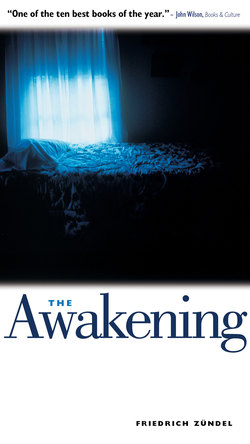

Читать книгу The Awakening - Friedrich Zuendel - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

I: THE FIGHT

ОглавлениеOn July 31, 1838, the people of Möttlingen, a small town in southern Germany, turned out to welcome their new pastor. A zealous thirty-three-year-old, Johann Christoph Blumhardt had spent years preparing for such a position, and was looking forward to serving his new flock as a minister, teacher, and counselor. Now, finally, he and his fiancée Doris Köllner could marry, settle down, and raise a family.

Blumhardt could never have anticipated the events he was about to be thrust into. Through them, the power of God to which he clung came close to him with a vividness experienced by only a few throughout history. At the request of his ecclesiastical superiors, he recounted these events in a detailed report entitled An Account of Gottliebin Dittus’ Illness. In his own memory the events lived on as “the fight.”

Before long, completely against Blumhardt’s wish, a distorted version of his report began to circulate publicly. This compelled Blumhardt, who had not even kept the original, to publish a carefully edited second version. He made one hundred copies and stated in the preface that he did not wish to see it circulated further.

Out of respect for that wish, the following account describes manifestations of supernatural forces only where necessary to demonstrate God’s victories over them. However, general, mysterious hints would envelop his struggle in an apocryphal twilight. Besides, Blumhardt regarded his experiences during the fight as so significant for the church and for the world that he would almost certainly agree to making their essential content public now. In a sense, we owe it to him to do so.

In the preface to his report Blumhardt wrote:

Until now I have never spoken with such boldness and candor to anybody about my experiences. Even my best friends look at me askance and act as though they feel threatened by even hearing about these things. Until now, most of it has remained a secret that I could have taken with me to the grave. It would have been easy to give an account that avoided offending any reader, but I could not do that. At almost every paragraph I asked myself if it was not rash to tell everything just as it was, but time and again an inner voice would say, “Out with it!”

So I dared it, in the name of Jesus, the victor. This is an honest report of what I can still remember, and I am firmly convinced that the Lord will hold his hand over me in this. My only intention is to tell everything to the honor of him who is the victor over all dark powers. I cannot take it amiss if somebody is mistrustful of these accounts, for these things are beyond our understanding. They are, however, based on observations and experiences over nearly two years, ones which can in every case be corroborated by eye-witnesses.

In speaking out unreservedly for the first time, I ask that the information given here be regarded as private, as when close friends share a secret. I also ask the reader to be so good as to read the whole report several times before forming a judgment. Meanwhile, I put my trust in Him who has human hearts in his power. Whatever the verdict of those who read this account, I rest assured in the knowledge that I have spoken the unvarnished truth, and in the rock-like certainty that Jesus is the victor.

Möttlingen, a parish at the northern end of the Black Forest which numbered 874 souls when Blumhardt arrived, encompasses two villages. Möttlingen proper, with a population of 535, overlooks the Nagold River and has the architecture, costumes, and customs of the Swabian lowland. Haugstett, the parish branch, is more typical of the Black Forest region, and its inhabitants were known at the time for a spirit of independence so fierce that it often bordered on hostility toward their pastor.

Near the edge of the village of Möttlingen stands a ramshackle house, recognizable now just as it was then by a window shutter bearing this weather-worn inscription:

Man, think on eternity,

And do not mock the time of grace,

For judgment is not far off.

In the spring of 1840 a poor family by the name of Dittus, consisting of two brothers and three sisters, moved into the ground floor apartment of this house. The eldest, Andreas, later became a village councilor. Then came Johann Georg, half blind and known as Hans. After him came three girls: Katharina, Anna Maria, and Gottliebin, who was born October 13, 1815. Their parents, both devout Christians, had died young.

Gottliebin was spiritually precocious and a favorite pupil of Pastor Barth, Blumhardt’s predecessor. Adept at composing verse, she later wrote many fine songs. Yet from childhood on she experienced uncanny things, and contracted one strange illness after the next, which more than once forced her to give up a good job. Though no one was certain of the cause of these afflictions, they were presumed to spring from her involvement in the magic practices rampant in rural German villages of the era. Barth used his connections to consult eminent physicians on her behalf, and she recovered fairly well from her last ailment, a kidney disease.

