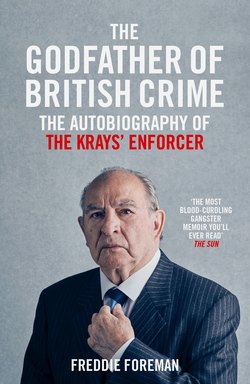

Читать книгу Freddie Foreman - The Godfather of British Crime - Freddie Foreman - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE JUMP-UP

ОглавлениеI’m moving on too quickly here. Let me go back and tell you of my teenage years at Wandsworth Road, which were amongst the happiest of my life. At 18, while still living at my mum’s, I became a full-time thief. My social life was exciting and fulfilling and I was fit and ready to take on the world.

My mates Lennie and Patsy loved staying at my place, mainly because my house was the general meeting place and also local girls joined us for sexual adventures in the drying rooms at the top of the block. We used to hang around the entrance to the flats late at night while Rosie, one of the girls I fancied, would come by. I’d greet her and offer to escort her home. Of course, there was a diversion. A gentle tug on the arm would be enough to change direction and I’d lead her up to the drying rooms. Her protests were never meant to carry much weight and we’d soon be at it with a knee-trembler against the wall. Lennie used to tail me off minutes afterwards. The routine was: handkerchief out of the pocket, wave it so Lennie could see, and give a little cough to signal the changeover. Rosie would act startled: ‘Who’s that?’ I’d tell her it was my mate Lennie and, a little indignantly, she’d threaten to go home. But the thrill of a further sexual adventure was too strong and she stayed. Lennie would slip up behind and take over from where I’d left off. This became a right regular occurrence.

On another note, I was still worried about my George’s health shovelling coal and breathing in all that dust in the barges. Even though he was older than me, I suggested he pack the job in and join my little firm. ‘You’ll be dead in five years if you don’t,’ I warned him. The pollution outside the power station was bad enough. A fine layer of coal dust covered the roads and footpaths, so when you walked down Nine Elms Lane to the power station you left a trail of footprints. I couldn’t bear to think what this did to my George’s lungs and reckoned his chances of survival would be better with me. In those days these was no social security, so you only had two choices: to work or to thieve. I thought thieving was the lesser of two evils.

After working with the Forty Thieves, I progressed to the jump-up. This involved stealing the goods from a commercial traveller’s car or from a lorry and driving them to an arranged meet where they were loaded into another van and sold on my behalf. I bought a five-hundredweight Ford van and, through trial and error, taught myself to drive it. Driving licences were provided by a friend in County Hall.

Just after the war there was good money to be made from the black market in rationed goods. The profits were better still if you didn’t have to pay for the rations in the first place. The canteen at George’s power station catered for hundreds of people and was given a large allocation of tea, which was very much in demand. Every three or four months they would get eight or nine chests, some of which would probably go to other canteens. You could get double the price for it on the black market, so I decided we had to have it and asked Lennie and George to help. We broke into the building one night, made our way to the canteen and got the tea chests out without any problem. It was a good night’s work.

The night watchman was alerted to us, but it was nothing to tie him up, the work of only a few minutes. Much better than battering him unconscious. People are normally so surprised and shocked by a sudden hold-up or threat that they freeze and are easily subdued. George said he earned more from that night than working for several months at the gasworks, and that convinced him to turn his job in and join me. Soon we had organised people in different factories to sell our bits of gear to their large workforces, and people began approaching us with orders for items in demand. I was always being asked for spare lorry wheels with plenty of meat on the tyres. They came to between £10 and £20 each, which was a lot of money then. We stored the tyres in George’s house in Wickersley Road – until we broke the floorboards bouncing tyres into the backyard. The final straw came when we broke the staircase. George’s Rita was not amused.

We used to nick anything and everything. We’d follow a travelling salesman and, as soon as he went into the house selling goods on the never-never, the jump-up would happen. You’d use a screwdriver to open the quarterlight window of his motor, up went the catch, open the door, start the car up with a flat key and drive off. Lenny or George would follow in our van to a quiet street, preferably a cul-de-sac with a wall on either side, load up the gear and leave the salesman’s motor there.

