Читать книгу Truth, Lies and Alibis - Fred Bridgland - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеThe ultimate truth is that history ought to consist only of the anecdotes of the little people who are caught up in it.

Louis de Bernières1

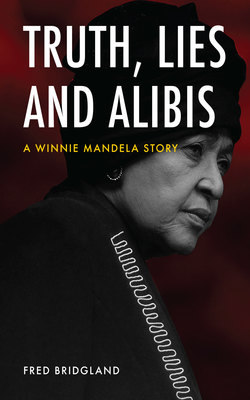

Two disturbing events within a short time of each other in southern Africa a quarter-century ago shaped my life and thinking for ever. To a significant extent, they laid the ground work for this book, Truth, Lies and Alibis: A Winnie Mandela Story.

First, my closest friend in Angola, Tito Chingunji, a fine man by any standards, was murdered on the orders of Jonas Savimbi, leader of the Angolan guerrilla movement UNITA (the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola).

Tito and his brother-in-law Wilson dos Santos, another popular young underground soldier, were taken by General Cami Pena, Savimbi’s nephew, to a forest glade where an execution squad bludgeoned them to death with rifle butts.

Tito’s wife, Raquel, was also beaten to death. Tito, UNITA’s foreign secretary, and Raquel had five children, including twin boys, Katimba and Jonatão, not yet a year old. All five children were picked up by their legs and their heads were swung against tree trunks until they were smashed and lifeless.

Other members of the Chingunji family, including Tito’s mother and father, were executed. His mother was tethered by a tow rope to a truck and dragged through the bush until she was dead.

The hideous slaughter went on. By the time it finished there was not a single Chingunji left alive in Savimbi’s territory. In all, an estimated fifty members of the family died. I received death threats and a member of my family was threatened with mutilation.2

The reasons behind these and other killings ordered by Savimbi are bizarre and complex: they include wild allegations of witchcraft, sexual jealousies and power paranoia. They are the subject of a part-completed new book by myself.

Savimbi lied, lied and lied again. He told people, including governments that provided his movement with help, that Tito was alive long after he had been killed. He even wrote to US Secretary of State James Baker alleging that I had plotted, in collaboration with a young Angolan woman and “junior members of the CIA”, to assassinate him using the powdered remains of a chameleon!

Tito and I had gone through tough times together in the course of the long war in Angola: he had become much loved by my family on visits to our homes in Edinburgh and London. So his murder and those of his own family came as an immense shock to me, the sheer, mad, destructive, cruel wastefulness of it. I quickly knew the meaning of bereavement, a wrenching, terrible deprivation of a friendship that had endured difficulties and had, I hoped, many rich years to run. All my efforts and subterfuges to save his life failed. His end must have been as lonely as Steve Biko’s: his life had been snuffed out with much the same callousness. I found myself lying awake at night wanting to reach out to him in his unmarked grave and hug him and tell him he was loved and that in some scheme of things his efforts and suffering had real meaning. I miss him and his kind and wise manner to this day.

****

It was against this traumatic background that in the same year, 1991, I began reporting for my newspapers – the London Sunday Telegraph and The Scotsman, then Scotland’s national newspaper – on the trial in Johannesburg of Mrs Winnie Mandela on charges of kidnapping and assaulting a 14-year-old boy, Stompie Moeketsi Seipei (from now referred to simply as Stompie Moeketsi).

I was approached at the time by a British publisher to write a biography of Mrs Mandela. I declined. I had no “inside information” or special insights to share, only “facts” out in the public arena that were common knowledge.

However, when witnesses and co-accuseds in the trial began disappearing, with police apparently doing little to find them, and as lawyers began to advance unlikely alibis, all my internal warning bells began to clang loud. It all reminded me of the steep Tito–Savimbi learning curve, although the two cases were not precisely comparable.

And then, a few months later in that same year, I found in Zambia, with a bit of journalistic initiative and a big slice of luck, a youth who had been dubbed the “missing witness” from Mrs Mandela’s trial. He had been abducted from South Africa by an African National Congress Special Operations Unit and imprisoned in Zambia without charge or trial by that country’s President, Kenneth Kaunda. With the help of Kaunda’s successor as Zambian head of state, Frederick Chiluba, and a British MP, the “missing witness”, Katiza Cebekhulu, was freed from prison and I conducted long interviews with him in Britain and Sierra Leone. His story, repeated many times since then, was that he had watched Mrs Mandela stab Stompie Moeketsi to death and that she was responsible for other murders, including that of her own medical doctor.

Having listened to Cebekhulu’s story, I finally agreed to write a book about Winnie Mandela. Here was an account in which the apparent truth was more dramatic than fiction. I also wrote and narrated an hour-long BBC television documentary – based on the book – in which Kaunda admitted imprisoning Cebekhulu at Nelson Mandela’s request to make sure that he was unable to give evidence in Mrs Mandela’s trial.

The Winnie book3 took the story only up to mid-1997, before Mrs Mandela was subpoenaed to appear before a special Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearing into the activities of her notorious bodyguard, the Mandela United Football Club. It left innumerable questions unanswered.

After a career in journalism across four continents, I found I had grown more concerned with the stories of “little” and “unimportant” people rather than those about the rich, famous and high-ranking living in their self-important bubbles. Many “little” people died on Savimbi’s commands. And in the Winnie Mandela saga “little” people suffered appallingly, both at her hand and as a result of the shortcomings of the police and justice systems. Laws, after all, are spider webs through which the big flies pass and the little ones get caught.

Over the years many of these “unimportant” people helped and trusted me: their stories, I believe, deserve to be told. It is the only way I can repay most of them. This book, despite its title, is more for and about them than about Mrs Mandela, who died as the work was being completed. I also believe that new, younger generations need to know and try to understand the full story.4