Gottliebin felt as attracted to Blumhardt as she felt repelled by him. At his first sermon she had to fight a desire to scratch his eyes out. On the other hand, Blumhardt could be sure of seeing her wherever she had a chance of hearing an uplifting word from him. For instance, she attended his service at the remote parish branch of Haugstett every week, even though one of her legs was shorter than the other, and it was difficult for her to walk long distances. She had a marked, dejected sort of shyness, which, when broken, revealed a defensive reserve. She made a downright unpleasant impression on Blumhardt and on others as well.

No sooner had the Dittuses moved into their new apartment than Gottliebin reported seeing and hearing strange things in the house. Other family members noticed them, too. On the first day, as Andreas said grace at table, Gottliebin fell unconscious to the floor at the words “Come, Lord Jesus, be our guest.” Then in the bedroom, sitting room, and kitchen her siblings heard recurring banging and shuffling, which terrified them and upset the people living upstairs.

Other peculiar things happened too. At night, for instance, Gottliebin would feel her hands forcibly placed one above the other. She had visions of figures, small lights, and other things and her behavior became gradually more repulsive and inexplicable. Yet because no one was greatly concerned about the “poor orphan family,” and because Gottliebin kept quiet about her experiences, most people ignored it. Blumhardt heard rumors about the matter, but he took no notice of them.

Finally, in the fall of 1841, when her nightly torments became unbearable, Gottliebin came to Blumhardt in his rectory. Voluntarily confessing various things from her past, she seemed to hope that confession would relieve her trials. Yet she spoke in such general terms that Blumhardt could not say much to help her.

From December 1841 through the following February Gottliebin suffered from erysipelas of the face and lay dangerously ill. Blumhardt did not visit her often however, as he was annoyed by her behavior. As soon as she caught sight of him, she would look to one side. When he greeted her, she would not reply. When he prayed, she would separate her previously folded hands. Though before and after his visits she acted fine, she paid no attention to his words and seemed almost unconscious when he was there. At the time, Blumhardt regarded her as self-willed and spiritually proud, and decided to stay away rather than expose himself to embarrassment.

Gottliebin did have a faithful friend and adviser in her physician, Dr. Späth and she poured out everything, including her spooky experiences, to him. Dr. Späth was unable to cure her strangest ailment – breast bleeding – but later, when Blumhardt took her into his care, it vanished, though he was informed of the complaint and its cure only later.

Not until April 1842, after the mysterious happenings had gone on for more than two years, did Blumhardt learn more details from the tormented woman’s relatives, who came to him for advice. They were desperate, for the banging noises that echoed through the house at night had become so loud they could be heard all over the neighborhood. Furthermore, Gottliebin had begun to receive visits from an apparition. The figure resembled a woman who had died two years before, and carried a dead child in her arms. Gottliebin claimed that this woman (whose name she only divulged later) always stood at a certain spot before her bed. At times the woman would move toward her and say repeatedly,“I just want to find rest,” or, “Give me a paper, and I won’t come again,” or something of the sort. As Blumhardt reported:

The Dittus family asked me if it would be all right to find out more by questioning the apparition. My advice was that Gottliebin should on no account enter into conversation with it; there was no knowing how much might be her self-deception. It was certain, I said, that people can be sucked into a bottomless quagmire when they become involved with spiritualism. Gottliebin should pray earnestly and trustingly; then the whole thing would peter out of its own accord.

As one of her sisters was away in domestic service and her brother wasn’t home much, I asked a woman friend of hers to sleep with her to help take her mind off these things if possible. But she was so disturbed by the banging that she helped Gottliebin investigate the matter. At length, guided by a glimmer of light, they discovered behind a board above the bedroom entrance half a sheet of paper with writing on it, so smeared with soot that it was undecipherable. Beside it they found three crowns – one of them minted in 1828 – and various bits of paper, also covered with soot.

From then on everything was quiet.“The spook business has come to an end,” Blumhardt wrote to Barth. Two weeks later, though, the thumping started again. By the light of a flicker of flame from the stove, the family found more such objects, as well as various powders. An analysis by the district physician and an apothecary in nearby Calw proved inconclusive.

