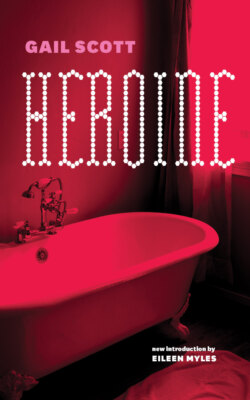

Читать книгу Heroine - Gail Scott - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Dream Layer

Оглавление’Tis October. On the radio they’re saying ten years ago this month Québécois terrorists kidnapped the British Trade Commissioner. I was at my kitchen table. Through my window the mellow smell of autumn leaves in the alley. Making me slightly ill due to a temporary pregnancy. A drunk wove along the gravel. I was just wondering how to put it in a novel when the CBC announcer said: ‘We interrupt this program to say the FLQ has kidnapped Britain’s trade representative to Canada.’ I couldn’t help smiling. Even a WASP, if politicized, can recognize a colonizer. Besides, the crisp autumn air always made me restless. Later, my love, we laughed so hard when the tourist agent told the group from Toronto looking for cultural manifestations in Montréal: ‘Eh bien ici les manifestations ont lieu d’habitude au mois d’octobre.’ Winking at us in line behind them (we were going to Morocco). For in French manifestation also means political demonstration. He meant the October Crisis and other assorted autumn riots. People were freer then.

Alors pourquoi Marie a-t-elle dit que je ne serai pas au rendezvous? She meant on the barricades of the national struggle. Her face had this funny look, half guilty, half cruel. (She was still in the revolutionary organization then.) Even hinting that my grandfather might be Métis didn’t convince her. Of course I didn’t tell her and the other comrades the family kept it hidden. Why should I? They must have guessed anyway, because M, one of the leaders, tugged his beard and said: ‘We’re materialists. We believe one is a social product, marked by the conditions he grew up in. You’re English regardless of your blood.’ We were sitting in the revolutionary local. Around the table no one said a word. Even you, my love, I guess you wanted to keep out of it.

Marie’s face had that funny look again today when she came to visit. She was wearing an immaculate silk scarf. Over it her nose turned aside as if offended when she saw the state of my little bed-sitter. Granted, it’s kind of tacky. Green patterned linoleum and an old sofa. In the bathroom, black-and-white tiles like they have in the Colonial Steam Baths. Except some are falling off. Trying to make light of it, I said as we stepped into the room: ‘Ha ha, the hard knocks of realism.’ She didn’t laugh. She didn’t even smile ironically. So I decided to hold back. Refusing to explain how I’m using this place for an experiment of living in the present. Existing on the minimum, the better to savour every minute. For the sake of art. Soon I’ll write a novel. But first I have to figure out Janis’s saying There’s no tomorrow, it’s all the same goddamned day. It reminds me of those two guys I once overheard in a bar-salon: ‘Hey,’ said one, except in French. ‘Did you know the mayor’s dead?’ His lip twitched. ‘No kidding,’ said the other. ‘When?’ ‘Tomorrow, I think.’ They both laughed. Sure enough the next day on the radio they said the mayor was at death’s door. Nobody knew why. City Hall was mum. Rumour had it there’d been an assassination attempt by some unnamed assailant. I felt like I’d seen a ghost.

I got that same feeling again later taking a taxi along Esplanade-sur-le-parc. On my knee was the black book. The budding trees were whispering, the birds were singing: a beautiful spring eve. (Like when we first fell in love, my love.) When suddenly on the sidewalk I see a projection of my worst dreams. A real hologram. You and the green-eyed girl. Right away I notice she’s traded in her revolutionary jeans for a long flowing skirt. And her hair is streaked. Very feminine. As for you, you’re walking sideways, the better to drink her in. With your eyes. Oh God, obviously you can’t get enough. The taxi dropped me at the bar with the little cupid holding grapes in front of the mirror where I was going to meet some gay writers. One of them said: ‘Chérie, you look terrible.’ I was speechless. All I could think was what a coincidence. Because at the moment I saw you, my love, I’d been writing in the black book (not believing yet that our reconciliation was really finished): He’s Mr. Sweet these days. I’m the one who’s fucking up, making scenes. Oh well, tomorrow’s another day.

‘Qu’as-tu?’ asked Alain. He has green eyes like my father, but he wears jewellery.

I said: ‘I think I’ve seen a ghost. Real-life from a nightmare I once had. Everything back exactly as it was.’

