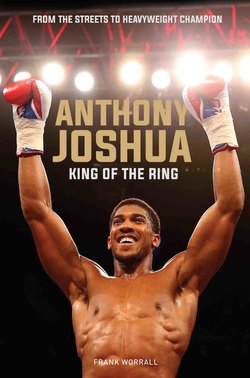

Читать книгу Anthony Joshua - King of the Ring - Frank Worrall - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

LONDON CALLING

ОглавлениеAs the days counted down towards the London Olympics Anthony felt a knot of excitement and anticipation in his stomach. He had certainly come a long way in those four years since putting on the gloves for the first time, and now he could see a truly tangible reward looming if all went to plan. He remained confident that he would end up among the medals but, being AJ, that was only the long-range aim: he wanted, and was working towards, the gold. Never a boy to settle for second best when he set his mind to something, he trained like a demon and maintained the belief that he would emerge triumphant in the battle to become super-heavyweight champion. It was not an ego trip as he saw it, more a rightful end product after all the work he had put into it. All the early-morning runs, the pain in the gym, the hours and hours of sparring – why would he have gone through all of that just to be happy to have participated? No, as always, Anthony was only interested in the top prize. That was his mindset as London 2012 loomed; super-confident, but not arrogant, determined, but not obsessed, and giving 100 per cent in training, but not to the extent that he would have nothing left in the tank when the competition finally began.

Anthony Joshua was a winner, pure and simple. He went into every bout expecting to win, knowing he had done everything in his power to achieve that ambition, and his optimistic outlook meant that he had the mental strength to back up his ever more powerful physique. Those long hours with the GB boxing team trainers at the Sheffield Institute of Sport had paid off. Anthony was a different man from the one who had tentatively sparred for the first time back in 2008. Gone was the callow youth; in his place was a formidable, super-fit athlete, who would become even more powerful as the years rolled on. The evolution of Anthony Joshua, boxing golden boy, was well under way by the time of the Olympics that glorious summer of 2012.

Anthony would be the first to doff his cap and admit that he owed a hell of a lot to one man, in particular, as he went for gold: Rob McCracken, the supremo of GB Boxing and, ultimately, the man who would work for him, training him and encouraging him in his corner as his full-time coach during that super-fight with Wladimir Klitschko almost five years later. As GB Boxing’s Performance Director Rob had worked miracles even prior to the Olympics. It was down to his efforts, his vision and his belief that Great Britain could reign supreme once again in the annals of amateur boxing, that the country would end up with three champions during the event. And that was a considerable achievement, given that three years previously he had taken over a squad that was in disarray and with extremely low morale, having left the World Championships in Milan with zero success. No medals and no hope.

That was all about to change under McCracken’s brilliant, sometimes belligerent guidance. The has-beens would be shaken up and knocked into shape, the end result being the golds that Anthony, Nicola Adams and Luke Campbell would win in London. It helped, of course, that Rob knew about the art of boxing from his own experiences at the coalface – he himself had turned pro in 1991 in the Light-Middleweight division and, three years later, won the British title by outpointing Andy Till. In November 1995, he moved up to Middleweight and won the Commonwealth title by outpointing Canadian southpaw Fitzgerald Bruney. Eventually, he had so much success that he was considered the Number One challenger in the WBC rankings. Rob retired from the ring with a record of 33 wins and 2 losses, including 19 knockouts.

All this meant that he knew what he was talking about as head coach of the Olympics team and, just as importantly, the boxers under his command knew what he was talking about given his background, experience and record as a boxer. He had been there and done it, and had the T-shirt to prove it after fighting his way through so many bouts himself over an educational decade. As he would tell BBC Sport, ‘Dedication and discipline are keys to producing a tremendous boxer, regardless of what talent he or she has got. But you learn from your mistakes and every mistake I made I pass on to the boxers and make sure they don’t do it.’