Meanwhile, the banging increased; it went on day and night and reached a peak whenever Gottliebin was in the room. Along with some others who were curious, Dr. Späth twice stayed in the apartment overnight, and found it worse than he had expected. The affair became more and more of a sensation, affecting the surrounding countryside and drawing tourists from farther away. In an attempt to put an end to the scandal, Blumhardt decided to undertake a thorough investigation himself. With the mayor Kraushaar (a carpet manufacturer known for his level-headedness) and a half dozen village councilors, Blumhardt made secret arrangements for an inspection during the night of June 9, 1842. In advance he sent Mose Stanger, a young married man related to Gottliebin who later became Blumhardt’s most faithful supporter. The others followed at about ten o’clock in the evening, posting themselves in pairs in and around the house.

As Blumhardt entered the house, he was met by two powerful bangs from the bedroom, followed by several more. He heard all sorts of bangs and knocks, mostly in the bedroom, where Gottliebin lay fully clothed on the bed. The other observers outside and on the floor above heard it all. After a while they all gathered in the ground floor apartment, convinced that what they heard must originate there. The tumult seemed to grow, especially when Blumhardt suggested a verse from a hymn and spoke a few words of prayer. Within three hours they heard the sound of twenty-five blows, directed at a certain spot in the bedroom. These were powerful enough to cause a chair to jump, the windows to clatter, and sand to trickle from the ceiling. People living at a distance were reminded of New Year’s Eve firecrackers. At the same time there were other noises of varying volume, like a light drumming of fingertips or a more or less regular tapping. The sounds seemed to come mainly from beneath the bed, though a search revealed nothing. They did notice, though, that the bangs in the bedroom were loudest when everybody was in the sitting room. Blumhardt reported:

Finally, at about one o’clock, while we were all in the living room, Gottliebin called me to her and said she could hear the shuffling sound of an approaching apparition. Then she asked me if, once she saw it, I would permit her to identify it. I refused. By that time I had heard more than enough and did not want to run the risk of having many people see things that could not be explained. I declared the investigation over, asked Gottliebin to get up, saw to it that she found accommodation in another house, and left. Gottliebin’s brother Hans told us later that he still saw and heard various things after our departure.

The next day, a Friday, there was a church service. Afterward, Gottliebin went to visit her old home. Half an hour later a large crowd had gathered in front of the house, and a messenger notified Blumhardt that Gottliebin was unconscious and close to death. He hurried there and found her lying on the bed, completely rigid, her head burning hot and her arms trembling. She seemed to be suffocating. The room was crammed with people, including a doctor from a neighboring village who happened to be in Möttlingen and had rushed to the spot. He tried various things to revive Gottliebin but went away shaking his head. Half an hour later she came to. She confided to Blumhardt that she had again seen the figure of the woman with the dead child and had fallen to the floor unconscious.

Another search of the place that afternoon turned up a number of strange objects apparently connected with sorcery – including tiny bones. Blumhardt, accompanied by the mayor, took them to a specialist, who identified them as bird bones.

Wishing to quell the general hubbub, which was now getting out of hand, Blumhardt found new accommodations for Gottliebin, first with a female cousin and later with another cousin, Johann Georg Stanger (the father of Mose Stanger), who was a village councilor and Gottliebin’s godfather. Blumhardt advised Gottliebin not to enter her own house for the time being, and she agreed – in fact, she did not move back there until the following year. He also tried to prevent further commotion by advising her brother Hans not to visit her.

I had a particular dread of manifestations of clairvoyance, which are often unpleasantly sensational. A mysterious and dangerous field had opened up before me, and I could only commit the matter to the Lord in my personal prayers, asking him to protect me in every situation that might arise. Whenever the matter took a more serious turn, the mayor, Mose, and I would meet in my study to pray and talk, which kept us all in a sober frame of mind.

I shall never forget the fervent prayers for wisdom, strength, and help that those men sent up to God. Together we searched through the Bible, determined not to go any further than Scripture led us. It never entered our minds to perform miracles, but it grieved us deeply to realize how much power the devil still has over humankind. Our heartfelt compassion went out not only to the poor woman whose misery we saw before us, but to the millions who have turned away from God and become entangled in the secret snares of darkness. We cried to God, asking that at least in this case he would give us the victory and trample Satan underfoot.

