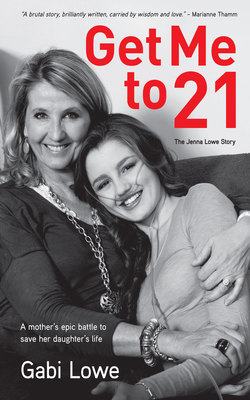

Читать книгу Get me to 21 - Gabi Lowe - Страница 23

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The slow road to diagnosis

ОглавлениеOn Wednesday, the 11th of January we drove home, uneasy and apprehensive, to Cape Town. The next morning Kristi and I bustled about sorting through school uniforms and getting her ready for the term. Jen and I had an appointment at the asthma clinic later that morning. We walked up the clinic stairs, slowly, and pushed open the doors. Jen flopped onto a chair in reception, gasping for air, clearly struggling. She also had chest pain. Her lung function test, though, showed up as normal. How could that be? The doctor was perplexed.

“This is not asthma,” she said. “There is no way this can be asthma. You need a physician.”

“We were at the physician nine months ago,” I said. “We saw Dr VC. We have already been.”

“I think you need to go back, Gabi. It’s good that Dr VC already has all Jenna’s baseline tests. It’s advisable to go back.” She phoned Kathy, our GP, and requested that she get us an appointment with the physician. “It is urgent,” I heard her say.

We secured an appointment with Dr VC for 11 am on Monday morning, so it would be a weekend of apprehension. When I look at Jen’s journal, she was more worried about her school work than her health.

Jenna’s Journal

Saturday, 14th January 2012

School on Wednesday! I need to revise my maths and read my AP books.

On Sunday night I barely slept. I tried to stay calm, to convince myself that everything would be OK, but I didn’t have a good feeling.

Dr VC’s forehead puckered with concern. He asked Jenna to describe what she was feeling.

“It feels like someone is sitting on my chest and I just can’t get enough air in,” Jen explained. “It can really hurt. Not a ‘burny’ sore, more like a deep ache from inside. And sometimes there are sharp pains. I can’t run, or walk fast, or far, without getting completely out of breath. Sometimes I’m out of breath just standing still.”

Dr VC then asked Jen a lot of questions, beginning with “How are you when you wake up in the morning?” and persisting until he had a full and detailed history of the last nine months. Then he sent us downstairs for more chest X-rays and full bloods. He did a thorough physical examination and another ECG in his rooms. Jen described her extreme fatigue and the different kinds of fatigue, the light-headedness and severity of her breathlessness. Listening to it all in one sitting was hectic for me, but Jen was so matter-of-fact about it. These hideous symptoms had quietly and insidiously just become part of her life.

Jenna was presenting with the same problem we had been having for a year now, but still Dr VC could find nothing definitive. We had been in his rooms now for nearly two hours.

“Please just walk down the passage with Jenna,” I said to him. “That’s all you need to do. Just walk down the passage with her and you’ll see.”

Dr VC was an older man, with decades of experience, a mature face, and a kind, no-nonsense sort of manner. “C’mon then, Jen,” he said, “let’s go for a little stroll.”

They were back within moments. Jen was panting. Dr VC picked up the phone and made a call. “Yes, please, Sister,” he said. “An oximeter. Will you send someone up with it?”

The small blue and white oximeter was duly brought up from the hospital ward below his office. Dr VC placed it onto Jenna’s thumb and checked her oxygen (O2) saturation levels. Then they walked down the passage again, stopping every couple of paces so that he could check the levels. Dr VC didn’t look happy. “Jenna’s oxygen levels are dropping as she walks,” he said. I could hear from his voice this was significant, but I didn’t understand why. I would later find out that whether one walks up a hill, runs a marathon or takes part in the Olympics, one’s oxygen saturation levels (the levels of O2 present in your blood) will remain stable. Even when we get out of breath, our oxygen saturation levels will remain relatively the same. This was not the case with Jenna. It was not a good sign. It was serious.

Dr VC spoke gently but firmly and carefully. “So,” he said, “that test that we didn’t think was necessary last year? I am going to send you to do it now. It’s a sophisticated and expensive assessment, but the indication is that we should go ahead. In fact, we are definitely going ahead.”

“Now?” said Jen. “I have things to do before school tomorrow.”

“Yes, now,” he replied.

