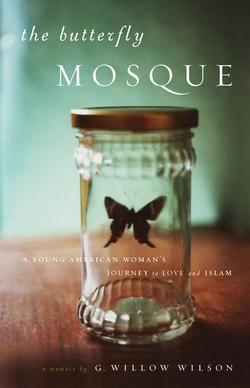

Читать книгу The Butterfly Mosque - G. Willow Wilson - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Prologue

ОглавлениеIN THE UPPER REACHES OF THE ZAGROS MOUNTAINS, THE AIR changed. The high altitude opened it, cleared it of the dust of the valleys, and made it sing a little in the lungs; low atmospheric pressure. It was a shift I recognized. We had been driving for hours, winding north along a wide dry basin between high peaks; then we turned west. Now the car, an old Peugot, struggled upward along switchbacks cut into the mountainside, past intersecting layers of rock laid down over geological ages.

For a moment I was reminded intensely of home. It had been almost a year since I had been back to Boulder, in the foothills of the Colorado Rockies. The snug valley where I had gone to high school, learned to drive, where my parents and sister still lived, could be seen as a tidy whole from this height in cliffs much like these. Looking down into the plain below, I felt as though I was seeing double, and that an hour’s hike along the switchbacks would bring me to my own doorstep.

At the time, it was a sensation that seemed a little perverse. I had just flown into Iran from Egypt—this journey had begun thousands of miles from my own country. That a mountain and a change in the air in Iran should make me think of home in the spring of 2004, the spring of the War on Terror, the clash of civilizations, the jihad, the things that had made my quiet life almost unlivable, must be sheer perversity, I thought then. I didn’t yet realize that the Zagros Mountains had no name when they were forced out of the ground millions of years ago, and neither did the Rockies, that the call of earth to earth might be something more real than the human divisions of Iran and America. I had faith, then; it was in the mountains that I first thought of divinity, and these mountains reminded me of that sensation. But I didn’t yet have faith in faith—I didn’t trust the connections I felt between mountains or memories, and if I had been a little more ambivalent, I could have allowed the Zagros to be foreign, and the memory to be coincidence.

Fortunately, I didn’t.

Ahmad, my guide plus chaperone, pointed west over the receding peaks.

“If you kept driving that way, you would get to Iraq,” he said. He was from Shiraz, and had silver hair and laugh lines. Before the revolution he flew planes for the Shah, whom he had hated, but not as much as he now hated the mullahs. During one of our conversations on the road from Shiraz to Isfahan, he told me he used to fast during Ramadan and pray with some regularity. In his eyes, though, the Islamic regime had so deformed his religion that he stopped. Thinking I would judge him for this lapse lest he provide a rationale (I was an American and a Sunni, and therefore unpredictable) he told me he didn’t need to fast; fasting was meant to remind one of the hunger of the poor, and he helped the poor in other ways.

“Then why do the poor fast?” I asked him. The Ramadan fast was required of all Muslims, not just the wealthy. He looked at me out of the corner of his eye; evidently I was an American Sunni who discussed theology. Among the middle classes, theology had gone out of fashion in Iran. But I had just come from Egypt, where the reverse was true. Ahmad left the question floating in the air.

“Iraq?” I climbed on a rock near the edge of the promontory where we were standing, having parked the car on the shoulder of the road. My Nikes stuck out from under the hem of my black robe. I had overdressed. In Khatami’s Tehran, chadors and manteaux had been replaced by short, tight housecoats and scarves that were barely larger than handkerchiefs. Knowing only that Iran was under a religious dictatorship, and Egypt was under a military one, I had dressed as conservatively as possible. I didn’t realize that whatever the political reality, Egypt was far more socially conservative than Iran. The reasons for this would become clear to me only later: when a dictatorship claims absolute authority over an idea—in the case of Iran, Islam, in the case of Egypt, a ham-fisted brand of socialism—frustrated citizens will run to the opposite ideological extreme. The Islamic Republic was secularizing Iran; in Egypt the short-robed fundamentalists multiplied and multiplied.

“Yes, Iraq. I think at night farther southwest you could maybe see the bombs falling. But far away; first the plain of Karbala, then Baghdad.” Ahmad came to stand next to my rock, and pointed northwest. “Karbala is where Imam Husayn is buried.”

“We have his head,” I said, thinking of the fasting argument. “In Cairo. There’s a square named after him where the shrine is.”

“What?”

“His head,” I repeated, wondering whether I should put an honorific before his; Husayn ibn Ali was a grandson of the Prophet and beloved by all Muslims, but particularly revered by Shi’ites. I didn’t want to commit a faux pas. No matter what Ahmad thought about fasting. I put one hand to my back; the infection in my kidneys had manifested itself as a dull spreading pain there, and a touch of fever. Living in an industrial neighborhood in Cairo, not a clean city to begin with, I had developed an unfortunate apathy toward my health.

“This is the first time I hear this about Imam Husayn,” muttered Ahmad, and broke out into a laugh.

“It’s true,” I said. “The Fatimids brought him with them. At least, that’s what the ulema tell us; maybe it’s all a lie and the shrine is empty.” A light wind ran down the channel of the valley below. I took a breath and held it for a moment, then let it out in a sigh. Ahmad smiled a little.

“Thank you,” I said. “It’s beautiful up here.”

Later, in the car, Ahmad told me, “I think you are becoming a little bit Arab.” He said so gently, but this is not a compliment in Persia. On some level, I agreed with him—I was so submerged in Cairo, so cut off from America, that something was bound to change. Yet I still felt like myself. I was disturbed because I had been told I should be disturbed; that the Arab way of doing things, being opposed to the American way of doing things, represented the betrayal of an American self. But I had discovered that I was not my habits. I was not the way I dressed or the things I did and didn’t say. If I were all these things, then standing on that rock and looking west, I should have been someone else.

But I remained.

When the term “clash of civilizations” was coined, it was a myth; the interdependence of world cultures lay on the surface, supported by trade and the travel of ideas, the borrowing of words from language to language. But like so many ugly ideas, the clash becomes a little more real every time someone says the word. Today, it is a theory supported not only in the West, where it was invented, but also in the Muslim world, where plenty of people see Islam as irrevocably in conflict with western values. When threatened, both Muslims and westerners tend to toe their respective party lines, defending monolithic ideals that only exist as tools of opposition, ideals that crumble as soon as the opposing party has turned its back. The truth emerges. It is not through politics that we will be delivered from this conflict. It is not through pundits and analysts and experts. The war between Islam and the West is a human conflict, in which human experience is the only reliable guide. We are all standing on the mountaintop, and we must learn to look out at the world not through the medium of self-appointed authorities, but with our own eyes.