I t took weeks for the uproar in the area to die down. Complete strangers came and wanted to visit the house, some even wanting to spend a night in it to convince themselves that the rumors were true. But Blumhardt resolutely refused all such requests, including one made by three Catholic priests from nearby Baden, who wanted to spend several hours in the house at night. The house was placed under the watchful custody of the village policeman, who happened to live opposite it.

Gradually things quieted down, and most people in the village remained unaware of what followed, though occasionally this or that came to somebody’s notice. As for his own congregation, Blumhardt later said, “Generally speaking, I met with earnest, reverent, and expectant sympathy throughout the fight, even if it was mostly unspoken. That made it much easier for me to hold out, while at the same time rendering it impossible for me to give up.” Meanwhile the din in the house continued unabated and only ended a full two years later.

Before long, similar noises started in Gottliebin’s new dwelling. Whenever they were heard, she would fall into violent convulsions that could last four or five hours. Once they were so violent that the bedstead was forced out of joint. Dr. Späth, who was present, said in tears, “The way this woman is left lying here, one would think there is no one in this village to care for souls in need!”

Blumhardt took up the challenge and began visiting Gottliebin more often:

Her whole body shook; every muscle of her head and arms burned and trembled, or rattled, for they were individually rigid and stiff, and she foamed at the mouth. She had been lying in this state for several hours, and the doctor, who had never seen anything like it, was at his wits’ end. Then suddenly she came to, sat up, and asked for a drink of water. One could scarcely believe it was the same person.

One day a traveling preacher acquainted with Gottliebin visited her and dropped in at the rectory. On taking leave, he raised a forefinger at Blumhardt and admonished him, “Do not forget your pastoral duty!”

“What am I to do?” thought Blumhardt. “I’m doing what any pastor does. What more can I do?”

Some time later, on a Sunday evening, Blumhardt visited the sick woman again. Several of her friends were present. Sitting some distance from her bed, he silently watched as she convulsed: twisting her arms, arcing her back in the most painful manner, and foaming at the mouth. Blumhardt continued:

It became clear to me that something demonic was at work here, and I was pained that no remedy had been found for the horrible affair. As I pondered this, indignation seized me – I believe it was an inspiration from above. I walked purposefully over to Gottliebin and grasped her cramped hands. Then, trying to hold them together as best as possible (she was unconscious), I shouted into her ear, “Gottliebin, put your hands together and pray, ‘Lord Jesus, help me!’ We have seen enough of what the devil can do; now let us see what the Lord Jesus can do!” Moments later the convulsions ceased, and to the astonishment of those present, she woke up and repeated those words of prayer after me.

This was the decisive moment, and it thrust me into the fight with irresistible force. I had acted on an impulse; it had never occurred to me what to do until then. But the impression that single impulse left on me stayed with me so clearly that later it was often my only reassurance, convincing me that what I had undertaken was not of my own choice or presumption. Of course at the time I could not possibly have imagined the horrible developments still to come.

Blumhardt only recognized the full significance of this turning point later on. He had turned deliberately and directly to God, and God had immediately begun to guide his actions. From this point on, Blumhardt was convinced that it was vital for the ultimate victory of God’s kingdom that the kingdom of darkness and its influences suffer defeat here on earth. He also recognized more clearly the role of faith in the struggle between light and darkness. The depth to which divine redemption penetrates into human lives in this struggle, he saw, ultimately depends on the faith and expectation of its fighters.

Blumhardt explained what he saw as his own role in all this:

At that time Jesus stood at the door and knocked, and I opened it to him. This is the call of Him who wants to come again: “Behold, I stand at the door; I am already waiting there. I want to come into your life, want to break into your ‘reality’ with the full power of grace given me by the Father, to prepare for my full return. I am knocking, but you are so engrossed in your possessions, your political quarrels, and theological wrangling, that you do not hear my voice.”

Far from fully subsiding after Blumhardt’s intervention, Gottliebin’s illness soon resumed in earnest. Following this first breakthrough, the woman had several hours of peace, but at ten o’clock in the evening Blumhardt was called to her bedside again. Her convulsions had returned. Blumhardt asked her to pray aloud, “Lord Jesus, help me!” Once more, the convulsions ceased immediately, and when new attacks came Blumhardt frustrated them with the same prayer, until after three hours she was able to relax and exclaimed, “Now I feel quite well.”

