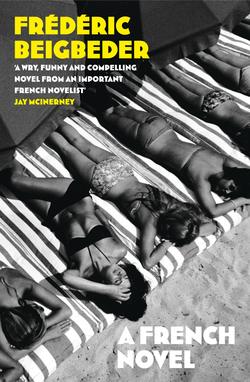

Читать книгу A French Novel - Frédéric Beigbeder - Страница 17

10 WITH FAMILY

ОглавлениеI dreamed of being a free electron, but it is impossible to forever cut all ties with one’s roots. To remember that child on the beach of Guéthary is to acknowledge that I come from somewhere, from a garden, from enchanted grounds, from a meadow that smells of new-mown grass and salt breezes, from a style of cooking redolent of stewed apple and stale bread.

I despise family score-settling, exhibitionistic autobiographies, psychoanalysis masquerading as literature and airing dirty laundry in public. François Mauriac, at the beginning of his Mémoires intérieurs, offers an object lesson in modesty: ‘I will not speak of myself, so as not to oblige myself to speak of you.’ Why do I not have the strength to remain silent? Is it possible to retain a little dignity when seeking to discover who one is and whence one came? I have a feeling that in my quest I will have to embroil many of those closest to me, both living or dead (I have already begun to do so). These people I love who did not ask to be rounded up in a book, as in some police raid. I suppose that every life has as many versions as it has narrators: we each have our own truth; let me make it clear from the outset that this account sets out only my own. In any case, it is not as though I am going to start bitching about my family at the age of forty-two. It so happens that I have no choice: I need to remember in order to grow old. A private detective investigating myself, I reconstruct my past from the scant clues at my disposal. I try not to cheat, but time has shuffled my memories, the way the pack of cards is shuffled before a game of Cluedo. My life is a whodunit in which the balm of memory embellishes by twisting each new piece of evidence.

In principle, every family has a history; but mine was short-lived: my family is composed of people who barely know each other. What is the purpose of a family? To grow apart. A family is the place of non-communication. My father has not spoken to his brother in twenty years. My mother’s side of the family no longer sees my father’s. As children, we see a lot of our family, mostly during holidays. Then parents split up, you see your father less frequently – abracadabra, half the family disappears. You grow up, holidays become less frequent, your mother’s family grow more distant, until you only run into them at weddings, christenings and funerals – no one sends invitations to a divorce. When a nephew’s birthday party or a Christmas dinner is organised, you find some excuse not to turn up: too much fear, the fear that they will see right through you, that you will be observed, criticised, confronted with your failings, recognised for what you are, weighed in the balance. The family brings back memories you had erased, rebukes you for your churlish amnesia. The family is a series of duties, a mob of people who knew you much too young, before you had grown up – and the oldest members are well placed to know that you have still not grown up. For a long time, I thought I could do without it. I was like Fitzgerald’s boat in the last sentence of The Great Gatsby, beating ‘against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past’. In the end, I relived exactly what I had hoped to avoid. My two marriages foundered in indifference. I love my daughter more than anything, but I see her only on alternate weekends. The son of divorced parents, I divorced in turn, precisely because I had an allergy to ‘family life’. Why does that phrase sound to me like a threat, even an oxymoron? It immediately conjures the image of a poor, harried man trying to install a child’s car seat in an oval car. Needless to say, he hasn’t had sex in months. Family life is a series of miserable meals where everyone rehashes the same humiliating anecdotes and hypocritical reflexes, where what you think of as family ties are nothing more than the lottery of birth and the rituals of communal living. A family is a group of people who cannot manage to communicate, and yet loudly interrupt each other, irritate each other, compare children’s exam results and the décor of their homes, and scrabble over their parents’ inheritance while the corpses are still warm. I don’t understand how people can think of family as a place of safety, when in fact it triggers extreme panic. I always believed life began the moment one left one’s family. Only then did we decide to be born. I considered life to be divided into two parts: the first was slavery, and one devoted the second part to attempting to forget the first. Being interested in one’s childhood was for the dodderers and cowards. Having spent so long believing that it was possible to eliminate the past, I genuinely thought that I had managed to do so. Until today.