‘Trésor,’ dit-il, ‘la science dit que la répétition n’existe pas. Les choses changent imperceptiblement de fois en fois. Maintenant tu vas prendre un bon verre.’ I didn’t reply, concentrating as I was on how to be a modern woman living in the present while at the same time finding out who lied, my love, me or you?

A delicious warm sweat is forming on the bathroom tiles. Through the open door I see the dented sofa where Marie sat this afternoon. Determined as ever with her flat stomach and her straight back. In that immaculate white silk. Suddenly she put her hand over her mouth, as titillated as a little girl who’s caught a glimpse of something unspeakable. I knew it was that place above the stove where the dirt adheres to the grease, working the paint loose until it starts to peel off. And she was about to criticize my housecleaning. To ward it off I focused on how growing up over that dépanneur in St-Henri probably made her fussy. Every Monday and Thursday after school she had to take off her blue tunic and scrub and scrub the slanting floor under the domed roof. What got her was the darkness of the courtyard. You could feel it from the kitchen window. One day, walking in there she found a big rat lounging on the table. Slowly unwinding his virile tail, he looked at the little girl with his small eyes and said: ‘Mademoiselle, voulez-vous me ficher la paix?’ In International French. She couldn’t think of a thing to say. None of the neighbours spoke like that. Later, she thought it was a dream.

Glancing only slightly in my direction, she blurted it out in spite of herself: ‘Tu pourrais faire un peu de ménage. On dirait que tu n’as plus d’amour-propre.’

I kept silent. It’s better than saying: ‘What about you? You’re too obsessed with how things look.’ Besides, as I’d decided to take a bath, I was busy with my ablutions.

I guess I lost track of time. Because I didn’t see her get up and say goodbye. I realized she hadn’t said anything about coming back.

Colder times are coming. In the telescope the plain whitens. The tourist sees a field of car wrecks below the skyscrapers. A woman is walking toward a park bench. Suddenly she sits, pulling her coat down in the front and up in the back in a single gesture so you can hardly tell she’s taking a pee.

Oh, faucet, your warm stream is linked to my smiling face. Outside the shops swing: peanuts, blintzes, Persian rugs. Marie m’a dit: ‘Tu as payé avec ton corps.’ Shhh. Reminiscences are dangerous. Who said that? Never mind. When I get out of here I’m going to throw out those old pictures on the stool by the tub. That one half-hidden in the folds of the second-hand lime-green satin nightgown must have been taken in Ingmar’s courtyard. Black and white with a silvery grey light shining on the shoulders of our dark leather jackets. We were the perfect revolutionary couple, tough yet happy. Leaning together after a walk in the Baltic fog, eating almond-cream buns. Except at Ingmar’s somebody almost stole the silver plate from me.

What went wrong wasn’t obvious. Earlier, travelling in Morocco, everything seemed perfect. The magic was in slipping out of time. No landlords, no waiting for you to phone, my love. The air was filled with spice, roast lamb, mysterious music, the delicate odour of pigeon pie. From our hotel room we heard an Arab kid with a knife offer to make a rich woman tourist high for a price. We laughed as his voice mocked her under the arch of the starry sky (’twas in life before feminism). I loved our mornings. Honey and the smell of Turkish coffee in the huge café at Poco Socco. With the passing donkeys and men in felt hats and beautiful djellabas obscuring our view of the rich American junkies on the other side, I wrote a poem:

the music of your tongue

slides between my lips

the tongue of your sandal

between my toes

glides through the grass in the orange grove

there has been a communist purge

a dead scorpion lies upturned

on the road to the fortress

Then we were heading northeast across the desert. After a day and a half, the train rolled into flowered vineyards, then the city of Algiers. In a lighted square, a white-clothed man with a thin dog leaned back, playing his flute to lions of stone. Stepping off the train, a plainclothes cop arrested us. It was midnight. He led us out under the Arabian arches of the station. Saying it was for our own protection. Because the streets at night are dangerous. ‘God,’ I thought, ‘somehow they’re on to the fact we’re into heavy politics back in Montréal. What if they find the poem with the word ‘communist’ in my purse? Now I’ve really blown it.’

The police station was plastered with pictures of missing children. Beautiful girls and boys of all ages. Probably sold to prostitution. That’s racist. They let us spread our sleeping bags in the same cell. When in the morning they said: ‘You can go now,’ my love, I was so relieved it seemed that anything was possible. So at a fish supper in a fort restaurant on the middle corniche where Algerian freedom fighters had daringly resisted the French, I said: ‘You’re right to be against monogamy. As long as we trust each other anything’s okay.’ Through the open window I saw a beautiful brown man, naked from the chest up. He was looking in, holding a fish net. As if he’d emerged from the sea. ‘Anyway,’ I added, ‘the couple is death for women.’ You smiled with your wonderful soft lips. We headed north. In the mirror of a hotel room in Hamburg, you took a self-portrait.

