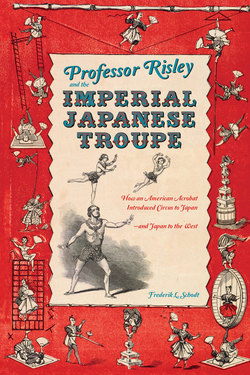

Читать книгу Professor Risley and the Imperial Japanese Troupe - Frederik L. Schodt - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

PREFACE

ОглавлениеOn my desk I have a reproduction of an 1887 children’s pop-up book by Lothar Meggendorfer called International Circus. It’s one of my prized possessions, for it shows not only how cosmopolitan the circus world was in the nineteenth century, but also how popular Japanese acts were. It’s a masterpiece of six scenes that unfold in three-dimensions and spectacular color, revealing Europeans, Africans, and Asians in a variety of acts. A Mr. Funtolo performs stunts atop his horse while it jumps over a flaming gate. Clara Springel leaps and somersaults through a hoop from atop her pony. And a man dressed in a Turkish outfit performs the “Sultan’s Courier,” straddling and standing on the backs of a quartet of galloping horses.

The fifth scene, the only nonequestrian one, is the most exotic. With the caption of “The clever acrobats of the Oriental Company perform amazing tricks,” it unfolds to show two pairs of kimono-clad Japanese acrobats, executing exciting feats of balance in front of an adoring European crowd of top-hatted men and bonnet-wearing women. One pair is doing a “perch” act. A man stands, balancing a soaring bamboo pole vertically from his hips, while a boy, skillfully holding on to the top of the pole, carries out a variety of gymnastic gyrations. Despite the herculean effort required, the man holding the pole is shown nonchalantly fanning himself with a Japanese folding fan. The other pair is performing the “transformation fox scene.” In this stunt, an adult Japanese man lies on his back on a mat on the ground, the top of his tonsured head facing us. His arms are free and he, too, is using one of his hands to fan himself, seemingly without a care in the world, but his legs are pointed straight up at the ceiling. On the soles of his feet he vertically balances a giant shoji screen, on top of which is poised a boy dressed up like a fox. This mischievous fox-boy has smashed many of the rice-paper panels of the screen while cavorting in and out of the frame, and he is making funny gestures at the amazed audience.

Both of these acts were regularly performed by Japanese acrobatic groups that toured the United States and Europe in the latter part of the nineteenth century. And no Japanese acrobatic group drew more attention than “Professor” Risley’s Imperial Japanese Troupe, for it was one of the first, arguably the best, and certainly the most influential. Indeed, the fox character in Meggendorfer’s pop-up book could well be a depiction of Hamaikari Umekichi, a young troupe member affectionately known as “Little All Right,” who in 1867 became a global celebrity, his name a metaphor for agility and panache.

“The clever acrobats of the Oriental Company perform amazing tricks.” Scene from Lothar Meggendorfer’s famous children’s pop-up book, International Circus, first published in 1877. meggendorfer, lothar. international circus: a reproduction of the antique pop-up book. london and new york: kestrel books; viking press, 1979.

*

I have spent much of my adult life writing about Japanese popular culture, technology, and history, and about the flow of information and people between Japan and the rest of the world. My circus connections are tenuous. As a boy I never seriously considered running away to join the Big Top, nor did I have any particular acrobatic talent. But I grew up on four different continents, and since my mother always liked the circus, we often went to see local shows and magic or juggling acts. For the last fifteen years or so, moreover, I have lived and worked only a few steps away from San Francisco’s Circus Center and with fascination watched aspiring young acrobats and jugglers and clowns train in its facilities. That, in addition to my interest in nineteenth-century cross-cultural events, is probably a big reason my curiosity was stimulated a few years back when I came across mentions in Japan of Professor Risley and his Imperial Japanese Troupe.

For me, this discovery of Risley and his troupe was quite an eye-opener. There are other well-documented examples of Japanese popular culture greatly influencing the outside world. The late nineteenth-century Japonisme art movement—when Japan’s “low culture” woodblock prints became the rage among “high culture” European and American artists—is one. The end-of-the-millennium “Cool Japan” movement—which includes modern Japanese manga, anime, fashion, and J-pop music and continues today—is another. Yet despite having studied and written about Japanese culture for decades, I had somehow been unaware of the late-nineteenth-century, short-lived global boom in the popularity of Japanese performers, especially acrobats. This other boom began right after the opening of Japan, after it had been secluded from the outside world for nearly two and a half centuries. It coexisted in time with the Japonisme art movement, yet had little in common with that movement except for its “Japanese-ness.” It involved not things, but people—Japanese commoners who were traveling overseas and viewing the West for the first time, and ordinary Europeans and Americans who were ogling the exotic performers from the East. And it was triggered by the work of Professor Risley.

