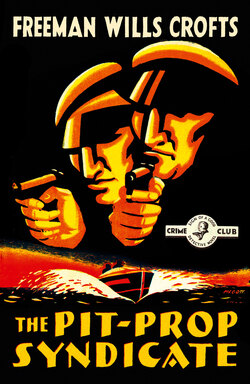

Читать книгу The Pit-Prop Syndicate - Freeman Wills Crofts - Страница 6

INTRODUCTION

Оглавление‘MR CROFTS is the master of this austere, unsensational but—to minds who enjoy stubborn but logical reasoning—enthralling type of puzzle fiction.’

This assessment of Freeman Wills Crofts’ output by author and publisher Michael Sadleir in a BBC radio review of an early Crofts title was both accurate and very fair. In fact, it remained true for the rest of Croft’s career; and, indeed, to this day.

To Crofts belongs the shared honour of inaugurating the Golden Age of Detective Fiction. The publication of his first novel, The Cask, in 1920 launched that celebrated era in the history of crime fiction. Christie’s The Mysterious Affair at Styles is usually bracketed alongside it, although, to be strictly accurate, its 1920 publication was only in the US, with UK publication delayed until January 1921.

The Cask, in many ways, created the template for a Crofts detective story: a meticulous investigation carried out with painstaking attention to detail and focusing, for the most part, on alibis and timetables. The reader is at the detective’s side throughout the book as he doggedly pursues even the slightest clue, forcing it to give up its secret. Having achieved considerable success with The Cask, Crofts remained faithful, to a greater or lesser degree, to this type of story for the rest of his writing career. And so it is with The Pit-Prop Syndicate: there is little action, and the only excitement is of the cerebral kind. But this did not prevent Crofts becoming one of the ‘Big Five’ of Golden Age detective fiction, alongside Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, R. Austin Freeman and H. C. Bailey. More than half a century after its publication, the author, reviewer and crime fiction historian, Julian Symons, chose The Pit-Prop Syndicate for inclusion in his list of ‘The Hundred Best Crime and Mystery Books’, compiled for The Sunday Times in 1957.

Crofts followed his first novel with a more traditional country house mystery, The Ponson Case in 1921; his third book, The Pit-Prop Syndicate, appeared in 1922, and The Groote Park Murder, set partly in South Africa, followed the year after. In each of his first four books an official police investigator carries out the investigation: Inspector Burnley in The Cask; Tanner in Ponson; Willis in Pit-Prop; Vandam in Groote Park. This experimentation finally brought about the emergence of Crofts’ signature detective, Joseph French, who made his debut in 1925 in Inspector French’s Greatest Case and subsequently appeared in all of his remaining books. The earlier incarnations were not as immortal as Inspector French, although they differ little from the eventual series character.

In a 1932 letter to his publisher Crofts gave a description of French, notable only for its vagueness, which, as we will see, was intentional:

‘… rather stoutish man of slightly below middle height, blue-eyed, with a pleasant, comfortable, cheery expression … not distinguishable in dress from any other civilian … suave and pleasant … dressed in an ordinary lounge suit.’

In clarification he goes on to explain that:

‘I have tried to make French an ordinary man, carrying out his work in an ordinary way. It seemed to me that there were enough “character” detectives, such as Colonel Gethryn, Philo Vance, Poirot, etc. Thus he has no special characteristics except being thorough, painstaking, persistent and a hard worker.’

Much the same traits can be applied to Willis, and indeed to the Inspectors in Crofts’ earlier books. Continuing a pattern he was to follow for the rest of his career, Crofts avoided the use of a Watson character and Inspector Willis carries out most of the Pit-Prop investigation on his own. Usually the Watson character accompanies the detective throughout the investigation, describing all that he (the only female Watson of note being Gladys Mitchell’s Laura Menzies, sidekick to Mrs Bradley) sees and hears; the Watson’s more important role is as reader-substitute, acting as the admiring audience while the Great Detective explains his deductions. Willis—and later French—has little need of such a device, as the detective himself shares his thought processes directly with the reader.

Crofts’ great strength as an author was the painstaking construction of his plots rather than character delineation. In his 1937 essay ‘The Writing of a Detective Novel’ (included in the recent Detective Story Club reprint of The Groote Park Murder) he notes:

‘If we are lucky we shall begin with a really good idea … it may be an idea for the opening of [the] book: some dramatic situation or happening to excite and hold the reader’s attention.’

