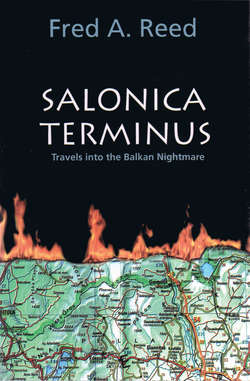

Читать книгу Salonica Terminus - Fred A. Reed - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 1

CITY OF SHADOWS

ОглавлениеDAWN IS BREAKING as the night train from Athens sways and rattles along the northern Aegean shore. Crouched around fires, knots of Albanian refugees look up as it rushes by. Suddenly my fellow passengers begin to rouse themselves, talking excitedly. My eyes follow their pointing fingers. On the northeastern horizon the lights of Salonica glisten, reflected on the still waters of the bay. Time seems to accelerate as the express picks up speed for the long, swooping curve into the place which is to be my home for three months. Forehead pressed against the cold glass of the window I watch the city awaken as the train glides through the rail yard, whistle hooting, then creaks to a stop in the station. Salonica terminus; end of the line. My long journey into the Balkans has begun, a journey of short distances which will lead me deep into history, and carry me across a landscape disfigured by the battle for land and identity.

FROM MY SECOND-FLOOR BALCONY I look on as life unfolds in the tiny square below. Waiters deliver cups of coffee to the season’s last, hard-core outdoor customers at the Café Doré, older men in overcoats, their collars turned up against the wind as leaves from the plane tree flutter to the ground. Nearby, three drunks carefully spread rolls of corrugated cardboard before flopping down on the park benches to snooze in the sunlight. A cat stalks, then attacks and captures a butterfly. A blond-haired young woman dressed in tights and high-heeled boots paces back and forth impatiently, then stalks off. The buzz of small-displacement motorbikes runs like the obbligato of a million wasps over the bass roar of automobiles and buses. Or is the din I hear simply the concentrated conversation of the city, the distillation of one hundred thousand domestic quarrels and coffee-house altercations, market disputes and lapel-tugging street-corner encounters?

My neighborhood is a petrified forest of apartment buildings. Light rarely penetrates to street level, and on weekends when the municipal garbage collection crews are not at work—or during one of their frequent strikes—rubbish rapidly piles up on the sidewalk, drawing hungry cats, stray dogs, and at this proximity to the waterfront, harbor rats. At street level are nightclubs whose patrons are wont to block the narrow sidewalk with their motorcycles and affect an arrogant swagger, their narrowly post-pubescent lady friends a practiced pout.

There is, I learn after a few weeks of residence, a profound consistency about the place. Back in the days before the Café Doré and the apartment buildings, these few square blocks formed one of Salonica’s toughest districts: a place where its rebetiko music milieu lived, performed, fought, occasionally prospered and more often went hungry over cheap wine in makeshift tavernas, or got high in hashish dens. Here was the “Koutsoura” (“the stumps”) of a certain Mr. Delamangas, later to be immortalized in Vassilis Tsitsanis’ late-’40s hit Bakché Ciftliki. In the song, named for a Turkish estate which flourished as a summer bathing spot back when the water was clear, Tsitsanis leads us on a musical excursion, self-referential before such things became fashionable post-modernist devices, through the high spots and the low-down dives of the Salonica shoreline underworld.

Come with me for a whirl out to Bakché Ciftliki My sweet little girl from Thessaloniki . . . Marigo you’ll go crazy when you hear Tsitsani

In Salonica not one, but several layers of the past lie poultice-like, so superposed, so interlocked, their lines of demarcation so blurred that they can hardly be distinguished. The shards of the ancient Macedonian, Roman and Byzantine city lie intermingled, at peace now, with the rubble and the ruin left by Venetians, Ottomans, Sephardic Jews, and Modern Greeks. What is true of historical artifact is true, too, of the mercurial substance of culture, the mist of memory. Adjacent to my neighborhood stood, at some point in its life, a Muslim cemetery of which not a trace remains. This was natural enough, considering its proximity to the White Tower, the main prison which then formed the south-easternmost apex of the city’s walls. Over time the graveyard fell into disuse, and by the late nineteenth century the shoreline around the Tower became the center of passenger and cargo traffic in the harbor, and home to the independent boatmen who plied their craft between the shore and the caïques and steamers anchored offshore. It was a place of constant din, where the cries of the waterfront mingled with the screams of tortured prisoners. With the boatmen came whores, hashish and liquor—the essential components of a mariner’s shore leave. And when the boatmen disappeared with the construction of a modern harbor, the whorehouses and hashish dens stayed on as incubators of rebetiko, hybrid offspring of Turkish and Byzantine musical traditions that expresses, far better than any Greek author with the possible exception of Nikos Kazantzakis, the country’s divided soul.

Tsitsanis, its master, made his home in these mean streets for 17 years, a spectator to the upheavals which wracked Salonica during and after World War II: Nazi occupation, the deportation of the Jews, liberation by the Communist-led guerrillas, civil war and political repression. Rebetiko music was far too subtle to allow itself to become immersed in the contentious political particularities of the moment, though; to speak, as the Greeks elegantly put it, of rope in the house of the hanged. It told, instead, the quotidian stories of people caught in the meat-grinder of social and economic stress; sang of the flight of misery from reality; celebrated the mundane and the commonplace, the carnal and the banal—the better to transfigure them. The more abyssal the sadness evoked, the greater the cathartic effect obtained. Divine intercession of art. “Cloudy Sunday”, Tsitsanis’ four-minute masterpiece of the rebetiko repertoire (and unofficial national anthem of Greece), exudes urban melancholy compounded by the emptiness of that day of the week when, alone, we must endure the company of ourselves:

Cloudy Sunday, how much you’re like my heart Always clouds, nothing but clouds Holy Jesus, Mother of God . . .

Rebetiko music, now squirreled away in tiny basement clubs in Athens where it has been reduced to a diversion for aging purists is still alive and well in Salonica. At the head of my street is a hole-in-the-wall restaurant which serves the neighborhood’s auto mechanics at noon before metamorphosing each night into a place where students and mature couples from what used to be called the working class can rub elbows, quaff cheap resinated wine, and order their favorite songs as they nibble from plates of grilled sausage, spicy meat-balls or lemony joints of roast lamb.

The house act is a guitar-bouzouki (a long-necked relative of the mandolin) duo which performs from a stage consisting of two straw-bottomed chairs shoved up against the wall next to the toilet door. No amplification is necessary in these cramped, resonant confines where tolerance of good-natured intimacy, a forgiving ear and winey nostalgia are the sole criteria for enjoyment. Kostas, the bouzouki player, makes up in enthusiasm what he lacks in pitch, and his enthusiasm is as substantial as it is contagious. But his sideman Theodoris, the guitarist, plays like a man battling for the fundamental values of rhythm and intonation against all but hopeless odds, speeding up or slowing down in an effort to keep pace with his surging, impetuous partner.

Late one midday Theodoris and I strike up an acquaintance. I’m wolfing down a portion of spaghetti in the restaurant after my daily labors in the library of the Institute for Balkan Studies while he and the proprietor discuss arrangements for the evening’s program. Indiscreetly I join the conversation (indiscretion in conversation is the rule in Greece where the most intimate details of your life are soon the stuff of well-meaning banter, clicking tongues and empathetic ‘po po po’s’), my eyes straying to the guitar case resting, resonant with potential, on the table next to mine. His business completed, Theodoris snaps open the case, pulls out his instrument and asks me what I would like to hear. Luxury of an autumn afternoon with no pressing engagements; with no engagements whatsoever. Play me Tsitsanis’ “Beautiful Salonica” . . .

You are the pride of my heart Thessaloniki my beauty, my sweet; I may live with Athens, that beguiler But it’s you I sing for every night . . .