He picked up the phone again and called his colleague. “Right,” he said, turning towards us. “He will be ready for you in half an hour. It is just around the corner. I suggest you get something to eat and then go straight there. He will tell you what to do when he has the results. Okay, Jen?”

“Yes, Dr VC,” Jen said. Jen was no rebel, she would do exactly what the doctor suggested. So would I.

We chatted cheerfully in the car, relieved that at least something was being done to finally get to the bottom of this. “I can’t wait to see everyone at school, Mom, and hear everyone’s exchange stories. I’ve missed them all so much! Also, I want to do some past papers tomorrow, it’s been a whole term of no maths, and I’m a bit worried about that.”

“You’ll be fine, Jen,” I said, “I know you will. Rather rest and get completely ready for the term. There will be lots of time to catch up.”

We sat and shared a cheese and ham sandwich in reception while we waited, Jen scrolling through her phone.

“Jenna Lowe?” the technician called out.

“Here,” she said, smiling, putting her phone away instantly.

“Right, so I am going to have to give you a little injection before we can do the test,” he said. Jen was a co-operative patient.

“No problem,” she said, smiling brightly.

I was asked to wait in reception. I phoned Stuart. “She’s gone inside,” I said. “I’ll keep you updated.”

Fifteen minutes later Jen joined me. I looked at her quizzically. “And?”

“It was no big deal,” she said. We sat quietly together and waited for the results. Half an hour went past. I was not comfortable.

“Mrs Lowe? Are you Mrs Lowe?” The tone of the technician’s voice was far too caring. And he was looking straight at me, no longer making eye contact with Jen. “Um, here are the test results,” he said, adjusting his glasses as he handed me a large brown envelope. “I need you both to go straight back to Dr VC. I just spoke with him – he is expecting you.”

“What’s going on?” I said. “What did you find?”

He looked at Jen and then back at me. “Her ventilation perfusion is not normal,” he said.

“What does that mean?” I asked, confused.

“It looks as though there are clots in her lungs,” he said deadpan. He didn’t move. Neither did I. A weird feeling crawled up my spine.

“Clots?” I said carefully. “I don’t know what that means?”

“I’m sure the doctor will explain everything,” he said.

I took the envelope, took Jen’s hand and we walked to the car. Subdued, we drove back to Dr VC’s rooms. Inside, my mind was racing. Clots?! Why would a young girl have clots? What did this mean?

“So, Jen,” Dr VC said, looking at her directly, “your VQ scan shows multiple areas of ventilation perfusion mismatch indicative of multiple pulmonary emboli – blood clots – which would explain why you are finding it hard to breathe.” He took a deep breath and then said, “I need to hospitalise you for more tests and monitor you. You will go onto blood thinners immediately and then we will take it from there, okay?”

Hospital? Blood thinners? I thought only older people took blood thinners. Questions were racing through my head, but I forced myself to stay calm. I reached over and took Jen’s hand. She squeezed mine and then looked at him.

“Thank you, Dr VC,” she said, “but please can I go in on Saturday? I start school on Wednesday, and I really don’t want to miss any. Can we do the tests on Saturday?”

He talked slowly and deliberately. “No, Jenna, I’m sorry, there will be no delay. You and Mom are going to go straight back home, collect some pyjamas, a toothbrush and a few things, and I will meet you at the hospital in 20 minutes, okay?”

“Okay,” I said, taking over and gathering Jenna up. “Come, my love, let’s get you sorted.”

We drove home, stunned, and called Stu on the way. Within half an hour we were all at the hospital.

Kristi was calm and contained, chatting lightly to Jen and laying out her stuff for her while Jen lay tentatively under the crisp white hospital sheets. She set out Jen’s toiletries, moved a few chairs around and improved the room, and plugged in Jen’s cellphone charger and laptop. She kept Jen company while Stu and I met with Dr VC at a small table in the passage. I remember every mark on the wall, the uncomfortable chair, the body language and looks on the faces of visiting families. The foot rug was skew. Our meeting would be a long one so Stu phoned Ali. She came to sit with Jen and then take Kristi for supper. She did that a few times that week. Stuart and I were in shock. On auto-pilot. Dr VC was concerned. That was clear.

