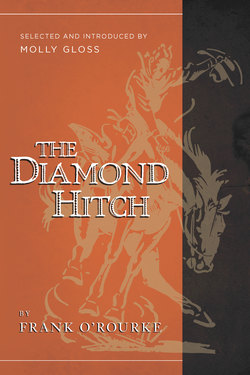

Читать книгу The Diamond Hitch - Frank O'Rourke - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

HE WAS NOT an old man but he had lived a good many hard years in his time. He got down from the morning passenger in the clear, sweet air speckled with engine soot and carried his gear through the depot waiting room into the street. He had sat up overnight on the smoking car, rolling Bull Durham, wondering if the job was still open.

He was thin and gaunted out, his face was deeply wrinkled and those lines crossed his sharp jawbone corners into the corded muscles of his neck. Weather had burned itself into the saddle-brownness of his cheeks and down the reddened, open V of his pull-over wool shirt. His hands showed the callused, thick-healed burn scars that came from the rope and the reins, his fingers were bent and three, once broken, had set crookedly. He walked deliberately on worn boot heels and, from behind, he had the stoop of an old man; but his eyes were a happy gray flecked with hazel and had not yet turned as old as an old man’s treasured memories.

He crossed the street to the Chink restaurant and dropped his gear beside the first stool. When a man was broke he was always hungry, even if he was sick he was still hungry. Dewey Jones ordered ham and eggs and ate slowly, thinking back over the reasons that brought him here.

At the start of the Fort Worth Fat Stock Show he had gotten in a fight with a big army sergeant. After that, old John Henry led him around two days with his eyes full of hamburger meat. That ruined his chances for the money until the final night when he picked up twenty-five dollars riding Ross Jackson’s Seven G horse in the exhibition show, and grabbed another twenty-five bulldogging a steer. He bought a ticket to Trinidad, rode over the pass to Raton, and ran into Mike Cunico. Mike showed him a letter from the Flying A outfit in Arizona, wanting a cook and horse breaker right away. Dewey Jones bought his ticket to Holbrook and now, eating breakfast, owned a dollar and eighty cents to his name. Breakfast was taking a seventy-cent bite from that thin roll, and he wasn’t even certain of the job.

He looked down on his gear, saddle and chaps and spurs, bedroll holding his quilt and two blankets wrapped in the paraffin-treated tarpaulin. He scratched a match on his worn Levis that betrayed the threadbareness of the young-old man who had sat too many broncs and had flown off before the final whistle.

He smoked over black coffee, the man who had known too many jobs, ridden too many miles, and owned to his name the gear beside the counter stool and the clothes on his back. Dewey Jones paid the check and carried his gear back around the depot where he heard cattle bawling in the stock-pens. He walked on down toward the first chute and watched a crew loading on steers in the choky brown dust and rising day heat.

Dewey Jones counted thirty-some pens facing the alleys, with gates spaced regular so a crew could cut out small bunches and fill up a car. He admired the way the crew worked their job on horseback, driving the cattle up the alley. He saw one man outside the alley fence, prodding stubborn cows with a stick, and awhile later that tall, gangling man peered at him through the dust and yelled a surprised greeting.

“Dewey Jones—what you doin’ way out here?”

Dewey Jones said, “Howdy, Raymond,” and watched the tall man prod a last cow and then come around from the alley fence.

Raymond Holly was a comical cuss who was once kicked in the jaw by a horse. The jaw healed crooked and the teeth laid down so Raymond chewed on their sides. When Raymond talked he jabbed a finger into a man’s chest and slobbered all over him, talking through those flat teeth. Raymond shook hands and started jabbing and talking as if they had parted only yesterday. It was all of four years, Dewey Jones recalled, since he last saw Raymond at the Las Vegas show.

“How far to Flying A headquarters?” Dewey Jones finally asked.

“Twelve miles,” Raymond said. “These here are Flying A cattle, Dewey. That’s the general manager right over there.”

Dewey Jones turned and saw a wiry man of about fifty coming down the chute platform from the last car. He said, “Reckon he still needs that cook and horse breaker?”

“He sure does,” Raymond said. “His name’s Hank Cochrane. Go over and jump him.”

Dewey Jones said, “Thanks, Raymond,” and went over to the chute and introduced himself, showed the letter Mike Cunico had received in Raton, and popped the big question; and right off, studying Cochrane, did not find any particular admiration for the man. Cochrane rubbed the letter between his thumb and forefinger before he said cautiously, “I need both. Can you handle it?”

“I don’t know how different it is here,” Dewey Jones said honestly.

“You savvy a pack outfit,” Cochrane said. “You know a diamond hitch?”

