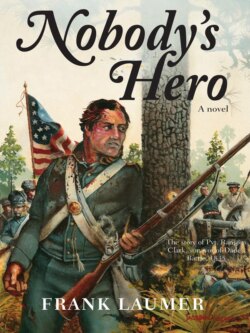

Читать книгу Nobody's Hero - Frank Laumer - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

Ransom Clark looked toward the sun struggling up through the tall longleaf yellow pines on his right, burning away the showers of the night. Coming on eight o’clock, he figured, temperature about fifty degrees. It was the 28th of December, 1835. Six months to go, then I’m goin’ back. He held the thought. Six months. Lucy. His mouth widened slightly, his eyelids compressed in a small tight smile, the tips of perfect teeth a quick white streak on his grizzled, swarthy face. The overcast sky was silver-gray but clearing. The pine bark, flaking like rust, was rose colored in the early light; the green needles glittered.

He was second man from the lead in the right file of the column of eighty-six enlisted men with fourteen non-coms and eight officers commanded by Brevet Major Francis Langhorne Dade. Born in Virginia, now forty-three years old, Dade had boasted that he could march through the Seminole Nation with a sergeant’s guard. He was married and had a daughter, Fannie Langhorne, who would be five years old next month. Amanda and Fannie would be waiting for him back in their comfortable frame home on Palafox Street in Pensacola. The detachment was in march from Fort Brooke at Tampa Bay north one hundred miles to Fort King. They were in double file, column of route, four feet between the files and between each man and the man that followed. Clark caught glimpses of the advance guard a hundred feet ahead, a shield to blunt attack, a sergeant and five men on foot led by 2nd Lt. Robert Richard Mudge, twenty-five, West Point class of 1833, the oldest of eleven children of Benjamin and Abigail Mudge of Lynn, Massachusetts. Nearer, between the main column and the advance, Captain Upton Sinclair Fraser was on horseback. In New York in June 1814, twenty years old, he had been appointed an ensign in the 15th Regiment of Infantry. Now he was forty-one, in command of Company C, Third Artillery. Fraser was known as “the soldier’s friend,” not a common trait among officers. In addition, he had openly remonstrated with the major several times on behalf of the interpreter, Luis Pacheco, a slave, who walked now beside Fraser’s horse, his left hand on the stirrup.

The long blue column—from the advance guard back to the main body, followed by the horse-drawn cannon, three oxen hitched to the wagon, and finally the rear guard—was some five hundred feet long. They had been up before dawn, on the road nearly two hours. A good fifty miles out of Fort Brooke, a little less than fifty miles to go. They had been slowed by four river crossings and it had taken five days to make it this far, but there were no more rivers, only high ground and open country ahead. Ought to make it in to Fort King, safety, in two, three more days.

A cool west breeze rustled the high palmetto fronds on both sides of the twenty-foot-wide Fort King Road with a click and a rattle. The road had been cleared by the army ten years before through the wilderness of pine barrens, swamps, and forests that made up the Florida Territory, the slash of a sword through the heart of the Seminole Nation. This is more than a sergeant’s guard, Clark comforted himself, this is a small army: two full companies of regulars under the command of eight officers, five of them West Pointers. The men were armed with muskets, a few swords and pistols, and backed up by the cannon.

Finally out of the swamps, the land was rising, opening out from the heavy underbrush of the river valleys to a pine barren, fallen needles blanketing the ground, smothering all growth except palmetto and thin, brown winter grass. It was common knowledge that Indians were like cutpurses, catching you in the dark and ugly places, taking you by surprise. Damn fools if they didn’t, Clark thought. He’d heard that of the five thousand Seminoles in the whole territory, no more than fifteen hundred were warriors. They didn’t have organization, command, a cannon, neither the time nor the weapons to make real war. They relied on stealth.

It had begun the second night, the Big Hillsborough, Saunders store, burnt to the ground, flames still playing across the water from the remains of the bridge built just last year. The major had taken every precaution, the command drawn together every night within a barricade three or four logs high thrown up to slow an attack, half a dozen sentinels posted on a relief one hundred yards and more outside and around. They had heard movement, shouts, screams like a cut pig, a few shots fired, a reminder that the Seminoles had good Deringer rifles with better range and more accuracy than the army’s muskets. Men had been tense, jumping at every sound. They had stared at one another around their fires, checked and rechecked their weapons. “What’re they sayin’, Clark? Are they gonna ’tack?” He shook off the questions. “Nah. Just threats, braggin’.” What use to translate the messages—rage, hate, “We’ll kill you all.”