We got plenty of Twining’s vans loaded with tea chests and a couple of drivers even let us have all their goods by parking up outside a café. While they were having a cup of tea we’d jump up and drive it away. Some drivers would even approach us and ask if we’d rob them for a percentage of the take. One of my relations offered to let us have his truck, which we ‘nicked’ from him at the Lyons Corner House by the Tower of London. Offers were coming our way all the time.

If we sold our goods at factories, we’d have to wait until the end of the week before we got our money. This became a bit of a hassle, so we found a buyer in Chelsea who stored the gear in a garage adjoining a vicarage. We first met Fatty Sid the Yid in the local pub and he gave us an address to deliver our goods. We said we would bring a van full of clothing the next day at about 2pm. ‘I’ll be on the corner waiting for you,’ he told us.

We drove there as arranged, only to see the old vicar standing on the corner. I went around the block again hoping he’d go away, but he was still standing there with Sid the Yid at his side, gesticulating and mouthing, ‘Come on!’ I refused to drop off the clothes, pointing at the vicar. ‘Don’t worry about him, it’s the vicar’s garage! He’ll be in for a pair of grey flannels in a minute.’ After that, Fatty bought all our gear from us in bulk.

The jump-ups improved as time went on. You progressed to lorryloads of tea, cigarettes and cloth, and buyers from all over London started to spring up. You could sell anything then, and people would place orders for the next time you got a load. Nobody grassed you up in those days – they would rather buy something cheap.

Mum was getting a little worried about my activities, though. Even when I was working for Pannet and Eden I would tell her to help herself to my wage packets if ever she was in need of money. She would open the wardrobe and find £50 in notes and all my wage packets unopened. Once she found a .45 revolver stuffed at the back of the drawer: ‘Oh, you do worry me, Fred,’ she told me once, though she never brought the subject up again.

My father knew I was thieving, but never talked about it. He was grafting as a taxi driver by then. He’d done his ‘knowledge’ – on a bicycle, learning all the shortcuts along the back streets of London. The hansom cab he drove had no sides or protection from the weather and, like many drivers, he finished up with rheumatism in the elbows and joints. Years later, in his late seventies, he had to have plastic replacement elbow joints fitted. He’d suffered badly.

George and I would take our goods to various markets where we had contacts. But, with a busy schedule, I was seeing less and less of Patsy Toomey, who worked in Covent Garden. Patsy had always been very possessive of our friendship and was now becoming unreasonably jealous. He wanted to be in on the action and felt he wasn’t, even though we’d given him gear to off-load on our behalf. Patsy’s personality was undergoing a change – his moods became excessively brooding and violent. I was soon to find out what that entailed.

I had gone with George to the Nell Gwynne Café in Covent Garden. It was packed to capacity. You got very good food there, and George and I and a couple of porters sat at a table for four in an L-shaped section of the café. I was about to get stuck into my baby’s head and two veg (meat pudding – a speciality of the house) when Patsy walked in. I looked up and greeted him, ‘Hiya, Patsy.’ He didn’t reply. Instead, he smashed me full in the face with a left hook. I crashed backwards over the table behind me and rolled on to the floor. I was up on my feet like a shot and steamed straight into him with blood pouring from my nose. We’d been the best of pals, stood together, fought together, protected each other. We’d been like brothers. Now he was laying into me – and Patsy could have a fight.

All the customers cleared the area and became spectators. People outside hearing the commotion came in and stood on tables and chairs to get a better view. As we battled, everything around us got wrecked: mirrors, pictures on walls and chairs. We really went at it. I finished up getting him in a stranglehold on the floor. His face was in my stomach and he was kicking his legs like a man struggling to stay alive.

‘Fred, don’t choke him, he’s gonna be dead. You’re killing him,’ someone warned me.

But I wouldn’t let go and still had a cross-collar hold. My old judo was coming in handy and he was gasping away, going blue in the face. They pulled me off him – not a moment too soon. He was already semi-conscious and closer to death than I’d realised. By now the police had been called and just before they arrived we were hustled out to the pub next door. We used to drink in there and the governor let us use the toilets to clean up.