“Yes,” Dewey Jones said.

“The ranch is all pack,” Cochrane said. “Ain’t been a wagon on it in fifteen years. Pay is eighty-five.”

“That’s okay,” Dewey Jones said quickly.

He decided that Cochrane was more man than he’d figured on first size-up. Cochrane had judged him and figured he’d do, at least on the surface, and besides Cochrane was in a tearing hurry to ship his cattle out. Cochrane said, “We got a horse you can ride back. Tomorrow morning you pick up the chuck-wagon teams and come back to town and get your bill of groceries for ninety days.” Then Cochrane gave him another, sharper stare and added, “You want anything else, smoking tobacco, clothes, you get it with the groceries and charge it to the ranch.”

“Thanks,” Dewey Jones said.

“All right, go meet the boys.”

Raymond Holly was waiting down the fence. Dewey Jones followed him to the back pen and shook out his hair blanket while Raymond brought up the extra horse, an old cutting sorrel about fifteen years old who grazed along with the herd coming in. Dewey Jones slapped the old sorrel and spoke a few words, saddled up, and rode out with Raymond to join the crew.

He met Jim Thornhill and Driver Gobet and George Spradley. They didn’t say much, just smoked and sized Dewey Jones up and reserved judgment. They stood in the depot shade while Cochrane made out the papers for shipping the thirty-one cars of cattle to the Flying A grazing land in California. Then Cochrane came around the depot and said, “Let’s pull stakes,” and led them out of Holbrook on a dirt road that ran south across the level plateau country.

The road wound through arroyos and over level flats toward Snowflake and Show Low. They rode a bare land sprinkled with sage and chamiso, with a few stunted cedars growing in the shade of arroyo banks and along the slopes where topsoil was thicker. Cochrane took the lead, the others strung out, and Raymond Holly brought up the rear with Dewey Jones.

Raymond hadn’t changed a bit. He was always eager for talk, he fairly begged Dewey Jones to start asking questions like any new hand was bound to. Dewey Jones let him slobber a reasonable time before he said, “Raymond, what kind of an outfit is this?”

Raymond sighed with relief, coming unstoppered like a bottle of home brew. “Greasy sack, Dewey.”

“They got a pretty good string of horses?”

“Fair,” Raymond said. “But they ain’t broke out no young stuff the last two years. The horses is gettin’ run down. Boss bought thirty head from the Bar R, that’s what you’ll be aworkin’ when you get time off from cookin’.”

Dewey Jones wondered how much time he’d have off from cooking on a pack outfit. He said, “How’s the watering places on the ranch, Raymond?”

“Pretty good in some spots, not so good in others.”

“They got decent corrals?” Dewey asked. “Good bronc pen?”

“Yup.”

“These bronc pens,” Dewey said. “They round corrals with a snubbin’ post in the middle?”

Raymond squinted a moment in thought. “Well, they’s a good one at Cherry Creek made outa aspen poles with wire wove in between. That’s our headquarters for the long stay, and our first move.”

“Where’s the next move?” Dewey asked.

“Hole-In-The-Ground.”

“Where’s that?”

“Way to hell and gone from headquarters,” Raymond said. “We go to workin’ from there on back.”

Dewey Jones frowned. He had to build camp on water and when he had to shoe a bronc or work around, away from the cooking, he’d have little time to haul water up from any far place. He said, “How far these corrals from water?”

“On Cherry Creek,” Raymond said, “you’re right on water, just out of dust range. But that Hole-In-The-Ground country, well, you got to pack it about a hundred yards up the hill. Use the burros, put a ten-gallon keg on one burro, two keg’ll last the day. The wrangler’ll handle that and the wood.”

“I know,” Dewey Jones said shortly. “What about this string of broncs. They pretty big stuff, any well-bred, or just common mountain ponies?”

“Just common,” Raymond said. “They won’t give you much trouble, Dewey, not the way you can ride.”

Dewey Jones accepted Raymond’s compliment and rode in silence, thinking he wasn’t much shucks as a bronc rider considering his present condition. A dollar-ten in his pockets and the clothes on his back. Then he straightened and glanced at the country and drummed up a dust-caked grin for Raymond.

If he could stick for three months, he’d come back to town with a decent grubstake and, this time, he’d get on the train and head for Las Vegas and the big Fourth of July show. No drunk this time, he promised himself, no throwing it away. Then he remembered all the times in the past, all the drunks and the bad mornings and the washed-out feeling, and hunched over in his saddle and rode in silence through the rising dust.

A man made himself big promises and, like the wind, they kept on blowing ever hopeful until life was gone. But there had to come a time; there must be a time in every man’s life when he corked the last bottle and took the train.