ACROSS THE SQUARE, glaring into my living room, stands the White Tower: the massive, enigmatic cylindrical structure that is the emblem of Salonica. At dawn the sun’s first soft rays give it contour and depth. At noon it stands out in stark, almost one-dimensional relief against the sea and sky. On clear days when the biting north wind the Salonicians call the Vardari whistles down from the Balkans you can see it against the distant peak of Mount Olympus whence the old Gods, driven away by the monotheists, have fled to take up their stations as constellations in the night sky.

And at night, brightly lit by floodlights which obscure those faint constellations, it squats, stocky and self-assured and immovable, as opaque and inscrutable as the history of this darkly ancient town that smells still of the raw concrete that encases memory in an impenetrable shroud. But no matter how thick the concrete, that which it seeks to confine contrives to seep free, to ooze osmotically into the soil and the air.

The White Tower is to Salonica what the Acropolis is to Athens: a concentrated presence that does triple duty as identity, trade mark, and symbol. Like the Acropolis, it is every bit as ambiguous. Perhaps even—as talisman and expression of that most highly prized of contemporary values now that righteous indignation has become risible—ironic. Athenians in their millions file daily beneath the sharply etched rock crowned by the Parthenon, in the inescapable, overbearing shadow of one luminous moment of civilization far greater than their own could ever be. And, height of indignity, the emblem of a civilization since appropriated by the West in its inclusive frenzy to define itself against an Oriental Other of which modern Greece unwillingly partakes.

Here in Salonica, the White Tower functioned for almost five centuries not simply as symbol, but as the thing itself: the palpable material presence of that Other, the Ottoman Empire. But the Ottomans, who ruled the city with what cultivated misconception holds to have been the distillation of tyranny, also—inevitably—infused modern Greece with a repressed Oriental self, a hidden “soul” whose denial, concealment and effacement is the unifying thread of official modern Greek historiography as it attempts to fashion for itself, ex nihilo, a Western identity. For without such an identity, runs contemporary conventional wisdom, there can be no modernity and thus no existence.

The White Tower, say what historians call the sources, was probably built by the Venetians during their brief tour of duty as Salonica’s last Christian masters, before the Turks under Murad II, took the city for good in 1430. Its brutal yet sophisticated stone construction and crenellated battlements resemble nothing else: not the remains of the Byzantine walls nor the surviving Islamic monuments which possess none of its brooding power. Some say that when Sultan Soleiman I, “the Magnificent,” undertook repairs in the mid-sixteenth century, his skilled masons left an inscription which read “Tower of the Lion,” probably in reference to the lion of St. Mark, emblem of the Serenissima Repubblica, which up until then had marked the structure.3

During the early years of the Turkish regime the tower housed the Janissaries, the elite corps which forcibly recruited its members in early adolescence from among the non-Muslim population. But at the beginning of the eighteenth century it was transformed into a prison, and rapidly became known as the “Tower of Blood,” for the tortures and executions which were practiced there. Late in the nineteenth century, on the order of Sultan Abdulhamid II, but at the behest of the Western Powers, it was whitewashed, renamed the White Tower, and relieved of its carceral functions. Irony, did you say? Abdulhamid, the “Red Sultan” whose reputation for brutality went hand in hand with an equally firm resolve to shake up, nay, Westernize, the semi-moribund Empire, ended his reign in ignominy, a prisoner in Salonica, the city he was determined to reconstruct as a window to Europe, the city which was to provide clear proof of Ottoman Turkey’s will and capacity to haul itself into the modern world. It would do this by providing optimum conditions for foreign investment and by guaranteeing human rights. Thus was accelerated a process which could only culminate in the Empire’s destruction; a process that reform, instead of halting, hastened. If it signifies nothing else, the story of Salonica’s White Tower points to the one and sovereign inevitability: the evanescence of the imperial project and the enduring presence of stones.

FIVE MINUTES’ WALK ALONG THE CORNICHE from the White Tower lies Liberty Square, a negative landmark, a place no one visits, where no one strolls, where no one nurses a tiny cup of coffee through the afternoon, where no romantic assignation is ever set. Afflicted with a heroic name, it is the most anti-heroic of places. Liberty Square today is a downtown parking lot and an urban bus terminal, a vital urban space usurped, a place to be avoided, to rush by as quickly as possible, a place upon which the city has turned its back, its canopy of trees the only remnant of its former vocation. The effacement of the square that was once its heart, its window to the world during the turbulent years when Salonica was the metropolis of Ottoman-ruled Macedonia, is a function of an unavowed Modern Greek selective memory syndrome—a condition which dictates that all that does not mesh with the founding myth must be obscured, buried, eliminated, caused to vanish from public historical consciousness. The process need be neither violent nor even conscious, the square reminds us. How better to neutralize a powerfully symbolic space than to transform it into a parking lot, and disguise the act as a case of rogue urban renewal later to be sincerely regretted before “turning the page.” Remove the cars, restore the tree-lined square to its original function? Be serious. In a city which once seriously entertained the notion of an immense subterranean parking garage beneath the corniche, one must not flirt with Utopia. Automobiles invading public space, along with cigarettes whose smoke is forever being blown in your face, are essential components of modern Greek individuality.

King George with his successor Constantine in front of the White Tower, 1912.

From Old Salonica, ©1980, Elias Petropoulos

Liberty Square, Salonica, before the fire of 1917.

From Old Salonica, ©1980, Elias Petropoulos

The greater the haste with which the architects of national identity—or of whatever new verity—seek to expunge discordant evidence from historical consciousness, to excise it from the living urban fabric, the greater the effort to reclaim that evidence must be. In Athens, the rupture with the past has been long consummated. The sole connection with the golden age remains a rhetorical one, preserved by a tissue of museums and green spaces protecting archaeological sites of interest to tourists but ignored by the shop-keepers, civil servants, rentiers and businessmen who populate the city core. Salonica, a vital urban continuum for nearly 2,500 years and a relative latecomer to the leaden influence of national integration, remains fertile terrain for the unmediated archeology of memory.

Liberty Square is not a place to linger. Often I circumnavigate it, and always hastily, on my way to or from the west end of town. Today, lined with bank headquarters on one side, fast-food restaurants and travel agencies on the other, the square which lies hard by the elegant, despairingly silent maritime passenger terminal, owes its name not to some putative liberation of Greek Macedonia. The embarrassment, for Salonica’s masters, is that the Greeks had very little to do with it, except as onlookers.

The name commemorates the short-lived experiment in Ottoman democracy known as the Young Turk revolution which flowered here; celebrates a string of upheavals that catapulted Salonica overnight into the forefront of history. For a millennium it had been the second city of an empire; fleetingly it became the first, though the Empire over which it briefly ruled was already in its death throes.

How majestic our hindsight as we dispose of events which, for the participants, were ripe with the chaos of hope and potentiality. July 24, 1908. From the balcony of the Club de Salonique, the Masonic Lodge overlooking what was then called Olympos Square, Enver Bey, leader of the uprising, proclaimed to a cheering crowd: “There are no longer Bulgars, Greeks, Rumanians, Jews, Mussulmans. We are all brothers beneath the same blue sky. We are all equal, we glory in being Ottoman.”4

Enver’s new constitutional order was to usher in an era of peace, freedom and democracy for the subject peoples of the Ottoman state. But its unavowed intent was to restore the tottering Empire itself. The constitutional order did exist for a few months, before turning, inevitably, into its opposite. Or perhaps, to speak the language of the long ago, far away dialectic, it had carried its negation within it all along.