Everything was perfect.

Except, at Ingmar’s, your mother’s boyfriend’s winter house on the Baltic, something started going wrong. That particular morning, I must have been dreaming. Because lying back I saw a face looking through a window, smiling. Vines around its neck. Glistening as though it had risen from the sea. Only, outside a slow brown river ran. It was the city. Pink lights on tall white buildings. Red and yellow streets. I woke up to a winter morning. Shadows of noir et blanc. Smell of coffee in a china cup. Bluish tile cooker reaching to the ceiling, Northern European style. Yes, everything was perfect. So why at that precise moment did I get up, open the cooker’s little brass door, and throw the photos of your former lovers in the fire? Just as you came in.

Your silence left me confused. All that European retinue across the winter room. Then the Modigliani print on the wall behind the golden strands of your hair reminded me I needed a man like you to learn of politics and culture. I’d have to try harder. Thank God, despite my error, our days continued to be wonderful. Walking white streets eating almond-cream buns. The falling snow giving an air of harmony. Yet under that blanket of perfection (we were a beautiful couple, everybody said so) the warmth seemed threatened. As if I couldn’t handle the happiness. Secretly the darkness of the closet beckoned. I wanted to sink down among the silence of your coats. (Good wool lasts forever.) Your mother, turning her head from a conversation with her son, said to me: ‘À quoi ressemble ta famille?’ I saw the smokestacks of Sudbury. And her emaciated face sitting on the veranda. ‘Fine,’ I answered, smiling broadly as if I didn’t understand the question.

The feminist nemesis was that the more I felt your love the harder it was to breathe. In Hamburg, when the subway stopped between two stations and the lights went out, I began to sweat. Pins and needles pricked my chest so much I wanted to grab your sleeve and say: ‘Help, please.’ But hysteria is not suitable in a revolutionary woman. Thank God a winter-shocked unemployed Syrian immigrant started to bark. His family gathered round him laughing nervously. Eyeing back the fishy stares of other passengers as if it were a joke. As if it were a joke. My fear of crowds at demonstrations was harder to conceal. Although you’d have been initially forgiving. Because paranoia in new politicos is normal. Given how scary it is to become conscious of the way the system really works. Anyway, following that little blow-up at Gdansk, when we went to a local march in solidarity, I heard the press of soldiers’ feet behind us. Someone yelled: ‘To the church, to the church!’ My love, the crowd was barreling down so heavily that when they closed the huge oak door I was out and you were in. How could you have let it happen? How?

It wasn’t the right question.

The peace in a foreign place was visiting your grandmother. Behind the winter-spring light she stood in her embroidered apron. I said: ‘Hers is the last generation before occidental cultural homogenization, dominated by America.’ You looked up, interested. Just then your cousin came into the room. Behind her glasses I detected an infinite sadness. ‘Gertrude’s dead,’ she said. ‘We think she killed herself because of Lenz. He was having an affair.’

I quickly checked the woman in the mirror over the mantel. She had straight bangs and a well-cut raincoat. It couldn’t happen to her. Although I’d have to play it careful now, given how weird I felt. The trick was to sit straight in my chair (like a European woman), carefully modulating my voice when we disagreed so as not to sound aggressive. You hated a lack of harmony. Unfortunately, my old self-conscious laugh came creeping back. Especially after your high-school girlfriend came for a visit. Watching the two of you dance over the Marienbad squares, with her head in that safe place under your chin, I felt like screaming.

Suddenly you grew cooler. Wound up as I was, I didn’t see at once that I was spoiling things by trying too hard. Not until I read about the German guy they wrote of in the paper. He wanted a driver’s licence more than anything in the world. Due to the fact he’d stayed home on the farm to take care of the folks and needed a way out. Just to make sure he wouldn’t fail, he practised in the backfield for several years. Then he passed the test without a hitch. The tragedy was that driving home down a country road he hit a girl. In the dark and pouring rain she seemed dead, so he buried her in the streambed. Incriminating evidence must stay below the surface. After that he tried harder when he hit another, backing up and having several other goes, before sending her, also, to her final repose in the sand under the little river.

