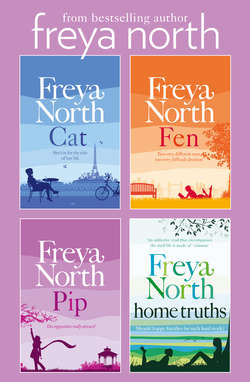

Читать книгу The McCabe Girls Complete Collection: Cat, Fen, Pip, Home Truths - Freya North - Страница 15

SETTING THE WHEELS IN MOTION

ОглавлениеWednesday. The English Channel. 10 a.m.

How strange. On the ferry’s deck, Cat McCabe, who has fantasized about following the Tour for years, who has recently acknowledged that a change of country – if only for three weeks – would be a sensible and constructive option, has found that she is wishing she’d stayed put, that she could be back at home. She is very nervous, convinced she’s bitten off more than she can chew and fears she might choke. Oughtn’t she just to watch the Tour on Channel 4, in privacy at home as she always has? She could be on her settee, with a nice cup of tea, proclaiming aloud that the presenters, Phil Liggett and Paul Sherwen, should have their own TV series. Or run for Parliament. Or come over to her flat for coffee and a chat.

Maybe it would just be better if I had no interest in cycling at all.

Cat experiences lurches of homesickness when the white cliffs start to shrink. Wafts of the panicky emotion gust through her more strongly than the buffets of sea air which, she kids herself, are the sole cause for her smarting eyes. Having enjoyed umpteen imaginary conversations with real or fictitious characters in the months leading up to this day of departure, Cat suddenly realizes she has no idea where she’ll find the confidence to approach such people in the flesh.

I haven’t the balls. Quite literally. They’ll take the piss, surely. Me – British and female – amongst all of them.

Furthermore, she’s had her hair cut yesterday and, though merely a variation on her common theme of shoulder length plus fringe, she doesn’t like it and feels self-conscious. The blasts from the sea breeze seem alternately to blow and suck her hair into configurations she cannot see but is convinced are queer and most certainly unattractive. She gazes at the white cliffs for as long as she knows she can really see them, trying very hard to ignore the fact that she now feels seasick as well as homesick, attempting to focus instead on France France Tour de Bloody France and all it is going to do for her sanity, her career and her future.

When does the English Channel become La Manche? Soon? Already?

Only a good few moments after Dover has unarguably disappeared can Cat finally turn her attention from inward and England, forward to France and, for the time being, her immediate surroundings. She turns her back on all she is leaving and faces the direction of travel, France, forwards, ever onwards. She glances around the deck, simultaneously keen for someone to recognize her yet desperate that no one will.

It’s strange. I suppose I presumed the entire ferry would be peopled by those going to the Tour – that we’d all be recognizable as a club of sorts and, of course, that there would be this wonderful familial feeling amongst everyone. And yet now I’m here, I have no idea who is who. Most of the passengers look like standard holidaymakers. But what specifically distinguishes cycling followers? I don’t even see any of the stalwart, anoraked, club cycling crowd that spend their Sundays traipsing the Trough of Bowland or struggling in Snowdonia. I mean, there’s a small group over there in tracksuit bottoms who look young and sporty – but they’re just as likely to have hired a villa in Brittany.

Though Cat half wants to be recognized – as a cycling aficionado of the non-anorak genus if not as the sports journalist she is hoping to become – the other half of her is quite content to be invisible. She ventures inside the ferry and queues for rubber sandwiches and plastic coffee, trying not to scan the tables too obviously for that elusive quiet spot, a hiding place. She spies one that might suffice and heads for it, looking at no one and trying to look nonchalant herself despite her bulky rucksack and wobbling tray.

‘The Prologue will definitely be Boardman.’

The sentence causes Cat to slow up instinctively.

Brilliant! I think it’ll be Boardman too!

‘I’d say Jawlensky,’ comments another voice.

No, I think your colleague and I have it with Boardman. And it’s Yav-lensky.

‘Yav,’ says the first voice.

‘Hey?’

‘Yavlensky.’

See!

‘I hardly think my pronunciation will make much difference to the outcome. Jawlensky is going to take the Prologue from Boardman, thus ending his reign.’

‘Bollocks.’

Yeah – bollocks!

Cat aborts her journey for a place squeezed in at a table neighbouring that of the two men discussing the Prologue Time Trial, which forms the inauguration of the Tour de France. She eavesdropped as subtly as she could, listening without looking.

‘Did you go to the Giro?’ the man au fait with Russian pronunciation asks the other.

‘Nah. Actually, I haven’t covered a race since the Tour of Britain.’

But I was there! Cat starts to herself with pleasure superseded by dread. Oh God, who are you though? I did the whole of the Tour of Britain for Cycling Weekly – up and down the UK for seven days. Did I meet you? Have you already seen me today and decided not to say hullo? Or seen me, perhaps, hut not recognized me at all because you didn’t notice me on the Prutour?

She regards her sandwich as if staring at food might nourish her nerve.

Do I dare turn around? Nonchalantly or with intent? Brazenly or with contrived innocence?

She scrunches her hands into fists, digging her nails reprimandingly into her palms.

Come on Cat, get a grip.

She grips herself hard.

Right, I’ll turn around, pretend I’m looking for a – for a clock – then I’ll shift my gaze and say, ‘Oh hi! Weren’t you on the Tour of Britain?’ Or maybe just regard him like I know I know him but can’t figure out where from, and then snap my fingers and say, ‘Tour of Britain?’ Or maybe—

‘Shall we go on deck?’

No! Wait! I haven’t turned round yet.

‘Yeah, sure – another beer?’

‘Yeah – start as we mean to carry on.’

‘You’re telling me! Come on, let’s split.’

Wait – I’m going to turn around right now and say, ‘Hi, I’m Cat McCabe, I’m reporting for the Guardian – I think I met you at the Tour of Britain.’ See – now!

But it is too late. The backs of two men are all Cat sees and she cannot deduce whether or not she has met one of them.

Tomorrow. I’ll find them tomorrow and I’ll introduce myself then. And if they ask when and how I arrived, I’ll feign surprise that ‘No way! I was on that ferry too!’

Oh God.

Me, myself and I for over three weeks in France.

Wednesday. Hôtel Splendide, Delaunay Le Beau. 2.30 p.m.

Rachel McEwen banged her clenched fist down on the concierge’s counter. Her treacle-coloured hair was loose and rather wild and her eyes were ablaze with fury and indignation.

‘Mademoiselle?’ said the clerk, with a superciliously raised eyebrow that made Rachel clench and reclench her fist as if she was about to aim a blow.

‘Look,’ Rachel said in a cold, courteous voice that served to accentuate her outrage more descriptively than any physical attack, ‘it is not my room I want changing, but room 46. I am not having one of my riders sleeping on a camp bed in a cramped room with crap curtains.’

‘Wait,’ said the clerk witheringly, dropping the one eyebrow and then twitching the other, along with a slight smirk, as he disappeared. He returned with his smirk and also a smartly dressed woman.

‘Good afternoon,’ said Rachel. ‘I was trying to explain to your colleague that I find it unacceptable that there is only one decent bed in room 46. I have two riders sharing and I will not have either one sleeping on a camp bed.’

‘Miss?’ the manageress, as she transpired to be, enquired.

‘Mc–Ewen,’ said Rachel briskly, breaking her name as she only ever did when she was deadly serious and very annoyed. ‘I am soigneur for Zucca MV.’