Gottliebin remained peaceful until nine o’clock the following evening, when Blumhardt called on her with two friends he brought along whenever he knew her to be alone. As they entered Gottliebin’s room, she rushed at Blumhardt and tried to strike him, though she seemed unable to aim the blows effectively. After this, she plunked her hands down on the bed, and it seemed to those present as if some evil power came streaming out through her fingertips. It continued like this for some time, until finally the convulsions abated.

But before long, a new wave of distress engulfed Gottliebin. The sound of tapping fingers was once more around her, she received a sudden blow on her chest, and she once more caught sight of the apparition she had seen in her old home. This time she told Blumhardt who the figure was; it was a widow who had died two years before, a woman Blumhardt knew well. In her last days she had sighed a lot, and said she longed for peace but never found it. Once, when Blumhardt had quoted to her from a hymn, “Peace, the highest good of all,” she had asked him for it and copied it. Later, on her deathbed, tormented by her conscience, she had confessed several heavy sins to Blumhardt, but it had not seemed to give her much peace. Blumhardt wrote:

When I got to Gottliebin, I heard the tapping. She lay quietly in bed. Suddenly it seemed as if something entered into her, and her whole body started to move. I said a few words of prayer and mentioned the name of Jesus. Immediately she began to roll her eyes, pulled her hands apart, and cried out in a voice not her own, either in accent or inflection, “I cannot bear that name!” We all shuddered. I had never yet heard anything like it, and in my heart I called on God to give me wisdom and prudence –and above all to preserve me from untimely curiosity. In the end, firmly resolved to limit myself to what was necessary and to let my intuition tell me if I went too far, I posed a few questions, addressing them to the voice, which I assumed belonged to the dead widow. The conversation went something like this:

“Is there no peace in the grave?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“It is the reward for my deeds.”

“Have you not confessed everything?”

“No, I murdered two children and buried them in a field.”

“Do you not know where to get help? Can you not pray?”

“I cannot pray.”

“Do you not know Jesus who can forgive sins?”

“I cannot bear the sound of that name.”

“Are you alone?”

“No.”

“Who is with you?”

Hesitatingly, but then with a rush, the voice replied, “The most wicked of all.”

The conversation went on like this for a while. The speaker accused herself of sorcery, on account of which she was bound to the devil. Seven times she had possessed someone and then left his or her body, she said. I asked her if I might pray for her, and after some hesitation she permitted me. When I finished, I told her she could not remain in Gottliebin’s body. At first she seemed to plead with me, but then she became defiant. However, I commanded her to come out. At that, Gottliebin’s hands fell forcefully to the bed, and her possession seemed to come to an end.

Along with his close friends the mayor and Mose Stanger, Blumhardt earnestly pondered whether or not he should enter into even a limited conversation with a spirit. The Bible always guided them in such considerations, particularly the passage starting at Luke 8:27. In light of his own experiences, Blumhardt offered the following thoughts on Luke’s account of how Jesus healed the possessed Gergesene:

Luke reports that instead of departing immediately, as was usually the case, the demons voiced a request. They feared being sent into the abyss. Evidently, Jesus did not respond harshly. Having come to redeem the living and the dead to the widest extent possible, he, their future judge, could not stand there insensitive. Hence he showed himself approachable, and stopped to listen. He asked the unclean spirit, who was representing all the others, “What is your name?” He evidently put this question not to the possessed man, but to the spirit speaking out of him; he wanted to know what name the spirit had when alive.

Jesus was aware that demons, as departed human spirits, fear hell. By asking the demon’s name– which he, being the Lord, would of course already know – he showed interest and compassion. This also suggests that he considered the demon to be human rather than non-human. The demon chose not to reveal his name, thus cutting himself off from further consideration the Lord would have been glad to show him, to let those present see how all-embracing his redemptive urge was. Instead, the spirit replied, “Legion, for there are many of us.” This answer indicates that there were many in need of freeing.

States of possession like this give one a glimpse of something mysterious, incomprehensible, indeed horrifying: thousands of spirits looking for shelter in a human being or in subjection to a dark power that compels them to torment the living.

T o return to our story, Gottliebin experienced another apparent instance of possession a few days later, though this time Blumhardt did not intervene as he had before. It seemed as if specific demons were now coming out of her by the hundreds. Every time it happened, the woman’s face assumed a new, threatening mien. The demons, by their own admission, were not permitted to touch Blumhardt, but they did attack the others present, including the mayor, who received more than a few blows. Gottliebin meanwhile yanked her hair, beat her breasts, banged her head against the wall, and tried to injure herself in other ways, though a few simple words from Blumhardt seemed to calm her.

