. ‘No proof.’

There was a short silence, but Raine made no move to go. ‘There was one thing I wanted to ask you. The day Mrs Temple disappeared you said something about a note – a telephone message – which was on the pad by the side of the bed.’

‘Yes, of course!’ Temple struck his brow with the flat of his hand. ‘I forgot all about that! There was a note, Steve. It said: “Tell P. about L.”’

‘Oh, that was Laura Stafford,’ Steve said dismissively. ‘She telephoned one morning and said she wanted to see you. She seemed awfully disappointed when I said you were in New York.’

‘Who’s Laura Stafford?’ Temple enquired.

‘She’s a journalist – or rather she was several years ago.’ Steve forsook the piano stool and moved over to the sofa. ‘We used to see quite a bit of each other when I worked in Fleet Street. Then she left and married a man called Kelburn.’

‘Kelburn?’ Temple echoed, with surprise. ‘George Kelburn?’

‘Yes, I think so.’

‘Very wealthy. North country. She’s his second wife.’

‘That’s right.’ Steve leaned back and crossed her legs. Raine bent his head and dutifully studied his fingernails. ‘Anyway, when I said you were in New York she said she’d get in touch with you later. I thought nothing of it at the time, but a couple of days later I bumped into Laura in Freeman and Bentley’s and naturally, I mentioned the telephone call, and to my amazement she said she hadn’t ’phoned.’

Raine looked up sharply. ‘She said she hadn’t?’

‘That’s right, Superintendent. She said she certainly had no wish to consult Paul about anything.’ Steve turned to Temple, whose expression showed his scepticism. ‘Darling, why were you surprised when I mentioned the name Kelburn?’

‘Well, coming over on the ’plane a man called Langdon introduced himself to me. He works for George Kelburn. Apparently Kelburn’s having trouble with his daughter and he’s asked Langdon to try and sort it out.’

‘Yes, I’ve heard of Miss Kelburn,’ Raine said meaningfully. ‘Julia, by name.’

‘That’s right.’

‘Always in the newspapers. She must be quite a handful, that young lady. I don’t envy Mr Langdon his assignment.’ He put his hands on his knees to push himself upright. ‘Well, I’ll be making a move. Glad you’re feeling better, Mrs Temple.’

Raine had been gone for an hour and Steve had announced her intention of going to bed early when the doorbell rang and they heard Charlie going to answer it. A few moments later his head came round the door.

‘What is it, Charlie?’

‘Are you in or out, Mr Temple?’

‘At a quick glance, I should say we’re in.’

‘Well, there’s a Mr Langdon would like to see you. Looks like a Yank to me.’

‘Yes – he is a Yank, as you so elegantly put it, Charlie. Show the gentleman in.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Langdon?’ Steve asked. ‘Is this the man you met on the ’plane?’

‘Yes.’

‘Did you ask him to call?’

‘Not in so many words, but I said if I could be of use any time I’d be pleased to see him.’

Like Raine, Langdon refused the offer of a drink, but accepted a chair. Steve resigned herself to being a listener to another of Temple’s interviews. She always admired his capacity for making people feel that a visit from them was just what he had been hoping for and that he had all the time in the world to listen to their confidences.

‘I’ve already had more than my share of drink this evening,’ Langdon said with a sigh. ‘Which isn’t surprising – considering.’

‘Why, is the Kelburn business getting you down?’

‘It certainly is.’

‘You’ve seen Julia, I take it?’

‘Yes, half a dozen times. It’s hopeless – she has every intention of doing precisely what she wants.’

‘And what about the young man she’s keen on – Tony Wyman?’

‘I went to see Wyman last night.’ An expression of distaste crossed Langdon’s face. ‘At The Hide and Seek. He completely denied that he and Julia were engaged. He just laughed when I said that Kelburn would pay him twenty-five grand not to see her again. He became quite offensive. Said he wouldn’t marry the girl if she was the last piece on earth. So far as he was concerned Kelburn could keep his twenty-five grand and his daughter too!’ Langdon sighed again.

‘What a charming young man!’

‘You can say that again, Mrs Temple. I wasn’t exactly enthralled by Master Wyman!’

‘Do you think he was telling the truth?’