While we were washing, George and some of the porters came down and told us we were silly boys to fight like that when we’d been such good friends. I gestured at Patsy: ‘Talk to him about it.’

Any thoughts of a reconciliation were abandoned when, shortly afterwards, George picked up a leather cobbler’s knife with a curved blade and wooden handle. They were a common – and lethal – tool for cutting people in those days. Sharp as a razor. When I saw that, my blood boiled. The blade had been meant for me. I went to do Patsy there and then in the toilet, with his own knife. I turned to him: ‘You’d fucking use this on me?’

With that, he broke down and started to cry, saying he was sorry but thought I had dropped him out and that I didn’t look on him as a best friend any more. He was convinced I’d blown him out and replaced him with my brother George.

My anger gave way to pity. I felt really sorry for him. It became obvious to me he was mentally ill. Afterwards, though, I could never feel the same about him again. What can you do with people like this? He was paranoid. Psychotic. All that we’d been through together and the close friendship we’d had destroyed on that day. And, although he’d never used the knife on me, I knew the intention had been there. From then on, we went our separate ways.

Patsy was always getting into fights and rows. As he got older, he became bigger and heavier. He once had a row with a taxi driver taking him to a pub in Covent Garden after he’d been drinking in the West End. The cabbie stopped outside Bow Street police station, sounding his horn. When police came running out, Patsy knocked two of them out, but was then overpowered and dragged into the cells. He finished up with a 12-month sentence and was sent to Wandsworth.

Patsy was always being carted off to the nuthouse for one reason or another. One time it was for trying to strangle his wife, Margie (a lovely girl). Some years later, he came to my pub, the Prince of Wales, when he knew I’d had a bit of aggravation. ‘I’m with you, Fred,’ he said, brandishing a shooter, which he’d pulled from his pocket. ‘I want to sign on the Firm again.’

I told him to put his gun away. There was no way I’d have a loose cannon like him about me. It was all very sad. Patsy was a lovely guy but, as I say, he was a sick man who needed help and never got it. In 1983, Patsy died of lung cancer in St Thomas’s Hospital. I often think of him and feel sad.

When I was 18 going on 19, I was introduced to my future wife, Maureen Puttnam, on a blind date arranged by my friends Sammy Osterman and his girlfriend, Joanie Winters. Sammy worked in the print and he and future Great Train robber Tommy Wisbey were old mates. Tommy worked for his dad, who had a bottle factory in Cook’s Road, Camberwell. His girlfriend, Renee Hill, whom he later married, was related to Joanie who was also a good friend of Maureen’s.

The girls aroused Maureen’s interest in me. They said I was always spending money like water and treated my women well. I wasn’t such a bad-looking chap either. We got on fine together and she was an absolutely straight girl. No funny business at all. It was ages before we made love, and in my way I respected her for that.

At my age, I didn’t feel ready for marriage but all my pals had girlfriends and were getting married so you just seemed to follow suit. Maureen must have had marriage in mind. I let her down two or three times on dates and once she came around to my house demanding to know why I hadn’t shown up. She was a strong girl. Our courtship, like our marriage, was volatile. She was very possessive and jealous and I couldn’t look at another girl without upsetting her. We were always rowing, sometimes even in the street.

There was a reason though: she had a very unhappy childhood and needed a lot of security, love and affection. She lived with her aunt Lizzy, who had a heart of gold. Whenever Lizzy was out of the house, Maureen and I would have a kiss and cuddle in the front room. We did all our courting there and also in the back row of the Kennington Odeon cinema.

Inevitably, Maureen fell pregnant with my Gregory and we got married at a church in Walworth Road on a Monday, which was the most convenient day for market and street traders. The wedding party was an all-day affair held at Tommy Wisbey’s sister-in-law Janie Shaw’s place, a four-storey home on the Walworth Road. It was a good day out and everyone enjoyed it. Maureen was given away by her uncle Joe; her father had been killed falling off the back of a lorry crossing Waterloo Bridge. (He had worked the smudge – camera – in Trafalgar Square, taking pictures of tourists until given that fateful lift by a grocer friend.)