Cochrane led them down a long grassy slope into ranch headquarters at suppertime. Dewey Jones unsaddled and turned the old cutting sorrel into the big corral and followed Raymond around the blacksmith shop to the ranch house. They washed at the wooden stand outside the kitchen door and faced the soft night wind, rolling a smoke, waiting for supper. Dewey Jones looked the home ranch over critically and liked what he saw; and just then the cowboss rode in from the south and shook hands and Dewey Jones knew that here was the real boss of the Flying A.

Hank Marlowe was a little bitty dried up fellow with a thin leathery face, the kind of man who didn’t know buying or selling cattle, but sure knew them on the range, where to catch, how to handle, where to run. Cochrane was the storekeeper who ran up the figure columns, but Dewey Jones had more respect for the Hank Marlowes. He knew what they could do. Hank gave him an easy first look and headed inside, the cook yelled, “Come get it before I throw it away,” and Dewey Jones followed the crew into the kitchen for supper.

He kept his mouth shut and listened, and thought over everything he’d noticed about the home ranch. The ranch house was L-shaped, built of reddish-brown sandstone mortared with adobe mud and flat-roofed with big viga pines that came, Raymond told him, from near the ranger station at the foot of the Mogollons up Hebron way. The west end was private quarters for Cochrane’s family, the kitchen occupied the middle, and the lower leg of the L facing south was the big bunk room.

Down by the corrals Dewey had noticed the old up-and-down bellows in the blacksmith shop, with plenty of ought and double-ought shoes for the small mountain horses. The big corral had long feed troughs for cotton-seed cake. The crew brought cattle down from the hills, fed cake and gentled them to the sight of humans before making the final drive to the train. The home ranch was about two thousand acres fenced into two big pastures with fine grass, and everything was in first-class condition.

“Comin’?” Raymond said.

“I’ll hang around,” Dewey Jones said.

The crew went into the bunk room and Dewey grabbed a dish towel and began helping the cook clean up. Bob Buford was about sixty-five, bald-headed and stumpy, a typical Irishman who threw his brogue around reckless and, like most cooks, started right in giving Dewey the low-down on the ranch. Buford was an old railroader who’d lost one hand on the Denver & Rio Grande long ago at Durango, and what with telling Dewey all that personal history, old Buford filled him in on the crew. It was funny how those men, ridden with and seen less than a day, had already taken certain shape in Dewey’s mind. Old Buford elaborated on each one, and Dewey Jones felt pretty good inside because his own first judgments were borne out.

George Spradley was forty, one of those real quiet, good cowboys who came from Young, Arizona, and had a wife and two kids. He was five-eight and weighed around one-fifty and sported a big handle-bar moustache. His riding partner was Driver Gobet, old Buford explained, and Driver was a good man, taller than Spradley, slender and well built, with a hatchet face spilling down sharply behind a long nose. There was Jim Thornhill, called Thistlepatch, who was an easy six-two and weighed over two hundred pounds. He had sandy hair and red whiskers, he talked in a slow drawl and didn’t say too much. Old Buford explained that Thistlepatch was now twenty-five, a Montana boy who’d left home at thirteen and worked down into Arizona and been riding ever since on different cow outfits, the Cherrycows, the R4, at times for the government on the reservation keeping outfits off the Indian grass, and finally for the Flying A.

Buford began talking about Raymond Holly, but Dewey cut him off because he knew Raymond from way back. That brought them to Hank Marlowe and old Buford spared no praise regarding the cowboss. Buford maintained that Hank was the best roper Buford knew, one of those men who could walk out in the morning and say, “What do you want?” and take another man’s rope and ketch, either hand, in nothing flat. Hank had grown up around Winslow and spent his childhood roping wild burros, and now he was rated the best cowboss in the country.

“Bob,” Dewey Jones finally said. “What kind of a bird is this Cochrane? How is he on feeding the boys?”

“Damned penny pincher,” Buford said. “Saves pennies on the groceries.”

“How long you been here?” Dewey asked.

“About eighteen years,” Buford said. “Cochrane’s the first bastard I’ve worked for, but his wife’s a fine woman and they got a good kid.”

Dewey Jones said meaningly, “I’m getting groceries tomorrow—”

“Buy what you want,” Buford said flatly. “Hank’s the cowboss, he feeds his men. Cochrane won’t know what you buy because the bill goes to the Los Angeles office.”

Old Buford didn’t tell Dewey Jones what to buy, but he did guess that Dewey might be a greenhorn on pack outfits, and so began giving the low-down on that subject. “Pard,” old Buford said passionately, “you sure got to watch them goddamned ornery burros. Them sonsabitches’ll rifle camp every time you get ten feet away from ’em.”

