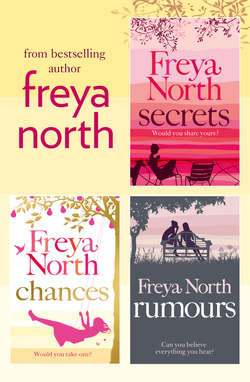

Читать книгу Freya North 3-Book Collection: Secrets, Chances, Rumours - Freya North - Страница 24

Chapter Twelve

ОглавлениеJoe did ring. The day after his departure, the evening of the day when Tess met Mary. Tess heard the phone and hovered, wanting it to be Joe but not wanting to take it for granted. When the answering machine clicked in and she heard his voice, for all the button-pushing configurations she tried, she could not interrupt it. She considered dialling 1471 in case he was phoning from a hotel or apartment, or she could call him back on his mobile – he'd left the number on the kitchen calendar. But she did neither because all his message actually said was that he was phoning, ‘like I said I would’. In the silence of the house after the answering machine clicked off, his message continued to reverberate in her mind. No ‘how are you’. No ‘hope all's well’. Joe's girl, indeed! Still, she found it impossible not to dither the evening away with whether to pick up the phone or not. She justified that she was too tired to speak anyway, what with all the cleaning and hills and Mary business.

While the TV flickered away in her peripheral vision, Mary accosted her mind's eyes. Tess realized she'd simply assumed Joe's parents were long dead because he spoke of both with an air of neutral finality. The more she thought about it, the more unnerving she found it that his mother lived in the same small town. Why hadn't he mentioned her before, let alone warned Tess of the probability that she'd come knocking? Ah, but was it any of her business – did it have anything to do with house-sitting? Well, yes, actually, it did – if someone was going to give her an almighty shock by lurking around the property and peering in through the windows, whatever their age or frailty. Didn't Joe usually warn his house-sitters about this? Or was it a more recent thing? Early-onset dementia. Mary was probably only in her mid-seventies. Was it still Mary's house – was Joe just house-sitting too?

Tess would be mentioning it to him when he next rang or returned. Your mum popped round for a cup of tea and a digestive. Nice place, that Swallows Residential Care Home, great view.

It was the view which Tess used as an excuse to push Em's buggy into the drive at Swallows at the end of the week. There'd been no further contact from Joe. No contact from anyone, actually, apart from the friendly but limited hellos, good mornings, and good afternoons of passers-by and the Everything Shop lady.

‘Would you look at that view,’ Tess marvelled to Em as they stood at the top of the driveway looking out over the downy clifftop and straight out to sea.

‘Can I help you? Visiting isn't for another ten minutes.’

‘Oh – I – we.’

The woman was in the same uniform that Laura had worn. Hers, it appeared, came without the smile. ‘That'll be quiet, will it? Some of them in there can get a little – excitable – if there's noise. Not that they're a quiet bunch themselves at the best of times.’

Tess looked at the woman and wondered where Laura was. She didn't like her daughter referred to as ‘that’ or ‘it’. Nor did she like the woman's implied exasperation when referring to the residents.

‘That is Emmeline,’ Tess said, ‘and Mrs Saunders is our friend.’

The woman folded her arms. ‘You're welcome to wait. But visiting's not for another ten minutes.’

‘Seven,’ Tess said as she pushed the buggy away.

The view was so lovely, the weather was good – but why were the benches in the garden empty? Why were the residents cooped up inside on a day like today? Was it staffing issues or strict scheduling? Then she asked herself what she was doing here anyway, taking it upon herself to visit this secret mother of Joe's. But she answered that it was a nice thing to do – for everyone concerned. And what else was she going to do with her day? She was tired of the scrubbing and the spiders and the hoicking; her body was stiff from stretching and ached from bending. And this was a change from walking to the pier, having only the fishermen and their empty nets to exchange nods with and sometimes a smile or a wave with Seb.

Returning to the front door a defiant seven minutes later, Tess was greeted by Laura.

‘I thought it sounded like you,’ she welcomed her warmly. ‘Don't mind Di – she's a crabby old slink. But she does have a heart. Somewhere.’

‘How's Mary?’