We set up home in Milton Road, a wide tree-lined street in a very desirable part of Herne Hill, south London. Maureen gave up her job as a presser once we got married, but she always pulled her weight. I used to joke that she believed manual labour was a Spanish wrestler, but she was never frightened of hard work. When I got nicked, she went straight back to work at Waterloo Station on the tea and buffet cars. The job was handed down to members of the families and it kept her going while I was in the nick. She was also very protective of me and never frightened to weigh in physically on my behalf.

In the past, I’ve had to do a bit of ducking from Maureen myself. When we had the Prince of Wales pub in Lant Street and a flat on the Brandon Estate, Kennington, she once threw flowerpots at me from the 14th floor after a row. Another time, I’d been out with George, Bertie Blake, Buster and Tommy Wisbey and got home late – having popped out for a quiet drink, we finished up in Brighton! Maureen steamed into me and I legged it back to my car – a brand-new Citroën DS 19, painted in racing green – dodging a hail of stones, bricks and small change from her handbag, which dented the car roof. From the 14th floor, these missiles were as dangerous and deadly as bullets, causing sparks to fly off the pavement, nearly penetrating the roof of my new car. (I hate to think what they’d have done to my skull.)

But I could be just as angry towards her. On one occasion I was several hours late for Sunday lunch. When I arrived home from drinking after hours with the chaps, the roast smelled wonderful, but Maureen had retired to her bedroom with the Sunday papers. ‘That smells lovely,’ I complimented her, and went to the dining room, expecting her to serve up the food. Maureen came into the kitchen and without a word to me, opened the oven, took out the roast and went straight out the back door to the yard while I sat expectantly with my knife and fork at the ready. Instead of a steaming hot roast being delivered on my plate, I heard the sound of a knife scraping the serving plate as she emptied the lunch into the dustbin. She then trotted back in, disdainfully looking past me, and went straight back to the bedroom and her newspapers.

I was incensed. I went to the yard, picked up the dustbin, carried it to the bedroom and emptied the contents over her as she sat fully clothed on the bed. I then walked out of the house and returned to my cronies and carried on drinking. When I returned home a couple of days later, we were sweet as pie to one another. Childish really, but that was typical of our early days together.

Even before we married, Maureen had witnessed gang fights involving me and our friends. It was all part of life in those days. The Harrises picked on Sammy Osteruran outside a pub in Camberwell New Road one Sunday morning. Sammy got a glass in his face as a result of this feud with the Harris family. A terrible fight followed – in fact, the feud went on for several years. Tommy ended up working with them after the feud and one of the brothers, with whom I had a straightener, even came to my wedding. Later in our careers, we’d drink together and help each other out if there were any problems. Many of my early rivals have over the years become solid friends and we still drink together sometimes.

On one occasion, there was a row between the Harris family and Tommy Shaw, a bookmaker, involving bets and street pitches. Tommy was a generous man with a charming personality and was very successful. If you were short of a tenner, he’d give it to you. Curiously enough, when bookmaking became legal in Britain, licences were only given to those people who could prove they were in the business. So, for some, the only acceptable proof entitling them to those much-sought-after licences was to prove they had broken the law and had convictions for betting!

One of my mates at around this time was Horace ‘Horry’ Dance. He was an old friend from Battersea and lived in a nice respectable street just off Clapham Common. His mother was one of those well-spoken ladies who would proudly show you a photograph of her Horry immaculately turned out in his cricket whites surrounded by the rest of the team. The bit she didn’t reveal was that the photograph was taken in Borstal.

Horry was a well-known face and married a beautiful girl called Barbara. But he was a right handful – always in trouble and getting nicked for assaults on police. He had a powerful BSA Thunderflash motorbike on which we rode to work. I would do a snatch on a night safe while he would wait down an alleyway or round a corner. We’d make sure the numberplates were covered up and we disguised ourselves with pilot helmets and goggles. (There weren’t any crash helmets in those days.) After the snatch, we’d roar off. There were rich pickings to be had. We robbed furniture stores such as Times Furnishings, where the day’s takings might be left in a drawer minded only by an office girl. The money piled up from people bringing in their monthly instalments for goods that they’d bought on the drip (hire purchase).