It wasn’t just the training and sparring, though. McCracken revolutionised GB Boxing with many other innovations, including concentrating on nutritional and medical well-being, as he explained: ‘My job was to get the right team in place, bring more coaches in, more support staff, which means we can have more boxers training with us. We’ve embraced sports science. The first thing I did when I came in was let these people practise their techniques, crack on with what they’re trained in. If a fighter doesn’t make it, they’ve only got themselves to blame. They’re full-time athletes, everything is catered for on the medical and nutritional side, they’re told what to do when they go home. They get every chance to succeed.’

This advanced approach was music to Anthony’s ears. He loved innovation and anything ‘hi-tech’ that could help raise his own game – as we will note in a later chapter about how he set up his own specialist team when he turned professional. Anthony knew at once that McCracken could bring that extra edge to his boxing; that this was a man who could indeed take him to the next level, with his team of strength coaches, nutritionists, physios and performance analysts, and he was delighted that Rob was to be his Olympics supremo.

In 2011, Rob told the press how the build-up to the Olympics was panning out. He admitted he was pleased with the way Anthony and the others were working towards their goal and how they were coping with changes in the rules and his innovations at the Sheffield centre of excellence. He said, ‘In terms of preparation, the big improvements I’ve seen are in the way the squads have adapted to international boxing: to the new scoring system and the change to 3x3 rounds. They are very professional for youngsters. They have travelled the world and are not fazed by anything. I’m very pleased with the way the boxers are developing.’

Anthony received an early Christmas present at the start of December 2011, when it was announced he had made the cut for London 2012 and would be part of the Olympics squad. It was a massive achievement, and he had celebrated by first telling his beloved mum, Yeta, and enjoying a cup of tea with her. Then it was down to London and the Olympic Stadium to pose for pictures for the next morning’s sport back pages of the national papers, and to give his views on how he saw the bouts panning out for the GB hopefuls. Anthony was one of five boxers who had been officially selected for the London Games after sealing their qualification at the World Championships in Baku, Azerbaijan, in October. The others were flyweight Andrew Selby, bantamweight Luke Campbell, light welterweight Tom Stalker and welterweight Fred Evans. Anthony told reporters how effective the Sheffield centre had been in helping him make the Olympics cut. He said: ‘GB Boxing have got a lot of Lottery funding now. They’ve got coaches there, they’ve also got a nutritionist, a psychologist, a physiotherapist and I think we’re being very well prepared. Behind the fists, there is a lot of science. It’s about leaving no strand unturned and going in there with every advantage. It just makes you so much more difficult to beat if you can do that.’

Rob McCracken congratulated the famous five, saying, ‘Since I took over as Performance Director in November 2009, the GB Boxing squad has performed consistently well at major championships. To secure five Olympic qualifiers at our first opportunity was very satisfying and a great achievement by the boxers who have all worked hard to secure this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to compete at a home Olympics. The five boxers are all a credit to the squad and if they box to their full potential then every one of them has the talent and ability to do well and secure a medal.’

Matt Holt, the Programme Director for GB Boxing, was also confident of success, saying, ‘We’re in a great place. The successes that we’ve had across the three major championships this year have been absolutely fantastic. At the men’s Europeans we put two of our boxers on the gold medal podium and they both qualified for the Olympic Games. In Baku, we had three boxers get to the final, which has never been done collectively by GB boxers before, so that was fantastic, too. We were a little bit disappointed that one of those silvers wasn’t converted into gold, but that’s what we’ll be hoping to do in London.’

The Sheffield centre had been a definite plus point as Anthony now fine-tuned his work there. It was plush and modern; a dream for kids like AJ who had been used to rough-and-ready boxing gyms and slumming it in B&B accommodation when training. Now they could train and develop in world-class surroundings with world-class facilities. Rob McCracken would later say it ‘covers everything including medical issues and physio, strength and conditioning, nutrition, psychology, lifestyle and performance analysis and has been a massive factor in our success, giving our boxers a performance edge over their opponents.’

The £1million state-of-the-art, purpose-built boxing gym opened in 2009 and would prove so positive for Anthony as an ideal working environment that he would use it even when he turned pro and won his world heavyweight titles, returning ‘home’ to enjoy the facilities that had helped him win gold in 2012.