‘Zucca!’ the lady marvelled quietly, flushing slightly. ‘Miss McEwen, I am terribly sorry. I will of course rectify this problem immediately.’ She rustled through an index file, tapped officiously at a computer and gabbled at the clerk who scurried off, the smirk wiped from his face. She raised an eyebrow in a much more impressive way than her male junior. ‘Room 46 – Massimo Lipari? Ah, and Gianni Fugallo – a good domestique.’

Rachel smiled.

Here’s the link. Here’s the bond. A passion shared is a problem solved.

‘I shall put them in room 40 – I don’t know how this could have happened and I apologize.’

‘Thank you,’ Rachel said, the relief in her voice softening her tone, her hair no longer seeming wild but, rather, merely unkempt through stress and a devotion to priorities in which concerns for coiffure were too petty to feature.

‘Miss McEwen,’ the manager cleared her voice, ‘if it is possible, an autograph? From Massimo? For me – Claudia?’

‘Bien sûr,’ Rachel nodded.

Funny how I know just enough idioms in French, Spanish, Italian – even Portuguese and Flemish – to get by! If we ever raced in Latvia, no doubt I’d learn the lingo for ‘no problem’, or ‘cheers’, or ‘put your hands away I’m not interested in sleeping with you’.

Rachel marched back to the lifts, back to room 46 and told a dejected-looking Gianni not to worry. Then she made two trips to room 40, transferring the riders’ bags and belongings while they sat on the one good bed, resting their legs and feeling the minutes ebb away and the Tour loom ever nearer.

Wednesday. Hôtel Splendide, Delaunay Le Beau. 5.30 p.m.

‘Yes?’ said the manageress to, remarkably, another British girl.

‘MissMcCabe,’ Cat strung in a rushed whisper, looking around the foyer, her heart still racing from the excitement of spying the cars of three different teams in the hotel car park, emblazoned with logos and crowned with the bike racks.

Cofidis! Banesto! Zucca MV!

‘Ah, Miss McCabe, your room is on the fifth floor. Number 50.’

When Cat arrived at the lifts she grinned, for there, as in all races, regardless of prestige, a list of the teams and their rooms was pinned unceremoniously.

Jesus – what a perfect, God-given sandwich I have become!

Temporarily flabbergasted, Cat scanned the list over and again, pinching herself that what she saw was correct.

It says so! Massimo Lipari and Gianni Fugallo directly below, Jose Maria Jimenez directly above. If Jimenez and Lipari want to vie for pin-up of the peloton, they can always meet half-way at room 50 and let me be the judge!

The fact that room 50 turned out to be rather small, with the teak veneer fittings and meagre chewing-gum-grey towels typical of a sub-2-star hotel, was of no consequence to Cat.

I’m here in France surrounded by the boys!

Wednesday. Hôtel Splendide, Delaunay Le Beau. 11.29 p.m.

Stefano Sassetta is delighted. Thanks to Rachel, his soigneur, he does not have to share a room. He had a great training ride this morning and is confident he will attain peak form during this first week, be invincible in the sprints and start hoovering up bonuses for the points in the green jersey competition. His thighs feel good and, after Rachel’s incomparable massage and Stefano’s lengthy scrutiny in the bathroom mirror, they look sublime to him. Stefano has been zapping through the television channels. His French is poor so he continues to flick the remote control, stopping awhile at MTV, enjoying a few minutes of boxing on Eurosport before it becomes tractor racing or dominoes, or some commensurately poor excuse for a sport. On he zaps. He is tired. He should sleep. But he is too psyched. If his manager came in and suggested a night ride, he’d be on his bike in a flash. He feels powerful and proud. And now he is delighted, for, two channels on from Eurosport, a porn movie is in its throes. Now he’ll be able to sleep. Masturbation is a great idea. Masturbation is better than sex – no energy wasted, as an ejaculation uses only sixty calories. No energy thrown away on pleasuring anyone but himself.

Thursday. Delaunay Le Beau. 10 a.m.

In the timescale of the Tour de France, Thursday is the dawn of two days of medicals for the riders, accreditation for the journalists and press conferences for both.

The previous evening, though Cat had tried valiantly to stay awake and recline demurely on her bed reading, neither Jose Maria Jimenez or Massimo Lipari had come to see her. She had woken in the early hours, dejected and still clothed.

As if they would have come to my bloody room.

Feeling a little foolish, she had crawled under the bedcovers, still clothed, for a few more hours of exhausted sleep.

Now, showered, changed twice, breakfasted and disappointed that there were no riders in sight, Cat left the hotel; the whirlwind of butterflies in her stomach at odds with the balmy climate outside. The trees, lampposts and road signs in the town of Delaunay Le Beau, which was hosting the Prologue and housing the Tour entourage, were bedecked with arrows pointing the colour-coded way for anyone who had anything to do with the Tour de France. For Cat, to follow the green pressé arrows was like being led on a treasure hunt.

Somewhat circuitously (the prerogative of the town’s chambre de commerce), the route took her past picturesque squares, the main shopping area, the university and the hospital – anyone who was anything to do with the Tour de France was to be subliminally persuaded that Delaunay Le Beau was a pretty town with excellent facilities. For Delaunay Le Beau, paying to play host, the Tour meant Tourism. Eventually, she arrived at the Permanence, an ironic title for the eternally temporary headquarters of the Société du Tour de France. In Delaunay Le Beau, it was housed in the grandiose town hall.

Cat McCabe had no idea what to expect – from Thursday, from the Permanence, from anything at all. For Ben York, however, an anxious female chewing her lip while her eyes darted as if on a pinball course was certainly not what he expected to see when he escorted his Megapac riders to the Permanence for their physical assessments. His groin gave an appreciative stir and his lips a flit of a smile at the sight of her. He felt almost privileged, as if spying the first swallow of summer before anyone else.

Here comes Cat, trying to saunter down the sweeping staircase of the town hall, hoping her grip on the banister seems nonchalant. She has been queuing for her accreditation in a vast room throbbing with strangers. Now she is wearing her green pass and she displays it with pride; it hangs from her neck and is as precious to her as pearls. It is the reason for her heightened state of excitement and the resulting lack of composure. It is her access to the real Tour de France; this year she has backstage privileges. Last year, and the years before, the cyclists were one step removed behind her TV screen.

I’m a journaliste. See? It says so: Cat McCabe, Journaliste, Le Guardian. That’s me. That’s what I do and who I am.

Ah, but Cat, how many journalists hover half-way down a staircase, fixated by the middle distance and gripping the banister with both hands?

I hate stairs. Please emphasize the ‘eeste’ – journaliste sounds far more delicious, much more prestigious than the English pronunciation.

All right, Cat McCabe, journaliste, walk on down the stairs and do your thing.

See her taking the stairs slowly, trying to absorb everything that is going on around her without looking quite the goggle-eyed devotee that she in fact feels?

I hate stares. Someone down there is looking at me. Keep walking. Oh Jesus! It’s Luca Jones! I’m going to have to stop again. That’s the medical check. Shit shit – what should I do? What am I allowed to do? What do journalists-istes do? Dictaphone? Yes, of course I have it with me. Ditto notepad. I have everything a journalist on the Tour de France could possibly need. But what I have most in abundance is nerves.

Establish eye contact with Luca, Cat. Why don’t you give him a smile? You needn’t say anything, but a smile today might mean recognition tomorrow, perhaps another smile the following day and huge familiarity thereafter.

I know. I know. I’m metaphorically kicking myself already for being so stupidly shy. But I have over three weeks. I won’t go home till Luca and I are on first-name terms.

We’ll hold you to that.

Don’t. Oh! It’s Hunter Dean! Dark, handsome and utterly Hollywood.