Later on, we nicked a Vincent Black Shadow motorbike (the fastest motorbike on the roads) and used that to snatch money off managers and cashiers as they went to put cash in night safes. Indirectly, I gave some of it back later when I bought a Times Furnishings bedroom suite – for cash.

There was nothing Horace wouldn’t do for you. He was once in hospital with peritonitis when he heard that I’d been nicked. He pulled out the tubes connected to his stomach, got out of bed immediately and went to the police station to bail me out at Catford Magistrates’ Court. That’s the sort of chap Horry was.

And there was nothing he wouldn’t steal. Wherever he went, he carried a screwdriver and nicked everything he could take home. He bought three houses and built a fourth one entirely from stolen materials. There was a violent streak in the family too, though. His wife Barbara, who helped him build the house, was involved in a hilarious brawl with Horry’s mum and dad. The argument began inside the house and spilled out into the garden of their lovely suburban street, with neighbours peeping through curtains at the commotion. The garden became a battlefield. Both sides picked up stones, bricks and gardening tools – anything they could lay their hands on. They used metal dustbin lids as shields to protect themselves against the missiles. You can imagine the din.

For all that, they were lovely people and good friends. I didn’t see Horry for years and then learned the sad news that he’d taken his own life with an overdose.

In the early days, Horry had introduced me to some heavier people who were into bigger paydays than we were getting. For me, it was like serving an apprenticeship. I was continually progressing up the scale with more experienced people to whom Horry had sung my praises.

One of Horry’s past acquaintances was ‘Mad’ Mo Jones. When Mo came out of Wandsworth Prison after serving five years for cutting up a copper’s face, he called on Horry’s mother. We reckoned there might be a problem, because he and Horry had a fight some time previously, and so we tooled up. Thankfully, the meeting was amiable. Mo was with another chap I knew, Lennie Morgan, so we all shook hands.

This was a relief, as Mo Jones was a fearsome man. He was built like a brick shithouse and had a nasty temper with it. Mo was always tooled up and had a terrible reputation in and out of the nick. Once, I was invited to work with him and Lennie and another chap called Bertie Blake. We did a few post offices, tie-ups and pay snatches. In those days there were still trams and trolleybuses and one evening Mad Mo actually did a raid on a tram! Believe me, this was a one-off in the annals of crime. We had been waiting for the cashier of the Super Palace Cinema at Clapham Junction to leave the building with the day’s takings. We missed him and someone pointed out that he was getting on a tram. Mad Mo jumped on the same tram and we followed. He walked down the gangway, looking from left to right for someone holding a cash bag. When he found him, he asked the chap if he was the cashier.

The geezer confirmed he was and Mo grabbed him out of his seat and said, ‘Give me the fucking money!’ The poor chap handed it over without hesitation. Mo had that effect on people.

Something was bound to give eventually, and it happened in an unexpected way. Mo raped Lennie’s girlfriend Rose, a good-looker with a voluptuous body. He went around to her place, threatened her with a knife to her throat and then raped her. She came screaming and crying to Lennie and told him what had happened. Bertie Blake and I were unaware of this when Lennie called us for a meeting at the Prince’s Head pub.

When I got to the pub, Mo Jones was already there. He bought me a drink and I sat down with him. Mo and I waited an hour for Lennie and Bert to arrive, while having several drinks together. Then, Bert put his head through the door of the pub and waved me outside. He said Lennie wanted to show Mo something on his own and that we would meet back here later. Bert took Mo to meet him as arranged. I didn’t think any more about it and waited for them to return. As far as the customers and publican were concerned, though, I was the only identifiable person with Mo that night.