An indication of its quality came a year after its official opening when the USA Boxing squad paid a visit. They had heard all about what was on offer but wanted to see for themselves if the hype was truly justified. They soon found that it not only was, but that it exceeded expectations and was, as the press would have it, ‘a knockout’. Ed Weichers, Head Coach for the USA’s boxing association, told reporters, ‘We have been training for the Atlantic Cup in London but really we were interested in the English Institute of Sport in Sheffield. We know that if we’re going to have competitions in the UK we will be welcome to use this facility.

‘The venue is very impressive, they have everything we have. I love the utilisation of space with the number of bags and rings. They have some highly technological advances in terms of video review and they’ve got a newly appointed Performance Director in Rob McCracken who comes highly recommended. I think BABA is really on the right track and we’re trying to do the same over in the US.

‘When the England team came over they were very focused, very disciplined, and competed tenaciously and they did very well. They won many more than they lost which speaks very highly of their programme. Sharing information and sharing ideas, concepts and dreams are just going to make all the athletes better. I’ve learnt a lot since I’ve been here and I’m going to learn a lot more during the rest of my stay. I think there’s a lot of respect and admiration for one another and just good healthy competition which is what it’s all about right now.’

Rob McCracken did indeed come ‘highly recommended’ and would once again prove that he was not a man who simply rested on his laurels when he encouraged yet more innovation to help Anthony and his fellow boxers the year prior to the Olympics. In 2011, it was revealed that the Sheffield centre was using a hi-tech ‘video capture’ system, the iBoxer, to give the boxers an additional insight into how they could improve performance. The system used a series of cameras to monitor boxers’ movements in the ring, which were fed directly to a series of touchscreen monitors in the gym. The athletes could then go over the footage between bouts in order to analyse and improve performance, define fight strategy and gain a better understanding of their opponents’ tactics.

Professor Steve Haake, director of Sheffield Hallam University’s Centre for Sports Engineering Research (CSER), a UK Sport innovation partner, explained just how it was working in training – and how it would, it was hoped, help the boxers at London 2012. He said, ‘Once the athlete has completed a three-minute sparring round or training session they can come out of the ring and get immediate video feedback on the aspects important to the session. The iBoxer system also stores the judges’ scores and videos for thousands of bouts, which can easily be searched using a laptop or touchscreen PC.’

GB Boxing’s full-time performance analyst, Robert Gibson, had trialled the system with the Olympic squad at Sheffield and could see benefits. He said, ‘Some of the things we’re looking at are to do with points-scoring dynamics. Where are points scored during a bout? What are the current gold medallists doing? What are we doing compared to them? Then we look at punch efficiency. How many punches were thrown per point? And if a point isn’t scored why not?’

And McCracken was similarly effusive, saying, ‘Performance analysis is an important part of our boxers’ preparations. It provides us with insight on their opponents’ strengths and weaknesses and, by providing them with this knowledge, builds confidence. The iBoxer system has supplemented our work in this area and enhanced the quality of our performance analysis.’

So it was little surprise that the system, developed by researchers at CSER in conjunction with the English Institute of Sport (EIS), won the Best New Sports Technology category in the MBNA Northern Sports Awards that year. It was certainly making an impression upon the boxers and trainers as they prepared for the Games. Another example of how McCracken was using technology to get the best out of Anthony and his team-mates – it was a hell of a long way on from the archetypal image of boxers working in rundown spit-’n’-sawdust gyms, spitting blood in buckets and shivering in the cold, as exemplified by the Sylvester Stallone Rocky movies!

As Dr Scott Drawer, Head of Research and Innovation at UK Sport, summed up, ‘Our work sets out to help our athletes and their coaches learn faster than their international opposition, and this is a great example of where increasing knowledge and understanding of the sport can give our athletes a real performance edge.’