The Young Turks were the natural ideological offspring of a political and social order which had become increasingly schizophrenic as it confronted the West’s military, social and political superiority. A catastrophic series of military and political defeats were followed by first a subtle, then a violent, penetration of European nationalism into the Balkans. This opened the door to the creation of quasi-independent national states in Serbia and Greece by the end of the third decade of the nineteenth century. The once-immense multinational Ottoman Empire had begun to shrink. Worse yet for Istanbul, the fledgling states were little better than creatures of the Great Powers of Europe, who saw them as useful agents in their war of attrition against the Ottomans. Urgent action was needed to halt the slide. In 1839, Sultan Abdulmejid I launched a series of social, political and economic reforms known as the Tanzimat. For the pro-western forces of the Empire, the evidence was as inescapable as it was overwhelming: Turkey had to modernize or perish. Modernize it would. In the event, it was done in by the cure—a half-willing victim of the New World Order of the day.

The European Powers had dubbed the long, slow collapse of Turkey the Eastern Question. The term euphemistically concealed their aim: to dismantle and redistribute the Empire, particularly its far western and eastern extremities—Macedonia and Mesopotamia—among themselves. The only serious questions, those addressed in back-room negotiations and consigned to secret treaties, were “when?” and “who?” Political and economic divergence among the suitor/rapists gradually became more acute, coming to a peak in August, 1914. The process bore—are we remiss in noticing the forever unclothed emperor?—an uncanny resemblance to the haste with which the European powers and their American cousins now rush to divide the former Yugoslavia and the ex-USSR, fighting the battle for global culture and economic domination to the last Bosnian, Serb or Croat; the last Chechen, Ingush or Tadjik?

The remedy chosen touched off an accelerated decline. By introducing a foreign form of government, under foreign pressure, the Tanzimat threw the country wide open to foreign influence and interference. Foreigners had been given the right to own land in Turkey, and were acquiring positions of control in every branch of the economic and public life of the Empire. To domestic tyranny the men of the Tanzimat had added foreign exploitation.5

No reform, no homeopathic dose of “westernization,” could stem the Ottoman decline. Markets were being globalized in the usual aggressive fashion. Throughout the nineteenth century, the continued erosion of Turkish military power coupled with the Empire’s industrial inferiority combined to set the stage for a full-scale European economic invasion of the Balkans, foreshadowing the lines of battle that would score the peninsula during the First World War. This invasion would take place in Macedonia, core of Istanbul’s European possessions, Salonica’s economic hinterland and key to the prosperity—even the survival—of the regime.

The process was sped along by Turkey’s violent suppression of embryonic Macedonian nationalism. The cruelty of the Ottoman forces had aroused Western public opinion, as malleable then as now, and brought foreign military observers to Macedonia. This combination of crowning indignity and mortal threat to the integrity of the Empire came to a head in early 1908 when Austro-Hungary, which had ruled Bosnia-Herzegovina as a protectorate since the fateful year of 1878, proclaimed its intention to link the Bosnian railway to the Macedonian system, the terminus of which was Salonica. Pan-Germanism was on the ascendancy; the Austro-Prussian Drang nach Osten was but a breath away from becoming reality and Istanbul, gateway to the oil fields of Iraq, was the ultimate prize. Russia, which dreamed of incorporating Tsargrad (as it called Istanbul)—and the Straits, with the promise of access to ice-free seas—into its own expanding Orthodox co-prosperity sphere, immediately responded by announcing construction of a Panslav railway line which would cross the Balkans from East to West, cutting off the Teutonic march to the southeast. The rush for railway expansion along the lines of force of Great Power strategy eerily prefigured the competing north-south and east-west highway and pipeline projects taking shape in the post-communist Balkans today.

Suddenly the port of Salonica had become the focus of conflicting, yet converging, imperial designs. In April, Edward VII and Tsar Nicholas II met at Revel, on the Baltic, where they put the finishing touches to an accord on the pacification program needed to carry out their railway construction program. The scheme was as brilliant as it was disastrous. The Great Powers, caught up in bitter economic competition, would cooperate peacefully to dispossess the Sick Man of Europe. The Turks, as a corollary, would cease to be masters in Macedonia.6

For the better part of two decades dissident intellectuals who had sought refuge in European capitals had been agitating for a the re-establishment of the constitutional order, which they saw as the only way to save the crumbling Turkish state. They called their movement the Committee for Union and Progress, establishing its headquarters in Paris, where they modeled it on the nationalist-revolutionary movements that flourished throughout Europe.

But the Young Turks’ forced march to the balcony overlooking Liberty Square, and thence to Istanbul, only began in earnest when a clandestine group of officers of the Ottoman Third Army Corps in Macedonia—one of whose members was a Salonica native named Mustafa Kemal, later self-baptized as Atatürk, “father of the Turks”—merged with the Union and Progress organization in September 1907. The merger channeled the national humiliation felt by the idealist intellectuals into the day-to-day humiliation faced by the hard-bitten field commanders of the Ottoman army at the hands of overbearing foreign “observers.” To this explosive cocktail was added a groundswell of discontent among the ranks of underpaid and underfed conscripts. The troops of the reformed Empire were now expected to behave like professional soldiers; no longer could pillage be accepted as the army’s chief method of sustaining its men in the field.

In early 1908, insurrection spread like a viral contagion through the Macedonian garrisons of the Third Army Corps, along the very railway lines the Ottomans had built to enable them to transport troops into the hinterland. A full-fledged mutiny was in progress, sped along by the cricket song of the telegraph key and the rhythmic click of wheels on steel rails: the lines of communication had been turned against those who had built them. Emboldened, the mutineers came out into the open. They petitioned Salonica’s European consulates to pressure Istanbul to restore the never-applied constitution. Sultan Adbulhamid scoffed. The revolt spread. By now the revolutionaries had established contact with the city’s Bulgarian, Greek, Rumanian, Armenian and Albanian clandestine organizations. The Jews, Salonica’s largest ethno-religious community, quickly organized a levy to propagate the good tidings throughout the Balkans, as far afield as Sofia and Bucharest.7

Now the sovereign played for time, attempting to forestall the inevitable with the “time dishonored” carrot and stick of bribery and repression. All failed. On July 24, 1908, Hussein Hilmi Pasha, Inspector General of European Turkey and a late convert to the revolutionary cause, proclaimed the Constitution.8

Liberty Square became the focal point of public festivities: Jews, Turks, Greeks, Bulgars, Albanians, Armenians and Levantines fraternized, wept tears of joy and cheered. Forgotten were the blood feuds and deadly rivalries which had transformed the surrounding countryside into a bewildering warren of no-go zones and battlefields. Orthodox popes, rabbis and Muslim imams embraced in public. Brass bands marched and countermarched along the quay, blaring the Marseillaise.

Down from the hills came the guerrilla band leaders: Bulgarian and Macedonian comitajis, Serbian chetajis, Greek andartes. Blood hatreds suddenly dissolved as yesterday’s bandits mingled, hugging and kissing, in the cafés, and were photographed for posterity, their wild beards set off by the cartridge belts criss-crossed over their chests. Sandanski, comrade-in-arms of the martyred Gotse Delchev and one of the most feared of the Bulgaro-Macedonian anarchists/terrorists/freedom fighters, posed in the dignified dark suit of an incipient Father of his Country. The liberation of the subject peoples was at hand. Talk of the old dream of Balkan federation was in the air. Even the town’s Free Masons, who had discretely lent their lodges to the revolutionaries, appeared in public beneath their banners, to the acclaim of a populace in a state of near-rapture. “Long live the Constitution! Long live the Army!” trumpeted souvenir postcards depicting a dashing, rapier-thin Enver Bey. “Liberty, equality, fraternity, justice!” roared the crowd in a Babel of tongues.

