Читать книгу Frederick Douglass in Brooklyn - Frederick Douglass - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

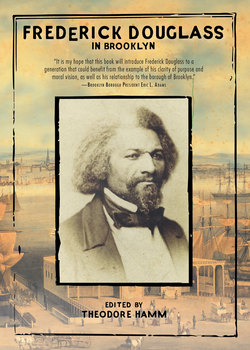

Mr. Douglass has been in the habit of carrying his audiences by storm. His peculiar wit, sarcasm, drollery, dramatic intensity, and, more than all, his noble moral earnestness, set in strong relief by an indefinable and touching sadness of tone and mien, [are] apparent [in] all his speeches. Though he makes his listeners alternately cheer, laugh, and weep, they inevitably carry away with them, as the chief impression of the evening, not the ornament or side-play, but the logical frame-work and solid sense of the discourse. Frederick Douglass, beginning his life as a bond-slave, will leave behind him an honest fame as one of the chief orators of his day and generation.

—Brooklyn’s Theodore Tilton, Independent,

February 12, 1863

Upon Frederick Douglass’s death in 1895, the New York Tribune—a newspaper founded by a leading abolitionist, Horace Greeley—dug up a chestnut from a half-century earlier. In 1846, Douglass had delivered a speech at a temperance gathering in London’s Covent Garden Theatre. There he told an audience that included both British royalty and US ministers that while temperance was indeed a worthy cause, the abolition of slavery was more important. After Douglass’s address, the Tribune said, among those who sought to congratulate the speaker was an “eminent Brooklyn divine.” Never one to mince words, Douglass rejected the overture. He told the minister, “Sir, were we to have met under similar circumstances in Brooklyn, you would never have ventured to take my hand, and you shall not do it here.”[1]

Beyond illustrating Douglass’s resolute character, the anecdote also yields insight into Brooklyn’s race relations in the decades before the Civil War. Despite the presence of prominent white abolitionists, as well as that of vocal African Americans, Brooklyn was far from a haven of black equality. In the wake of the London meeting, Douglass engaged in a high-profile war of words in print with Reverend Samuel Hanson Cox, the prominent pastor of Brooklyn’s First Presbyterian Church. Though an abolitionist, Cox was outraged that Douglass had raised the issue of slavery at the temperance convention. In the New York Evangelist, a Presbyterian weekly newspaper, Cox called Douglass’s actions a “perversion” of the meeting’s intent and “abominable!” In William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator, an influential abolitionist paper from Boston, Douglass labeled Cox a “sham” opponent of slavery. Audiences across the Northeast thus became aware of Brooklyn’s contested racial terrain.[2]

Frederick Douglass never lived in Brooklyn, but his visits to the “City of Churches” stirred both enthusiasm and controversy. During the Civil War era many of his key friends and allies—including Henry Ward Beecher, Theodore Tilton, Lewis Tappan, James and Elizabeth Gloucester, James McCune Smith, and William J. Wilson (a.k.a. “Ethiop”)—called Brooklyn home. Douglass had close ties to three publications with Brooklyn roots: the Ram’s Horn (1847–1849), the Anglo-African (1859–1865), and the Independent (1860s). Meanwhile, his own publications, the North Star and Frederick Douglass’ Paper, featured regular Brooklyn correspondents, most notably Ethiop. Douglass was a close friend of John Brown, and the pages of the Anglo-African noted the former’s stop in Brooklyn—at the home of Elizabeth Gloucester—en route to a pivotal Harpers Ferry planning meeting in late August 1859. Theodore Tilton, who rose to prominence in his defense of Brown in the Independent, would become one of Douglass’s closest confidants during the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Both in person and print, Douglass was a powerful presence in Brooklyn—and the varied reactions to his positions on abolition and black equality thus illustrate the ways in which those issues shaped the city in its formative decades. At African American churches like Reverend James N. Gloucester’s Siloam Presbyterian or James Morris Williams’s Bridge Street AME, or at white abolitionist strongholds like Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Church, the gifted orator received a hero’s welcome. But in the pages of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, a conservative Democratic organ during the Civil War, Douglass was often subjected to racist ridicule. Douglass had garnered a more friendly reception from Walt Whitman, during the latter’s short stints as editor of both the Eagle and the Brooklyn Daily Times. Even so, Whitman’s position on racial issues—antislavery but not proequality—reflected a notable current of local sentiment. Like New York City, Brooklyn (its own city until 1898) had strong economic ties to Southern slavery, making the place a racial minefield. But with the help of his steadfast allies, Douglass navigated it safely.