‘In one place today,’ Laura said, helping Tess up the steps with the buggy. ‘A little quiet, I'd say. How's this little 'un?’

Tess liked the way Laura squatted down regardless of the way it made her uniform stretch and strain.

‘How are you, Em?’

Em brandished her beaker in reply.

The place didn't smell of wee. It smelt more like a library, less like a hospital though it shared the linoleum floors and particular signage of the latter, and really only the hushed ambience of the former.

‘She's in the day room,’ Laura said over her shoulder as she led the way. She stopped at a door and peered through the safety glass. ‘As I said, you might find her a bit, well, distracted. Well, she was this morning.’ Laura looked at Tess. ‘But you can never tell, really, how long it's going to last. It goes as quickly as it comes – one minute they're away with the fairies, the next they're back in the land of the living. Sad when you think they'd rather not be.’

Tess looked into the room through the glass in the door and felt suddenly a little apprehensive. Was all this fair on Em? Or Mary? And even Joe too?

Laura sensed her reticence. ‘Come on, love, she'll be delighted with the company – whether or not she knows you from Adam today.’

The door opened into a world Tess knew existed but had never been party to. Her grandmother had died in hospital a day after being admitted from her own home. Here, though, were the infirm elderly en masse; all of them displaced because, for whatever reason, home was no longer an option. Yet there was a sense of calm about the place, perhaps because of the lack of movement: everyone was simply sitting, sitting as if waiting. Waiting for what? Three o'clock? But it was now five past. Visitors? There seemed to be only Tess and one other. The next meal? That wouldn't be for a while. Some looked as though they were barely breathing, jaws slack, eyes glassy and unfocused. As if they were simply waiting to – Tess didn't want to finish the thought so she smiled at everyone hoping to mask her pervasive feelings of sadness and, she had to admit, discomfort.

The light from the sun, from the expanse of North Sea and the huge sky, flooded the room spinning silver into grey hair and an opalescence to otherwise thin old skin. Even the minute lady whose wig had slipped had an air of composure about her – sitting serene, the light playing off the folds and creases of her baggy stockings like a Da Vinci drawing. Sitting beside her, a resident whose sandals revealed toes so overlapped Tess thought it made her look as if she'd been telling lies all her life. The lips of the lady with a startling blue rinse moved constantly, though whether she was talking to herself or just had an involuntary twitch Tess couldn't tell. But her eyes were fixed very darkly on the clock and Tess hoped it was for someone only five minutes late. Em toddled right ahead, looking intently at everyone as she went. Pair after pair of eyes that had been gazing listlessly at nothing in particular now had a welcome focus. One or two of the residents made a noise similar to beckoning a cat. A couple said a cheery hello. One gentleman, with no teeth, still broke into an expansive smile.

Someone said, little Daphne?

Mary, sitting in the corner, looking out to sea, said, Emmeline!

Em went to her outstretched hands. Tess following, nodding and saying hullo to all whom she passed. Mary was delighted, the crows’ feet around her eyes were like rays of sunshine suddenly radiating out from the interminable cloud of old age.

‘Little Emmeline! Where's Wolf?’

The child barked, to a round of applause. She and Mary knitted fingers for a while and communicated with nods and coos. As Tess sat beside them, it slowly dawned on her that she hadn't been noticed by Mary. And then it took for her to say, hullo, Mary! – Mary? Mrs Saunders? – to realize that actually Mary didn't recognize her at all. So Tess became a silent observer, proud to witness the pleasure Em was bringing to the room. Wherever Em went and whatever she picked up (and Tess noticed many similarities between an old-age-friendly room and a baby-friendly one) she received a chorus of approval. This community spoke in a language Em readily understood. They said, ‘apple’ when she picked one up. And when she pointed, they confirmed ‘book’ and ‘shoe’ and ‘blanky’ and ‘tick-tock’. And they nodded knowingly when she talked in gurgles and they clapped when she showed them something or pointed something out. But Mary just gave Tess a distracted, yes, dear when she tried to talk to her.

‘I could bring Wolf one day?’ she suggested to Laura. ‘I've heard of people doing that – taking dogs to care homes, hospices, prisons even. Petting lowers the blood pressure, it's been proven.’