As these scenes grew increasingly terrible, Blumhardt’s presence sometimes seemed to make matters worse. He related:

No words can describe what I endured in soul and spirit at that time. I so badly wanted to have done with the matter. True, in each instance I could depart with inward satisfaction, believing that the demonic power had given way and that the tormented woman was again completely all right. However, the dark powers always seemed to gain fresh strength, so intent were they on entangling me in a labyrinth and ruining me.

All my friends advised me to give up. But I thought with horror of what might become of Gottliebin if I withdrew my support, and how everyone would consider it my fault if things turned out badly. I would endanger myself and others if I tried to extricate myself by withdrawing. I felt caught in a net. I must also admit that I felt ashamed to give in to the devil– in my own heart and before my Savior, whose active help I had experienced so many times. I often had to ask myself, “Who is Lord?” And I always heard an inner voice call: “Forward! We may first have to descend into the deepest depths, but it must come to a good end, if it is true that Jesus crushed the Serpent’s head.”

As the scenes in which demons came out of Gottliebin grew more frequent, there were other mysterious occurrences as well. For example, one night when she was asleep, Gottliebin felt a scorching hand grab her throat, leaving large burns behind. Her aunt, who slept in the same room, lit a lamp, and found blisters around Gottliebin’s neck. Day and night Gottliebin would receive unexplainable blows to her head or side. On top of this invisible objects tripped her in the street or on the stairs, causing sudden falls and resulting in bruises and other injuries.

On June 25, 1842, Blumhardt was informed that Gottliebin had gone mad. When he called on her the following morning, everything seemed to be well. However, in the afternoon Gottliebin suffered such a violent attack that it left her as if dead. Once again it appeared that demons were coming out of her, with a force that exceeded anything Blumhardt had experienced previously. To him, it felt like a victory of incomprehensible magnitude. For the next several weeks nothing much happened, and Gottliebin walked the village unmolested and unharmed.“It was a time of rejoicing for me,” Blumhardt later said.

He had earned that joy. Even his best friends had warned him not to get involved in the conflict. But Blumhardt had acted boldly, staking everything on his assurance that Jesus Christ is the same today as he was two thousand years ago, when for the sake of suffering humankind, he had stopped the powers of darkness in their tracks. He had remained at his post like a soldier, neither advancing rashly nor retreating, and had held the field.

When the fight was at its fiercest, on July 9, 1842, he wrote to his predecessor and mentor Barth, “Whenever I write the name of Jesus, I am overcome by a holy awe and by a joyous, fervent sense of gratitude that he is mine. Only now have I truly come to know what we have in him.”

But if anyone thought the fight was now over, they were wrong. As Blumhardt put it, he seemed to have taken on an enemy who constantly brought out fresh troops.

In August 1842 Gottliebin came to him, pale and disfigured, to tell him something she had been too shy to reveal but could keep hidden no longer. At first she hedged, making him tense and apprehensive, but finally came out and told him how every Wednesday and Friday she would bleed so painfully and severely that she was sure she was dying. In her description of other things she experienced in connection with this bleeding, Blumhardt recognized several bizarre fantasies of popular superstition, apparently become reality. He later recalled:

To begin with, I needed time to collect my thoughts, as I realized what a hold the power of darkness had gained over humanity. My next thought was “Now you are done for; now you are getting into magic and witchcraft, and what can you do to protect yourself against them?” But as I looked at her in her distress, I shuddered to think that such darkness could be possible, and help impossible. I recalled that there are people thought to have secret powers enabling them to ward off all manner of demonic evils; I thought of the sympathetic magic that people swear by. Should I look around for something of that sort? But I couldn’t. I had already long felt that that would be using devils to drive out devils. At one point, it is true, I considered affixing the name of Jesus to the door of a sick person’s house, but then I found a warning in Galatians 3:3: “Can it be that you are so stupid? You started with the spiritual; do you now look to the material?” I took this as a reminder to keep to the pure weapons of prayer and God’s word.