The babble of voices around him reminded him that only half of the enlisted men of the command were American born. They had come from ten of the twenty-four states, most of them along the Atlantic seaboard from Maine to North Carolina, with a dozen men from Pennsylvania, four from Vermont. And while most of the slave hunters—and settlers—pushing into Florida, clashing with the Seminoles, stirring up trouble, were from Georgia and Alabama, Clark had noticed that no volunteer from either state was in the ranks. He’d heard that recruiters didn’t spend much time in the slave states; wasn’t worth the effort. The greatest source for recruits was laborers and immigrants—where slaves provided most of the labor, there were few white laborers and immigrants were not welcome. He knew that some recruiters preferred native-born Americans; others had found they were more difficult to discipline than foreigners, were not accustomed to military subordination, were less patient and plodding.

Of the foreign-born around him a third were Irish, the rest from Scotland, England, Prussia, Germany, Canada, and God knew where else. Their voices were a medley, a babble of dialects and languages. He recognized other Yankees with their “I reckon so”; Southern Crackers with their nasal twang; Germans spluttering in high and low Dutch; lots of Irish, swearing by the Holy Spoon and all the patron saints; Scotch who praised the land o’ cakes; with here and there a John Bull. And while the army refused to accept branded deserters from its own ranks, it was well known that of the two thousand enlisted men of the British army stationed in Canada who had deserted last year, fully a third were serving again, this time in the American army. For foreigners, Clark figured, it was a chance to learn the language and get food, clothing, shelter, and six dollars a month while they did it. For Americans it was probably the handiest way to escape troubles, romantic, financial, or legal. ’Course, some of the younger ones were just looking for adventure.

Short and tall, young and old, domestic and foreign, it seemed like most of the fellows he’d got to know had come into the army as common laborers with no claim to any special skill, trade, or profession. He had heard such men referred to as typical of the “rag-tag-and-bobtail herd found in the ranks of the regular army; either the scum of the older states or of the worthless German, English, and Irish immigrants.” But he had also found among the men of Dade’s command tailors, clerks, printers, farmers, hatters, barbers, spinners, plasterers, blacksmiths, musicians, glaziers, painters, papermakers, shoemakers, watermen, a lampmaker, a couple of sailors, a weaver, tanner, carpenter, baker, hairdresser, even a teacher.

Still, it was true that most of them were simply laborers, illiterate, ignorant of their own ignorance—boys who had left the farm or small town and joined up in a confusion of boredom and patriotism, or older men who had failed at everything else and had settled for three squares a day and a flop. Clark’s own recruiting officer, more honest than most, had tried to discourage him with the warning “If you take this step you will regret it only once, and that will be from the time you become acquainted with your position until the time you leave it.”

Well, maybe so for some fellows, thought Clark, but not me. I can read and write. I got skills. I can plant and hoe, do a little blacksmithing, carpentry, work with horses. In the army I’ve traveled, met all kinds of people, put by a little money. Soldiering isn’t easy, but I’ve held, learned to handle myself. Six months and I’m done. I’m gonna see it through, I’m goin’ back to Lucy, I’m gonna live. Eunice Luceba French had become his talisman, his hope, his future. Before her there was nothing. With her he would learn, build, have a life. He knew it might only be a dream, but it was the dream that had helped him survive, helped him live.

While the column was orderly, route step allowed the men a certain leeway in their movement, swinging along, maintaining a loose order side to side, front to back, some silent, moody, others talking whether anyone listened or not. Time was, he reflected, when he would have paid no more attention to the men around him than was necessary for survival, would not have joined them in talk, given or received a greeting. Until Lucy he had not known the meaning of friendship, had had no concern for others nor reason to believe they would have any concern for him. Old Benjamin had taught him only to work and to curse. Now he knew an interest in others, felt a rough affection even for DeCourcy, Wilson, the rest. He looked around now, watching, listening. Some men marched straight and tall, others with rounded shoulders shuffled like they were still pulling the plow. Remembering the barren early years, he felt a wince of affection. Good men, he thought, most of them, sturdy, steady. He suddenly realized he was proud to be with them, a part of this command.