To the astonishment of Europe, Salonica overnight became the de facto capital of the Empire, issuing orders, appointing governors, instituting reforms, administering the widespread dominion. Delegations bearing messages of solidarity converged on the city from Greece and Serbia, from Austro-Hungary, from Romania and France. Citizens were suddenly free to speak their minds, to meet in public. The press flourished. But when a delegation from Bulgaria arrived several weeks later, it was welcomed by a shut-down of the city’s coffee-houses and restaurants, including the most prestigious of them all, the Olympus. The Bulgarian government had just declared its intention to free itself of its status as an Ottoman protectorate, upsetting the fragile Balkan equilibrium. The proprietors of the closed establishments were Greek to a man.9

Meanwhile, strikes by workers acting in defense of their class interests had already begun in the heady first days of the revolution under the leadership of the Fédération socialiste, established by radicals who had accompanied the Bulgarian delegation. Salonica, in the first decade of the twentieth century, was not only the second port of the Empire after Izmir, it was Turkey’s largest industrial center, its doorway to European industrial modernity. The propaganda and organizing efforts of the socialists, spurred on by a combative press, rapidly overflowed the small Bulgarian community and took root among the Jews, who formed the majority of the city’s 25,000-strong proletariat, and the Turks. Dozens of strikes broke out, involving longshoremen, bank employees and tobacco workers.

Not only the Greeks, who were the third most numerous population group after the Jews and the Muslim Turks, stood aloof from the growing labor unrest. The Young Turk leadership, which had initially supported the workers, feared that the sudden outburst of industrial activity would scare away the European capitalists who were to revitalize the semi-moribund Empire and transform it into a model of free-market democracy. The situation became even more alarming—from the government’s point of view—when the Fédération sought and was granted affiliation with the International Socialist Federation as sole representative of the Ottoman state.

For decades the ghost of the Fédération haunted the square. During the thirties it was the rallying point for workers’ demonstrations organized by Greece’s militant Communist party. One day in May, 1936, a cortege of strikers set out from Liberty Square led by pallbearers carrying the body of a young worker killed by police. By day’s end ten more strikers had been shot down in the streets. Three months later, on the eve of a nationwide general strike, an army officer called Ioannis Metaxas had declared himself dictator and instituted a fascist regime named for the date—August 4—on which it was proclaimed.

As art stands for the primacy of experience in the world and against the reengineering of the past, so Yannis Ritsos’ “Epitaph” cast the tragic May events in poetic form, as a mother’s lament over the body of her dead son. In the early sixties composer Mikis Theodorakis set Ritsos’ poetry to music, adapting it to the austere, percussive cadences of the rebetiko style.

There you stood at your window And your strong shoulders Hid the sea, the streets below . . .

You were like a helmsman, my son, and the neighborhood was your ship

On another day in May, Liberty Square claimed its last sacrificial victim. Grigoris Lambrakis, a left-wing member of parliament, was killed by a three-wheeled motorcycle in a street just two blocks away after leaving a political meeting. The “accidental” death was quickly proved to have been an assassination plotted by the country’s highest political authorities, and carried out by the same kind of lumpen patriots who, in 1967, scuttled Greece’s fragile democracy and set up the Junta. Today a bronze dove surrounded by upreaching, outstretched hands and identified only by the date—May 22, 1963—marks the place of the crime. While every other statue in Salonica bears a name, the Lambrakis memorial is anonymous. But the sculpture is never without fresh-cut flowers—red carnations, mostly—even on this raw winter evening, as the Vardari, sweeping dust and scraps of oily paper before it, rips down the streets like the scythe of some elemental grim reaper.

LIKE ALL REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENTS, the Young Turks carried within them sharply contradictory objectives, both of which had been latent during the decades of opposition and exile. Those whom we might call liberals favored decentralization, and some degree of autonomy for the Empire’s rich mosaic of religious, linguistic and national minorities. Their adversaries were dedicated to reinforcing the centralizing power of Istanbul, and to Turkish domination. Within less than a year, the Committee of Union and Progress had fallen under the control of the centralizers.10

In their objective, they enjoyed the support of their military allies, whose prime objective had always been to remove the corrupt, incompetent Abdulhamid, and to replace him with a government which would defend the Ottoman state, not liquidate it at discount prices to the Great Powers and their financial backers. The officers were indifferent to ideology. What concerned them was the survival of the institutions they and their fathers had served.11

As with all revolutions, seizing power was the easy part. The Young Turks’ honeymoon was as fleeting as a mayfly’s prime. On the home front, the Islamic Committee of Salonica accused the revolutionaries of atheism, echoing the views of the Caliphate in Istanbul. And as Enver, Talat and their associates slid deeper into the conceptual swamps of Pan-Turkism, the subject peoples of the Empire began to pick up the scent of mortal danger—not only to their prospects for building a multinational state in whose life they could participate as equals, but to their very existence. For what the Committee of Union and Progress had done was to steal a march on its Balkan tormentors. Its new, improved edition of the Ottoman state would apply the same Jacobin nation-state model as they had done, but on a much broader scale, and with all the force and coercive power it could muster. The subject peoples who had rallied to the Young Turk banner—the Armenians in particular—would pay a heavy price for their presumption.

In a speech to a secret conclave of the Salonica Committee of Union and Progress, in 1911, as reported by the acting British Consul in Monastir, Talat Bey declared: “We have made unsuccessful attempts to convert the Ghiaur [Christian Ottoman subjects] into a loyal Osmanli and all such efforts must inevitably fail, as long as the small independent states in the Balkan Peninsula remain in a position to propagate ideas of Separatism among the inhabitants of Macedonia. There can therefore be no question of equality, until we have succeeded in our task of Ottomanizing the Empire . . .”12

International reaction to the events in Salonica was swift and, given the weakness of the Empire’s new, untested, and unconsolidated rulers, crippling. Within four months Greece had declared Crete part of the Kingdom of the Hellenes; formerly docile Albania, long a source of dedicated Ottoman soldiers, was in turmoil; Tsar Ferdinand I had crowned himself ruler of an independent Bulgaria; farther north, Austria-Hungary had annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina. With Bosnia in Austrian hands, the frustrated, landlocked Serbs turned their attention south and westward, toward Macedonia and the ports of the Adriatic littoral, while at the same time plotting revenge against Vienna. Now, as the Ottoman collapse accelerated, national myths were being honed to a razor edge. And where myth became historical necessity, disaster was sure to follow.

Meanwhile, in Istanbul, traditionalist resistance came to a head with a bloody mutiny against the Young Turks by soldiers and theological students in April, 1909. Ten days later, the constitutionalist “Army of Action” from Salonica crushed the insurgents and on April 27, Abdulhamid, the man who had ruled an Empire that stretched from the Adriatic to the Persian Gulf, was officially deposed and sent into exile, replaced by his brother Mehmed Reshad. When his captors informed him of his destination, the “Red Sultan” is said to have fainted. It was to be Salonica.

THE VILLA ALLATINI stands, like a fairy-tale castle nestled in a grove of pines on the eastern outskirts of the city, surrounded by the usual suburban disorder of apartment blocks, gas stations and parking lots. The elegant three-story country estate, designed by architect Vitaliano Poselli for the Allatini family, one of Salonica’s most powerful Jewish industrial and banking clans, is one of a handful of structures to have survived the leveling wrath of the developers.

