Читать книгу Home Front to Battlefront - Frank Lavin - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

If I were giving a young man advice as to how he might succeed in life, I would say to him, pick out a good father and mother, and begin life in Ohio.

—Wilbur Wright, 19101

Growing up in the 1930s, Carl Lavin used to play tackle football in weekend pick-up games in his Canton, Ohio, neighborhood. Carl loved the feel of the football, the stiff-arm stops, the slip-throughs, and the straight-away runs.

Being tall for his age, Carl also didn’t mind the aggression of the game or the fact there were no pads or helmets. He enjoyed the rousing sport as well as the camaraderie and the playground heroics that came along with it.

But Carl’s love for the game was to remain on the field. His mother, Dorothy, was a serious pianist. She was an immigrant’s daughter who stood at average height, but wielded a big personality. She lived in a world of manners and modesty, not childish scrapes and stubborn grass stains. She was skeptical of the value of sport, and she was keen to make sure her boy did not injure his hands.

Dorothy had studied piano at a conservatory and played with local classical groups. It was no surprise that Carl was obligated to take piano lessons. Like any carefree boy, Carl never particularly enjoyed the lessons or felt he had any special aptitude for music, but such was his fate.

In 1938, as Carl was entering Lehman High, the school decided to upgrade its football team to compete as an official school sport—Canton was the birthplace of professional football, after all—and Carl asked his mother if he could go out for the team. His mother refused permission, pointing out that the school did not provide helmets or pads, so the game was not safe.

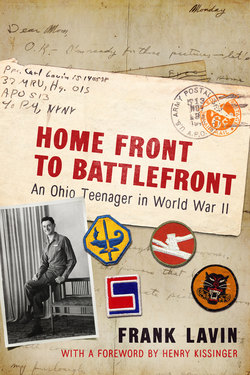

Figure I-1. Carl and Fred with Dorothy, c. 1930. Carl would be around six years old, Fred eight, and Dorothy thirty-five. Author collection.

Carl had a choice. He could tell his mother that he had been playing tackle football without protective gear for some time now, hoping the argument would win approval for school football. Or, if he confessed this activity, he might find that she would also prohibit him playing in the weekend pick-up games.

Carl decided to keep quiet, forgoing the chance to play at school but at least preserving his private freedom to play on weekends.

That was Carl as a teenage boy. He was smart and pragmatic. He was also very funny—and a bit mischievous, too. That tells you a lot about Dorothy as well. Always seeking the best for her boys, even if it did not seem so to them at the time.

Dorothy would practice the piano for hours a day, filling the small house with classical works. But she had smallish hands; her span was limited. There was one particular part of a Chopin étude that required a reach. She would frequently miss the note and stop her practice with a sigh, only to begin again.

Every time Dorothy came to the troublesome point in the étude, she held her breath. Carl would listen as that moment grew near and hold his breath as well. Dorothy tensed and Carl tensed. When she hit the note, they both relaxed. If she missed it, he joined her in a sigh.

Besides football and piano lessons, Carl was poetry editor of the school paper and a voracious reader. While Carl was often casual about schoolwork, he possessed curiosity and imagination.

On Carl’s bookshelves were the complete short stories of O. Henry and the works of L. Frank Baum. The former dealt with ironies and fatalism in the lives of everyday people, written by that well-known alumnus of the Ohio State Penitentiary. The latter dealt with the most amazing adventures possible. Get this—the hero was not a knight or a detective, but just a kid from the Midwest. This Dorothy appeared to be every bit as plucky as Carl’s mother, and from the same era as well. That kid from the Midwest faced a series of improbable dangers and it was not completely clear if she would ever make it back home.

Also on the shelf was his collection of postage stamps from around the world, a typical Depression-era hobby, allowing a boy to dream about far-off lands when he wasn’t able to go anywhere. Even at a young age, Carl started to develop a sense of the world just by looking at stamps from China, Argentina, Great Britain, and even that interesting stamp commemorating the 1936 Olympics, the one with the odd symbol on it; a swastika, they called it.

In December 1941, Carl Lavin was seventeen years old, standing six foot two and attending Lehman High School in Canton, a Midwest industrial town of about 110,000. Carl was a senior, and, even though it was the time of the Great Depression, he was fortunate to have a fairly worry-free life. He had a loving family, a dog named Spitzy, and the entire world in front of him.