* * *

Twenty-year-old Frederick Bailey first became acquainted with New York abolitionists in September 1838. Born a slave on the Eastern Shore of Maryland around February 1818, Bailey came of age in Baltimore, where he learned to read and soon inspired his peers to do the same; after a few unsuccessful attempts to escape, he fled safely to New York via trains and ferries while carrying the identification papers of a free black seaman. Once in Manhattan, Bailey sought out David Ruggles, a leading African American conductor of the Underground Railroad. He informed Ruggles of his desire to marry his fiancée, Anna Murray, who would soon join him in New York; soon thereafter, Reverend James W.C. Pennington came from Brooklyn to perform the wedding at Ruggles’s home on Lispenard Street. (Thus began a long alliance between the soon-to-be Douglass and Pennington—who would preside over Shiloh Presbyterian, an abolitionist stronghold on Prince Street in Manhattan.) From New York, Frederick and Anna traveled via boat to Newport, Rhode Island, then by stagecoach to New Bedford, Massachusetts, where they set up shop and became the Douglass family. In the summer of 1841, Douglass first met William Lloyd Garrison, who helped launch his career as a public figure. That fall, the family moved to Lynn, Massachusetts, and it was there that Douglass wrote the book that would build his international reputation, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, which Garrison’s American Anti-Slavery Society published in 1845.

Brooklyn was far from a bastion of abolitionist support in the mid-1840s. Many early Kings County residents had owned slaves, and after Brooklyn officially became a city in 1834, local merchants competed with their counterparts across the East River for the trade in Southern products. Indeed, so widespread was the support for slavery in Brooklyn that in 1839 David Ruggles called the city “the Savannah of New York.”[3] Beginning in May 1842, Douglass spoke at the annual meetings of the Garrison-led American Anti-Slavery Society in Manhattan, which usually took place at the Broadway Tabernacle, the church where the Tappan brothers held sway. Beyond abolitionist circles, Douglass was not a household name in the New York area until his autobiography came out—and even then Brooklyn audiences more likely read about him in Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune (which published a front-page review by Margaret Fuller in June 1845) than in any local publication. Douglass, in turn, spent the next two years touring Ireland and England. Among his fellow speakers at the August 1846 temperance convention in London was Henry Ward Beecher, the charismatic Congregationalist minister who moved the following year from Indiana to Brooklyn, where he became the first pastor of Plymouth Church. Beecher’s arrival meant that Douglass and his fellow abolitionists in Brooklyn now had a much more sympathetic ally than Samuel Cox.

* * *

Upon his return from England in the spring of 1847, Douglass informed his colleagues that he planned to start his own publication. He was still based in Lynn, but sought independence from Garrison, who presided over Boston-area abolitionists. Throughout 1847, various reports placed Douglass’s publication in different locations, including Lynn, Cleveland, and Rochester, its eventual home. One of the earliest announcements came from Walt Whitman, who had been editing the Brooklyn Daily Eagle for just over a year. In early June of 1847, Whitman noted:

Fred. Douglass, the runaway slave, having received the necessary subscriptions and contributions for a press etc., from Scotland principally, is about to publish an anti-slavery paper in Lynn, Mass. He will of course create a great sensation in the regions around shoe-dom. A Sunday paper says that Lynn and the neighboring peninsula of Nahant have heretofore mainly depended for excitement on the appearance of the sea serpent, whose visits of late years have been singularly irregular. Douglass will prove a first-rate substitute for the monster.[4]

Playful but clearly supportive, Whitman’s statement was based on word that spread in the wake of the May annual meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society at the Broadway Tabernacle, where Douglass had spoken. There is no record of the two figures formally meeting one another, but at the time Whitman and Douglass were traveling in similar circles—and the former’s opposition to slavery would cause him to lose his job at the Eagle in early 1848.