And while only three of the American enlisted men were from the South, five of the eight officers were Southerners; Major Dade from Virginia and 1st Lt. William Elon Basinger from Savannah, Georgia, twenty-nine, West Point class of 1830, whose wife waited for him back at Fort Brooke. He had assured her that he would be back to her “in a couple of weeks at the furthest.” Richard Henderson was from Jackson, Tennessee, a brevet second lieutenant, nineteen years old, class of 1835, classmate of John Low Keais, also a brevet second lieutenant, an orphan from Washington, North Carolina. And Assist. Surgeon John Slade Gatlin, twenty-nine years old, was from Kinston, North Carolina. At Fort Brooke Dr. Nourse had offered to trade places with him if he could be provided with a horse but none could be found. Now Gatlin was on foot with the men.

Capt. George Washington Gardiner, commanding Company C, 2nd Regiment of Artillery, from Washington, D.C., was forty-two, had graduated first in his West Point class of 1814. His wife, very ill, was in Key West with their two children. Fraser was from New York and Mudge from Massachusetts. Of the entire command, only Luis Pacheco had been born in Florida.

Along with the other men Clark wore the standard-issue black leather forage cap, seven inches high in front and back. It added to his height but nothing to his safety. In a pinch it could double as a bucket for water or grain. Like all artillerymen’s hats, Clark’s carried a brass A above the bill, Dade’s eleven infantrymen a silver I. His gray-blue overcoat was single breasted, woolen, lined with white serge with a standup collar and a cape. In the mild Florida winter it was hot on a march, heavy when wet. Running from collar to hem, seven inches above the knee, was a single row of nine gilt buttons. The thin, sharp edges could cut a man’s fingers if he was in a hurry, pressed too hard. Clark and a few others had rolled the coats, damp with rain, along with their five by six and a half foot, four-pound blue woolen blankets, tied them on the top of the black leather knapsacks carried high on their shoulders.

Clark’s knapsack cover had yellow painted crossed cannons for artillery. The one and a half inch number 2 above the emblem indicated his regiment, the letter C below, company. He wore a short sky blue jacket, collar edged with red, shoulder straps with pads and half fringe.

Under his jacket his long-sleeved white cotton shirt was already soaked with sweat, sticking to his skin. His woolen trousers, still damp and heavy from the last river crossing yesterday afternoon, matched the blue jacket, were held up by white cloth suspenders. The wide front flap of the trousers was secured with seven buttons, eleven if you counted those holding the suspenders. Not too handy when a fellow had a serious call of nature, was caught with his pants down.

His leather boots were short and black, with leather laces. No matter how many miles he walked, the soles were still smooth and stiff as an oak plank. With his right hand he reached up, readjusted the two white leather straps, worn and dirty, that crisscrossed his chest. Regulations now forbade cleaning them with white lead, claiming it had been found “injurious to health.” Not as injurious as the lead of a Seminole bullet, he thought.

One strap supported a bayonet in a leather sleeve that rode behind his left hip, the sixteen-inch-long triangular blade designed for stabbing, pointed but not sharp. The second strap carried a leather-cased wooden box on his right hip, bored to hold twenty-six cartridges under an ornamented leather flap, another twenty-four in a metal tray below. The straps were secured with a round brass clasp surmounted by a spread eagle that rested over his heart.

Beneath his cartridge box hung a canvas forage bag holding his ration issue: eighteen ounces of stale hard bread called “ship’s biscuit,” said to be healthier than fresh, along with a chunk of hard cheese. Each man had had the choice of one and a quarter pounds of salted beef or three quarters of a pound of raw pork. Clark had taken beef, knowing it would not spoil as quickly. He had wrapped the meat in cloth, then leaves, in order not to stain the haversack. In addition, he still had a few sweet oranges, a rare treat for the men enterprising enough to have hustled them from a load brought into Fort Brooke from Cuba the day before they marched. He had seen a few men drop their prizes along the way as the days passed, more eager to lighten their burden than to enjoy the treat.