Everything was being done to boost performance and help Britain’s elite amateur boxers hit optimum form just when the Olympics came around. There could be no excuses for total failure; not when so much money, time and effort had been thrown at the cause. Optimum body conditioning was key for Anthony. He had never carried any extra pounds but now he would become even leaner and meaner under the auspices of the Sheffield nutritional team. Like the other boxers, his food for each day’s training was pre-prepared and left in the gym fridge in an individual food box. It was carefully planned to give him maximum strength but to keep his weight at the right level too, a balanced mix of carbohydrates and protein as; he told the Guardian in July 2012, ‘I’ve just got to take it home and eat it … I’ll get some fresh meat, fresh fish, fresh salmon, maybe some potatoes. It’s important to stay close to my best fighting weight, even at super-heavyweight. My best is around 106.5kg. At the minute, I’m at 107.1kg. I wouldn’t want to be, like, 109kg. After competition you lose a lot of weight, sweating and so forth. I could weigh in after a fight at 104kg. If I sat back, that’s losing energy. So I have a shake, something to eat, put the energy back in. It’s all about smaller portions, no carbs at night.’

He and the other boxers stayed in flats close to the centre from Monday to Thursday as they prepared for the Games. Anthony would even return to the same accommodation when he turned pro – he admitted it was what he needed to keep his mind on the job. Not spartan, but certainly not luxury, the accommodation was modest and humble – just as he liked it before a fight. Plus, of course, he was near the gym and the facilities of GB Boxing. Back in the build-up to 2012, he and the team would then train at home over the weekend, while ensuring they had regular, and much-needed, rest periods. Good sleep was especially important to Anthony. He admitted he loved taking naps to recharge his batteries and considered them an important part of his overall lifestyle and training structure. He also made sure he saw pals and family as the Games got ever closer; he loved taking time out to smile and laugh with those closest to him. Never one for seeing a glass half empty, Anthony liked to live life and to enjoy it. Sure, he knew he had to put in the long hours and hard work while training but time out was also vital – as the Sheffield centre’s physiologist Laura Needham would point out in 2016. She told the Daily Telegraph, ‘Sleep is so important for recovery. We spend a third of our lives doing it and yet we devote so little attention to it. Take napping during the day, for instance. We like our boxers to nap either for 30 or 90 minutes. If they wake up after an hour, they are likely to be in the deepest part of sleep.’

McCracken knew that the smallest improvement could prove key at the Olympics and so he was also open to the idea of pro boxers helping out. To that end he enlisted the aid of one of the very best, Nottingham’s IBF super-middleweight world champion Carl Froch. Rob was Froch’s trainer as well as being the Sheffield supremo and was delighted that Carl felt able to put the home nation’s ten boxing hopes through their paces. ‘He trains with the squad, he joins in some sessions and he spars with some of them,’ McCracken said. ‘It is great for his speed and tempo, and it is great for them to do three or four rounds with him, he gets them to where they need to get. He has rubbed off on them a lot and I think they have rubbed off on him in some ways as well. I know he is coming down to London and he is really keen to see them do well because a lot of them are his friends as well, and hopefully they can push on and get the medals they thoroughly deserve.’

In June, just a month before the opening ceremony, the final boxing squad for the Olympics was named and Anthony and the team posed for another photo opportunity and a further question-and-answer session with the press. He said he was very confident that the team would do well and that there was a strong possibility that they would make the nation proud. ‘I think we can all go to the Games and achieve something great and bring boxing back up to where it used to be,’ he said. ‘We’ve had enough of bad decisions and fights outside the ring and all that stuff. I’m glad to be in this position but at the same time I’m not trying to be flash or cocky. I’m just trying to help put boxing back in a good place, and I think I’m part of a team that can do it.’

Every member of the group was a Games debutant but Anthony insisted they could beat the three-medal haul from Beijing 2008 – one gold and two bronze – and even equal the five-gong haul from Melbourne in 1956, when Britain came second to only the Soviet Union with two golds, a silver and two bronzes. He added, ‘Five medals is a tough ask but I think we’ve got the talent in this team to match it or even beat it. I don’t think the records are going to stop there. This team can keep getting better and better.’