Here Abdulhamid was dispatched. Along with five wives, several children and a retinue of servants, he lived under house arrest for three years, an object of curiosity for the citizens who, of an evening’s spin in a horse-drawn buggy, might catch a glimpse of the mustachioed old Sultan, red fez atop his head, gazing from the second floor window of the Villa toward Salonica Bay.13

Abdulhamid’s ultimate humiliation came two years later when his brother, now designated Mehmed V, visited Salonica to climax an imperial swing through what the Europeans now called Macedonia. “The population gave their beloved sovereign a reception worthy of the first Constitutional Sultan. Marvelous triumphal arches were erected wherever the monarch was to pass,” rhapsodized journalist Sami Levi, compiler of a lavish photographic album commemorating the royal tour.14

The arches were erected by the city’s principal religious groups—Jews, Muslims, Orthodox (Greek) and Bulgarian, its main industrial establishments which included fez and woolen fabric manufacturing, the Ottoman Tobacco Monopoly, the Light and Power Company, the railways, and the port, as well as several of its most prominent commercial firms: the Café Crystal in Liberty Square, the Splendid Palace Hotel on the quay, and the Au Louvre department store. One of them drew Levi’s admiring attention:

“On the road leading to the city, at the entrance to Union Boulevard, soars an arch of truly monumental aspect. It has been erected by the Ottoman Industrial and Trading Company of Salonica [formerly the Allatini mill and brick works]. Here we behold, in an ingeniously conveyed contrast, the felicitous encounter of Moorish architecture with modern industry. For while the central section of the monument which forms the principal arch, stands against the sky with a silhouette suggestive of the Orient, it is flanked by two huge factory smokestacks creating a most pleasing effect. The harmony of contrasts achieved here, a harmony which a skeptic would have considered impossible, does honor to the architects. Upon the pediment, giving onto the sea-front, is a picture of the mill, on the other side is a picture of the brick works. Both are accompanied by illustrations of the machinery used in the two factories.”15

The diligent Levi could not, of course, dare mention that the dethroned predecessor and elder brother of the beloved sovereign was an involuntary guest in the villa of the Allatini family, owners of those self-same mill and brick-works. For at the conclusion of the imperial visit, “on the following day, Sunday, in the morning, we had the honor of presenting to him a copy of this album. The Caliph deigned to leaf through our work, with which he was well pleased, and which caused him to bestow upon the publisher of the Journal de Salonique, Daout effendi Levy, an imperial gift consisting of a set of diamond cuff-links.”16

The beloved sovereign was, alas, little more than a figurehead; proof that for all their martial bravado, the Young Turks—like all reformers—lacked both confidence and audacity. Their objective had never been to abolish the Empire, but to rescue it. Instead of killing Abdulhamid, they held him as insurance. You never knew what might happen: revolutions are notoriously unpredictable. In the event, the hard-headed imperial dedication of Enver and Talat proved their undoing, and was soon to precipitate Salonica into another maelstrom. In Athens, Sofia and Belgrade the carving knives were being sharpened. London, Paris, Moscow and Vienna watched with ill-concealed glee as their general staffs drew up mobilization plans. If Macedonia was to be the meal, Salonica would be the plat de résistance.

FROM THE SUMMIT OF THE RUE MOUFFETARD, Salonica glimmers in the haze of time and distance, multifaceted, complex and exotic. My vantage point, like a camera obscura of the imagination, is the work room of Elias Petropoulos, a cubbyhole overlooking a tiny Parisian courtyard in the heart of the Cinquiemè Arrondissement. Rebetiko music spills, like plates being tossed in a taverna, from a tape machine wedged in among the books which line the walls from floor to ceiling, overflowing onto chairs and tables. Petropoulos can take credit for almost single-handedly resurrecting this once-scorned genre, turning his formidable talents as a researcher and popularizer to writing down the lyrics of virtually every rebetiko song ever sung. Published in a plump, richly illustrated album, Petropoulos’ compendium set the prim and proper Athenian literary establishment on its ear, and went on to become a perennial best-seller.

Setting the Athenian establishment on its ear has been the cornerstone of Petropoulos’ career. From his twenty year self-exile in Paris—“I’ll never go back, never!” he rumbles, eyes flashing with benign malice—a steady stream of outrageous essays, provocative articles and exasperatingly accurate, often hilarious books has flowed from his prolific pen as celestial retsina might flow from the unquenchable barrels of some cosmic taverna. Subjects embraced astonish in their diversity: Greece’s traditional bean soup, complete with a sophisticated etymological analysis of the various Balkanic and Eastern terms for the common yet extraordinary white kidney bean and its many local variants; the hilarious—and vituperatively condemned—“Good Thief’s Handbook,” which posits the world of second-story men and cat-burglars as a microcosmic metaphor for bourgeois society, with its own rigorous code of behavior and social norms. Academic convention and literary propriety intimidate Petropoulos not in the slightest. He has taken on, with Olympian equanimity, the Piraeus bird market; the ubiquitous kiosque/news-stand/mini-variety store called the periptero; and Greek homosexual slang. But despite the broad range of his work and the hidden sophistication of his method, his approach has always been dictated less by intellectual considerations, more by the roiling viscera. “I’m simply not interested in writing academic books which will be read only by other academics,” he snorts.

Today, pushing seventy, Petropoulos has mellowed slightly. His bushy white beard seems less the avenging prophet’s and more that of the veteran Parisian intello. His manner has become more expansive, perhaps even contemplative as he looks back with affection on the micro-history of his past. Petropoulos’ anecdotes evoke a state of constant temporal flux as they weave back and forth across the decades. The years of absence have pried geographic particulars from his grasp, have liberated names and events from the constraints of linear chronology, but they have produced a limpid essence that has penetrated into every crevice and hollow of his consciousness. Nowhere does this subterranean wellspring of reminiscence flow closer to the surface than when the subject is Salonica in whose teeming streets he quickly learned, as a boy, to identify each national or religious group by its appearance and its speech. “To know who you were,” he says, “you had to know who everyone else was.”

Each could be recognized by the trades and occupations most of its members exercised, a legacy of Ottoman rule. Armenians monopolized the coffee trade; Albanians specialized as butchers; Serbs held the pastry franchise; Thracian Greeks sold milk and yogurt; porters and itinerant tobacco sellers were Jewish. Under the Turks, the Albanians, who enjoyed a reputation for indomitable toughness and devotion to their masters, had been employed as security guards. Their responsibilities included protecting private property, and accompanying children to and from school. Both duties they performed with gusto. Danger, primarily from pederasts as bold as they were numerous, was acute and constant. After the capture of Salonica by the Greeks, the armed guards vanished as the community gradually abandoned its particularities. But a few Albanians stayed on, hawking baklava made with stale bread crumbs instead of the traditional walnuts. As for the pederasts, he laughs, “We kids knew how to resist, and who to stay away from.” Shoemaker’s and tailor’s shops were to be avoided; dry-goods merchants and boatmen given a wide berth.

In Old Salonica each of the main national groups—the Turks, the Greeks, the Jews—had their own fire brigade, which patrolled their respective communities every night, waiting for the cannon high atop the Citadel to sound the alarm. The brigades would likewise fight fires only among their own, he reminisces, slipping effortlessly across the decades. The Turkish firemen had direct connections with the underworld, and would demand payment before unrolling their hoses. In many cases, these brigades—who were little more than organized brigands—would demolish intact houses in order to reach the building in flames. The luckless owners could only avoid disaster at the hands of the fire fighters by paying a handsome on-the-spot ransom. The Jewish brigades, while less given to depredation than their Turkish comrades-in-arms, sang marching songs in Ladino, which featured obscene or insulting refrains in Greek. “Relations between the communities were not necessarily idyllic, even then,” he says with a chuckle. “But that was Salonica. That was its wealth.”

As befitted rulers and administrators, the Turks lived in isolation, their contact with the locals restricted to the barest minimum. The Ottoman system devolved considerable powers to the religious communities whose spiritual and relative administrative autonomy was protected by Islamic law. As rulers and mandatees of God, few learned Ladino, Greek, Bulgarian, Albanian, Armenian or any of the other tongues spoken in Salonica: those supplicants who wished to speak to the Pasha could bring their dragoman. The Turkish overlords would spend their days in idleness, passing time in the city’s many coffee-houses, puffing on water pipes or sipping thick, syrupy coffee from demitasses, relates Petropoulos. “Back then, Salonica was famous for its plane trees, many of whose trunks were so thick that several men had to link arms to encircle them completely. In the summer, under these trees, the Turks would play backgammon. These same trees were also home to enormous bird populations, and it often happened that the backgammon players would be spattered by droppings. But they would keep right on playing, imperturbable, waiting until the foreign material was quite dry before brushing it carefully to the ground. They were the rulers, after all.”