Behind his bayonet hung a round blue wooden canteen with a cork stopper and U.S. stenciled across its seven-inch face. It had a capacity of twenty-two ounces, could be dipped and filled in any pond or stream. The forage bag and canteen were supported by canvas straps across the shoulder and chest. He was armed with an 1816 model .69-caliber smooth-bore flintlock musket, five feet long, eight pounds of steel and walnut stock equipped with a leather carrying strap. His left hand gripped the strap just below his shoulder.

Captain Fraser rode close behind the advance, the black interpreter staying close. Luis spoke four languages, English, Spanish, French, and Seminole, and had been hired from his owner for twenty-five dollars a month. He had taken the surname of his master, Pacheco, who owned a fishery at the little village of Sarasota fifty miles south of Fort Brooke. He had told Clark that it had been his ill luck to have come up to the fort on an errand for his master a couple hours after the command had left. He’d been hired on the spot, sent to join them. Clark figured he wouldn’t be much help unless they came on Indians who wanted to talk instead of shoot. The slave, barefooted, wore a cast-off army jacket over worn shirt and trousers. He carried a musket.

Behind Clark tramped another ninety or so men. Word had come before they had ever left the fort that two hundred and fifty Seminoles were lying in wait at the Big Withlacoochee. A fellow couldn’t help but wonder what kind of fool would send one hundred men against two hundred and fifty, but nobody had asked his opinion. The command had reached the Withlacoochee the afternoon of the fourth day. It had been a tense time with more joking and swearing than usual, but they had made that crossing, like the others, without trouble. Officers and men alike were still watchful but now more at ease. Seminoles were out there all right, no doubt about that, but out of sight, out of range, watching, waiting. For what, Clark wondered?

Earlier, pulling out of last night’s camp, sky oozing rain, Major Dade had told them, “You can’t put your muskets on the supply wagon as it would be unmilitary, but you can carry them under your greatcoats to keep your powder dry.” Now, couple of miles from camp, the drizzle gone, a cool breeze, some men who still wore the heavy coats had pulled them open, taken their weapons out, turned them muzzle up, shrugging an arm back through the black leather sling, working the buttons back through the tight wet buttonholes one by one. The rest continued as they had started, muskets under their greatcoats, over their short jackets, barrels down to keep them dry, coats or jackets buttoned from neck to hem against the damp winter chill.

Clark watched Dade as he drifted up and down the column, advance guard to rear guard, sitting his horse like a king, left hand casually holding the reins, right hand on his hip, a man who rode as though the animal was an extension of himself; never glancing down, around, eyes forward as though expecting Fort King to appear any minute, though it was a good two days ahead. Dade’s big black horse was tossing his head, snorting and frisky, sensing the ease of his rider. Dade was confident, you could see that. Must have been to have volunteered to lead this detachment.

The men were in good spirits, stepping right out. Until this morning they had had flankers eighty yards out, pacing the column on each side, men whose job was to flush an enemy if he was there. There had been no path for the flankers; they had had to push their way through whatever underbrush they encountered. It was slow, exhausting, and dangerous work. Men had been rotated every hour but they, as much as the oxen at the rear, had been a drag on the column. With the last river crossed, the opening out of the country, visibility good, attack growing less likely with every hour, Dade had pulled them in today, counting on the watchfulness of the several officers on horseback, the front and rear guard, to warn of danger.

This was their sixth day on the road. The crossings had been their weakest moments. Little Hillsborough wasn’t much more than a creek and the bridge still stood but they’d had to ford the Big Hillsborough. Two days later they’d patched the half-burnt Big Withlacoochee bridge and crossed with dry feet and the next day most had crossed the Little Withlacoochee on a log while horses, oxen, gun, and wagon had forded. Clark wasted little time in worrying, pretty much took things as they came, but aware that if the Seminoles had had the sense to hit them at the rivers, some men on the north bank, some in the water, the rest bunched up like sheep on the south bank waiting to cross, they could have been destroyed, shot down where they stood. He raised his head, looked out across the palmetto, through the pines. It would take organization Indians didn’t have, he told himself, to pull enough warriors together at any one time to make an attack that could overwhelm a command like this, armed and ready. If training and experience could keep them safe, they had enough and more.