Although the premise which precipitates the mystery in Pit-Prop can hardly be considered either dramatic or exciting, its very ordinariness—the inexplicable circumstances of the exchange of the numbered brass-plate on a ‘Landes Pit-Prop Syndicate’ lorry—is sufficiently intriguing to engage the reader’s curiosity. And even before we read of this minor mystery which first engages Merriman’s attention, our curiosity is aroused by a paragraph of foreshadowing, early in the first chapter:

[Merriman] did not know then that this slight action, performed almost involuntarily, was to change his whole life, and not only his, but the lives of a number of other people of whose existence he was not then aware, was to lead to sorrow as well as happiness, to crime as well as the vindication of the law, to … in short, what is more to the point, had he not then looked round, this story would never have been written.

The early chapters of the novel are somewhat reminiscent of the famous Erskine Childers’ 1903 spy novel The Riddle of the Sands. In that book two friends, while ‘messing about in boats’, notice something potentially sinister which demands further investigation. In the case of Riddle it is a matter of national and international security; in Pit-Prop it is of a criminal nature. But what crime exactly? That is the mystery facing Merriman and Hilliard and Willis; and Crofts manages to keep the reader equally mystified about this for most of the novel. Clearly Crofts was a fan of the sea and many of his titles reflect this: The Sea Mystery, The Loss of the ‘Jane Vosper’, Found Floating, Mystery in the Channel, Mystery on Southampton Water. His casual use of unexplained sailing terminology in Chapter III—‘flush-decked’, ‘a freeboard’, ‘binnacle’—is further indication of this.

Another personal interest merits a brief mention in the previous chapter when the ‘gentle hum of traffic made a pleasant accompaniment to their conversation [Merriman and friends at their club], as the holding down of a soft pedal fills in and supports dreamy organ music’. This unusually poetic simile reflects Crofts’ interest in music: he was a church organist and choir-master in his leisure time.

While Crofts’ undoubted strengths lay in the intricate construction of his plots, it must be acknowledged that his emotional passages are less than compelling. Even knowing that Chapter X was written almost a century ago does not make the love scene between Merriman and Madeleine any more convincing or less embarrassing, as these excerpts demonstrate:

She covered her face with her hands. ‘Oh’, she cried wildly. ‘Don’t go on. Don’t say it.’ She made a despairing gesture.

‘What a brute I am!’ he gasped. ‘Now I’ve made you cry. For pity’s sake!’

‘Madeleine,’ he cried wildly, again seizing her hands, ‘you don’t—it couldn’t be possible that you—that you love me?’

There can be little doubt that Crofts had read Fergus Hume’s best-selling The Mystery of a Hansom Cab. This inexplicably popular book, published in 1886 in Australia and the following year in the UK, went on to sell over half a million copies. It is directly referenced in Chapters XIII and XIV of Pit-Prop after the discovery of a murdered man in the back of a London taxi, circumstances reflecting closely a similar scene in which the Hansom corpse was found a quarter-century earlier. And echoes of his own first novel can be detected in Chapter VII when the detective duo put a cask to investigative use. Spending many hours inside the ‘confined space and inky blackness of the cask’ is a severe test of the dedication of the pair to their detective adventure.

In true Golden Age fashion we have three maps/diagrams. A page of Chapter XX is devoted to the drawing of a railway line and a discussion of train times; much of that chapter is concerned with rail travel—a real Crofts trademark. Although the map adds little to our understanding of the plot and neither of the two earlier maps is vital to the solution of the mystery, true Golden Age fans are always pleased to find a diagram in a story, let alone three of them!

It has to be acknowledged that the legality of some of Willis’ actions in pursuit of his investigation leaves much to be desired. Tapping phone lines, picking locks, capturing fingerprints (even when the site of one particular fingerprint is very ingenious) are questionable actions, to say the least. And that taboo element of Golden Age fiction, the secret passage, is also evident—although as the solution to the crime does not depend on its existence it does not contravene any ‘rule’ of fair play.

A minor mystery for modern readers concerning The Pit-Prop Syndicate might be the title. A ‘pit prop’ is a wooden beam used to support the roof of a mine, and in the days when mining was a major industry the provision of such items was an important and lucrative business. While words such as Murder and Death did not feature as frequently in the titles of crime novels at this point in the genre’s development as they were shortly to do, The Pit-Prop Syndicate is, by any standards, a very unexciting title.

Title aside, however, Crofts’ third novel offers a blend of thriller and detective story, roughly divided between Parts One and Two of the novel. Both sections show Crofts putting his engineering training to imaginative use, and are a foreshadowing of the enormously popular Inspector French novels that would soon follow.

DR JOHN CURRAN

October 2017