THE RULERS BEQUEATHED TO SALONICA—as they did to all of Greece—a legacy both cultural and material. Extirpating the Ottoman heritage has been one of the central tasks of the fabricators of Greek national consciousness. Proto-Hellenistic language purifiers sought to return Greek to the golden age of Periclean Athens by recreating a modern-day version of the ancient Attic dialect, expunging Turkish, Arabic and Italian words as they went. City planners conspired and acted to Europeanize the Balkan cities they inherited as Greece expanded northward.

The ethno-purist mythifiers were quick to batten onto the Hegelian doctrine of rectilinear progress, recasting it as a kind of Balkan manifest destiny from which, 100 years later, modern-day Greek scholars still seem unable to break free. “Ottoman rule in the Balkans had been identified not only as religious and political oppression” writes University of Thessaloniki professor Alexandra Yerolympou, “but also as economic and social stagnation,” and describes its institutions as obsolete, “relying on juridical distinction of its subjects on the basis of religious affiliation.”17

These judgments seem ironic when we compare the relative harmony in which dozens of ethnic groups coexisted within an Ottoman state where distinctions were made only along religious lines, to the region’s bloody history of ethnic strife between and within tiny states organized on the Western nationalist principle. Or when we reflect on the fate of Salonica’s once-flourishing Jewish community, now reduced by the triple-headed deus ex machina of fire, urban renewal and genocide, to a tiny, fearful remnant.

But to cast the earnest, well-meaning Greek urbanists as first the agents, then the apologists for the destruction of the old city would be to fall too easily into a perverse kind of inverted nationalism. In fact, the progress-doctrine of the nineteenth century had become the main force within the “medieval” Ottoman state as a whole, and had marshaled behind it the prestige and might of expanding colonial Europe. As the Tanzimat of 1839 signaled the political and social westernization of the Empire, so it also sounded the death knell of the medieval city with its dark, fetid, disease-breeding lanes. On imperial order, sections of the Byzantine ramparts which ringed Salonica were demolished. The harbor-side walls were removed in 1870, opening the city to the sea and strengthening its vocation as a crossroads of Balkan trade and the Empire’s gateway to the West. A grid system was introduced, and the former rigid religious divisions were abolished as people of all religious groups were authorized to purchase property and build houses, offices, theaters and restaurants. Salonica, show-window of the Empire, was marching double-time toward its European destiny with the kind of inevitability the latter-day high-priests of Structural Adjustment could recognize, maybe even identify with. The spectacle was as pathetic as it was grandiose.

Istanbul itself had established the precedent. Where once the Empire’s architects were commissioned by the Sultans to build mosques which gave material depth and contour to the Qur’anic dispensation, and in whose beauty the Sultans could accessorily bask, they now turned their talents to lavish sea-front palaces, state structures, and commercial buildings. In both the capital and in its second city the Empire proclaimed to all who could read the signs embodied in these new buildings that Islam, the cement which had held it together for six centuries, had turned frail and brittle, had become irrelevant.

PETROPOULOS SHOWS ME A SKETCH of the Salonica skyline in triptych: at the end of the nineteenth century; shortly after the Greek conquest during the First Balkan War of 1912; and today. The first panel shows a field of minarets, scattered like wild-flowers against a backdrop of hills; the second, rows of low-lying buildings minus the minarets against the same background; the third, a wall of high-rise apartments obliterating the background. The Ottomans’ attempts to transform it into a modern European city reflected the confluence of political power, speculation and high desperation that characterized the Empire’s last days. The project was short-lived: the change of masters amputated Salonica from the Macedonian hinterland, and rapidly reduced it to a bustling provincial town which would have to reinvent itself through the erasure of five centuries, a process some Greeks describe as “awakening from a long nightmare.”

Thus Salonica’s fleeting glory as the bridgehead of Ottoman modernity met its brutal end in early November, 1912, when the Greek army led by the Glucksbergs, père et fils—King George I and Crown Prince Constantine—entered the city in a driving rain. Symbolically, their route followed the Via Egnatia and beneath the triumphal arch of Galerius, in the footsteps of the legions of Rome and Byzantium. Popular acclaim was less than delirious; the occasion well short of triumphant. As the bandy-legged, unshaven, dark-skinned, mud-spattered infantrymen marched through the heart of the commercial district led by their mounted officers they encountered not happy throngs but indifference, locked shops and closed shutters. Small knots of enthusiastic Greeks looked on, of course, cheering and waving Greek flags. But the majority, the Jews, not only considered themselves loyal Ottoman citizens; they remembered how they had celebrated the victory of 1897, which had seen Turkish armies humiliate the Greeks and thrust far south into Greece. They remembered, too, that the Sultan had given them a new home more than four centuries before when a Christian monarch had expelled them from Spain. “The Greeks claim they liberated Salonica,” snorts Petropoulos. “But exactly whom did they liberate?”

The putative liberators of Salonica may have had more on their minds than the release from bondage of their unredeemed brethren, for the city’s Greek minority was relatively small. The first census carried out by the occupation authorities, in 1913, showed 61,439 Jews, 45,867 Turks, 39,956 Greeks, 6,263 Bulgars and nearly 5,000 of diverse other nationalities.18 As interpretation of census figures in defense of national interests has provided much of the ammunition for Balkan bloodshed, extreme caution must be employed in their use. The most reliable rule of thumb is to consider all ethnic-based census reports as flawed and suspect. The problem is, that in this region, there are none other.

Greece, in the first three decades of the twentieth century, was in the throes of the Megali Idea (the “Great Idea”) an aggressive strategy of national expansion designed to “restore” the Byzantine Empire and establish the capital of Greece in Constantinople. If this meant removing the infidel Turks, and blocking the equally exalted national aspirations of the Balkan states to the north, so be it. Athenian intellectuals dreamed of a Greece of “five seas and two continents,” while Greek military intelligence officers disguised as consular officials subverted the previously law-abiding minority communities scattered throughout the faltering Ottoman state. As the greater subversion of Ottoman Turkey was the principal aim of the Great Powers, they found it useful to flatter Athens’ megalomaniac aspirations, now letting the horse gallop ahead, now reining it in, to suit their own political and geostrategic designs.

King George was to pay the ultimate price for his ostentatious public support of Hellenic nationalism. Instead of retiring to the safety of the royal palace in the countryside near Athens, he chose to stay on in Salonica. The desire to calm increasingly vociferous anti-monarchical sentiments directed against the German-Danish royal family by the pro-British republican faction led by an ambitious Cretan politician called Eleftherios Venizelos may also have been a consideration. The King was wont to stroll unguarded through the streets, a living demonstration as much of his concern for the realm’s newly acquired subjects as of his foolhardiness. On one such constitutional, in early March, 1913, he was shot and killed on a quiet street in the eastern suburbs by a lone gunman, a Greek. The alleged killer, a mental defective, was said to have killed himself—conveniently—shortly after his arrest.

Crown Prince Constantine, liberator of Salonica and victor over the Turks, quickly ascended the throne. Unlike his cautious, diplomatically-minded father, the blustering, headstrong but mental light-weight Constantine fancied himself as a Supreme Commander. He was also an ardent Germanophile, who affected the spiked Prussian helmet as he participated in military exercises with his friends of the imperial German general staff. No one had failed to notice that King George had enjoyed close relations with the Entente, one member of which, France, had trained and equipped the victorious Greek army. Greek historians, asserts Petropoulos, have handled the assassination with an uncustomary lack of curiosity. Though no links between the killer and the pro-German lobby in Greece have ever been established, the regicide poisoned Greek domestic and foreign politics for decades, pitting the pro-German royalist faction against the pro-British supporters of Venizelos.

