Читать книгу With Scott Before The Mast - Francis H. Davies - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter I. Signing on

For over nine years from first to last, I served in expedition ships engaged in exploration and scientific research in the Antarctic.

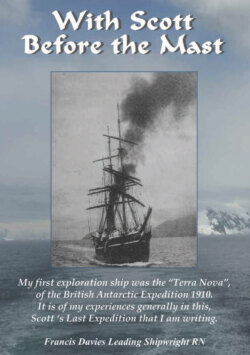

My first ship was Terra Nova of the British Antarctic Expedition 1910 – Scott’s Last Expedition, and it is of my experiences, generally, in this expedition that I am writing. Looking back, I now see it was the end of an era in Antarctica or more correctly perhaps, of Polar exploration when the work was carried on in wooden sailing ships of great strength, especially constructed to withstand ice pressure, and with auxiliary steam power for working through the heavy ice-floes. The vessels were built for whaling and sealing in the Polar Regions, and were the pride of the Dundee shipbuilders during the latter half of the last century.

My association with exploration started in the spring of 1910 when I was serving as a shipwright in HMS Vanguard, Super-Dreadnought, recently commissioned for the first time. One day, whilst my mate and I were in the dockyard at Devonport scrounging material for a particular job we had in hand, he met one of his old shipmates who during a ‘quack’ about old times, mentioned he had heard that three shipwrights were required as volunteers for an expedition to the Antarctic, to be led by Captain Scott. I immediately cocked up my ears and from a few apparently disinterested remarks, I gathered that the carpenter who had served with Captain Scott on his previous expedition, and was now a Shipwright Officer RN, was on the look out for suitable volunteers.

As I pondered on this casual information, memory of my boyhood’s favourite book Nansen’s Farthest North came vividly back. I remembered how I had longed for similar adventure. I lost no time getting in touch with the officer mentioned, who was then holding an appointment in the Shipwright Officer’s drawing office, nearby.

Within the hour I had had an interview and started the ball rolling. As he didn’t know me personally he said he would contact the Shipwright Officers under whom I had served and, if everything was satisfactory he would let me know in a day or two. I was not bothered about my professional qualifications, I did not see any difficulty in that direction, but I doubted whether my ten stone four pounds measured up to what I imagined an Antarctic explorer should be.

Two days later the Shipwright Officer came to see me on board Vanguard, and told me that from the reports he had already received, I was undoubtedly the man for the job and that he had forwarded my name to Captain Scott with a strong recommendation.

I was now on the tiptoe of expectation. In a few days I received a letter from Captain Scott, informing me that I had been accepted and that application had been made to the Admiralty for approval. As the days passed and there was no reply from the Admiralty, I became unduly anxious, particularly as Vanguard was due to sail for Bantry Bay on the west coast of Ireland, to calibrate her guns. I was afraid this might prejudice my chances.

Sailing day arrived and still there was no news.

However, after we had been a few days at Bantry Bay, I received a note by messenger from a friend of mine, a writer in the captain’s office, telling me confidentially that my Antarctic job had been approved by the Admiralty and that I was to be discharged forthwith, also that efforts were under way to prevent my leaving the ship before she returned to Devonport.

With this information up my sleeve I went aft to the Captain’s office to enquire of the paymaster in charge if there was any news concerning my release by the Admiralty for service with the expedition. He told me there was, and asked if there was any immediate hurry.

To be forewarned is to be forearmed. I said there was certainly need for haste, and pointed out that the expedition was due to sail from London in a months time, and meanwhile there was the refitting the ship, the huts for Winter Quarters, stores and a hundred and one things to be seen to.

I asked him to take me before the Commander, a very keen gunnery expert who was then on Monkey Island (upper bridge) directing calibrating operations. The commander was not easily approachable at the best of times so I was not surprised when the paymaster hesitated to butt in just then. However, he eventually agreed to take me before the Commander and up we climbed to Monkey Island.

It was as I had expected, when the paymaster tried to explain the purpose of my visit the Commander went off the deep end, saying he could not attend to the matter then and in any case there was no boat available to land me. I sensed he was intending to be awkward but I was not to be fobbed off in this manner and told him if there was any difficulty in my getting off the ship I should have to wire Captain Scott. That tore it! He was furious and literally swept us off the bridge.

This little set back did not deter me from making arrangements to leave the ship at short notice, so when later, the Commander sent a message to the effect that he would give me ten minutes to get out of the ship I had time to spare. The boat landed me at Glengariff, not far from where the ship lay, some fourteen miles from the town of Bantry, the terminus of the railway in that direction. It would have been possible to land at Bantry, had a boat been available, but I considered myself fortunate to be landed at all under the circumstances.

My first concern was to obtain transport for myself and three hundred weight of luggage, motor transport was not in general use and practically unknown in this out of the way place. I was fortunate in finding the driver of a jaunting car, who was going to Bantry later in the afternoon to meet some visitors arriving by train.

He said he thought it was a bit of a load for his horse, I thought so too when I saw the horse which appeared to be built on the lines of a greyhound, but under the mellowing influence of a couple of pints of good Irish porter, for which that part of the country was famous, we came to terms.

Whilst waiting I celebrated my good luck so far, and by the time we started for Bantry I was full of the joys of Spring. As the old horse clip-clopped along the hard, dusty road I could see Vanguard still engaged on her lawful occasion. At intervals one of her big guns answered the questions with a flash and a roar, then all was peace again as the smoke drifted slowly away and disappeared in the haze. What a picture she made! Britain’s latest battleship, - the finest in the world – on that lovely afternoon, riding on the calm waters of the Bay.

In such a setting who would have been bold enough to prophesy that within little more that four years our country would be at war and fighting for very existence, and that during the war I should see the fine ship destroyed in the matter of minutes with most of her gallant crew. I never saw any of my messmates again. After completing a two year commission in the ship, most of them were drafted to HMS Monmouth, one of the ships of Admiral Craddock’s Squadron sunk by the Germans at the battle of Coronel, 1914. Many years later, when serving in a small scientific research vessel during survey of the Humboldt Current, off the coast of Chile and Peru, the ship was stopped about the position of the battle of Coronel, to pay our respects to the gallant dead.

I arrived at the Royal Naval Barracks, Devonport, on 1 May, and was discharged the following day for service with the British Antarctic Expedition, with instruction to report to Captain Scott, at the offices of the expedition, Victoria Street, London. In spite of the fact that I had volunteered for this job I was escorted to Plymouth by a petty officer who saw me safely on the train, complete with travelling warrant and meal ticket, the Navy never does things by halves.

At Exeter I decided to cash in on my meal ticket at a refreshment buffet on the station. It entitled me, beside sandwiches to a pint of beer. I shall never forget that beer, it was awful just swipes.

On arrival in London I put up at the Union Jack Club in Waterloo Road, which was run exclusively for the services, Navy and Army. The Royal Air Force was not even a dream then, flying being in its infancy. As a matter of fact, Bleriot had recently flown the channel and this was considered a great feat. The club was a boon to servicemen it had all the amenities of a good class hotel with excellent service at modern charges, which I deeply appreciated as I did not know London, having only been there once before on a visit to the White City exhibition.

On my first evening I took a stroll to get my bearings, and coming upon Drury Lane Theatre, where the play ‘The Whip’ was then running, I took the opportunity of seeing it whilst the going was good and enjoyed it very much.

Francis Davies' shipwright's trunk.

Francis Davies and family, wife Ethel, daughter Beatrice (Maidie), and son Peter.

Captain Robert Falcon Scott CVC RN