Hunter appears from his medical and beams at the loitering media consisting of six or seven tall men. Hunter really is the personification of his mission statement. Tipping his sunglasses up on to his head, courteously, he permits the clutch of journalists to surround him and systematically attends to all questions and answers them well, with considered replies and great charm.

Fuck fuck!

Cat is in a quandary. She has reached the bottom of the staircase and is so overcome by her proximity to her heroes that she feels much more like running from the building and hyperventilating somewhere in private, than in doing her job extracting soundbites.

What should I do?

They won’t bite.

Shall I just breeze up to the group and stick my dictaphone under Hunter’s mouth?

She ventures over and does just that. It’s the kind of thing a journalist does, Cat deduces from the bouquet of hand-held recording equipment already thrust at Hunter’s lips. She stares unflinchingly at the Megapac logo on the breast of Hunter’s tracksuit top. Hunter speaks, his voice pulls Cat’s gaze to his face while her dictaphone scrounges for soundbites with the best and rest of them.

Hunter’s lips. God, he has a beautiful neck.

Six male journalists stare at Cat who is incapable of controlling a creeping blush.

Oh shit, I didn’t just say that out loud, did I?

Cat nods earnestly at whatever it is that Hunter is saying. She praises gods of all creeds for the invention of the dictaphone because whatever he is saying, that the current thrill of it all prevents her from hearing, she can listen to later anyway. She focuses hard on the bridge of Hunter’s nose, to discipline her desperate-to-flit gaze.

‘Initially, Megapac may be an unknown quantity in terms of the Tour de France,’ Hunter is expounding, ‘but we’ll be the team on the tip of y’all’s tongues by the end – that I can assure you. You can quote me on that. We’re the best thing to happen in American cycle sport since Greg LeMond and Lance Armstrong.’

‘Bonne chance!’ Cat surprises herself by responding unchecked, anticipating that Hunter might very well start to sing the Star Spangled Banner or quote the Constitution.

‘Hey, yeah, right!’ Hunter responds.

With a wink! Did you see that? A wink! I’ve died and gone to heaven. Does a wink come out on a dictaphone?

‘Cute,’ Luca nudges Ben, out of Cat’s earshot. Ben gives Luca an exasperated look that prevents him having to agree and thereby present himself as a contender. Fortuitously, Luca is called through for his medical and Ben can regard the lone female with a certain private pleasure while Luca creates a diversion. He sees her redden as she focuses on Luca.

Bastard boy racer, he frowns to himself, but why on earth wouldn’t she blush? There’d be something wrong with her if she didn’t. And, anyway, it’s proof to me that she’s a healthy, sexual person. And that’s good.

A couple of journalists call greetings to which Luca replies with the victory sign before disappearing into the open arms of the Tour’s medical team.

I should have called out something, Cat reprimands herself. Wouldn’t my voice have stood out, made him stop and perhaps notice me?

Cat looks a little forlornly at the space on the bench Luca has left. Her gaze shifts to the right and clocks a nice pair of Timberland boots, good legs clad in black jeans, a white shirt. Her eyes travel automatically upwards, over a strong neck, ditto chin, to a pair of just parted lips. She finally alights on very dark brown eyes which won’t let her go. She notes a handsome face enhanced by a wry smile, crowned by dark hair cut flatteringly close to the head and quite strikingly flecked through with grey. Momentarily, Cat wonders who he might be. But she knows he’s not a rider so her interest wanes.

Anyway, I have to go. I have to find the salle de presse. I’m working. It’s my job.

Ben watches her leave, rather gratified by the fact that he’ll see her again over the next three weeks.

Thursday. Salle de presse. 1 p.m.

Starving hungry, Cat’s appetite disappeared on entering the press room. Dread instead filled her stomach until fear was a hard lump in her throat and panic was a terrible taste to the tongue. She felt immediately that she had been transported back to Durham University, that she had just entered a vast exam hall and was ten minutes away from the start of her finals. The comparison was apposite but, as in an anxiety dream, disconcertingly twisted too. Noise. Too much of it. You can’t sit the test of your life amidst such a din. There again, you wouldn’t really sit your finals in northern France, in an ice rink requisitioned by the Société du Tour de France.

What had happened to the ice was initially of little relevance for Cat. Rather, she was transfixed by line upon line of connected trestle tables on which, at regular intervals, an army of laptops were positioned, gaping like hungry mouths eager to gobble down the information in any language as long as the topic was cycling. At the front and to either side, a brigade of industrial-sized televisions was mounted on tall stands, surrounding the journalists and perusing the scene like phantasmagorical invigilators.

If I’m not at Durham University, then I’m in a George Orwell novel or a Terry Gilliam film. Am I really at the Tour de France? It’s all so vast – anonymous, even. What on earth am I meant to do now? Where should I sit? This is my workplace for the next three days, how am I ever going to be able to concentrate?

Cat felt much sicker and far less steady on her feet than she had for any exam, or even on the ferry. But she made it to a space on a run of trestle conveniently close and which, to her relief, had an expanse of at least three metres between where she set up and the next journalist.

I’m in Babel. Did no one say hullo in Babel? Isn’t my pass enough – do I need a password too?

After a quick, furtive scout around, Cat plugged in her laptop, positioned her mobile phone near by and fanned out a selection of the booklets she had been given at accreditation.

See, now my workspace looks no different from any of those around me. I’m one of them, now. So, now someone should say hullo. I’m going to busy myself I’d like to scrutinize this one: ‘Les hotels, les equipes’ – see if any of my other hotels during the Tour might house teams too. Better not – that’s something I can look forward to doing later tonight when I’m in my room pathetically deluded that Jimenez or Lipari might come and find me.

I’ll start by flipping through this booklet – ‘Les régions, la culture’. Fuck, it’s all in French. I’ll just skim the pages as if I’m speed reading – oh God, but if I do, they might presume I’m fluent and come up jabbering away at me. PR packs from the teams. That’s better. I’ll start with Zucca MV.

She was staring at photos of the team when her mobile phone rang, causing her to jump and fumble with the handset.

‘Hullo?’ she whispered, her hand guarding her brow, her eyes cast unflinchingly down towards the keys on her laptop.

‘Bonjour!’ boomed Django so loudly that Cat glanced around her expecting to find the entire press corps listening in, knowing it wasn’t work, that she was but a pseudo journaliste. However, her presence, let alone that of Django’s voice, was obviously still undetected. Now she was relieved.

‘Hullo,’ she said, ‘Django.’

‘How are you?’ he asked, slurring his words in his excitement. ‘Where are you? What’s happening? Keeping a decorous distance from all that lycra, I do hope?’

Though she’d hate herself for it later, Django’s enthusiasm irritated Cat.

I’m working. This isn’t a holiday. Take me seriously.

Ah, but don’t deny it is a pleasure for which you yourself cannot believe you are being paid.

I bet nobody else’s uncles are phoning them.

Well then, you should pity them.

‘I’m fine,’ Cat said quietly, ‘but busy – press conferences, deadlines – and then some.’

Haven’t actually been to a press conference. My first deadline is tomorrow.

‘And the people?’ The pride in Django’s voice caused Cat’s eyes to smart. ‘Are they nice? Have you made friends? And the riders, girl – have you met and married?’

‘Oh,’ Cat sighed, swiping the air most nonchalantly, unaware that it was a gesture wasted on Django, ‘loads – great. Everything.’