It was hard to leave Jen at the hospital that night. I wanted to stay. She looked so little in that blue gown. Stuart and I barely slept. I played the last three weeks over and over again in my mind. Images of the VQ scan haunted me. This was clearly something Dr VC had not seen before. He explained there could be many causes for the emboli, but for now all we knew was that Jenna was in trouble and she had to be monitored closely.

There were many more tests to come, but that night she started oral blood thinners. Warfarin, an anticoagulant, was originally intended as rat poison when, in 1983, scientists unexpectedly discovered its magical ability to thin the blood. How peculiar. As soon as we’d settled her into the ward the pathology lab technician took bloods.

“We are checking your INR,” she explained.

“What’s that?” asked Jen.

“It stands for Internationally Normalised Ratio, and is a measurement of how long it takes for your blood to coagulate. Mostly one’s INR level is at around 1.1. But the doctor wants yours at around 2.2, so we need to monitor you regularly. You will see me again tomorrow. Okay, Jenna?”

“Okay.” Jen smiled at her. She didn’t flinch as the needle went in. She wanted to make this poor woman’s job easier. It was the first of many ongoing blood tests.

Turns out it’s quite a thing to keep your INR levels stable. If your INR becomes too high, it greatly increases your risk of internal bleeding. And, in Jenna’s case, if her levels were too low, it greatly increased her risk of clotting and creating more thromboembolisms. What you eat, drink or digest in any way (such as medication, painkillers or supplements) will interfere with your levels. As a blood thinner Warfarin is highly effective, but it has to be managed carefully with consistent diet and blood tests.

“How long will she be on this?” I asked Dr VC.

“I’m hopeful that once we have thinned her blood sufficiently, the clots may start to dissipate,” he said encouragingly. How long would that take, I wondered. A few days, a week, a month? And what did he mean “may”? “For now, I encourage you both to go home so Jen can get some rest. We will talk again tomorrow – I have arranged further testing.”

My eyes snapped open at 5 am. Jen was in the hospital. It was the first day of school – and for those, like Kristi, starting high school at Herschel, it was Orientation Day. What should have been an exciting first day for Kristi now had a different taste to it. She wanted to go via the hospital so that she could say good morning to Jen, so I hurriedly made her lunch-box and we set off. Jen was so loving. She wished Kristi luck and waved her off encouragingly.

As Kristi headed into her first day of high school, I made my way to the headmaster’s office. The office was bustling but he made a plan to see me. He was shocked by Jenna’s news. “Gabi, please stay in touch,” he said. “I will tell Jenna’s teachers and keep an eye out for Kristi. If there is anything you need, absolutely anything, please let me know.”

By day three in hospital Jen was still just as breathless. She was sent for another chest X-ray. I was standing in her hospital room waiting, looking out the window in a daze, when she was wheeled back in by the nurse. She smiled up at me radiantly. It hit me in the chest like a mule kick. My child was in hospital and in a wheelchair, and no one really appeared to know what was going on. I wanted to cry. “Hello, my darling. How was that?” I said instead.

The doctors were more befuddled; it was a confusing medical picture. “I’m thinking of calling in a specialist professor and pulmonologist from UCT Academic Hospital,” Dr VC said to Stuart and me in the passage outside Jen’s room. “He may be the right man to help us towards a diagnosis.”

“Let’s do it,” Stu said. “Why wait?”

Prof. Wilcox from the UCT Academic Hospital was about to become a regular fixture in our lives.

Word got out about Jen fast. Friends began visiting and the phone started ringing off the hook. We didn’t know what to tell people. Kristi took homework to the hospital at night and then Granny Annie or Ali would take her for a meal. Stuart and I stayed with Jen until lights out.

On day four or five, having examined all Jenna’s test results, Prof. Wilcox arrived. He saw Dr VC for a thorough debrief before seeing Jenna. That day was the first time I ever heard the words “pulmonary hypertension”. In my ignorance I believed it sounded better than thromboembolisms.

Prof. Wilcox was a smallish man with light green eyes, glasses, greying hair and scruffy eyebrows – if you were to cast a professor in a movie, he would be awarded the role. He spoke in a quiet and considered manner.