Nowadays Greece is a republic, of course, though the playboy grandson of the King, former heir apparent Constantine Glücksberg, still flirts with posing as a national unifier for a populace increasingly disgruntled with the cupidity of elected politicians, a concept copied from dusty British and American Cold War manuals. In the modishly nondescript Euro-capital, Athens, royalty has vanished both as memory and concept. In parochial Salonica, however, both monarchs still linger on in statue form. George I, the father, slumbers in leafy, marbled obscurity, remembered in a bust set in a mini-park marking the spot where he was shot, surrounded today by the indifference of pizza parlors, ice-cream shops and green-grocers. But Constantine the son, he of martial mien, can be seen astride his war-horse on the southern flank of Vardar Square. It was not always, however, thus.

For years, the monarch’s equestrian statue—Salonica’s marble horseman which has inspired, as far as I know, no local Pushkin—was hidden shamefully away in an obscure square named for the pre-war fascist dictator Metaxas. But during what the Greeks now call “the miserable seven years” of the Junta, the statue was installed at the foot of the Via Egnatia where it stands today, torso facing due eastward toward Constantinople, ultimate goal of Greek national fantasy, head turned harborward, toward the red-light district.

GREECE WAS NOT ALONE, of course, in pursuing an expansionist national policy. Its Balkan neighbors were assiduously pressing their own claims to all, or a portion, of European Turkey, at the heart of which lay Macedonia. Bulgaria, which had been brief master of most of the territory following Istanbul’s defeat in the 1877 Russo-Turkish war, had never abandoned its claim. Serbian extremists, stung by the Austrian occupation of Bosnia, founded an organization called “Black Hand” which was to provide exemplary leadership in the sacred struggle for Greater Serbia.

By early 1912, Austrian designs on the Balkans had become unmistakable. Serbia and Bulgaria, under Russian patronage, joined forces to block Austro-German expansion toward the Adriatic and the Aegean. A month later Greece and Bulgaria entered into a defensive alliance. The Russian scheme was a brilliant success. So brilliant that its creature, the Balkan League, soon began to act as though it had its own agenda. In the event, it did: the military defeat of Turkey and the partition of Macedonia.

In early October, Moscow and Vienna, those erstwhile adversaries, warned their Balkan protégés against precisely such a temptation. The warning came too late; the puppet had taken on a life of its own, had slipped its strings, and now acted independently of the puppet-master. Montenegro, the smallest of the allied states, declared war on Turkey. Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece followed suit. Forced to wage war on three fronts, the Ottomans hastily fell back towards Istanbul. The rapidity and completeness of the allied victories astonished their European patrons, and shattered what remained of Turkey’s European dominions.19

For Greece, the Balkan campaign was sweet revenge for the humiliating defeat of 1897. The Greek forces bore north, sweeping away the Turkish army or surrounding and isolating its garrisons. Soon the road to Salonica, which lead through the marshy delta of the Vardar, lay open.

W. H. Crawford Price, a British journalist who could ill-conceal his sympathies for the doughty Hellenes, was an eyewitness to events in the Macedonian capital: “We were cut off from all communication with the outside world, and surrounded by hostile armies. At Yenidje there were Greeks, at Kuprili (Veles) Servians, at Strumnitza and Demi Hissar Bulgarians, while outside the range of the guns at Karaburun lay the Greek fleet, eager to rush in and seize its impotent prey. Provisions were at famine prices; wise housewives had laid in stores of flour; Consulates had made necessary arrangements for sheltering terrified subjects. Greeks were exultant but terrified; Jews downcast and fearful for their worldly possessions; Turks broken-spirited but stoical; Europeans indifferent but anxious.”

“In the cold, muddied streets men wandered aimlessly hither and thither, discussing the eternal ‘situation’ in entire ignorance of fact or details.”20

The citizens of Salonica, obsessed with the question of day-to-day survival, paid little heed to the Empire collapsing about them. Turkish refugees fleeing before the invading armies sought shelter in the city. The first arrivals were housed in mosques and schools, but their number soon exceeded available space. It was not until the evening of October 29, 1912, when the German patrol boat “Lorelei” dropped anchor in the port that the Salonicians realized they would be losing their most illustrious guest, deposed Sultan Adbulhamid. Within a few hours the recluse of the Villa Allatini and his retinue had been transferred to the warship, which promptly steamed off toward Istanbul. The last thing the crumbling Young Turk regime could afford was the loss of the erstwhile “Red Sultan,” its prize hostage and nemesis. He died in 1918, a lonely pariah, in the capital on the Bosphorus, a few months before the final defeat which sealed the fate of the Empire.

Meanwhile, the military situation continued to deteriorate. Greek forces were now within striking distance, and a Bulgarian army was rushing south toward Salonica in a forced march. The garrison could not withstand a siege; the Turks decided to capitulate. On November 8, Hassan Tahsin Pasha, the Ottoman commander, accepted terms which had been handed him the previous day. That evening, the indefatigable Crawford Price proceeded to the Konak, the government house: “I found Nazim Pasha, the Governor General, sitting on a divan with his legs curled up under him, calmly writing his last letter as Vali of Salonica. His nation had lost its reputation; Islam had been driven out from Macedonia, and he had lost his post; but he nevertheless sat there serene and apparently unaffected by the tremendous history in the making around him.”21

Thus, with a whimper, ended 482 years of Turkish rule. The government house they built still stands. Its creaking wood floors no longer echo with the shuffling of Ottoman functionaries’ slippered feet, but every morning supplicants arrive, congregating around sub-ministerial doorways, petitions and letters of recommendation in hand. Fine Persian rugs cover the floor of the Minister’s office, not unlike those the Greeks found when they seized the Konak the following day.

A new, official victory parade was organized three days later after the occupation authorities had ordered all homes and shops to fly Greek flags. In the interim, the symbol makers had been hard at work. The capture of Salonica was decreed to have taken place on Saint Demetrius’ day, October 26, a date calculated to make the hearts of the Greek citizens beat faster. Had not Salonica’s Byzantine warrior patron, astride his red stallion, intervened miraculously in the past to save the metropolis? But in 1912, the old calendar was still in force in the Orthodox Church. Saint Demetrius’ day had been celebrated two weeks before.

The occupiers took rapid action to change the face of Old Salonica. The process of Hellenization was relentless, thoroughgoing and even violent. Its first victims were, of course, the Turks. The city was quickly stripped of the primary symbol of its former identity. Virtually all of Salonica’s 60 minarets were destroyed during the first five years of the Greek occupation, explains Petropoulos. The Greek military waged its own kulturkampf. Aided by Prime Minister Venizelos’ much-loathed Cretan gendarmes, it obliterated signs in French and Spanish. Mosques were transformed into churches, as shown in post-cards of the day, guarded by armed Greek soldiers to discourage the Muslim faithful from attending to their religious duties. One minaret was left standing, at the Hortac Effendi mosque, the late-Roman circular structure known as the Rotonda. The municipal authorities attempted to destroy it too, on the pretext of imminent collapse, Petropoulos relates. “But minarets have a bad habit of not falling, even in the most powerful earthquakes. They’re built to sway, not break.”

For Salonica, the crucial question was that of Bulgaria’s claim to the city. A few hours after the Greek forces had marched into the city along the coast road from the west, a Bulgarian army detachment had entered from the north. They immediately seized the former mosque of Saint Sofia, now reverted to an Orthodox cathedral, set up their military headquarters just across the street, and organized their own victory parade, complete with brass band.

“The Greeks found themselves preoccupied,” wrote Crawford Price, “with the serious complications presented by the disconcerting behavior of the Bulgarians. They had become the unwilling hosts of ten instead of two battalions of allied troops; several public buildings and one of the largest mosques had been commandeered by the Bulgars; General Theodoroff had hastened to inform the King and the whole world that the Bulgarians had conquered the town. Moreover, Sandanski’s ‘komitadjis’ had entered the citadel.”22

The victorious allies—armed, trained and abetted by their Great Power sponsors—had all but succeeded in ousting the Turks from Europe. Now dissension grew in their ranks as among robbers arguing over the division of the spoils. To complicate matters further, the Great Powers were insisting that an autonomous Albanian state be created from the wreckage of European Turkey, which meant that the Serbs would have to give over to the new state some territory they had conquered. To turmoil was added opaque complexity.