Captain Gardiner, Lieutenants Basinger, Mudge, Henderson, and Keais were West Point trained. Maybe Henderson and Keais were only six months out of the academy but Basinger had five years of service, Dade, Gardiner, and Fraser over twenty years each, starting with the War of 1812. Clark felt wrapped in armor with more than one hundred well-armed men and experienced officers. Every soldier knew that organization and discipline won battles. Seminoles could run around like evil children, half naked, screaming, shooting, but they had no organization, no real authority over one another. Each warrior was independent, could join a fight or go fishing. Against a cannon, against men who could give and take orders, fire on command, stand shoulder to shoulder, an Indian wouldn’t have a chance. No matter that they only had fifty rounds for the six-pounder, half of that solid shot, designed for use against structures, not men. The deafening crash of its firing would terrify an Indian; the iron balls could smash a tree and scatter limbs like clubs among them.

He looked around. The underbrush was thin. Instead of the dense growth of the river valleys that could screen any number of Seminoles, palmetto had taken over, choked out the bushes. Stunted trees of the lowland were giving way to tall, high-limbed pine. ’Course, enough Seminoles wouldn’t need much organization, but now they’d lost their chance to come in close, ambush the column.

He looked over at DeCourcy marching on his left, caught his eye. Edwin DeCourcy was English, from Maidstone, five years older than Clark, his hair blond, his eyes blue. His father was an officer in the English army stationed in Canada. “Things are lookin’ good, ’igh ground from ’ere on in,” he said. Clark smiled, nodded his head. He took a deep breath. A few more months, then back to Greigsville. And Lucy.

The men around him were trudging steadily, most staring at the heels of the man in front, bored, thinking of food, girls, rest. We must look like a giant blue caterpillar rippling along he thought, light glinting off a buckle, button, musket barrel. He was conscious of DeCourcy at his side, the long loping swing of his legs. Why is he here? Why are any of us here? A hundred men marching through a jungle, a thousand miles from home?

He looked up, ahead, caught glimpses of Fraser, Pacheco, Mudge, the advance guard. He turned, looked over the men following, black hats bobbing against the green. He shook his head, stared at the sand of the road past his boot tips swinging, left, right, left. Nothing to do but march and think.

The pay, sure, food, clothing, and shelter, but what was behind it all? Why did the president, Congress, send us here? Clark couldn’t remember a single man he’d run into that wanted to be here, who had thought of coming back after his service, settling. This was no land for farming, he knew that. The thin, sandy soil would never bring a crop. The water was brackish, often tainted with iron, stinking of sulfur. The few settlers around the fort had pigs and cattle, but they were poor stock, gaunt, underfed. Mosquitoes, ticks, fleas, cockroaches, scorpions, other insects that he had never known in the north made life miserable day and night while rattlesnakes on land and moccasins in the water made travel dangerous. And men who had served through the seasons said that only for a month or two in the winter was the weather bearable, the rest steaming hot. It was no place for white men, never would be.

“It’s slavery, Mr. Clark,” Lucy’s father, Judge French, had said. Clark had told him of a poster he had seen in Geneseo, a poster that said the army wanted volunteers to go to Florida, protect the settlers. “It’s not the settlers they want to protect, Mr. Clark, it’s slavery,” the judge had said. He and Clark had been brushing down one of the judge’s prize horses, sweeping opposite sides down and back with curry combs. He paused and straightened, laid both arms across the animal’s back. “That land has been home to Seminole Indians for a hundred years, Mr. Clark. All along slaves have been escaping into the territory, been welcomed by the Indians. There are a few of those in Congress—powerful men, decent men, ex-president Adams in the Senate for one, Giddings in the House—who despise the institution of slavery, want to abolish it. But the majority, also powerful, represent the South. Slave owners, most of them. Seminole Indians harbor the slaves. To get their slaves back they’ve got to get rid of the Seminoles.”