‘Well, I’ll phone again,’ Django said gently, sensing her unease. ‘Just had to make sure that you’re really there – now that I hear you, I can continue with my jam-making. I’m trying damson and ouzo. I thought an aniseed taste and an alcoholic kick might be an interesting addition to an otherwise relatively mundane preserve. There’ll be a jar, or pot, probably plural, awaiting your return.’

Django’s culinary idiosyncrasies suddenly touched Cat. She closed her eyes and listened. It was like a voice not heard for a long while and yet its immediate familiarity was so comforting it was painful.

‘Thanks, Django,’ Cat said, smiling sadly, ‘but I have to go. Bye.’ She switched off, stared hard at the phone and forced herself to switch off. Back she was, in the formidable ice rink.

Too many people were smoking too many cigarettes. A man with a handlebar moustache was smoking a cigar. A large one.

He looks like an extra from a spaghetti western. What do I look like? A journaliste? I don’t think I’m noticeable at all. Do I want to be? And I haven’t done any work, I haven’t even switched my laptop on.

And there’s the Système Vipère press conference in ten minutes.

Good, I can get out of here.

Thursday. Team Système Vipère press conference. 1.30 p.m.

Cat just sits and stares. Her physical proximity to Fabian Ducasse is causing her to hold her breath. It is as if she fears that if she doesn’t, unless she keeps utterly still, he’ll disappear and all of this will have been some tormenting apparition. And what a shame that would be, with Fabian currently smouldering at the press corps, his mouth in its permanent pout, his eyes dark, his focus hypnotic. He is taller, broader, than Cat had previously assumed from television appearances. His skin is tanned, his hair now very short and emphatically presenting his stunning bone structure. His cool reserve, the aloof tilt of his head draw all present to his every move, his every word, at the expense of his equally hallowed team-mates sitting alongside. The conference is conducted in French and fast and, to Cat, the very timbre impresses her far more than the specific words she can pick out and string, if not into a sentence, into the gist of one. The room is charged. Or is it? Is it Fabian Ducasse’s doing? Or is it just Cat?

On the platform at one end of the conference room, Jules Le Grand has flanked himself with Fabian Ducasse, Jesper Lomers, Carlos Jesu Velasquez and the youngest member of the team, Oskar Munch, whose first Tour de France this is. Oskar appears as awestruck as Cat – if they caught sight of each other they could exchange empathetic gazes. This, though, is unlikely to happen in a room of at least two hundred people.

For Oskar, I’d like to write a piece about domestiques, the unsung heroes who work away selflessly for the greater glory of their leader, their team.

Carlos is about to speak.

Fuck, all in bloody Spanish! Mind you, he’s a man of few words and his grunts are unilaterally understandable. He’s probably just been asked if he feels in any way compromised riding for a French team. That shrug-mutter I take to mean ‘Amigo, I am doing my job – a fine company wishes to employ me, to pay for my skill – where’s the conflict or compromise?’ Ah Oskar, someone’s asked you your ambition for the Tour.

‘Paris!’ Oskar announces as if to an idiot.

Shall I ask him about preparation? How well he knows the route? How much is a technical, theoretical study of alpine gradients and Pyrenean cross-winds, how much is physical familiarity with specific climbs? Oh, and mental attitude – will his spirit ensure entry into Paris even if twenty-one arduous days have broken his body?

Yes, Cat. Go for it.

Me? No. Maybe tomorrow.

This is Oskar’s press conference today.

In twenty-one teams, there are approximately six domestiques in each. I’ll have my pick.

You’re contradicting yourself – you just said how much you respect domestiques as riders in their own right. I think you should go for Oskar.

This is my first press conference. Give me a break.

The Guardian newspaper is giving you your break, remember.

Thursday. Salle de presse. 2.30 p.m.

There’s a lot of bad typing in the press corps and a quite startling array of awful footwear, thought Cat on returning to the press room and making it back to her seat without anyone acknowledging her presence, which, in truth but to her surprise, caused her a little consternation. All around her, mobile phones were bickering to outdo each other with terrible jingles in place of regular ringing tones.

Cat opened a new file in her laptop and plugged an earpiece into her dictaphone, swooning slightly and smiling broadly at Hunter’s American tones. The blank screen was far too intimidating so, etching an expression of utter concentration over her face, Cat looked up and around her, as if deep in thought rather than analysing the particulars surrounding and distracting her.

I mean – look at him, very thin and pale, wearing too short shorts, no socks and shiny black brogues. And that one looks like something out of a Brothers Grimm fairy-tale in those suede pixie boots. And with toes like that, that man there should certainly refrain from putting them on public display.

Cat placed her fingers rather primly on the keys, then took them off again. What to write, what to write? What on earth was everyone else writing?

I don’t want to start – not that I know where to. I’m surrounded by two-digit keyboard bashing and inefficient finger knitting – how can they manage entire articles using the index finger of their left hand and the third finger of their right? There again, I can touch-type – and fast – but I can’t write a bloody word.

Cat was subsumed by an illogical fear that, as soon as she started typing, there’d be silence and all eyes would be on her, assessing how fast she types, how she types, what she writes, even what shoes she wears. She stared at her screen then glanced around her, momentarily bolstered by the fact that though everyone’s screens were on view, it was impossible to discern what they’d written, never mind in what language. Her fingers hovered and then alighted softly on the keys. She cocked her head, as if Hunter had said something of supreme interest, and allowed her fingers to skitter randomly over the keyboard.

akdjoii sdiuej fdiknvoiq=- jdoaign kdjlau SODIJA L.upoadj lkduflakdkruoqemma d OKLAKEUR .kdug; ae#q, dkafp9cekjr9 diuarslkqjwlfreO dpsofiqawe.wer fdfpiaduf lksadurmq pe9981ek cagl9igdam.s .. diew r l;sie. 932 ..xouawpoe w.e;

She looked away from the screen and was momentarily staggered, soon relieved, as she realized her hot flush and racing heart were pointless. No one met her gaze, no one laughed at her work, everyone was utterly preoccupied with all things other than Cat McCabe, journaliste. Cat allowed herself a smile, looked at her screen and thought, well – it could be Finnish, deleted the lot and started to transcribe Hunter’s soundbites. Her typing speed matched the pace of his voice perfectly.

Now I’m going to sketch out a piece for the Guardian focusing on the non-European element of the Tour de France – mention Luca Jones and whether winning a Stage in the Giro D’Italia can translate to winning one at the Tour de France.

‘Hullo.’

I might do an ‘introducing Megapac’ – use my Hunter quotes, bring the riders of this wildcard team to the public’s notice.

‘Bonjour?’

In fact, it would be interesting to do a piece as an exposé of the cliques in the peloton according to nationality or language.

‘Buenos dias?’

There’s often inter-team friction, or factions, due to language – how does that change within the peloton at large?

‘Buon giorno? Guten Morgen? Hola!’

Cat looked up with a jolt.

‘Bonjour,’ she mumbled, wondering if she’d been talking her ideas out loud. She glanced at the man and was able to assess immediately that he appeared, physically at least, non-intimidating and relatively normal. For a start, he was wearing khaki shorts of decent dimensions and had a pen rather than a cigarette between his fingers.

The man flicked over a page of his notebook, squinted and then spoke.

‘Cat-riona McCabe?’ he asked. ‘Guardian?’

And he’s British.

‘Yes,’ Cat beamed, standing up and shaking his hand.

‘I’m Josh Piper,’ he said, extending his hand.

‘Oh – Josh-ua!’ Cat proclaimed, with a familiarity and joviality that made her cringe because they far exceeded the mere expression of recognition and relief she’d actually intended. ‘You’re English and you’re Joshua.’ She shook his hand anew.