In an atmosphere of claim and counter claim, Greece and Serbia concluded a secret alliance against their erstwhile ally Bulgaria. At this point the Bulgarians made yet another of the fatal blunders which have plagued the country’s foreign policy. In late June, 1913, they attacked the Greek and Serbian lines in Macedonia. The move was intended as a political demonstration the aim of which was to provoke Russian mediation. But the Serbians and the Greeks replied to the Bulgarian “demonstration” with an energetic counter-demonstration of their own: they declared war. Once again Balkan peasants were handed rifles, given a fistful of bread and onions, and sent off to fertilize the Sacred Soil of the Nation with their blood, torn flesh and crushed bones. As they may yet do again if the secret Balkan deals we can assume are being made today are acted upon.

In Salonica, the Greeks swung into action immediately. The Bulgarian army had established small garrisons in half a dozen quarters of the town, and around each the Greeks had placed strong detachments of troops, thus rendering escape impossible, writes Crawford Price. “Against the principal Bulgarian stronghold . . . the Greeks showered bullets from the houses opposite, while from quick-firing guns posted on top of the famous White Tower, a murderous leaden hail swept up the street at given intervals.23

The Second Balkan War was short, intense and bloody. And though it was militarily decisive, it created an even greater political impasse than the one which had caused it. Surrounded, under attack from all sides, Bulgaria could offer no serious resistance to the coalition of Greek, Serbian, Rumanian and Ottoman forces. On August 10 peace was signed by the Balkan states at Bucharest. Greece was awarded Salonica. Bulgaria not only lost the city, but its territorial gains in Macedonia as well. Greater Bulgaria overnight became an irredentist’s folly. The Bucharest treaty solved nothing: Bulgaria refused to accept the settlement; Serbia still chafed at Austria’s occupation of Bosnia. The stage was set for the Third Round, which was to begin one year later, when Archduke Francis Ferdinand visited Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, St. Virus’ day, anniversary of the battle of Kosovo Polje, in 1389.

A HISTORIAN HAS APTLY DESCRIBED the Balkan crisis as causing “the spark that set off the fatal blast in the powder keg of Europe.”24 Salonica, which had been the apple of discord throughout the long agony of the Ottoman Empire, remained a ring-side spectator to the hostilities as Greece declared neutrality at the beginning of the First World War. This ill-suited the Entente powers, which attempted to entice Athens to enter the war on their side with promises of territory in Asia Minor in return for concessions to Bulgaria in Macedonia, thus laying the groundwork for another disaster. Venizelos, Great Statesman on the make, rose to the bait like a hungry carp. But the court and its pro-German friends in the armed forces favored the Central Powers and refused to take any action which might offend the Kaiser. Stalemate ensued.

A small French-British expeditionary force was promptly dispatched to Salonica under the pretext of honoring the Entente’s treaty obligations to Serbia. The allies landed in October, 1915, at Karaburun, a promontory east of the city not far from Batche Ciftlik, and thus began a de facto military occupation/blockade which was to last until Greece finally agreed to join the war against the Central Powers.

Once more the cafés of Liberty Square hummed with the cosmopolitan confusion of tongues as French and English vied with Greek and Italian. Ladino, too, was never far out of earshot. The polylingual brothels of Vardar Square did ravishing business. For lack of military diversion, Generalissimo Paul Sarrail, the aging supreme commander of the allied forces, spent most of his time organizing glittering soirées the main attraction of which was his young and voluptuous bride, prompting French Prime Minister Clémenceau to remark that Sarrail had two fronts to defend.25

Into the morass of a city surrealistically aloof from combat while caught up in swirling, intertwining currents of intrigue, sailed a modern-day Argonautin-reverse. Alberto Savinio, younger brother of painter Giorgio De Chirico, had set out from Taranto aboard the troop-ship Savoia, a member of the Italian contingent of the Entente forces. Their final destination was Salonica.

We arrive at our goal. The sun rises above Mount Athos. I look to the left: from the middle of a boiling ridge of clouds the white wedge of Olympus opens out. Jove sleeps up there amidst the snow and the cries of lice infested eagles: ex-god, with thundering eyebrows who clasps Ganymede in his arms, tender little sacerdote of mystic pederasty. And look down there, another world: it’s Salonica, which I nickname ‘the disquieting city’. . .”26

Savinio’s vision of the Orient as represented by Salonica may have been a response to the Grecophile proclivities of his more gifted elder brother, an orientalizing counter-vision, a proto-Nietzschean parody or the congenital envy-tinged scorn we reserve for those who are almost identical to us. Something of each, probably. Savinio is nothing if not the ambiguous counterweight to the classicist de Chirico, who assimilated and later metaphorically depicted the mechanisms (including those of the engineer and the earth measurer) by which Europe had managed to appropriate ancient Greece while conjuring up a “Greece” of the imagination on the site of a former Byzantine outpost and Ottoman province. To call our visitor jaundiced would be to understate the matter:

I’ve even had to give up the little bourgeois diversion of reading the newspapers. I don’t have the courage to barter away half my pay for one of those smart, hybrid multilingual sheets that tell me ‘Luna di Moisè Molho and Guida Bejà Matarasso are fiancés’ or ‘Maison Saporta met en vent des articles militaires à prix très réduits . . .’ Then there’s the night life: ‘The White Tower’ and the little shack called the ‘Variétés’ where a Corinthian songwriter sings ‘The Lover’s Deaf in the Neapolitan dialect . . . Oh, my far away friends, I have dreams, so many dreams (. . .)

August. Half of Salonica burns in a single night. A bit of relief from the mattress of monotony. But the fire’s put out and my relief with it. 27

What had succeeded only in stirring the semi-catatonic Savinio from his lethargy was, for Salonica, a monstrous convergence of disaster and opportunity: the Great Fire of August 5, 1917. Kindled in a tiny shack just north of Saint Demetrius Street, and fanned by hot winds, the blaze quickly engulfed the wood-framed constructions that made up most of Salonica’s central district. Under orders from General Sarrail, the French forces bombarded the city to stop the fire from spreading, thereby encouraging its ravages. By the time it hand finally burnt itself out, 72,000 people were homeless, and more than 4,000 buildings had been destroyed. Gone were the cosmopolitan cafés and the great sea-front hotels, the department stores and hundreds of small craftsmen’s shops. More tragically, the fire obliterated the infrastructure of the Jewish community, its synagogues and schools; most of the buildings lost had been owned by Jews. All that had given the city its distinctive flavor now lay in smoldering ruins.

The Venizelos government, which had begun as an anti-monarchist military rebellion in Salonica the preceding year, promptly expropriated the burned-out area, and appointed an international commission chaired by Ernest Hébrard, a French city-planner serving in the Army of the Orient, to supervise the transformation from a Jewish-Ottoman city to a Helleno-European one. Hébrard, who was later to gain higher distinction for his remake of French colonial Hanoi, devised a uniform architectural style, opened wide boulevards and diagonal transverse avenues in the manner of Baron Hausmann. The memory of the city was to be embodied—embalmed, better—in “noble” buildings harking back to the Roman and Byzantine past.28 The plan, needless to say, expressed the prevailing ideology of the day: modern Greece as the reincarnation of Byzantine imperial glory, somehow combined with the democratic heritage of the Athenian Golden Age and seasoned with a liberal pinch of Alexander the Great. What the fire had not obliterated, Hébrard’s plan would. The remaining vestiges of the Ottoman Empire, and the muscle and sinew of the Jewish community which for four centuries had given Salonica its inimitable character and its life, were swept away.

Map of Salonica from Karl Baedeker’s guide (1914).

From Old Salonica, ©1980, Elias Petropoulos