Captain Gardiner was moving stolidly alongside the column on his horse, seeming almost to be pacing the men. Clark watched as he frowned down heavily at the men off his stirrup, then up toward the advance, back toward the rear, the column rippling like a blue wave against the green. With no flankers out, he and the other mounted officers were the eyes and ears of the command, watching, listening for trouble. As he came up alongside, Clark thought he looked uneasy, his grim face turning left, right, cigar in one corner of his mouth, smoke coming from the other. He had heard more than one man compare the little captain to a pot-bellied stove, an impression made stronger by his perpetual cigar, smoke bursting forth as though from a stove-pipe. He stood barely five feet, was almost as wide as he was tall.

Of the older, experienced officers, Gardiner and Fraser had seen plenty of fighting but Dade was the only one who had actually fought Indians and he seemed optimistic, but it was hard to ignore the captain’s obvious concern. It was clear that he had not agreed with Dade’s decision on the flankers, but there was no man to doubt his courage or his strength. Story was that as a cadet at West Point he had had a serious disagreement with another cadet over a girl and had wrapped a poker around the fellow’s neck with his bare hands. He had come away with the nickname “God of War.” If he was worried, maybe Clark should be too.

He looked out across the dark green saw-tooth palmetto again, the tall grass that crowded up along the road on both sides. This was Seminole country all right, but the risk of attack should be about past. The road had been cut ten years ago by eighty stout axmen through scrub oaks, palmetto, and grapevines near the rivers, leaving a virtual wall of nearly impenetrable undergrowth on each side where Seminoles could crawl and wriggle through to rise and strike with total surprise. Compared to that, this pine barren of the higher ground was like a release from prison. Across the palmetto, through the pine trunks straight as flag poles, sky brighter by the minute, a man felt like he could see forever. Reassured, Clark shook his head. If the Seminoles hadn’t struck by now they weren’t likely to try it here.

Good thing, too. Judge French had taught him to use musket and rifle, how to load, aim, fire, and the care of a weapon, had given him time and ammunition for target practice. With the help of a Seneca Indian he had learned to handle a knife. But he knew from his own lack of military training in the use of arms, even the position or duties of a soldier, that little skill was taught or expected of enlisted men. To turn a civilian into a soldier the army counted on discipline. From reveille at dawn to retreat at sunset there were fatigue details, cleaning and putting in proper order clothing, equipment, bedding, and quarters, often interrupted by roll calls, but no marksmanship practice, no standardized training program at the recruiting depot. Only some time after reaching his regiment had Clark been issued a musket and begun to receive a few hours a day of drill instruction. If it came to a fight, some of these fellows would have to learn fast.

He looked around, back toward the wagon, gun, and rear guard. Most men had been at least five days without a shave, their faces dark, hair sticking out from under their hats like damp straw, their clothes dirty and damp with rainwater and sweat, their bodies unclean. In spite of that, and danger, Clark thought they looked cheerful, confident, even eager. They’d make Fort King in a couple of days, be safe, have a rest.

Brevet Second Lieutenants Keais and Henderson were on foot with the men, usually near the head of their companies, sometimes drifting up and down the lines, giving a rebuke or an encouraging word here and there. Henderson, tall, thin, was attached to Gardiner’s company, while his classmate, John Low Keais, was attached to Fraser’s. This was their first field service since graduation. Back at the fort, Clark had heard that Henderson had applied for discharge soon after graduation in July. Approval of his application had been received at Fort Brooke only days before they marched, yet he had volunteered to stay with his company. Maybe figured he’d have a story to tell the folks back home in Jackson, Tennessee.

Lieutenant Keais, only a year older than Clark, had come down to Tampa Bay from New York in November. Finding Clark was from New York, surprised to find a literate, moderately educated enlisted man, Keais sometimes passed a few words with him. He told Clark he was glad to be in motion again. He had smiled. “When I received orders to come to Florida I was convinced that to come here would be equivalent to interring myself alive. Indians for companions, alligators, deer, bear, and what-not for playthings.” He waved a hand, taking in the weed-covered road, the palmettos, the forest backdrop, indicating that it was just as he had imagined. An orphan, he was obviously proud of the advancement he had won through his own exertions. He trudged along with the men, fine new uniform a little rumpled and dirty, a sword at his side, a small pistol in his pocket.