It was inevitable, perhaps, that Risley and the Imperial Japanese Troupe, and even the global boom in Japanese performers that he helped spawn, would later be largely forgotten. Risley was literate. He straddled the worlds of both theatre and circus, and he could socialize with both the high and the low. But as far as is known, he never authored a book or diary or left any letters in his own hand that survive. There are numerous illustrations of him. Yet despite living a life that depended on self-promotion and publicity and extended well into the age of daguerreotypes, tintypes, and even modern photographs, the few photographs usually attributed to him—that might make him seem more modern—are difficult to authenticate. And despite his notoriety, he failed to inspire any writers of his era to write at length about him. The reasons for this include timing, his absence from the United States at critical periods, and the ultimate failure of many of his enterprises.

Another factor, however, is that, in both Japan and the West, circus and theatre performers existed on the fringes of normal society. Acrobats and jugglers, especially, were often only semiliterate and sometimes treated almost as social outcasts who inhabited a transient, ephemeral, and mysterious world. When generations turned over, when the twentieth century began, with all its revolutions and convulsions and new technology and slaughter, and when Japan forgot its own past in its pell-mell rush to modernize, many wonderful performers from earlier years faded from sight.

In doing the research for this book, the story of Professor Risley became as interesting to me as that of his Imperial Japanese Troupe. Risley was born in New Jersey around 1814 and died in a lunatic asylum in 1874. In an era of many larger-than-life figures, he was without doubt one of its more colorful characters. An acrobat who became an impresario, he was certainly one of the most widely traveled, for he went back and forth among multiple continents at a time when the average person was probably born, lived, and died within a fifty-mile radius. As an individual in the mid-nineteenth century who lived in the demimonde of the theatre and circus and left few records of his own, Risley’s movements are remarkably well-documented. Yet he remains a mysterious figure who fades in and out of the mist of history, sometimes coming into clear focus and then sometimes vanishing completely from view. While doing research on him, I constantly found myself consumed by burning questions. How did he decide to go to Japan? In 1866, how did he come up with the idea of forming a troupe of Japanese acrobats and jugglers and taking them overseas? How did he succeed, when so many others did not? What, in his background, made him such a pioneer in the globalization of popular culture?

This book will not answer every question about Risley and his Troupe, but I hope it will contribute to a greater awareness of them and will stimulate curiosity about the spread of popular culture and the performing arts around the world. If I can shed light on a little-known but fascinating story, and show how individuals—who may not have high social status or official connections—can transcend vast cultural differences and do extraordinary things, I will be happy.

*

Wherever possible I have relied on primary source information, rather than what others have written, and kept speculation to a minimum. Even thirty years ago, a project like this would have been next to impossible, because there was either not enough information available or it was too fragmented and difficult to access. Since then, however, several big changes have occurred.

In 1975, the diary of Takano Hirohachi—the overseer or manager of the Imperial Japanese Troupe—was rediscovered by some of his descendants in Iinomachi, his village in Japan. In the poorly documented world of semi-literate nineteenth-century popular entertainers, this diary is an extraordinary document. It is first and foremost a day-to-day, detailed record of the troupe’s movements in the United States and Europe, showing where they went and what they did. But it also represents the written impression of one of the first Japanese commoners—other than a few poor shipwrecked castaways—to see the West, after Japan’s nearly two hundred and fifty years of official seclusion from the outside world.

The discovery of the diary subsequently set in place a movement among Japanese writers and scholars to confirm the movements of the troupe, and to correlate them with global events. And without their formidable efforts my book would have been impossible. The original diary, in hard-to-read and fading, free flowing mid-nineteenth-century Japanese calligraphy—rendered by a social outsider who spoke a northeastern dialect and probably taught himself how to read and write—is exceedingly difficult to read today.

Luckily, in 1977 the Iinomachi historical society painstakingly transcribed Hirohachi’s handwritten diary and published it as a small, limited-edition book. This generated much media interest. In 1983 the well-known writer Yasuoka Shōtarō began serializing a story titled Daiseikimatsu saakasu (“The grand fin-de-siècle circus”) in the prestigious Asahi Journal magazine, and five years later it was compiled into what became a popular book. It was one of the first attempts to put the diary into a historical context, and it greatly helped raise awareness of Hirohachi’s story. In 1999, another book based on the diary appeared, titled Umi wo watatta bakumatsu no kyokugeidan (“The bakumatsu acrobatic troupe that crossed the seas”), by popular historian Miyanaga Takashi. In this case, Miyanaga undertook the physically daunting task of traveling to most of the sites mentioned in the diary and attempting to confirm them. During this period there was also considerable research done by other scholars, writing articles in journals and magazines. Of the academic researchers in Japan, no one has done as much work on the story of the Imperials as Mihara Aya, a specialist in nineteenth-century Japanese performing arts history, especially that of the multiple Japanese troupes that then toured the United States and Europe. Working with the local historians of Iinomachi, she painstakingly went back over the original diary, checked for errors, correlated it with her knowledge of the nineteenth-century entertainment world, and added new annotations. In 2005 her work was included in a multi-volume history of the Iinomachi area, and it is this transcription of the diary that has been most useful for me. Mihara’s other work on early Japanese troupes—in academic papers and articles and especially in a 2009 book that summarizes much of her research, titled Nihonjin tōjō: Seiyo gekijō de enjirareta Edo no misemono (“Enter Japanese: A Night in Japan at the Opera House”)—has also proved invaluable in unlocking many of the secrets of the Imperials and of Risley’s association with them.