‘I don’t know, Temple. He sounded convincing and yet it just doesn’t add up. Everyone I’ve spoken to swears he’s got his eye on her. Temple, I know this is a bit of a cheek, but do you think you could make one or two enquiries for me?’

Steve shot Temple a warning look, but he seemed to be more interested in refilling his pipe.

‘All right, Langdon, we’ll get on the grapevine and see what we can do.’

‘That’s mighty kind of you,’ Langdon said effusively. ‘I appreciate it, I really do.’

‘Then how about changing your mind and having a drink?’

As Steve turned away to hide her exasperation at Temple’s excessive hospitality, Langdon put his head on one side. ‘There’s nothing I’d like better.’

Temple raised his head from the pillow at the third ring of the telephone, but no sooner was he properly awake than it stopped.

‘Probably realised they were dialling the wrong number,’ Steve said beside him. He could tell from her voice that she had been lying awake.

‘What time is it?’

‘Struck three a few minutes ago.’

‘Couldn’t you get to sleep?’

‘I keep thinking of Laura Kelburn. It must be awful having a daughter like Julia. Paul, do you think she was lying when she said she hadn’t telephoned me?’

‘I can’t see why she—’ Paul stopped as the ’phone started ringing again.’ Who could be telephoning us at this hour?’

‘Take your time, Paul. If they really want us they won’t ring off.’

Temple waited for a little while before switching the light on and picking up the ’phone.

‘Hello.’

‘Is that Paul Temple?’ A woman’s voice, speaking softly, as if she was afraid of being overheard.

‘Yes, speaking.’

‘This is Mrs Kelburn…’ There was a crackling on the line and he could hardly catch the name.

‘Who?’

‘Mrs Kelburn…Laura Kelburn…’

‘Oh, good evening – er – good morning, Mrs Kelburn.’

‘Mr Temple, I’m sorry to disturb you at this time of night, but – I’ve got to see you.’ There was desperation in her voice as she added: ‘It really is important.’

‘Well – what is it you want to see me about?’

‘About – about Julia. My stepdaughter.’

‘What about Julia?’ Temple asked, not trying very hard to conceal his impatience.

‘When can I see you, Mr Temple?’ She was still speaking so softly that he could hardly hear her. ‘Will nine o’clock be all right? I’ve got your address so…’

‘Look, Mrs Kelburn, I’m quite prepared to see you, but first of all I must know what this is all about.’

‘I’ve told you. It’s about my stepdaughter – Julia.’

‘Yes, I know, but what about Julia?’

There was a long pause, but no indication that she had rung off. Temple wondered whether someone had taken the receiver from her. Then suddenly she said very quickly but quite distinctly: ‘She’s going to be murdered.’

There came a click and Temple was left listening to the dialling tone.

‘Hello, Steve!’ Temple had finished his toast and marmalade and was pouring himself a second cup of coffee before his wife appeared for breakfast the next morning. ‘You’re nice and late this morning!’

‘Yes, I know,’ Steve admitted wryly. ‘I didn’t get to sleep until five o’clock.’

‘It’s not surprising. We didn’t stop talking until half past four. I’ll pour you some coffee.’

‘No, I don’t want any coffee, dear. I’ll just have the orange juice. What time is it, anyway?’

‘Twenty past nine.’

‘My word, we are late…’

‘Yes – and so’s your friend, Laura Kelburn. She said she’d be here by…‘He was stopped by a long peal on the doorbell. ‘This will be her now.’

‘Do you want me to stay?’

‘Yes, of course.’

Temple had time to pour an orange juice and put it down at Steve’s side of the table before Charlie opened the door.

‘Superintendent Raine would like to—’ Charlie broke off scandalised as the Superintendent pushed in past him. He had not even taken time to remove his overcoat.

‘Excuse me! Mr Temple, may I have a word with you?’

‘Yes, of course. All right, Charlie.’ Temple dismissed Charlie with a reassuring nod. ‘What is it, Raine? What’s happened?’

‘We picked a girl out of the river – about two hours ago. She’d been strangled. It was George Kelburn’s daughter.’

‘Julia Kelburn?’

‘Yes. But that isn’t everything.’ Raine paused for a moment. ‘The dead girl was wearing a coat. There was a name label stitched inside the collar. We’ve seen that name before, sir.’

Temple nodded. He was already ahead of Raine.

‘Margo?’