‘It'll raise the blood pressure of Health and Safety,’ Laura declared. ‘A nice idea, love. Just you come back with Em. She's a little actress that one, isn't she. They've liked it – more successful than the flaming bingo I tried to organize last week.’

Tess looked at the lady with the blue rinse, with the ever-moving lips and the eyes fixed on the clock. She was the only resident on whom Em had had little impact. ‘That lady,’ she whispered to Laura. And then she didn't know what it was she wanted to know, it was none of her business after all.

‘Can't stop her doing it and believe me I've tried,’ Laura said anyway. ‘Whatever room she's in, if there's a clock, that's her – gone.’

‘Is she waiting for a visitor?’

‘Possibly,’ said Laura, ‘though she hasn't had one in all the time I've been here.’

An exhausted Em was asleep by the time her mother had strapped her into the buggy. Tess felt low. She'd suddenly felt desperate to leave Swallows, couldn't get out of there quick enough; she'd felt claustrophobic, unwell, but now in the fresh air she felt wretched. For the first time in weeks, she longed for someone to talk to. She wanted to say, Christ, let's go and have a coffee and a cake. She wanted someone with whom she could share the unexpected emotion of the visit. Will we too grow so old? Will you choose your hair to be blue? Will my toes knit like that? Will our chins get whiskery? Will we not mind if our teeth are in or out? Might that be us – waiting and waiting for no one to visit us? Will we sit and wait to die?

She pushed the buggy along the clifftop and stood awhile looking down the path leading to the cliff lift. There was no one around.

‘I'm lonely,’ she said quietly. ‘I'm really really lonely.’ She was immediately ashamed of the emotion.

She took Em home, cursing herself for destroying her SIM card, cursing SIM cards for damaging her memory for numbers in the way that a computer spell-check had compromised her ability to spell. She didn't even know Tamsin's number by rote. Then she wondered about her mobile handset itself. Did it have a memory of its own? She switched it on. And found that it did.

Tamsin didn't recognize Joe's landline number so she didn't take the call. Tess, though, rang again and again until she answered curtly out of frustration.

‘Tamz?’

‘Tess? Jesus freaking Christ, where the fuck are you?’

‘Hullo.’

‘You can't send me a text out of the blue saying you're fine and going away for a bit without telling me the whys and wheres, and then go completely off the radar for – what is it now – a month!’

‘Sorry.’

‘Where are you? I even went round to your flat and tried to break in. I thought – I don't want to tell you what I thought but it was grisly. Don't laugh. It wasn't bloody funny at the time.’

‘Tamsin – sorry. I didn't think.’

‘Where. The fuck. Are you?’

‘Saltburn.’

There was a pause. ‘Where. The fuck. Is Saltburn?’

‘In Yorkshire.’

‘In Yorkshire.’

‘Yes, in Yorkshire. On the north-east coast. It's gorgeous.’ Another pause. ‘I'm so glad you're enjoying your extended holiday.’

‘Tamsin, don't sound like that.’

‘Look, lady, people have been worried sick.’

Tess paused, racked her brains. ‘Who?’

‘Don't pull the “I don't have any friends” stuff on me. I've been worried. Geoff too. And I bumped into that girl you worked with – she said it was the gossip at the salon.’

‘But I told them.’

‘You didn't tell them why or where.’

‘I couldn't.’

They both paused. ‘When are you coming back? And where are you going to live when you do? I'm moving in with Geoff next month – otherwise, if I'd only known – And I saw your landlord, bizarrely, when I went round to find your corpse – he had a face like thunder saying you'd done a runner.’

‘I have.’

‘So I said he should calm down and there was probably an explanation and maybe there'd been a family crisis – what did you just say?’

‘A runner. I have done a runner, Tamsin. I've run away. I'm not coming back.’

Tamsin didn't dare pause. ‘I sort of want to hang up on you, but if I do I'll risk you never calling me again.’

‘Don't hang up, Tamz. Please don't. You have this number now.’

‘Don't hang up on me either – I just need to know if you're OK?’

‘I think so. I will be.’

‘Tess, were things really that bad? Why didn't you turn to me? I know Clapham is the other side of the world to Bounds Green – but Yorkshire's even further.’