The second thing that has made this book possible is new technology. The story of Risley and the Imperial Japanese Troupe is particularly complicated. It encompasses many languages and geographic regions, and it requires correlating a vast number of disparate shards of information. The travel expenses and the time required for a project like this would normally have been prohibitive. Research would have involved traveling to four continents, spending weeks if not months in libraries around the world, and poring over dusty original documents and viewing scratchy, blurred microfilm and fiche. I still spent considerable time in libraries in America, Europe, Asia, and Australia, but I was greatly aided by the development of online databases of scanned nineteenth-century newspapers and magazines that have recently become available to researchers. Each country has begun to implement these historical databases in different ways. Japan, alas, lags far behind the rest of the advanced world. The American databases are disparate, diverse, specialized, sometimes hard to use, and largely commercial. The French system is beautiful and broad and free and sometimes quirky. In an attempt to preserve their national heritage, many smaller countries now also often offer remote access to their historical files, and do so with remarkable clarity and quality. The newspaper files of New Zealand, for example, are so immaculate and easy to search that reading them remotely from nearly seven thousand miles away often feels like taking the paper pages in hand.

When considering a character like Professor Risley and his Imperial Japanese Troupe, this technological revolution is enormously useful. It helps cut through decades of accumulated misinformation and myths. It allows me to rely mainly on primary sources, instead of what other people have written, and to quote extensively from Risley’s contemporaries, in their wonderfully colorful nineteenth-century voices. And it creates an almost voyeuristic thrill. Because Risley survived by generating publicity and running advertisements in newspapers, it becomes suddenly possible to track his movements at an extraordinarily granular level, on multiple continents and through the fourth dimension of time. In a sense, online databases are rather like the new satellite, sonar, and undersea robotic technologies that have made the world’s oceans increasingly transparent, allowing discovery of more and more valuable treasures and old wrecks hitherto hidden beneath the sea. By searching through vast seas of newspapers and magazines on multiple continents, through multiple languages, the movements and actions of people over a century ago become visible in ways they never imagined, to degrees they might even have found embarrassing. In the nineteenth century, after a failure or scandal, simply changing towns was often enough to allow one to start anew; not so any more. We can now view the past movements of people almost as if we are omniscient gods, looking down on humans from outer space.

*

Many people have aided me in the production of this book, and they deserve more thanks than I can adequately provide in this preface.

For agreeing to read part or all of my manuscript and provide valuable comments, many thanks to Ricard Bru i Turull, Jonathan Clements, Fiammetta Hsu, John Kovach, Aya Mihara, Leonard Rifas, and Mark St. Leon. Aya Mihara performed the especially arduous task of meticulously checking detailed references in such a complicated story and making many valuable suggestions; she also helped in the identification of CDVs (“carte de visites,” or a type of card-mounted photograph), and I am particularly grateful to her. For much other useful assistance in research and assorted favors, thanks and a special tip of the hat to: Nobuko Aoki, Norihiko Aoki, Vivien Burgess, Yen Mei Chen, Mimi Colligan, Peter Field, Bernard Gory, Jacques Gordot, Andrea V. Grimes, Allister Hardiman, Yin-chiu Hsu, Nanae Inoue, Yuki Ishimatsu, Dominique Jando, Yumiko Kawamoto, Lytfa Kujawski, Raymond Larrett, Raymond Lum, Mitsunobu Matsuyama, Motoka Murakami, Judith Olsen, Daniele Rossdeutcher, Robert Sayers, David W. Schodt, Laurence Senelick, Mikey Sullivan, Kiyoyuki Tsuta, Jane Walsh, and Matthew W. Wittmann. My mother, Margaret Birk Schodt, was a constant inspiration. Also, many thanks to the employees of the following libraries and organizations: the Bibliothèque Nationale de France; the British Library Newspapers; the California Historical Society; the East Asian and Bancroft Libraries of the University of California, Berkeley; the Fukushima Prefectural Library; the Harvard Theatre Collection of the Houghton Library; Hong Kong University’s Hong Kong Newspapers and Special Collections Department; The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art; the Mitchell Collection, State Library of New South Wales; the Oregon Historical Society; the Philadelphia Library Company; the San Francisco Performing Arts Library and Museum; the San Francisco Public Library (especially the Inter-Library Loan folks and the History Center and the Schmulowitz Collection of Wit and Humor); the Society of California Pioneers, the Yokohama Archives of History; and the Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library.

Except for the names in this credit list, which are listed in Western order for alphabetical consistency, Japanese names in the main text are listed in Japanese order of surname first and given name last. All maps and translations are the responsibility of the author, unless otherwise noted. Bruce Rutledge, of Chin Music Press, kindly served as the text editor and was so gentle and skillful that it was entirely painless. Finally, without the support of my good friends at the intrepid Stone Bridge Press—including the wonderful designer Linda Ronan and especially Peter Goodman, the founder and publisher—this book would never have been possible.

Frederik L. Schodt

San Francisco, 2012