Lieutenant Basinger, mounted, rode near the rear of the column, in charge of the cannon, crew, and rear guard. A three-horse team was harnessed to the limber, a two-wheeled, single-axle vehicle carrying the ammunition box stocked with fifty rounds, both canister and round shot. Two men rode the limber bench driving the team. Attached to the limber was the two-thousand-pound double trail carriage and cannon, called a six-pounder from the weight of the iron balls it fired. The carriage was built of white oak, equipped with portfire stock, rammer, and handspike. The black forty-two-inch-long, thousand-pound iron barrel rode snugly between the high wheels, both limber and carriage painted with a mixture of Prussian blue and white lead matching the pale blue trousers of the men. Behind the gun marched the nine-man crew: one non-commissioned officer, two gunners, and half a dozen mattresses or gunner’s assistants, assigned numbers one to six.

And following the crew came the canvas-covered wagon carrying ten days’ rations and more ammunition for the muskets. Each wooden box of ball and buckshot cartridges weighed seventy-one pounds, held a thousand rounds when full. In addition to supplies, the wagon carried Dr. Gatlins’ two double-barreled shotguns, other officers’ gear, a mail pouch. The front wheels were thirty-six inches in diameter, the rear forty-two, giving it the appearance of rolling downhill. The two-inch axles were made of white oak, the bed of ash. The driver rode on a single board seat, U.S. painted in large black letters on the white canopy top over his head, canvas and bows swaying from side to side. The wagon was drawn by three oxen whose top speed was one mile per hour at best, still an anchor on the tail of the column. Finally, some fifty yards back, the rear guard followed—half a dozen men, muskets at the ready, looking left, right, back.

Stray dogs that had joined at Fort Brooke trotted alongside the column, some staying close to the men who had thrown them an occasional scrap, most independent, pink tongues lolling from their mouths, noses to the ground, sorting through invisible spoors that covered the ground like a web. Clark hitched his pack a little higher. We’re all right, he thought. We’re all right.

A dog bayed off to the right, others rushing toward the sound. Men jerked out of their thoughts, stared. Captain Fraser, with Pacheco still beside him, left the advance to investigate, moved back past Clark, then pushed out through the heavy palmetto.

Fraser’s face was narrow, nose long and sharp, his lips thin. His forehead was high, thick black hair brushed back from a widow’s peak, his eyes as large and dark as black olives. Fellow officers described him as “gay and gallant.” Clark could understand the slave sticking to him like a sandbur. He had overheard Fraser earlier remonstrating with Dade over the risk to the black man in being used as scout, protesting that if he were found by Seminoles he would likely be killed. “Major,” Fraser had said, “it’s dangerous to send this man on. You don’t know what the Indians will do.” Dade had dismissed his concern with a wave of his hand. Fraser had turned to Pacheco. “What do you think about it, Luis?” Pacheco had replied, “If the Indians catch me, Massa, they’ll kill me sure.”

Word came back up the column minutes later; only an ancient gray horse gumming the stiff winter grass. Fraser and Pacheco returned, passing the long column of men to follow again in the wake of the advance.

Clark glanced back at the sound of the major’s voice, saw him riding up from the rear, turning in his saddle, one white gloved hand in the air, calling out to the men, “Have a good heart. Our difficulties and dangers are over now. As soon as we arrive at Fort King you shall have three days rest and keep Christmas gaily.” The promise of reward brought smiles, shouts, hurrahs. Dade paused near Clark, turned off, sat watching the column pass in review.

The road was bearing a little to the left, the glitter of sunlight on water beginning to wink between the pines ahead and to the right. It was like walking on a brown carpet through a cathedral of pines. Clark, staring through the trees, frowned. In a moment something had changed. He looked around, left, right, up in the tall pines, across the sawgrass around a pond, then down, along the column, front, back.

The pond, maybe three, four hundred feet across, bordered with green reeds, was in clear view now on his right, maybe sixty yards away. He looked, then stared, suddenly frowned. No waterbirds, no sound. None. Only the soft brush of men’s boots against the pine straw, the rustle of palmetto. The trees were silent, no quarreling of jays, no scolding of gray squirrels. The world was holding its breath. He wondered if the major, if anyone else, had noticed the silence. His scalp tightened, he felt an instant chill. He clamped his teeth, gripped his slung musket with his left hand, swallowed hard, jerked his head from right to left, pond to forest. Something was terribly wrong.