The final teams looked like this:

Men: Anthony Joshua (super-heavyweight), Anthony Ogogo (middleweight), Andrew Selby (flyweight), Luke Campbell (bantamweight), Josh Taylor (lightweight), Thomas Stalker (light welterweight), Fred Evans (welterweight).

Women: Nicola Adams (flyweight), Natasha Jonas (lightweight), Savannah Marshall (middleweight).

And boxing promoter Frank Warren was convinced that Anthony would win a medal and that doing so would open doors for him to become a wanted man in the pro world afterwards. He told the Sun, ‘If London super-heavyweight Joshua wins gold he will be the hottest property in world boxing. Four years ago he had not even laced on a pair of boxing gloves but now he is one of the favourites to capture the top prize. Joshua, 22, had a fantastic World Championships beating reigning Olympic and double world champion Roberto Cammarelle and just lost out in the final to the home boxer Magomedrasul Medhidov in Azerbaijan. Standing at 6 foot 6 inches, supremely athletic with fast hands and feet, a big punch and a million-dollar smile, he is one of the faces of London 2012. Joshua will get a medal and I expect him to be in the final.’

As an interesting tangent, it was claimed in Nigeria that Anthony had wanted to represent the African country in 2012, given his Nigerian family connections – but that he was refused a spot in the team! The claims surfaced in Nigeria and were given credence by former Nigerian national boxing coach Obisia Nwankpa. The story goes that Anthony contacted the Nigeria Boxing Board of Control ‘about flying the Green and White’ at London 2012 and was ‘duly communicated by the authorities to join a national trial camp…but then there was a glitch.’

‘This was in 2011. Nothing was heard from the boxer; who was relatively new on the scene at the time, until the end of the camp,’ Obisia told brila.net. ‘Eventually, when he resurfaced again, there was nothing anybody could do about it. We already shortlisted the boxers for the Games and could not drop anybody for him, he should have been at the trials. There was no way we could have put his name on the list without participating at the trial, because everybody we selected took part.’

And in 2017, just days before AJ’s battle against Klitschko Obisia remained unapologetic about rejecting the champion back in 2012. He said, ‘I would do it again because we must always do the things the right way.’ No one connected with the Joshua camp would confirm or deny the story, but I am tempted to believe that AJ wanted to represent GB in 2012. He had put all his time and efforts into his work at the Sheffield centre of excellence and had been trained by GB coaches, so it made little sense to suggest that he suddenly had decided to opt out to represent another country, however much Nigeria remained close to his heart.

And, as the Quartz Africa website, which also ran the story, pointed out, it would be an unusual move given the quality of training and facilities Anthony enjoyed in Sheffield, as opposed to those in Nigeria which, it claims, would not be as good, ‘With hindsight, it’s difficult to say if Joshua would have done as well if he’d been representing Nigeria but history suggests that would not be the case. Over the years, several home-grown athletes have switched allegiances citing poor management and sub-par training facilities. Francis Obikwelu, the current European 100 metres record-holder, switched allegiance to Portugal after Nigeria’s athletics federation neglected to cover medical bills for an injury sustained while representing Nigeria at the 2000 Olympics.

‘It’s not just a Nigerian thing either. At the 2016 Olympics in Rio, at least 30 Kenyan-born athletes represented other countries. Similarly, half of Bahrain’s Olympic track and field team was almost entirely made up of Africans.’

Still, it offered yet another talking point in the ever developing narrative of a boxer who would be on the brink of becoming a star if he could shine at London 2012.

In another encounter just before the Olympics, Anthony crossed paths for the first time with someone who would become a good friend. Little wonder, perhaps, given that Troy Deeney, Premier League goalscoring machine, was also from Watford, as well as playing for the town’s football club. Troy had popped into a barber’s shop in the town for a quick haircut and Anthony was already in the chair. The duo struck up an unlikely conversation after Troy noticed that Anthony was eating as he had his hair cut.