After a long while examining Jen, Prof. Wilcox looked at us intently. “I can’t be sure, but I think this could be pulmonary hypertension,” he said. I was trying so hard to listen, to take it all in, but the words were slippery and foreign. “Or,” he continued, “maybe pulmonary hypertension with an element of chronic thromboembolic disease.” What language was he speaking, I wondered, as he turned his attention to Jen. “We will carry on with your blood thinners, Jenna, but I want to keep your INR at around at least 3 just to be safe. I might also put you on something called Sildenafil, but we will explain that later. Meanwhile, I’m going to move you across to the UCT Academic Hospital for further tests. Is that okay?”

Another hospital? I thought we were about to take her home.

Prof. Wilcox ordered an ambulance the next morning to do the transfer. Wow. It was hard to absorb. “I will see you there tomorrow. But Jenna,” he said in parting, “don’t Google. We don’t know for sure what we are dealing with and there is a lot of misinformation on the internet. Pulmonary hypertension is a complex condition.”

Jen was given a ward on her own in UCT Academic Hospital with the nurses’ station right outside her door. Because of that we were able to be at her side most of the time. Prof. Wilcox had thoughtfully arranged it that way. Friends and family took turns to visit. And delicious meals miraculously arrived at the ward thanks to Andrea, a generous friend and renowned caterer. It was a real gift – there was no time for cooking. I spent barely a minute at home.

Prof. Wilcox did another whole battery of tests, the same and more. Included was a much more targeted echo-cardiogram conducted by a specialist technician who knew exactly what she was looking for. He also did the dreaded “six-minute walk test” with Jen. Her first of many. This is a standard assessment tool for PH patients to clock their exercise tolerance, desaturation and chest pain when walking. Jenna came to dread this test over the years. The hospital’s specialist cardiologist and haematologist also got involved. Jenna’s case was quite a novelty for these academic doctors, but they handled her, and us, with care.

When visitors came Jen would “hold court” from her bed, gracious and dignified, and somehow managing to rock that hospital gown. She often had us in stitches with her dark humour. She was hungry for news of the outside world and for friends. There was no mention of her chest pains, injections, blood tests or nasty side-effects. And no mention of her fear. That she kept to herself. In the hours between visitors and tests she slept while Stu or I sat by her side. In the evenings Kristi balanced her books on the bed to do homework and we sat around chatting as if this was our regular dining room table. I got so used to driving to the hospital that, one day, I drove right to the doorstep of the hospital before realising I was meant to be somewhere else entirely. Some nights, when we got home late, there would be a meal and a note from my friend Mary. If there had been no cars in our driveway all day, she knew we would arrive home hungry and weary. Her thoughtfulness went way beyond the norm.

The echo-cardiogram, among other things, showed that Jenna’s pulmonary pressures were up.

“It’s possible,” Prof. Wilcox said, “that Jenna does have pulmonary hypertension. There is a test, a catheterised angiogram, which is considered the gold standard test for PH, but we will not do that right now.”

“Why not?” I asked.

“It’s a more invasive test,” he said. He wanted to wait for Jen to stabilise before ordering it.

So, for now the diagnosis, as we understood it, was that Jen had chronic pulmonary emboli. There was hope that they would be contained and dissipated with the regular treatment of blood thinners. She was still breathless and fatigued, and had chest pain, but it was far less severe. It was time to take her home. We were delighted.

“But, Jen,” said Prof., “you have to take it easy. Absolutely no exercise. And regular blood tests. You need to be consistent with your medication and have lots of rest. You will come to me for an appointment next week.” He knew he could rely on her to be compliant. We packed up Jen’s things fast and took her home before he changed his mind.

Jenna stayed in bed for a while, and we monitored her symptoms carefully. She was coughing a lot and complaining of what she said felt like pulled intercostal muscles, at the back of her lungs. We seemed to be managing it until after a few days she coughed up blood. We went straight back to Prof. He was concerned that despite her INR levels being between 2.4 and 3.2 this may be another embolic episode. It was decided to keep her INR levels even higher. Around 4, if we could. He further increased the dose of Warfarin and monitored her INR very carefully with blood tests. The coughing started to settle down.

Jen could not wait to get back to school. She was concerned about the amount of work she was missing and really wanted to see her friends. She started with half-days, taking work home in the afternoons. Kristi was so happy to have Jen on campus; at last they were together, albeit in much different circumstances than expected. They spent breaktimes chilling under the trees with Jen’s mates.