Our fashion in those days was to wear gabardine raincoats with epaulettes. It was the Robert Mitchum look – given currency by the film Build My Gallows High. Your hair was slicked back with gel, meeting in a duck’s arse at the back of your nut – the DA haircut. The look was big and baggy and, worst of all, easily identifiable. And Lennie was wearing an identical gabardine raincoat to mine.

Bert returned to the pub and again beckoned me outside. Lennie Morgan was there, with his coat collar turned up. ‘What’s going on?’ I asked.

‘I’ve done Mo! I’ve killed him,’ Lennie replied. He opened his coat and I could see he was smothered in blood.

‘Fuck me!’ I said. ‘That’s naughty.’

Lennie kept talking: ‘He’s gone to my home while I was out and fucking raped my Rosie with a knife to her throat. She was in a right state. She’s still in bed and can’t talk.’

I commiserated with him: ‘The bastard deserved it,’ I said. ‘Rosie’s a lovely girl.’

Rosie had the voice of an opera singer and could sing songs from all the shows, specialising in Ivor Novello tunes. Lennie was one of the chaps and well respected. He was then about 30 and I was still in my teens. He asked me if I thought Horry’s mother would give us a change of clothes. At that time, Horry was away doing nine months in Wandsworth for GBH on a copper. (It seemed all of our friends or acquaintances were in and out of Wandsworth at the time.) I went around to see Mrs Dance and she was a good old girl about it. She had a big fire going in the grate and we burned all of Lennie’s clothes. Then she gave us a fresh set belonging to Horry. We then cleaned out all the ashes and left.

But, later, I began thinking about the implications. If Mo was dead, I would have been the last person to be seen with him. I’d been sitting with him in the pub for several hours having a drink and had then gone out with him, although I had come back afterwards. It would still not look good if people recognised me, though. I started to visualise reports about me: ‘Young man with slicked-back hair, Latin looks, wearing gabardine coat. Wanted for murder…’

Later, Lennie told us what he’d done. He’d taken Mo to Spencer Park, which is close to Wandsworth nick. It was pitch black and was bordered by a row of large fashionable houses. Apparently, Lennie pointed to a house. ‘That’s the one we’re going to screw,’ he said. Then he stepped behind Mo, pulled out an iron bar and smashed him over the head several times. Mo held up his hands for protection but Lennie kept bashing away. He left him in a crumpled heap with his head split open and bleeding profusely. Nobody could survive an onslaught like that. Or so Lennie thought.

For two days, there was no mention of Mo. We had been looking in the newspapers for a murder report and were understandably concerned, since we risked getting hung for a lady’s honour. Then we read a report that screams had been heard in the park and police had discovered a considerable amount of blood, indicating that someone had been seriously injured. But no body.

A bit later, Bert got a message from Mo’s sister to call around to her house in Garratt Lane, Wandsworth High Street, about a mile from Spencer Park. Bertie was shitting himself when he went to see her. He pretended to be shocked to find Mo lying in bed with towels around his head. Mo was not to be fooled. His piggy eyes were alert. He told Bert that he had been led into a trap.

Mo’s look said that he would kill him if he had the strength. Then he took the towel away from his head and Bert said the wound was like looking into an open mouth. They had to take Mo to hospital then, or he would have died. He had two or three brain operations and several hundred stitches in his nut and hands. All his fingers had been crushed and broken during the attack.

Amazingly, he had crawled away from the spot to his sister’s house, leaving a trail of blood. But he wouldn’t let her call the police. He said nothing. That was the way it was then and always will be in our world.

Years later, Lennie was doing nine months in Wandsworth when who should come into the metal shop but Mo Jones. They looked at each other and immediately ran around the shop searching for tools. They were ready to kill each other. But they missed their chance. A screw saw what was happening and rang the alarm bell. They weren’t given the chance for a return contest and both were dragged down the block.

About four months after Lennie’s attack on Mo, we were out with Bert, Lennie’s girl Rose and Sylvester, a stallholder, and a lovely old guy who was a street bookmaker called Jack the Pie. We started out on a pub crawl and ended up at The Surprise in Vauxhall Bridge Road. We were in high spirits. The pub was packed and Rosie was sweetly chirping away some Noël Coward tunes at a grand piano in the corner. We boys were near the door laughing and playing around with Jack Pie, riling him about all the money we had lost to him over the years.