Troy told the Daily Mirror, ‘I first came across Josh before he was an Olympic champion. I walked into a barber’s in Market Street, in Watford town centre, and he was in the chair. I noticed he had his food with him, and I thought it was a bit unusual to be eating while he was getting his hair cut, so I asked him, “What’s for lunch?” He explained he was a boxer who was going to represent Britain at the Olympics, and was going to run the five miles home, so he was just putting some fuel in the tank. I thought, “Fair play to you.” We just got talking. It was never a case of, “Ooh, you’re a boxer! Can I be your mate?” None of that s***. I just respected he was working hard towards a goal, and every conversation we’ve had since then has been straight down the barrel, no grey areas, no bull.’

Their friendship would be put on hold when Troy was jailed for three months for affray, in the summer of 2012 – the very time when Anthony was going for gold in London. ‘I was locked up when he fought at the Olympics,’ Troy added. ‘But I was banging on my cell door when he won the gold medal.’ They have since revived their friendship and Troy admits he is ‘proud’ to know Anthony, whom he calls a ‘role model’. They have much in common, both growing up in a tough area and both taking some hard knocks and making some bad mistakes along the way. But, ultimately, both have worked hard to put the past behind them and make amends with the way they now live their lives and by offering their help freely for charities and worthy causes.

After his unexpected meeting with Troy Deeney, Anthony became one extremely busy young man. The Games were almost upon him and he and his team-mates set up camp at the Olympic Village in Stratford, East London, on 24 July. They were undoubtedly surprised, if nonetheless delighted, by the welcome they received. No one had anticipated that the London Olympics would be the massive morale booster for the nation that they would turn out to be – but the omens were good that Friday, as Anthony and the GB team attended a welcoming ceremony after ‘booking’ into their accommodation.

Anthony told friends he was happy with his quarters. He was rooming with fellow GB boxer and the team skipper, Tom Stalker, and they spent some time acquainting themselves with the set-up and amenities. The village’s 2,818 flats had been fitted out to cater for 16,000 athletes and officials from 200 countries; it was reported that, among much else, it had needed 11,000 sofas, 170,000 coat hangers and 5,000 toilet brushes. And, given just how large an area the village covered, it was hardly surprising that a few athletes struggled to find their way back to their accommodation that first night!

Earlier, they had been greeted by a troupe of jesters and the Deputy Prime Minister, Nick Clegg, although he denied he was part of the troupe. Joshua’s team-mate, Anthony Ogogo, spoke for the group when he said that he had enjoyed the welcome ceremony, which also included performers on stilts and cycles singing to Queen’s ‘I Want To Ride My Bicycle’. Ogogo said. ‘It was amazing. It’s hard to explain quite what this feels like, but it’s exactly as I expected it would be as a kid. It’s weird walking around here with so many strangers seeing you in the tracksuit and just saying “Well done”. I can’t wait until my first fight on Saturday to do my thing.’

Mr Clegg believed it was the prelude to a successful Games, telling BBC News: ‘This Olympic Village is a triumph and I’ve already spoken to some of the athletes, who’ve said the facilities are the best they’ve ever seen. No doubt there will be a few ups and downs along the way but I think people are going to be so proud that Britain has been able to put on such a successful Olympics. This isn’t just about the athletes, it’s about the nation really coming together to support Team GB. This is the greatest show on the planet and I’m clear that the nation is going to love every minute.’

He would be proved emphatically correct in that assumption as the nation got behind the Games. They would prove to be something of a rallying call; harking back to a time when Britain had been truly great, after four tough years for the many in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008. Back in Fleet Street, we who had followed Anthony’s progress intently, and sensed he was something special, were now about to find out just how good he actually was – and whether he could justify the hype and the growing belief that he was a boxing great in the making. Could he follow in the footsteps of Audley Harrison and Lennox Lewis? Or would it all end in disappointment; a crushing anti-climax? The eyes of a nation fixed on the young man from Watford, whose destiny was undeniably – and literally – in his own hands.