Tess paused. ‘I had to go.’ Memories came back and she shuddered. ‘People made it seem that things were very bad for me.’

‘So you're hiding? How the hell can that help? You can't hurl your secrets out to sea and hope they'll disappear into the deep depths.’

‘Actually, I'm house-sitting, not hiding, and it can help. It already has. It's the most beautiful, beautiful place. And the man is called Joe – he builds bridges. And there's an old lady – Mary. I've just found out she's his mother. And there's a surfer called Seb. And a dog called Wolf. And a garden, the size of which you just can't imagine.’

‘It all sounds charmingly Mary Wesley, Tess.’

‘I had to leave, Tamsin. I know it's cowardly. But it was the only option. I was really starting to panic.’

‘I kept telling you to go to the Citizens Advice Bureau.’

‘I don't want advice. I know what they'll say. All I want is to bury the bad stuff. I just want a new start.’

‘Tess Tess Tess.’

‘I know,’ Tess said, ‘I know, I know.’

‘Don't you think you might be burying your head in the sand?’

‘I don't do beaches, Tamsin.’

‘You know what I mean.’

‘I don't think so. I'm not actually hurting anyone.’

‘But you – are you OK? And my goddaughter – is she OK too?’

‘We're both very OK. Em's really blossoming. It's just that today I felt a little – I don't know. Lonely. I don't want to cry –. Shit.’

‘Oh, Tess, come back – I'll help you work things out.’

‘You can't.’

‘Well, what can I do? Who knows you're there?’

‘Just you. And my sister.’

‘And I bet she's really interested.’

Tess considered this. And she realized that her sister hadn't even sounded surprised to hear from Tess, let alone to discover she had packed up her life and left London for a seaside town in the North. Tamsin's initial fury at Tess was different. It came from genuine concern. It came from love. And that helped. Tess didn't feel quite so lonely. She might not have Tamsin to hand, she might not see her for quite some time. But the fact that she was there for her, in spirit and now, at the end of the phone, was a comfort.

‘Please keep in touch, Tess? Regularly. Let me know you're OK.’

‘I will but I binned my mobile phone – it's snail-mail or landline only.’

‘How frightfully quaint,’ Tamsin murmured in a BBC accent.

‘Quaint is quite a good word for Saltburn, actually,’ Tess told her, ‘though it's gritty too, but that's what I like about it – it's real. I saw the most incredible sunset the other day. Then the next afternoon, I came across some young scamp glue-sniffing.’

‘You can see that down here,’ Tamsin said.

‘I know what you're saying. And I know why you're saying it. But there is something about this place – at this time – for me.’

‘OK, I hear you. Just stay in touch – please.’

‘I will. But I'd better go – the dog and child need feeding. Bye.’

‘You're loved!’ Tamsin interjected and with such urgency that Tess couldn't reply.

She stood looking at the replaced handset for a while, then wondered what to do about paying for the call. So she went and found one of the clean, empty jam jars she'd stored away and put a fifty-pence piece in it. Then she fed Em and Wolf, after which she bathed the former and turfed the latter out into the garden for his ablutions. She spent her evening designing a label for the jar, complete with a narrative of doodles and fancy lettering.

Telephone Tab.

Every now and then she'd say, oh shh! when the house creaked or the pipes groaned or a door squeaked open all by itself. But it didn't unnerve her. She quite liked it, now she'd grown used to it. The house – its sounds and smells and quirks – was now familiar. The place had such personality. It was as if the house had been a welcoming stranger at first, but Tess now felt she was living with a friend.

If she picks up the phone, I'll be phoning to say I'm coming back tomorrow. If she doesn't, bugger leaving another message – perhaps I'll squeeze in another weekend in London, see Rachel, head to Belgium on Monday. Or maybe I'll stay put, here in France. I don't know yet, until Tess answers.

Odd, though, that out of all the scenarios I'd probably forego rampant no-strings sex to spend time instead with her – to return to the North, to that faded old town, to that hulking old house and to that slightly odd single mum who is rearranging my home.

Tess could hear the phone ringing but she was not going to disrupt her luxuriating in such a decadently full bath. Whoever it was could leave a message. And if they didn't leave a message, then it wasn't her they wanted anyway.