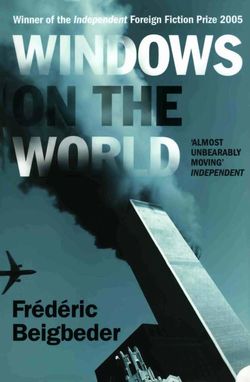

Читать книгу Windows on the World - Frédéric Beigbeder - Страница 10

8:33

ОглавлениеFrom here, the taxis look like yellow ants lost in a gridiron maze. Under the watchful eyes of the Rockefeller family and the supervision of the New York Port Authority, the Twin Towers were imagined by architect Minoru Yamasaki (1912-1982) and Associates with Emery Roth and Sons. Two concrete-and-steel towers 110 stories high. Almost 10,000,000 square feet of office space. Each tower boasts 21,800 windows and 104 elevators. Forty thousand square feet of office space per floor. I know all this because it’s my job in some sense. Inverted catenary of triangular cross-section measuring fifty-four feet at the base and seventeen feet at the apex; footing, 630 feet; steel lattice columns on thirty-nine-inch centers, weight 320,000 tons (of which 13,357 tons is concrete). Cost: $400 million. Winner of the Technological Innovation Prize from the National Building Museum. I would have liked to be an architect; in reality, I’m a realtor. Two hundred and fifty thousand tins of paint a year to maintain. Sixty thousand tons of cooling capacity. Every year, more than two million tourists visit the WTC. Building work on the complex began in 1966 and lasted ten years. Critics quickly dubbed the towers “the Lego blocks” or “David and Nelson.” I don’t dislike them; I like seeing the clouds reflected in them. But there are no clouds today. The kids stuff themselves with pancakes and maple syrup. They fight over the butter. It would have been nice to have had a girl, just to know what it’s like to have a tranquil child, one not permanently in competition with the rest of the universe. The air conditioning is freezing. I’d never get used to it. Here, in the capital of the world, in Windows on the World, a high-class clientele can contemplate the acme of all Western achievement, but they have to freeze their balls off to do it. The air conditioning makes a constant droning noise, a blanket of sound humming like a jet engine with the volume turned down; I find the lack of silence exhausting. In Texas, where I come from, we’re happy to die of heatstroke. We’re used to it. My family is descended from John Adams, the second President of the United States. Great-granddaddy Yorston, a man named William Harben, was the great-grandson of the man who drafted the Declaration of Independence. That’s why I’m a member of the “Sons of the American Revolution” (acronym SAR, as in Son Altesse Royale). Oh yes, we’ve got aristocrats in America. I’m one of them. A lot of Americans boast of being descended from the signatories of the Declaration of Independence. It doesn’t mean anything, but we feel better. Contrary to William Faulkner, the South isn’t just some bunch of violent, alcoholic mental defectives. In New York, I like to ham up my Texas drawl, to say “yup,” instead of “yeah.” I’m every bit as much a snob as the remaining survivors of the European aristocracy. We call them “Eurotrash”: the playboys down at the Au Bar, the lotharios who take pride of place in Marc de Gontaut-Biron’s catalog and the photo section of Paper Magazine. We laugh at them. We yank their chain, but we have our very own, what? American Trash? I’m a redneck, a member of the American Trashcan. But my name isn’t up there with Getty and Guggenheim and Carnegie because instead of buying museums my ancestors pissed everything up the wall.

Pressing their faces up against the glass, the kids try to scare each other.

“Scaredy-cat, scaredy-cat—can’t even look down with your hands behind your back.”

“Wow, this is weird!”

“You’re just chicken!”

I tell them that in 1974, a Frenchman called Philippe Petit, a tightrope walker, illegally stretched a cable between the Twin Towers at exactly this height and walked across in spite of the cold and the wind and the vertigo. “What’s a Frenchman?” the kids ask. I explain that France is a small European country that helped America to free itself from the yoke of English oppression between 1776 and 1783 and that, to show our appreciation, our soldiers liberated them from the Nazis in 1944. (I’m simplifying, obviously, for educational purposes.)

“See over there—the Statue of Liberty? That was a gift to America from France. Okay, it’s a bit kitsch, but it’s the thought that counts.”

The kids don’t give a damn, even though they’re big fans of “French fries” and “French toast.” Right now, I’m more interested in “French kissing” and “French letters.” And The French Connection, with the famous car chase under the L.

Through the Windows on the World, the city stretches out like a huge checkerboard, all the right angles, the perpendicular cubes, the adjoining squares, the intersecting rectangles, the parallel lines, the network of ridges, a whole artificial geometry in gray, black, and white, the avenues taking off like flight paths, the cross streets which look as though they’ve been drawn on with marker, tunnels like red-brick gopher holes; from here, the smear of wet asphalt behind the cleaning trucks looks like the slime left by an aluminum slug on a piece of plywood.