Dewey said, “Which ones are bad?”

“Them kitchen burros,” old Buford said. “Tom, Jerry, Jim Toddy, and Benstega. Them four with their black hearts!”

“You must know ’em,” Dewey Jones said.

“Know ’em! Lemme tell you!”

Old Buford began working up a big head of steam, but Dewey Jones waved and escaped into the bunk room, found an empty bunk and unrolled his bed. He lay back and smoked and listened to the boys talk, because you could learn more just listening, getting the real feel of an outfit. He felt their respect for the cowboss, but any time Cochrane’s name was mentioned it came offhand and gave him the feeling none of the boys thought too much of the G.M.

He smoked a final cigaret and closed his eyes when Thornhill snuffed out the lamp. Nobody had asked him any questions. They were all reserving judgment until he proved up. Raymond turned in the next bunk and said, “‘Night, Dewey,” and Dewey Jones mumbled, “‘Night, Raymond,” and let sleep take him down the long, soft trail with the sore-muscled dreams of gone shows and bad rides and carnivals, of women he’d known and drunks he’d been on, of twenty-eight years spent and gone. He didn’t move until five o’clock when Raymond shook him awake and old Buford yelled stridently.

“Come and get it!”

Cochrane showed up to give the day’s order at breakfast. Cochrane told Dewey Jones to get the chuck-wagon team, drive to town, and get a bill of groceries to last ninety days. Raymond went out and had the four chuck-wagon mules ready when Dewey came down from the house. Raymond showed him the harness in the tackroom, wished him luck, and hurried off to saddle up and join the crew. Hank Marlowe said, “See you tonight, Dewey,” and led them off about the day’s business. Dewey Jones harnessed the mules and headed for town, making notes all the way, studying out his order for Babbitt Brothers Mercantile Company in Holbrook, letting the mules follow the road, paying no attention to the country as he licked his pencil stub and made out his order. When he hit town and entered the store, he had the bill nearly ready for the clerk.

And right off the bat his first item made the clerk laugh. The clerk said, “What in hell are you doing with fifty pounds of corn meal on a cow outfit?”

“Listen,” Dewey Jones said stiffly. “Onions and corn meal and sage make a good dressing for roast beef where I come from. You got any objections?”

“No,” the clerk said.

“All right,” Dewey Jones said. “Let’s get to popping.”

The clerk grinned and began filling the boxes. Twenty-five pounds each of onions and pinto beans, hundred and fifty pounds of Hill Brothers Blue Box Coffee, the one-pound square boxes only because Dewey Jones used a pound and a half for breakfast, and the other pound and a half for supper; then twenty-five pound boxes of dried apricots, prunes, and peaches; four hundred pounds of flour, ten pounds of Arm & Hammer soda, ten pounds of salt, four pounds of pepper, sage for the dressing, two hundred pounds of sugar. With these staples, Dewey Jones ordered five dozen eggs and forty pounds of bacon and fifty pounds of potatoes. He pulled down fifteen pounds of P&G yellow soap for the hard water country they were going into; twenty-five pounds of lard in a big pail, and six cases of Pet milk in twenty-four can boxes.

He grinned a little then, thinking how he had a dollar-ten in his pocket and yesterday he was just hoping for luck; and here he stood buying groceries and spending money like a drunk Swede in a parlor house. He added three cases each of tomatoes and corn, six gallons of molasses, and baking powder. Then he gave the clerk his own personal order and asked for a separate bill. The clerk got him two pairs of Levis, two shirts, one Levi jumper, half a dozen pairs of socks, two suits of light underwear, three cartons of Bull Durham, and an extra carton of papers.

“That does it in here,” Dewey Jones said. “I’ll swing around back.”

He drove the chuck wagon behind to the loading dock and helped the clerk carry out the order. They topped off the load with sacks of clean oats and cotton-seed cake, Dewey signed the bills, and crossed over to the Chink’s for his meal. He ate with a fine appetite and rolled a cigaret on the sidewalk, staring sideways at the saloon doors ten steps on his right. He was heading out for three months, a long, rocky road before he’d get another drink. He ought to have a couple just for the road and then head for the ranch.

Dewey Jones started toward the saloon, sniffing the malt odor that drifted through the swinging doors; and then he stopped and walked across the street and down the alley toward the loading dock. If he couldn’t trust himself yet, he had no business trying two drinks and maybe signing away his unearned pay and ending with twenty. He climbed aboard, shook out the lines, and spoke gently to the mules.

“Good luck,” the clerk called.

“Thanks,” Dewey Jones said. “See you in July.