As he prepared to launch his own paper, Douglass also became involved with the Ram’s Horn, which was published by Willis Hodges, a leading figure in the black community in Williamsburgh (as it was spelled at the time), which would not become part of Brooklyn until 1855. The Ram’s Horn debuted in January 1847, with Thomas Van Rensselaer, a former slave turned Manhattan restaurateur, as its editor. Hodges, who became close friends with John Brown, had owned a small grocery stand near the ferry in Williamsburgh, and his brother William was also a leading minister in the area. After the May meeting of the Anti-Slavery Society, Douglass wrote to van Rensselaer, encouraging him to “Blow away on your ‘Ram’s Horn’! Its wild, rough, uncultivated notes may grate harshly on the ear of [the] refined . . . but sure I am that its voice will be pleasurable to the slave, and terrible to the slaveholder.”[5] In early August 1847, the paper announced that Douglass had joined the masthead as an assistant editor; Sydney Howard Gay, editor of the National Anti-Slavery Standard (also based in Manhattan), confirmed that report, adding that Douglass would also serve as a regular contributor to the Standard. Douglass, in turn, asked Gay to look into the Horn’s finances, in order to make sure he wouldn’t incur any debts.[6] For the next several months, Douglass remained affiliated with the Ram’s Horn.

In the fall of 1847, African American audiences on both sides of the East River could thus read a weekly paper that featured Frederick Douglass on its masthead. The banner across page one of the only extant copy of the Ram’s Horn—dated November 5, 1847—lists Van Rensselaer and Douglass as editors, placing their names on opposite sides of the paper’s motto: We are Men—and therefore interested in whatever concerns Men. It’s not clear what Douglass actually contributed to this (or any other) issue, but the editorial page carried his name in the top left-hand corner. Under it was a signed editorial from Willis Hodges encouraging readers to take interest in the “Gerrit Smith Lands.” Smith was a prominent abolitionist from Western New York who encouraged blacks (and white abolitionists) to become farmers on the 120,000 acres he donated to a community called “Timbuctoo” in North Elba, near Lake Placid. In the fall of 1848, Hodges became one of several New York City–area migrants to Timbuctoo, where fellow resident John Brown (a Ram’s Horn contributor) helped him set up shop.[7] Gerrit Smith, meanwhile, would become a pivotal supporter of both Douglass’s own paper as well as Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry. In 1849, Van Rensselaer moved the Ram’s Horn to Philadelphia, where it fizzled out a year later.

That same November 1847 issue of the Ram’s Horn also carried an announcement informing readers that contrary to recent reports, Douglass planned to publish his own paper in Rochester, not Cleveland.[8] One month later, the North Star indeed made its debut from the city on the banks of Lake Ontario that Douglass would call home for the next twenty-three years. In his inaugural statement, Douglass declared, “It has long been our anxious wish to see . . . [a paper] under the complete control and direction of the immediate victims of slavery and oppression.”[9] That jab seemed directed at Garrison and the Liberator, because it didn’t apply to the Ram’s Horn (or other preceding black-edited newspapers). But in order to sustain the North Star, Douglass needed to raise a steady stream of funds, via both donations and subscriptions. While Gerrit Smith was a steady source of financial support, according to biographer William McFeely, over the next few years, “Everywhere he went, Douglass urged his listeners to subscribe.”[10] Such efforts brought him down to New York City and eventually to Brooklyn.

* * *

On April 16, 1849, Douglass made his first public appearance in Brooklyn, at Reverend James N. Gloucester’s Siloam Presbyterian Church on Myrtle Avenue at the edge of what is now Downtown Brooklyn. According to the Ram’s Horn’s report (which Douglass reprinted in his paper), the speaker had a dual purpose: “to lecture us on the subject of improvement, and [to] procure subscribers for the North Star.” In his own account, Douglass observed that Siloam’s location at that time was a “beautiful and commodious church under the pastoral care of Mr. Gloucester”; he also noted that after his talk, Van Rensselaer (with whom he stayed) made a “warm and vigorous appeal for the North Star.”[11] Both reports commended Reverend Gloucester and his Manhattan counterpart, Reverend Pennington, for allowing Douglass to use their churches without charging admission, which stood in contrast to Zion AME in lower Manhattan. Like Pennington, Gloucester remained a prominent figure in New York abolitionism. In February 1858, he and his wife Elizabeth, a savvy businesswoman who helped finance the construction of Siloam’s first full church, would host John Brown for a week at their home in Downtown Brooklyn.[12]