‘Er, yes,’ he said, regarding her quizzically, ‘but please – it’s Josh and I’m relieved you’re Catriona McCabe – I’ve been standing here for ten hours saying hello in every language I know and some I probably don’t. You were miles away – where were you? Half-way up L’Alpe D’Huez already?’

Cat gave a guilty grin. ‘Not quite, but I was preoccupied. I’m sorry.’ To emphasize the point, she sat down again and stared concertedly at her screen.

Noticing that she still had her earpiece in place and that the dictaphone appeared still to be whirring and that her fingers were over the keys, Josh put his hands up in surrender.

‘You’re going to share the driving with us – right?’ His hands were now on his hips, as if it aided him in assessing her potential behind the wheel.

‘Yup, absolutely, thanks so much,’ Cat rushed.

‘This is your first Tour,’ he told her.

Am I that transparent?

Cat shrugged and nodded, trying to wipe the daft grin from her face.

But this is my first Tour – I’m here at the Tour de France – automatic smile drug.

‘It’s my seventh,’ Josh continued. ‘I read your Tour of Britain report for Cycling Weekly – I thought it was quite good.’

‘Thank you,’ Cat smiled, closing her eyes temporarily, revelling in such praise from a seasoned and respected journalist.

‘Good,’ Josh said. ‘How’s Taverner doing at the Guardian?’

‘My boss?’ Cat smiled on. ‘He’s fine – stressed out, as ever, but fine. Still racing a fair bit, winning not a lot but forever exhibiting his war wounds!’

‘I bet he was pissed off having to delegate this job out – it would have been his thirteenth tour.’

God, I have so far to go. So much to catch up on. Shoes to fill. A spectre to cast off. An impression to make.

‘Well,’ Josh continued, ‘nice to meet you. I’ll see you around.’

‘Thanks,’ said Cat, watching Josh blend with the press corps and suddenly kicking herself for not asking for his mobile number, or where they should meet on Sunday for Stage 1, or what she should do with her bags and what sort of car it was she was to help drive.

Why didn’t he invite me to sit by him? Or suggest coffee or sandwiches? Or ask where I’m staying?

Because you’re at work, not at a dinner party. Anyway, he was friendly and he did come to find you. Now write. Work.

I don’t know where to start. I’m still starving. Anyway, it’s the Saeco-Cannondale press conference in twenty minutes and I want to get a seat near the front so I can concentrate on Mario Cipollini.

Ten minutes later, as Cat was on her way out of the main ice rink to the press conference room, she came across Josh Piper headed in the same direction. It transpired they were staying at the same hotel.

‘Cipo, Cipo,’ Cat whispered as they took their seats and waited for the team. She turned to Josh and regarded him earnestly. ‘Mario Cipollini,’ she said, eyes asparkle. The sentence was complete, the profundity of its meaning and the depth of associated emotion were encapsulated in those two words.

‘I fucking love Cipo,’ said Josh, ‘I love him.’

‘So do I,’ Cat breathed, ‘I love Cipollini too.’

Josh shook her hand. ‘Can I call you Cat? We should meet for dinner this evening,’ said Josh, ‘there’s a few of us at the hotel.’

‘That would be lovely,’ said Cat earnestly, ‘and of course you can. Can I have your mobile number?’

Josh tipped his head. ‘Won’t it be easier if I just call your room from my room?’

‘Oh yes,’ said Cat, biting her lip and hoping that a grin might, in some way, counteract her inanity. Josh looked ahead and nudged her. She grinned at him again.

I have a friend!

She nudged him back. He turned to her, swiftly regarding her with a flicker of a frown, tipping his head towards the platform at the front, giving her a sharp nudge. Cat followed his gaze.

‘Cipo!’ Cat proclaimed involuntarily, her voice hoarse and regrettably loud. The two rows in front of her turned and stared. Mario Cipollini, however, nodded at her. Josh nudged her. She could feel him smile. Cat swelled.

Friday. Salle de presse. 10 a.m.

The press room wasn’t quite so unnerving, did not seem nearly as cavernous or quite so cacophonous the next morning, nor did the press corps seem as intimidating. Not least because there were now two faces known to her. Nevertheless, Cat set up her work space, settled herself down, opening a file and typing a few lines, before she scanned the mêlée and finally recognized the backs of Josh and also Alex Fletcher a few rows in front of her. She grinned at their shoulder blades, felt settled and keen to work.

I do hope Jimenez and Lipari weren’t twiddling their thumbs and at a loose end last night – because I was otherwise occupied. Josh did indeed call my room and we went out for a meal, with Alex Fletcher who is also travelling with us. Alex is very tall but his stature seems disproportionate to his demeanour – he’s like an excitable schoolboy – deplorable expletives every other word and a quite staggering lack of respect for his expense account. I had heard he can be brusque, that he requires an ego massage. But I like him, he’s amusing – it might even be fun with the three of us in the car.

‘Morning, Cat,’ said Alex, right on cue and towering above her, ‘fucking shit night’s sleep last night.’

Cat wasn’t quite sure how to respond, because she had slept very well, so she gave what she hoped was a sympathetic tip of her head. Alex loped off. Cat returned her attention to her still ominously blank screen.

I have to write my piece – Taverner wants 800 words on the Tour de France in general for Saturday’s issue as a prelude to the daily reports on each Stage.

‘Coming for coffee?’ said Josh. ‘Then the Zucca MV press conference?’

‘Sure,’ said Cat, quickly exiting her empty file as if it was full of secret scoops; grabbing her notepad and dictaphone, checking her back pocket for francs. ‘Bugger,’ she said, looking aghast, ‘I’ve come with no money.’

‘Money?’ Josh laughed. ‘You won’t need it – did you not eat during the day yesterday?’ Cat shook her head. ‘Well, Cat, Christmas comes early for the salle de presse – follow me.’

Josh took her out of the main ice rink and through to a much smaller hall where three sides of the room were lined with tables heaving under what appeared to Cat to be a veritable banquet.

‘No one loses weight on the Tour de France,’ said Josh, assessing Cat openly and deciding, in her case, that was a good thing.

‘Apart from the riders,’ said Cat.

‘Huh?’ said Josh, looking at his watch and then taking some baguette and brie.

‘The riders,’ Cat repeated, sitting down beside Josh and Alex, ‘they lose weight – they can lose around 4 pounds of muscle alone when the body starts to use it for energy.’

The baguette Josh was about to eat stopped midway to his mouth. Alex had a mouthful of coffee but put the gulp on hold.

‘How many calories a day do the riders consume?’ Josh asked, as if merely interested though Cat could tell she was being tested.

‘Between six and eight thousand,’ she shrugged, ‘60 per cent from complex carbs, 20 per cent from protein and 20 per cent from fat.’

‘Liquid?’ Alex demanded, having swallowed his.

‘Well, on a long Stage, and if it’s hot,’ Cat recited, ‘they need about 12 pints – but you see, the body can only absorb around 800 millilitres an hour, so fluid is always going to be a major concern. That’s why the drinks must be cold and hypertonic – they need to be absorbed quickly and to work efficiently.’

‘Also—’ Alex started but Cat hadn’t finished.

‘All riders fear thirst,’ she said gravely, taking a contemplative sip of Orangina, ‘because if you’re thirsty, it’s basically too late.’

‘Who rode the most Tours?’ Josh enquired, as if he had temporarily forgotten.

‘Joop Zoetemelk,’ Cat reminded him kindly, ‘sixteen in all.’ She regarded Alex, who was obviously musing over some taxing question. She saved him the trouble. ‘Maurice Garin,’ she said, ‘won the first Tour in 1903. Of course, the free wheel wasn’t invented until practically thirty years later,’ she added as an aside.