Questions flooded through me: Cannot the prayers of the faithful prevail against this satanic power, whatever it be? What are we poor people to do if we cannot call down direct help from above? Because Satan has a hand in it, must we leave it at that? Can he not be defeated through faith? If Jesus came to destroy the works of the devil, ought we not to hold on to that? If magic and witchcraft are at work, is it not a sin to let them continue unchecked when they could be confronted?

With these thoughts I struggled through to faith in the power of prayer, where no other counsel was to be had. I said to Gottliebin, “We are going to pray; come what may, we shall dare it! There is nothing to lose. Almost every page of Scripture tells of prayer being heard. God will keep his promises.” I let her go with the assurance that I would pray for her and asked her to keep me informed.

The next day, a Friday, was unforgettable. Toward evening – as the first storm clouds in months began to gather across the sky – Gottliebin was thrown into a veritable frenzy. First she raced madly from room to room looking for a knife so she could kill herself. Then, running up to the attic, she sprang onto a windowsill. While standing on the ledge, ready to jump, the first lightning of the approaching storm startled her and brought her to her senses. “For God’s sake, I don’t want that!” she cried. But her sanity lasted only a moment. Once more delirious, she took a rope – later she was not able to say how it had come into her hands – wound it artfully around a beam in the loft, and made a slip knot. Just as she pushed her head through the noose, a second flash of lightning caught her eye and brought her around as before. The next morning when she saw the noose on the beam, she wept, claiming that in a sober state of mind she never could have tied such a clever knot.

At eight o’clock the same evening, Blumhardt was called to Gottliebin and found her in a pool of blood. He said a few comforting words to her, but she did not respond. Then, as thunder rolled outside, he began to pray earnestly.

As I prayed, the anger of the demons afflicting Gottliebin broke loose with full force, howling and lamenting, “Now the game is up. Everything has been betrayed. You have ruined us completely. The whole pack is falling apart. It is all over. There is nothing but confusion, and it is all your fault. With your unceasing praying you will drive us out completely. Alas, alas, everything is lost! We are 1,067, but there are many others still alive, and they ought to be warned! Oh, woe to them, they are lost! God forsworn– forever forlorn!”

The howls of the demons, the flashes of lightning, the rolling thunder, the splashing of the downpour, the earnestness of all present, and my prayers, which seemed to literally draw the demons out– all this created a scene that is very difficult to imagine. Among other things, the demons yelled, “Nobody could have driven us out! Only you have managed it, you with your persistent praying.”

After fifteen minutes of intercession, Gottliebin came to and Blumhardt and the others left the room while she changed her clothes. As he tells it, “When we came back and found her sitting on her bed, she was a completely different person. There was no room in us for anything but praise and thanks. The bleeding had ended for good.”

Before long other demonic manifestations made their appearance. Blumhardt, unable to see the way forward, poured out his need to a friend, the director of a seminary, who pointed him to Jesus’ words, “There is no means of casting out this sort but by prayer and fasting” (Matt. 17:21). Thinking on it further, Blumhardt began to wonder whether fasting might not be more meaningful than he had previously assumed:

Insofar as fasting enhances the intensity of prayer and shows God the urgency of the person praying (in fact, it represents a continuous prayer without words), I believed it could prove effective, particularly since this was specific divine advice for the case at hand. I tried it, without telling anybody, and found it a tremendous help during the fight. It enabled me to be much calmer, firmer, and clearer in my speech. I no longer needed to be present for long stretches; I sensed that I could make my influence felt without even being there. And when I did come, I often noticed results within a few moments.

A few other accounts of demonic manifestations are worth mentioning here too. Blumhardt tells, for example, of apparent differences among the demons. Some were defiant and full of hatred toward him, crying, among other things, “You are our worst enemy, and we are your enemies. Oh, if only we could do what we want!” Some expressed a horror of the abyss, which they perceived to be very near, and uttered things such as, “Would that there were no God in heaven!” And yet they assumed full responsibility for their own downfall. One particularly dreadful demon, whom Gottliebin had seen earlier in her house and who now admitted to being a perjurer, repeatedly exclaimed the words painted on the window shutter of that house:

Man, think on eternity,

And do not mock the time of grace,

For judgment is not far off.

Then he would fall silent, contort his face, stiffly raise three of the sick woman’s fingers, and then shudder and groan. There were many bizarre scenes of this kind, and Blumhardt would gladly have welcomed more witnesses to corroborate his reports of them.