The black community’s attempts to build its future in the fast-growing city would be chronicled first in the pages of the North Star, where Douglass regularly printed letters from correspondents based elsewhere. Joseph C. Holly, a shoemaker by trade, was the paper’s man in Brooklyn. In a May 1849 dispatch, Holly reported about an abolitionist gathering at which the mention of Douglass’s name brought forth a “most rapturous applause.”[13] That July, Father Theobald Mathew, a leading temperance advocate from Ireland, made a high-profile visit to Brooklyn. As Holly noted in the North Star, Mathew, who had met with Douglass in Cork a few years earlier, now “took him by the hand in Brooklyn”—a notable gesture of solidarity in an increasingly hostile racial climate.[14] In 1851, the annual May meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society had to be moved out of Manhattan because of increasing antiabolitionist violence, and organizers quickly found that they were not welcome in Brooklyn, either. (The gathering took place in Syracuse.) That summer, the North Star became Frederick Douglass’ Paper, which brought the editor closer to Gerrit Smith (who bankrolled the publication), a move that caused a hostile split between Douglass and Garrison.[15]

In the pages of Frederick Douglass’ Paper, Brooklyn correspondents assumed a more prominent role. In April 1852, James N. Still, a self-employed tailor who used the pen name “Observer,” highlighted the success of a recent series of talks in Brooklyn by Reverend Pennington as well as Beecher’s growing prominence in local abolitionist circles. In Still’s view, such efforts suggested that the “time will come” soon when Douglass would join that network of speakers in the area. Though Brooklyn was announced on his tour itinerary in early 1855, the event never happened, and Douglass’s first widely publicized lecture would not take place in the city until 1859.[16] Yet as recorded by his paper’s most prolific Brooklyn correspondent, William “Ethiop” Wilson, Douglass made well-received visits to Brooklyn in the middle of the decade. Included in the more than fifty letters that the editor would publish from Ethiop, a school principal in Weeksville, was mention of Douglass’s February 1855 visit to Plymouth Church. He attended with Lewis Tappan, now a member of Beecher’s congregation, and the two sat together in Tappan’s centrally located pew. According to Ethiop, Douglass was “the observed of all observers, and the lion of the occasion,” disrupting the “pious devotions” of the church service. Beecher’s name had shown up frequently, and favorably, in Douglass’s publications for the preceding seven years, and the editor also mentioned that he had visited Plymouth at least one other time, in May 1854.[17]

Throughout the 1850s, Beecher ascended to prominence as an abolitionist, and the theatrical performer became a fixture on the national lecture circuit. At the same time, the Independent also enabled him to reach audiences beyond those who came to Plymouth Church. Launched in late 1848 as both a Congregationalist and abolitionist publication, the weekly paper’s driving force in the next decade was publisher Henry C. Bowen, a Brooklyn resident, Lewis Tappan’s son-in-law, and a successful merchant who had helped found Plymouth Church. Yet as Beecher’s fame grew, the Independent came to be seen as his vehicle. In 1857, Bowen, realizing that the freewheeling minister needed some help managing the publication, hired a brash twenty-two-year-old New York City journalist named Theodore Tilton.[18] Toward the decade’s end, Tilton established his national reputation as an abolitionist when the Independent published his widely reprinted interview with Mary Brown on the eve of her husband John’s execution. (On her way to and from Harpers Ferry, Mary stayed at Tilton’s home in Brooklyn.) As the Civil War began, the Independent was a leading national voice of abolition, with regular contributions from Horace Greeley, poet John Greenleaf Whittier, and its figurehead’s sister, Harriet Beecher Stowe. At the behest of Tilton, who steered the ship in the 1860s, Douglass soon joined those ranks.