‘How many hairpin bends on L’Alpe D’Huez?’ Alex asked.

‘Twenty-one,’ replied Cat.

‘Fastest time trial?’ Josh pumped, raising an eyebrow at Alex over Cat’s split-second silence.

‘I reckon that would be Greg LeMond in 1989 – I think he averaged a fraction under 55 kph.’

‘Name the infamous Uzbekistan rider who won the green jersey and was—’

Cat interrupted Josh: ‘and was thrown off the 1997 Tour for testing positive?’

‘Him,’ Josh confirmed.

‘In fact,’ Alex mused, ‘spell him!’

Cat laughed. ‘I’ve named my two goldfish after him. Phonetically speaking, “jam-ollideen abdoo-jap-arov” have to be the most delicious words to roll off the tongue. Ever.’

‘Want a coffee?’ Alex asked, a certain reluctant admiration on his face. She nodded. He went off and brought back just the one, just for Cat. Josh took another chunk of baguette, laid two slithers of brie within it and proffered it to Cat. She accepted graciously.

Respect!

Friday. Zucca MV press conference. 12 p.m.

‘Come on, guys, or you’ll be late. Massimo – where’s Stefano? And where’s Vasily?’ Rachel McEwen was irritated; swinging the keys to the Fiat loaned to Zucca by the Tour de France, around and around her index finger. She had so much to do. Retrieving errant riders was not on her list.

Vasily Jawlensky, last year’s winner of the Tour de France, walked in a leisurely way across the car park. Rachel could never be cross with Vasily as he never intended to upset anyone.

‘Vasily,’ she said in a theatrical whimper, ‘where have you been?’

‘Viz my bike,’ Vasily replied as if Rachel really should have known the answer. Rachel smiled, nodded and laid a hand on his shoulder. She should have known. The majority of riders finish a race or a Stage, dismount and have no idea, or interest, in what happens to their bicycles. Most riders have little technical knowledge of their machines. But not Vasily. His first love, no doubt his dying love, is the bicycle.

Frequently, after his massage, he will venture to the car park of the hotel, to the team truck, and see to the wash-down and check-over of his bicycle himself. It helps him relax. He loves the company of the team mechanics. He is relaxed among them. When he looks back at the newspaper cuttings, the photos and film of his brilliant career, he does not look at himself, at the grimace of pain or the expression of elation he might be wearing, he does not look at the colour of the jersey on his back, or which rider is in front of him or, more likely, behind him. Unlike his team-mate Stefano Sassetta, Vasily would never consider analysing the dimensions of his thighs, the condition of his physique, the aesthetic merits of his categorically handsome face. Vasily Jawlensky’s attention in such instances is purely for the bike that is carrying him. He is the jockey, they are his transport to success.

To women, Cat most certainly amongst them, Vasily Jawlensky is a most gallant, enigmatic knight in shimmering lycra. For Vasily Jawlensky, his cycles are his magnificent steeds, his high-modulus carbon fibre and titanium chargers. He salutes them.

‘Just Stefano now,’ said Rachel, looking at her watch and then at Massimo and Vasily, who looked a little sheepish for having upset his soigneur whom he respected and liked. She unlocked the car and ushered the two riders in to the back.

‘You two,’ she said sternly, as if to a pair of dogs, ‘stay!’ They watched her sprint back into the hotel and, a few minutes later, pelt out again. She ran around to the side of the hotel where the team trucks were parked, disappearing from view just as Stefano appeared from the front of the hotel. He sauntered over to the team car and slipped into the front seat.

‘Ciao,’ he nodded to his team-mates.

‘Buon giorno,’ Massimo said.

‘How are you?’ said Vasily with great thought. The two riders communicated warmly but sparely in pigeon English.

Rachel reappeared, her hair loose and all over the place. She saw the laden car and walked briskly to it, settling herself in to the driver’s seat, studiously ignoring Stefano.

‘Ciao, Rachel,’ Stefano beamed, ‘where the fuck you been, hey?’ Rachel knew this scenario well. Accordingly, she switched on the ignition calmly and drove away. However, the frequent screech of brakes, the taking of liberties as she took corners, coupled with her loaded silence and wild hair told Stefano all he needed to know. He sat quietly and listened to Vasily and Massimo read all the signs they passed.

‘Bou-lang-er-ie.’

‘Mon-o-prix.’

‘Lin-ger-ie.’

Stefano tittered.

Rachel escorted her precious load to the conference room, swinging the car keys around her fingers. She smiled at Vasily. She smiled at Massimo. She even smiled at Stefano. When he took her hand to kiss, she stared at him very coldly, kept her hand to herself and marched away.

‘Where were you?’ Vasily asked Stefano as they took the stage in the conference room.

‘In the bar,’ Stefano shrugged, ‘coffee. With a nice girl.’

‘What are Vasily Jawlensky and Stefano Sassetta saying? Can you lipread?’ Cat urges Josh, who sits beside her. He shakes his head forlornly. ‘Can Alex?’ Cat implores, looking past Josh to the other journalist.

‘Only if the language is foul enough,’ Josh whispers, ‘or the topic suitably scandalous.’

Alex leans across them and giggles. ‘What a cunt!’ he exclaims; the fact that, being so tall has indeed brought his face about in line with Cat’s nether regions is momentarily alarming for the young journaliste who has known him for less than twenty-four hours. But Alex talks quickly and Cat, to her relief, discovers his foul fulmination is in fact peculiar praise for Stefano Sassetta. ‘He just said to Vasily that he was in a bar all night surrounded by women.’ Chinese whispers on this year’s Tour de France have begun.

Alex can speak Russian, Italian and French; his German is good, he can get by in Spanish and understands Portuguese. Zucca MV have no French riders and though they are predominantly an Italian team, the presence of their leader Vasily Jawlensky, last year’s yellow jersey, ensures that English is their chosen language when in any country other than Italy. Alex, however, giving Josh a nudge which, from its severity, is passed through his body and on to Cat, decides that familiarity will win him friends. And friends in the peloton will be an enviable commodity. So, in Russian, he asks Vasily probing questions about whether his new Pinarello bike for the Prologue Time Trial will reward him with the yellow jersey; then, in Italian, he asks Stefano Sassetta directly about his rivalry with Jesper Lomers.

Cat has been building up her nerve to ask Massimo’s opinions on the climbs of this year’s Tour but Alex’s bravado, his confident language-hopping, intimidates her and the confidence and acceptance she sensed from her facts-and-figures discourse over coffee evaporates. She is not consoled by the fact that Josh has just called Alex a show-off wanker, which, perversely, he has taken as a compliment. She wants to return to the salle de presse and make an inroad into her first article. Deadline is five hours away. She ought to start.

Stay put, Cat, the rest of the room is. Megapac are about to come in for their press conference.

Friday. Megapac press conference. 12.45 p.m.

Alex leans across Josh to Cat and racks his body into a brief silent laugh. Cat wonders which term for the female genitalia can possibly come out of his mouth next, most having done so already this morning. Alex surprises her.

‘Hey, Cat,’ he whispers, while the Megapac boys, a vision in burgundy and forest-green lycra, take their seats and tap their microphones and Josh regards Alex’s body sprawled again over his knees with exasperation, ‘what would you bid for Luca Jones?’ Alex winks suggestively. Cat regards him full on, glances at Luca and then back to Alex.