He took it all in good fun. But then we took it a step further: we grabbed Jack, tied him to a chair with our scarves and sat him on the tramlines in the middle of the road. It was about 10pm and trams used to come up there at speed. Poor Jack suddenly got scared, but we were close by, ready to drag him away as a tram approached. ‘This is what you get for taking our money,’ we shouted to him. The tram driver was frantically trying to slow down, winding the brake handles at a furious speed and donging the warning bell with his foot. He was convinced he would run over Jack. We dashed out and scooped Jack away with only seconds to spare. It was all boys’ stuff. Highly spirited antics inspired by plenty of gin-and-tonic and Scotch on the rocks.

Excitement over, we went back into the pub to hear Rose finishing her number and giving it the big one (she always finished her songs on a high note) when a load of coppers arrived from Peel House, a section house for training police, which was only two streets away. A fight started and spilled out into the street. One copper had a stranglehold on Lennie from behind. I pulled him off and cracked him one on the chin. The copper staggered back on his heels, right across the pavement. His back hit the railings gate and he disappeared down the basement steps. Oops! Very nasty.

Now all hell broke loose and everyone headed in different directions. I had three coppers chasing me up Vauxhall Bridge Road, intent to kill. I was running out of puff at the foot of Vauxhall Bridge and just made it on to a departing tram. My legs were gone. I couldn’t step up off the platform. I looked around gasping for breath. The coppers were straddled in a long blue line a short distance away. One determined bastard, bent on getting his man, was closing up on me as the tram stood waiting to go.

The tram conductor came down the stairs, sized up the situation at a glance and without a moment’s hesitation gave the word for the tram to continue: ‘Dong dong, fares please.’ Magic words! He looked at me and winked.

‘Thanks, mate,’ I said, as I flopped down on the seat. The tram left the coppers labouring for breath and kicking the air in anger and frustration.

Unfortunately, Lennie, Bert, Jack and Sylvester were all arrested and received time for assault on the police. Lennie told me afterwards that, when they were arrested, they were taken down to the nick and all of them were pressed (a polite word for it) to reveal my name. But they all stood up – strong men, solid men – and wouldn’t tell the police anything. At the magistrates’ court, the coppers came to give evidence swathed head to toe in bandages. Lennie got nine months, the others three and four months.

As each of them was released, we had another piss-up and a good laugh. Lennie, like me, also had a brother called George, who had some good contacts in the car business. George was keen to get some muscle on his firm and wanted to include me in everything. He told me that he had a man in County Hall who could get brand-new car log books and stamps. Would I like to go into business with him? I jumped at the chance: ‘When do we start?’ I pulled my brother George in on the action and got myself a set of twelves (keys). They would open most of the cars we had targeted for nicking: Ford Prefects and Austin A40s. If the key didn’t fit, then two screwdrivers were all you needed to break in through the small quarter-light side window with very little damage done.

My job was to nick the cars, then drive them to Tunbridge Wells and park them up. My George would follow and take me back to London. A car dealer he knew in town would put them in his showroom furnished with a log book and all the right details. They started to go like hot cakes. George and I were doing very well. In fact, the lock-up garages were full and I was told not to nick any more for a while. But all good things come to an end.

The showroom sold a Ford to a man who was very knowledgeable and he spotted a number behind the sun visor that shouldn’t have been on that particular year and model. He called the police and the dealer was arrested. They traced the log books back to County Hall, but nobody grassed on our firm. The wartime propaganda – that golden rule that insisted on silence – still held good.

Georgie Morgan’s next scheme was counterfeiting and we had a load of white fivers printed up. But that one was short-lived. One of his relations, who did a bit of work for him, nicked a parcel of the dodgies and went to Wandsworth dog track, where he got himself nicked. Then, on top of that, George Morgan got nicked and it all blew up in our faces.

It was clearly time for me to move further up the ladder and try something new.