In the several years prior to his January 1859 lecture in Williamsburgh, Douglass did not make any noteworthy public appearances in Brooklyn. But during that time he served as a lightning rod for the virulently proslavery Brooklyn Eagle. In August 1856, the paper warned of “Fred Douglass, the Negro co-laborer of the white-skin[n]ed niggers of Abolition . . . The doctrines of this fellow are that slaves should not only run away but murder their employers before starting.” In 1857, the Supreme Court sanctioned such hostilities, issuing its landmark Dred Scott decision declaring that slaves were property rather than people. When Dred Scott, the person in question, died in September 1858, the Eagle compared him to leading black public figures. Most absurdly, the paper declared that “Fred Douglass, the smartest darkey we have produced, will leave no name beyond his generation, but Dred Scott, a poor simple-minded old Negro . . . will live in the annals of this great nation, as connected with a great constitutional principle.”[19] Such blatant racism in the daily local papers no doubt fueled the resolve of John Brown’s supporters, and during 1858 and 1859, the Gloucesters actively participated in planning for the Harpers Ferry raid. Douglass, in turn, worked closely with the Brooklyn couple in aiding Brown. In February 1858, Brown left Douglass’s home in Rochester and one of his next stops was the Gloucesters’ place at 265 Bridge Street (now MetroTech) for the aforementioned weeklong stay. As noted by the pioneering black historian , there Brown informed his Brooklyn hosts that any money sent on his behalf should be directed to Douglass in Rochester. In welcoming Brown to their home, James Gloucester told him, “I wish you Godspeed in your glorious work.”[20]

Douglass, the Gloucesters, and an array of familiar New York City–area names would soon appear regularly in the pages of the Weekly Anglo-African, a publication that debuted in July 1859 (as an offshoot of an eponymous magazine). The publishers were two African American brothers from Brooklyn, Thomas and Robert Hamilton,[21] while its eventual leading editor was Douglass’s friend James McCune Smith,[22] who moved to Williamsburgh after the Draft Riots of 1863. Along with Douglass and Smith, the Anglo-African’s roster of regular contributors included New York City ministers Pennington and Henry Highland Garnet, Douglass’s longtime editorial companions Martin Delany and William C. Nell, and Brooklyn mainstays Reverend Gloucester, William J. Wilson, and Junius C. Morel. Despite such an all-star cast (and modest financial backing from Gerrit Smith), the paper struggled financially, and two years after its founding, the Hamiltons temporarily ceded control to James Redpath, a leading white proponent of Haiti colonization schemes for freed slaves (which Douglass briefly supported). In the summer of 1861, James McCune Smith, an opponent of colonization, led a successful effort to restore the Hamiltons’ control of the publication.[23] Over the ensuing several issues, a fundraising letter from James Gloucester appeared atop the Anglo-African’s editorial page. That November, the paper began serializing Martin Delany’s novel Blake; or the Huts of America—and early the next year, the author, a leading early voice of pan-Africanism, listed his address as 97 High Street, at the edge of Brooklyn Heights.[24] Like the Independent, the Anglo-African’s office was in Manhattan (near Park Row), but it was closely identified with Brooklyn.

The Anglo-African also provided extensive coverage of the assault on Harpers Ferry, including important details regarding Douglass’s role in supporting John Brown, a matter of historical dispute.[25] In mid-August 1859, Douglass stayed overnight at the Gloucesters’ home on his way to meet Brown in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania; while in town, the Anglo-African noted at the time, Douglass stopped by their office for “a short visit.” A few weeks later, the paper reported that “Frederick Douglass, Esq., will leave this city [New York] in early November, on a lecturing tour through Great Britain.”[26] It was a seemingly uncontroversial announcement, but Douglass would later use his stated travel plans as evidence that he was not planning to join Brown in Virginia, a charge leveled against him at the time. Like the leading daily papers in New York and Brooklyn, the Anglo-African documented the mid-October attack and its aftermath in exhaustive detail. Meanwhile, proslavery forces—led by the New York Herald—eagerly sought to implicate Douglass, who at the end of October fired back at his accusers in a letter to the Rochester Democrat. Though he did not denounce Brown and company, Douglass denied that he had “encouraged” their actions. He further insisted that he would never make any “promise so rash and wild” as a vow to participate.[27]

Over the course of three issues in late October and early November, the Anglo-African published a lengthy chronicle of Brown’s weeklong trial. Compiled from various newspaper accounts, the series’ final installment closed with a sampling of the material found in Brown’s carpetbag after his capture. Of the 102 letters in Brown’s possession, the paper printed two. The first read:

Brooklyn August 18 ’59

Esteemed Friend

I gladly avail myself of the opportunity offered by our friend Mr. F. Douglass, who has just called upon us previous to his visit to you, to enclose to you for the good cause in which you are such a zealous laborer. A small amount [ten dollars] which please accept with my most ardent wishes for its, and your, benefit.