Carl’s brother Fred was two years older and attending college at Miami of Ohio. Carl’s father, Leo, and Leo’s two brothers, Bill and Arthur, ran the Sugardale Provision Company, the family-owned business started by Carl’s grandfather, Harry.2 Sugardale processed and sold meat products and other foods, everything from ham and bacon to cheese and Birdseye Frozen Foods.

Harry had a fourth child, Elizabeth. She had married Lou Kaven and, while the couple was not involved in the family business, they lived in the same half-mile radius as the rest of the family. With Harry and his wife, Mary, their four children and their spouses, there were five households in a small area on the north side of Canton.3

Carl had it pretty good, considering. Lehman was a fine high school; Canton, a nice town. Life was pleasant. True, business was slow all around, and the Great Depression had gone on so long people began spelling it with capital letters, but the Lavins and the Canton community were persevering. The misery of the 1930s was receding, slowly.4

In fact, a few of the local family businesses had gone on to bigger things. The Diebolds’ safe company sold their products around the world. The Hoovers also built their cleaner company into a famous brand. The same with Mr. Timken and his ball bearings.

Sugardale wasn’t a national name, but it did its best to endure during those difficult days. The Lavins cut business hours and reduced expenses. By reducing the workweek from five days to three, Sugardale was able to survive without layoffs. Because the company endured, Carl’s family was in a better situation than most. Besides, Leo made good use of the days that were closed for business by taking the train to Cleveland to watch the Indians play.

Dorothy and Leo owned a house on 25th Street. It was small, but it was paid for. It had indoor plumbing and a telephone.5

The house was a little more than a mile away from the home at 7th and Market where Governor William McKinley had run his front-porch campaign for president, twenty-eight years before Carl’s birth. It was also about a mile away from the Hupmobile dealer at 2nd and Cleveland, where the National Football League had been established four years before Carl was born. And it was about two miles north of Nimisilla Park, where Socialist Party leader Eugene Debs gave the 1918 anti-war speech that got him arrested.6

The United States was a different world in 1940. Journalist Cabell Phillips offered an overview:

The population was 131.6 million in 1940, up a scant seven percent over 1930. . . . The GNP was 97.1 billion, with federal government expenses running at just under 10% of that amount at 9.1 billion. About 7.5 million people paid federal taxes, with the tax rate at 4.09%. Only 48,000 taxpayers were in the upper bracket of incomes between $25–$100,000. And there were 52 people who declared an income over $1 million. The average factory wage was 66 cents an hour and take home pay was 25.20 a week. Urban families had an annual income of $1,463 and only 2.3% of these families had an income over $5,000 a year.7

Along with a house, Leo also owned a LaSalle automobile, which he allowed Carl to drive—a pretty good deal for any seventeen-year-old boy.

One Sunday Carl took the LaSalle downtown. It was around 3 p.m., and he was headed home after having a bite at a lunch counter. As he braked for a traffic light, his uncle Bill happened to pull up alongside him, then started waving, trying to get his attention.

Uncle Bill rolled down his window, motioning for Carl to do the same.

Uncle Bill was almost shouting: “Is your radio on? Turn to the news. Pearl Harbor’s been bombed.”

Carl did not fully understand.

“The Japanese have bombed Pearl Harbor,” Uncle Bill said. “That’s ours.”

On 25th Street, Dorothy and Leo also heard the news.

Dorothy, classical pianist that she was, always had Leo tune into the weekly 3 p.m. broadcast of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra on the CBS network. There was one large RCA radio set downstairs, and it wasn’t a bad way to pass a Sunday afternoon while reading the paper and catching up on small talk. That day Arthur Rubinstein was to perform Brahms’s Second Piano Concerto. But as Rubinstein was about to begin, CBS announcer John Charles Daly broke the news of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Said Daly: “The Japanese have attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, by air, President Roosevelt has just announced. The attack also was made on all military and naval activities on the principal island of Oahu.”

After Daly reported for thirty-three minutes, Rubinstein conducted a spontaneous rendition of the “Star-Spangled Banner.”8

Leo and Dorothy knew America was at war. Carl knew that somehow he would be part of it. He just did not know how downright dark and deadly it would be.