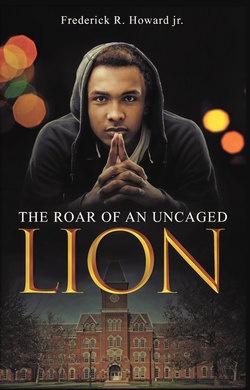

Читать книгу The Roar of an Uncaged Lion - Frederick Howard Jr. - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Manifestation of Corruption

ОглавлениеAs a young adult, all that I had unconsciously learned became me and I started to manifest the corruption without thinking. There’s a saying in the hood that says, “What is in you will come out, so there’s no need to try to be what you’re not.” In my case, that saying proved true. Everything about me at that time was corrupt, because there was no longer a battle being waged: I had fully embraced the corruption. I used the hate, the frustration, and the pain as a weapon that I unleashed upon the world. These emotions held no negative connotation for me, but were delicate maidens that I caressed as I danced to the song of the streets. There was no way to stop the dance, nor did I want the song to stop. I challenged everyone and everything, I respected no one, and there was nothing I wouldn’t do to further my position. Everything was on the table to be used or knocked off at my discretion. All that I had become was a direct result of my upbringing and my environment. As my environment changed so did the principles and rules that governed it, and to learn the new principles a teacher was needed.

Hen was our teacher, because he was what Jay-Jay and I wanted to be. Hen was a jokester but rubbed the wrong way he was vicious; he defended us like a male lion defends his pride. When he was with us, there was no foe we feared or couldn’t defeat. So my first two years on the streets wasn’t really on the streets. I spent most of the day in Pacifica at Hen’s and Jay-Jay’s house and at night I slept in their closet. At Hen’s and Jay-Jay’s house, school was always in session and lessons were always being taught. If Hen wasn’t teaching, then it was his mother or grandmother at the front of the class. I matured at their house, and soaked up the knowledge that helped me become the villain I listened to on rap tapes. Although my manifestation of corruption began at Hen and Jay-Jay’s house, mixed in with the corrupt lessons were good, sound, righteous morals. These principles were being taught by their mother and grandmother and, like the corruption, they stuck with me.

Hen’s mother was in my opinion the best mother I had ever seen. Her name was Alana. She was a 5’5”, dark- skinned slender woman of about thirty-three. Alana’s character was gentle, humble, and hardworking. She maintained the authority in the house but never raised her voice or struck anyone. If I had to describe her with one word, it would be dedicated. When I met their family, they lived in the Tenderloin. The family consisted of Alana, her daughter Anna, the boys, and their stepdad, Tony. These five members of their family shared a studio but through Alana’s hard work they moved to a two-bedroom. But a year after the move, Alana moved her family into a four-bedroom in the suburbs of San Francisco. She still wasn’t satisfied and in the next four years she obtained her own house. From Alana I learned that even though doing what’s right takes longer to benefit you, in the end hard work always pays off. But at my age I wasn’t into waiting, so I went for the quick fix—hustling. Being an aspiring criminal I had to be flexible: I could not always sell drugs, but I could always get a young lady to do my bidding.

For two years I preyed upon the women in the town we lived in, manifesting many of the corrupt morals that I unconsciously learned as a child. These principles taught me to prey upon the weak, never to trust anyone, and to use my powers to dominate and control with no compassion. I lied to, cheated on, and manipulated the young women I dated; for me it was like a game. My experience and environment told me that was the way to manhood. And being a child I didn’t question; I just followed and hoped that no one singled me out as being different. To hide my fears I had become a predator, seeking to benefit in every situation and from every relationship.

As a result, I was no longer welcomed at Hen and Jay-Jay’s house: their mom saw straight through me and knew I was up to no good. One day we came home and I heard Alana tell Jay-Jay, “Go get Fred and tell him he has a phone call.”

I ran, picked up the phone, and said, “Hello!” To my surprise, it was my grandmother.

She said, “Tootie, it’s time for you to come home. You have a family that loves and misses you.”

I looked up and Alana just walked away. To this day I don’t know how either one of those women could have gotten the other’s phone number, but either way I was on to new territory.

I ended up back in San Francisco, at my grandmother’s house in Hunters Point. Hunters Point at that time was sectioned off by the gangs. These gangs feuded back and forth with each other and made walking in the neighborhood dangerous. My grandparents sat me down and gave me the rules.

My grandfather said, “Tootie, be home before nine o’clock; this ain’t the suburbs and here kids are getting killed.”

I said, “Okay,” but in my mind I was thinking I can handle myself.

One bright spot about living with my grandparents was that I got to spend time with my cousin Nicole. Nicole was a pretty, light-skinned, chubby black young lady; she was my age but wasn’t into anything that would have interested me. She had graduated from high school, worked, and mostly stayed at home on her off days. Out of the house we lived in two different worlds, but in the house we were always on the same page. After I broke the curfew for the tenth time, my grandmother sent me to live with my auntie Sherryl. My auntie was a 5’4,” slender, brown-skinned pretty woman who spoke her mind and lived in the Oakdale Projects.

The Oakdale Projects was located in the back part of Hunters Point and was a mixture of townhouses and projects, but the kids were all hood. As I walked up to the door of my auntie’s house, I could see all the kids looking at me. Before I could knock, the door swung open and out jumped my three cousins. Demetri was a brown-skinned, curly-hair young black kid. He was the oldest and had a mind of his own which he never had a problem speaking. Then there was Conrad, a short dark-skinned young man of about twelve who was quiet but always watching and learning. The baby was little Bobby. He was light-skinned, with red freckles, and sandy red hair. These three had never played outside on Oakdale, but that was soon to change. My cousins were happy to see me for their own reasons, and I was glad to see them because of mine.

As we ran upstairs, little Bobby turned to me and asked, “Tootie, you want to play with me on my Super Nintendo?”

I responded, “Sure, why not.”

As we played upstairs, we heard a car crash. We ran to the window to see what had happened and expected to see only a fender-bender; we would have never guessed that we would see a real live shootout between two carloads of heavily armed young men. This was my first day on Oakdale and I loved it.