The visit of our mutual Friend Douglass has somewhat revived my rather drooping spirits in the cause, but seeing such ambition & enterprise in him I am again encouraged. [W]ith best wishes for your welfare and prosperity & the good of your Cause. I subscribe myself Your sincere friend

MRS. E.A. GLOUCESTER

Please write to me with best respects to your son.

In the second letter, James H. Harris, a black friend of Brown’s in Cleveland, mentioned the trouble he was having raising funds there, complaining of the lack of resolve of the “whole Negro set.”[28] While the Anglo-African’s selections seem intended to illustrate the sturdy support for Brown received from his closest black allies in Brooklyn—the Gloucesters—Elizabeth’s communique also clearly identified Douglass’s role as a conduit of material support. The latter’s own dispatch to the Rochester Democrat, in which he denied any role in Brown’s actions, followed the letters from Gloucester and Harris. Although the excerpts ran without introductory comment, the many members of Douglass’s inner circle who read the Anglo-African no doubt knew the score: Douglass was clearly implicated in Brown’s assault on slavery.

* * *

In the aftermath of the Civil War, John Brown would serve as one key touchstone for Douglass, and Abraham Lincoln would be another. Douglass did not meet Lincoln until August 1863, but the two had common friends and associates. In late February 1860, Lincoln came to see Beecher in action at Plymouth Church, the initial planned location for the landmark antislavery speech he ended up delivering the next day at Cooper Union; the Independent’s Bowen and Tilton served as coorganizers of the Great Hall event.[29] When Douglass began to make high-profile appearances in Brooklyn in February 1863, Lincoln became a central figure in his lectures. Though Douglass came to like the president personally, he was often frustrated with Lincoln’s cautious handling of the war. But as historian Eric Foner observes, in the aftermath of the president’s assassination, Douglass began to elevate the fallen leader’s heroism, praising Lincoln in order “to get people’s support for Reconstruction.”[30] Such calculations were evident in many of Douglass’s Brooklyn appearances, most poignantly during his rousing January 1866 speech at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM), when he sang Lincoln’s praises and relentlessly trashed Andrew Johnson.

At that same BAM event, Douglass denounced the upsurge in anti–black equality sentiment stirring in Brooklyn, which the speaker had encountered first-hand during the run-up to the lecture. As he became close allies with Tilton, Douglass now experienced some ups and downs with Beecher—and after those two figures had their famous blowup in the 1870s, Douglass remained in Tilton’s camp.[31] In the speeches Douglass gave in Brooklyn during the Civil War and Reconstruction, the stars of John Brown and Abe Lincoln shone brightly. It was fitting, then, that the last two major addresses Douglass delivered in Brooklyn focused on the lives of these two pivotal figures.

Whether at BAM, Plymouth Church, or Bridge Street AME, at an Emancipation Jubilee in Bedford-Stuyvesant or the Union League in Crown Heights, Douglass struck up lively conversations with his audiences. During the Civil War and into Reconstruction, he also continued to incur heavy fire from the Brooklyn Eagle. In the following selections of his speeches and responses to them,[32] we see Douglass’s brilliance on display, and in the process learn a bit about the Brooklyn he knew well.

Editor’s Note

In editing the speeches, my goal was to present as accurately as possible what Douglass stated at each of the Brooklyn events. Some of the lectures here (Chapters 1, 3, and 8) combine Douglass’s published versions with accounts from newspapers. Others rely primarily on newspaper transcriptions of the speeches (Chapters 2, 4–7, and 9). At the end of the brief introductions to each chapter, I identify the main sources.

So as not to distract readers by noting every typo or unclear pronoun found in the newspaper coverage, I simply fixed some of them. Similarly, in certain portions of the speeches, I adhered to contemporary rules for capitalization (especially regarding proper nouns) and modernized some punctuation (particularly in the use of dashes). Rather than insert repeated or unclear ellipses, I chose to summarize in parentheses (or footnotes) the gist of any substantial deletions. For ease of readability, I inserted occasional paragraph returns. In general, most of the inconsistencies—in spelling, punctuation, and grammar—from the original texts of both the speeches and the newspaper reports have nonetheless been retained. The small changes noted above were made solely for the sake of clarity to the reader.

—T.H.