I was on top of the medical regime, at times deeply worried and at others optimistically hopeful that this would pass. Even though her diagnosis was not yet finalised, Prof. Wilcox had spoken often enough of suspected pulmonary hypertension for me to know it was time to get to grips with what PH was and do some in-depth research. I started Googling and reading through medical journals. PH sounds pretty innocuous, right? Well, it’s not. In fact, what I came face to face with was pretty horrifying.

Pulmonary hypertension is a complex and commonly misunderstood disease.

A rare and life-threatening lung disease, pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is when the small veins and arteries of the lungs become damaged and constrict, making it very difficult for a patient to oxygenate their body.

A quick biology lesson in case you have forgotten:

“The heart and lungs work together to carry oxygen throughout the body. The heart is a muscle made up of two halves that pumps the blood. As deoxygenated blood returns from the rest of the body, it first goes into the right side of the heart, which pumps it into the lungs. The lungs take carbon dioxide from the blood – which the body releases as you exhale – and replace it with oxygen that you have inhaled. After the blood picks up the oxygen, it is considered ‘oxygenated’ again and is ready to go to other areas of the body. The blood then travels from the lungs into the left side of the heart. The left side of the heart then pumps the blood to the rest of the body. This process starts over again with each heart beat.”1

I scoured through the material, sharing it with Stuart. The information was always carefully worded – “It is complex …” “There are treatments available …” “Each case is unique …” – and densely populated with medical terminology. I was looking for the bottom-line. Some of the words that kept jumping out at me over and over again were the following: “can live for many years with the right treatment”; “medication and multiple treatments can extend life span”; “can improve quality of life”; “there are many different causes”; “average age from 35 onwards”; “many different categories”; “find the right doctor”; and “triple therapy required and early treatment critical”.

Chronic thromboembolic disease was a sub-section or category of pulmonary hypertension, and there were many others. It was so complicated, but everywhere I searched and whatever I read contained the real kickers, the phrases that, as a mother, you never ever want to read: “average prognosis from diagnosis to death 3–5 years …”; “survival can be increased with the possibility of a double lung transplant …”

I was reeling. We were reeling. There must be a mistake. Did Prof. Wilcox really think Jenna could have this awful life-threatening disease? Stuart phoned him. We needed to talk. It was time to ask the hard questions.

Prof. Wilcox saw us on a Saturday morning. I had printed out all the medical articles and we had a list of questions ready. There were no absolute answers, Prof. said, but yes, it was highly likely that Jen had pulmonary hypertension. She had no evidence of an underlying condition so understanding the cause was difficult. At this point it was what one would call “idiopathic” or “primary” pulmonary hypertension. Even though we pushed him, he wouldn’t give an absolute prognosis. He was careful to manage our fear and horror. What was clear to us was that this was not going to be an easy road.

Stuart was the first to ask about a lung transplant. I found the concept brutal. But yes, Prof. said, the chances were that Jen would need a double lung transplant at some stage in the future. If a double lung transplant was a solution, Stu persisted, why didn’t we just do it now? Because, Prof. explained, lung transplants are extremely difficult surgeries and they don’t buy you a lifetime. We would have to wait until it was absolutely necessary. I wanted to vomit.

Stuart and I stood for a long time in the carpark after that meeting, weeping. We couldn’t go home and face our girls like that. We had to pull ourselves together.

Jenna models for Cosmopolitan SA magazine

Kristi (2) and Jenna (5) with dad Stuart

Jen with her godmother, Sandy

Jen (7) doing yoga on the beach

The Magic Bissie Tree by Jenna Lowe

Jenna the bookworm

Sweet 16 – Jen with surfer boy Nic in Plett

The Lowe family with their faithful hounds, Sahara and Prince

Jenna Lowe, deputy head girl, 2013

Jen and Kristi – as close as two sisters can be

Herschel Valedictory Day with Granny and Grampa

Cousins Natalie and Jen – oxygen buddies

Shooting the #GetMeTo21 campaign from Jen’s bed

Jen on her way to the prefects’ dance

Alex – friend and Jen’s matric dance partner

Jen and Daffy

Kristi and the love of her life … Riaan!

Jenna and Camilla

Kristi sings ‘I Need More Time’ at Newlands rugby stadium before the Stormers match and (bottom left) Jen thanks the crowd for their support

Jen thanks the crowd for their support

Gabi mixing Flolan in her cabin on Reach For A Dream cruise