‘Why,’ she says with a very straight face, ‘everything I own and my soul to boot.’ This delights Alex. Cat and Josh share a flicker of a raised eyebrow and all three look at Luca, sandwiched between Hunter and Travis as if it is team strategy that some of their upright morals might just rub off on the young Lothario. Neither Josh nor Alex seem particularly interested in Megapac’s presence in the Tour de France but for Cat, there is a certain resonance for they, like her, are new to the show. On show. On trial. In France with dreams in their hearts and hope in their legs. Accordingly, fresh-faced earnestness replaces the showmanship exhibited by players in more established teams. Cat salutes Megapac.

The sight and sound of Hunter Dean, twice in twenty-four hours, lulls her into a false sense of familiarity and friendship.

He gave me a wink, remember.

Of course. Keep grinning and gazing at him as you are, you may even be awarded another.

Alex and Josh are comparing mobile phones like errant schoolboys might electronic pocket games during morning assembly. Somebody has asked the directeur sportif about sponsorship and the directeur is coming to the close of an informative but monotone soliloquy. For Cat, her surroundings have suddenly become dark, the sounds around her muffled. She feels detached and yet focused. She clears her throat, swallows once, carefully sets her pad and dictaphone to one side and then stands up.

‘Hunter?’

God, that was my voice. What the fuck was my question?

Cat’s voice seems to her too loud, too detached even to be her own. Its very femaleness has created a hush around her. Alex’s and Josh’s jaws have dropped.

‘Hi there,’ says Hunter, tipping his head and granting Cat his undivided attention. The other members of Megapac, racers and managers alike, are regarding her too. She daren’t look. She stares fixedly at Hunter.

Oh Jesus, Hunter Dean has just said hullo to me.

So, say hullo back.

‘Hullo. Um,’ Cat coughs a little, ‘what’s the strategy and is it personal or team?’

Hunter licks his lips and Cat, to her horror, realizes she has inadvertently licked hers in reply. ‘Huh?’ he responds.

‘Are you – singular – after a Stage win for yourself,’ Cat enunciates, involuntarily loudly, terrified she might fart or lose her voice with nerves, ‘or are you – plural – pursuing a complete team finish in Paris? Which is the greater glory?’

That sounded good! Very professional. Very salle de presse. Cat McCabe – journaliste.

‘Man,’ Hunter responds in his North Carolina drawl, ‘who says we can’t have both? The team’s strong – hey, y’all? I’m real strong. Mental confidence and physical strength feed each other, you know?’

Cat nods earnestly, hoping Josh has all this in shorthand or on tape. Luca leans forward to the mike, nods at Cat and then bestows upon her a dazzling smile that she is too stunned to reply likewise to.

‘You know,’ Luca says, keeping eye contact direct, ‘I would say each and every Megapac guy has a Stage win in his legs plus – plus – the desire for us to arrive together in Paris in his heart. We’re a team – you know?’

Now Hunter is nodding alongside Luca and Cat wonders if the three of them shouldn’t just quit the room and go and have a coffee somewhere. Which is pretty much what Luca is thinking, observing the pretty girl all serious and attentive – although he would of course drop Hunter from the equation.

‘The Tour de France,’ says Hunter, ‘is about team effort, team spirit, personal triumph plus – plus – pain. We’ll all be suffering, but hey, you’re not given a dream without the power to realize it!’

‘We are nine great riders racing under the Megapac flag,’ Luca proclaims in his gorgeous accent which today he sees fit to infuse with a twang of American. ‘You watch us go.’

‘I will!’ Cat enthuses. ‘Thank you.’

‘You’re welcome,’ says Hunter, who’s never been thanked in a press conference before.

‘It’s a pleasure,’ Luca smiles, thinking that a one-on-one interview with this girl would be a dictionary definition of pleasure.

‘You’re well in there,’ Alex growls under his breath, most impressed as Cat takes her seat, stares at her lap and wonders just how red her cheeks are. A healthy blush? Or downright crimson?

‘Good call,’ Josh says, reading through his notes and congratulating Cat genuinely, the facial colouring of his now-esteemed colleague being of little consequence to him.

I’m a bona fide journaliste, Cat thinks, trying not to let an ecstatic smile expose her as an adoring fan foremost.

‘I got propositioned by a total babe,’ Luca told Ben an hour later.

‘Oh Jesus!’ Ben exclaimed, dipping litmus paper into urine samples. ‘Are the groupies out in force already?’

‘Actually,’ Luca explained, ‘this one is a very welcome addition to the press corps – cor blimey!’ he added, tittering at his pun.

‘And she propositioned you?’ Ben laughed. ‘In the middle of a fucking press conference? Now, what did she say, I wonder? “Luca, Luca, after Stage 3, can we shag if you’re not too tired?” Something along those lines?’

Luca looked quite hurt. ‘Fuck you,’ seemed the most appropriate response, ‘she questioned me, man.’

‘And what did she ask?’ Ben asked with a wry smile giving a lively sparkle to his eyes. ‘Did she enquire as to the dimensions of your cog? How long you can keep going for?’

Luca did indeed hear the word as ‘cock’ and gave Ben a larky look which, predictably, said ‘fuck you’.

‘Well,’ he rued, ‘she actually asked about Personal Glory and Survival to Paris and shit – but she was a babe, let me tell you.’

‘I do believe you already have,’ said Ben. ‘Please ensure that for you, Personal Glory on the Tour de France is about racing your brilliant best. Keep your head down and direct all your energy – physical and mental – to la Grande Boucle.’

‘The big, beautiful, killer loop,’ Luca sighed, the route of this year’s Tour clearly mapped out in his mind’s eye. ‘Sure, Pop. Work first, then play – hey? That’s what I’m paid for.’

Ben cuffed Luca’s head and sent him on his way.

Friday. Team presentation. Hôtel de Ville, Delaunay Le Beau. 7 p.m.

Cat finished her piece. She polished the words and tweaked the punctuation until her brain felt frazzled. But the true headache befell her when she tried to e-mail it to the Guardian. In the phone room, the expletives in various languages from fellow journalists suffering similar telecom trauma were mildly comforting. She swore with the best of them for half an hour before technology kicked in and swiped her work away from her in a matter of seconds.

‘It’s the team presentation,’ she said to Josh and Alex, who were still in the throes of adjective selection.

‘It’s just the entire peloton in their gear but minus their bikes, poncing across the stage,’ Alex dismissed. Cat could think of nothing she’d like to see more.

‘It’s more for the VIPs and local dignitaries,’ Josh added, ‘like in horse-racing when the nags are paraded around before the off.’

‘Well,’ Cat said breezily, ‘this is my first Tour and I feel I ought to experience everything that’s going. So, à demain, mes enfants.’ She left the salle de presse and made her way to the town hall. It was humid, the still air hanging thick with the sense of anticipation felt by all connected with the race.

As thrilled as Cat was that she had made friends already, now, at the town hall, sneaking a seat near the front, she was most pleased that she was by herself. She wanted to soak up, savour and smile her way through the team presentation without being laughed at by Alex or, worse, perhaps to be judged and discredited by Josh.

I want to see my boys, standing before me, complete as teams, their bodies unharmed as yet by the traumas of the Tour. I want to keep the image – it’s important. Tomorrow changes everything.

Cat had come into close quarters with lycra-clad bike racers many times but it was bizarre, unsettling almost, to see the élite peloton so very out of context, paraded before her, for her, strutting their stuff without a bike in sight.

I almost don’t know where to look – because wherever I try to look, my eyes seem drawn back to the bulges. They’d give male ballet dancers a run for their money.

It was like a fashion show. Deutsche Telekom team, looking pretty impressive in pink, left the stage and Cofidis filed on, the riders’ chests and backs emblazoned with a vibrant golden sun symbol. Système Vipère looked stunning in their predominantly black lycra, a viper picked out in emerald and scarlet curling itself round each rider’s body and left thigh. Despite it being almost eight o’clock, Fabian Ducasse was wearing his Rudy Project sunglasses but Cat was perfectly happy that he should for he looked utterly stunning.

‘What do you miss?’ Cat understood the compère to be asking Fabian. Fabian replied with an expressive Gallic shrug-cum-pout and said wine and women. ‘What does Paris mean to you?’ the compère furthered. Fabian looked at him as if he was dense. ‘Wine and women, of course.’

And the yellow jersey, perhaps, thought Cat, not that Vasily will let it go easily, Oh, why can’t you both have it?

Zucca MV, in their blue and yellow strip, striped into rather dazzling and possibly tactical optically psychedelic swirls, sauntered on to the stage next and stood, legs apart, hands behind their backs. Though there was no music, Massimo Lipari was tapping his toe, nodding his head and grabbing his bottom lip with his teeth as if he were in a night-club and on the verge of dancing his heart out. Cat smiled. Stefano Sassetta smirked arrogantly, his torso erect, his thighs slightly further apart than those of his team-mates and, Cat noticed, tensed to show off their impressive musculature. Her eyes were on an involuntary bagatelle course; if they moved upwards from Stefano’s thighs, they hit his crotch from where they rebounded back to his thighs before being sent north again.

There’s padding and there’s padding – and I estimate that only a fraction of what Stefano has down there is padding. Blimey!

Zucca’s six domestiques, staring earnestly into the middle distance, same height, same build, same haircut, now the same peroxide blond, looked utterly interchangeable and Cat cussed herself for confusing Gianni with Pietro or Paolo and Marco and Mario or Franscesco.

They’re the cogs that keep Zucca’s wheels turning. If these boys weren’t domestiques, they’d most probably be working in their fathers’ restaurants. Not as head chefs or maître d’s, but as waiters, scurrying back and forth, keeping everybody happy. And they would indeed be happy – working for others is what they do. And they do it brilliantly and with pleasure. Their sense of family is strong. A family is a team. A team is a family. Put any obstacle in front of a line of soldier ants and they will not look for a way around it, they will climb up and over it and so it is with the Zucca MV domestiques. Their selflessness is legendary within the peloton. I’d like to write a piece about them.

Cat was making a mental note to phone the publishers of Maillot on Monday morning to propose such an article, when Megapac replaced Zucca MV on stage, the nine riders fresh-faced grinning virgins in comparison to the suave comportment of the Italian team who had a long-standing relationship with the Tour de France. She had to physically stop herself from leaping to her feet and waving at Hunter and Luca whom she now thought of as personal friends.

We meet again. You all look so lovely. Please take care. Have a good race. See you tomorrow. Adieu.

Catriona McCabe. Journaliste.

Cat McCabe is exhausted. She is back at the hotel, in her room, praying that neither Alex nor Josh will call for her. In fact, tonight she wouldn’t even open the door to Stefano Sassetta or Jose Maria Jimenez, no matter how insistently they knocked. The team presentation has been a reality check; she is truly here, on the eve of the Tour de France. She really is a journalist and a journaliste. She’s written her piece which Taverner rather liked, allowing her to keep the extra forty-four words which exceeded his word limit, and it will be published tomorrow morning.

Will He read it, I wonder?

He? Taverner? He has already – he liked it.

No – Him.

Why are you thinking about him, Cat? Aren’t your three weeks in France meant to be putting that all-important distance, in time and space, between you and all that?

I’m just wondering. I still miss Him, all right?

Who, Cat, or what? Do you miss the status of what he was – a long-term boyfriend – or do you miss the person he is? If it’s the former, that’s understandable; if it’s the latter, it’s unacceptable.

I know. It’s just the world seems a very spacious place without Him.

And your world was an unhappy one with him. Let him go. Let go. Here you are – just look where you are. You’re going to be fine.

Am I?

See her sitting up in bed. She is wearing a Tour de France T-shirt and a Team Saeco-Cannondale baseball cap. All the journalists are bribed with branded clothing and yet none are wearing them in public. Cat is disappointed. How can so many seem blasé when she herself is brimming with excitement? Cat has noted how it appears to be cool to wear branded items from previous Tours, but no one wears the current gifts as if somehow that would be too obsequious. Next year, though, no doubt they’ll be an enviable commodity and worn with pride and panache.

Cat, anyway, is wearing hers in bed, scanning L’Equipe and pleased that she can understand most of what she reads. She hauls her laptop from chair to bed and reads through her article. She pulls the neck of the T-shirt up and over her nose, inhaling deeply and knowing that, whenever she smells this T-shirt again, it will say to her ‘Tour de France, eve of the Prologue, Hôtel Splendide, Delaunay Le Beau. Room 50. Jimenez above, Lipari below. Alex Fletcher and Josh Piper in the bar. I was there.’ Cat pulls her cap down over her brow and reads.

COPY FOR P. TAVERNER @ GUARDIAN SPORTS DESK FROM CA TRIONA McCABE IN DELA UNA Y LE BEAU

The Tour de France is the most prestigious bike race in the world. It is also the most extravagantly staged event, not just in cycling but in sport in general.

La Grande Boucle does indeed trace a vast if misshapen 3,800 km loop across France. An entourage of 3,500 people, the Garde Républicaine motorcycle squad, 13,000 gendarmes, 1,500 vehicles and a fleet of helicopters escort the peloton whilst 15 million roadside spectators salute its progress as it snakes its way through France with speed, skill and tenacity in a gloriously garish rainbow splash of lycra.

The Tour de France is the race that every young European boy fantasizes about riding just as soon as the stabilizers are removed from his first bicycle. It is the race that is the inspiration for an amateur to turn professional, that every professional road-race cyclist desires to ride. It is the pursuit of a holy grail: to wear the yellow jersey, to win a Stage, to ride in a breakaway, or just to finish last in Paris albeit having lost three and a half hours to the yellow jersey over the three weeks.

Hell on two wheels, the Tour de France breaks bodies and spirits as much as it does records. It is also a beautiful and frequently moving event to watch, to witness. It is an adventure, a pilgrimage, a piece of history, of theatre, a soap opera unfolding against a stunning backdrop of France. For riders and spectators and organizers alike, it is a journey.

The Tour de France is a national institution raced by a multinational peloton, accompanied by an international entourage and broadcast to the world. It defines the calendar in France in much the same way as Bastille Day or Christmas. Similarly in Spain. And Italy. Belgium. Switzerland. Just not in Britain.

Ask any child anywhere European and hilly for their great idols and they will always name a cyclist. Ask any European sports star to name a hero, they will always hail a cyclist. Ask anyone, in fact, about their country’s key national figures, and they will invariably list a cyclist among them.

Why? Cyclists are heroes because of the bicycle itself; the ultimate working-class vehicle. Many cyclists come from modest beginnings and then achieve something great with their lives. Anyone can ride a bike. Anyone who rides a bike knows the effort it takes and will at some time experience pain – if it’s hot, cold, wet, hilly. The knowledge of that pain and that it is but a whisper of the pain and suffering which will be confronted and vanquished by a Tour de France rider, is why the peloton is considered to be made up of superhumans. They cross the Pyrenees and then head straight on to the Alps. Triumph over adversity. Man against mountain. May the play begin. Let the battle commence. May the best man win. Vive le Tour.

<ENDS>