I’ve got to get control. Lying with my legs up I see the whole picture in my head. As infinite as unsullied snow. Then a man walks over it dragging an iron-runnered sled. The hard knocks of realism. The dark arpeggios on the radio blend with the sirens outside. Janis is singing that if you love someone so precious their beauty cannot be had completely. If someone comes I’ll turn it off. So no one can say: ‘You’re stuck in the past. In his photos of Morocco; in his images of love.’

That’s what Marie said once. Her exact words were: ‘Il faut choisir. Car une obsession, c’est l’hésitation au point d’une bifurcation.’ We were sitting in Figaro’s Café, circa 1977, looking at a picture of your other woman. My alabaster cheek against her olive one.

The unfortunate thing is, Janis just happened to come on the air this afternoon when Marie was here. Singing ‘Piece of My Heart’ (Take it! Take it!) Reinforcing the impression I was still living in my own soap opera. With an irritated rattle of her silver Cartier bracelets, Marie reached over and turned it down. Through the partly open bathroom door, I watched to make sure her Grecian profile didn’t look toward me and say: ‘Pour moi ta vie prend les airs d’une tragédie.’

She already said that once. A beautiful summer evening, and I’d just come up the sidewalk in my red flowered skirt. Holding out some sparkling cider and a rose for her. She, standing in the doorway, said, smiling: ‘Tu as les petits yeux pétillants, pétillants, pétillants.’ Then her face darkened and she showed me a scientific astrological analysis of how women with my birth date often end badly. The example was Janis, born on the same day. Dead of an overdose. I said: ‘Yeah, but she died famous.’ Sepia, what scared me was the look in Marie’s eyes. As if she knew something terrible would happen. I could only think, my love, that it was in regards to you. So I added nonchalantly: ‘Anyway, to the victor belongs the spoiler.’

I’m sorry, my love. You were a new man who tried. I just wish you hadn’t always spread yourself so thin. At the time it was hard to argue. For when I said: ‘Charity begins at home,’ you said: ‘That isn’t communist. What interests us is collective life.’ And I could hardly deny the veracity of your statement. The only solution was to find another way to pose the question. Marie said: ‘Nous sommes des femmes de transition. En amour, il nous faut éviter la fusion. Évidemment, this leaves a woman pretty empty. I see no other thing to do but write.’ I knew what she meant. Putting one word ahead of another on the page gives a feeling of moving forward. I started thinking of the novel I would do.

To get in the mood, when I get out of this tub I think I’ll go to that artists’ café. The young men sit there every day in black leather jackets and headbands, watching the leaves blow across the street. The bubbles coming from the coffee machine warm the cockles of a single woman. Have to be careful what to wear. In case I meet you and the green-eyed girl. No. The trick is not to be defeatist. Inside the café the smell of coffee is encouraging. A lesbian sings of love in a telephone booth. Her voice rings above the clatter of dishes. This morning an artist was screaming: ‘Those fuckers didn’t give me a grant.’ He meant the government. He was pounding the table with his left hand. Before smiling to himself and drawing circles on his movie program. Outside, an old woman was rubbing her stomach as if hungry. He flicked his cigarette at her. It stuck on the orange neon sculpture advertising the work of another painter. She threw back her toothless head and laughed.

My little room is so quiet now. You can almost hear the snow falling on the sidewalk. I’ll just turn on the radio. Tonight they’re doing that retrospective of women singers, maybe Bessie, Edith, Janis. All their biographies end badly. That won’t happen to the heroine of my novel. She was pretty sure of that when (at twenty-five) she climbed off the bus from Sudbury. The smoke hung stiff in the cold sky. At Place Ville Marie she found the French women so beautiful with their fur coats and fur hats under which peep their powdered noses. If anybody asked, she’d say she wanted a job, love, money. The necessary accoutrements to be an artist. She immediately rented a bed-sitter. Stepping off the Métro that night and turning a corner, she saw the letters FLQ screaming on an old stone wall. Dripping in fresh white paint. Climbing the stairs to her room she knew she’d come to the right place. She just needed some friends. She started looking in the downtown bars, working east to St-Denis. Then up The Main. It took a couple of years.

My love, those pictures you took of us on the Lower Main marked the start of my new era. In them I look so happy, so free. Even the dilapidated bars in the background have this silver glow. We’re walking from the Lower Main north, your camera clicking all the way. You take one of a guy at the corner of Ste-Catherine pissing in the wind. I remember wondering if it felt good. In front of the Lodeo some Anglo junkies I’d seen hanging around the art galleries wait for a fix. The next shot shows me explaining how artists from rich minorities like les Anglais du Québec need marginal lives in order to feel relevant. My black-gloved hand gesturing in the air. You nod, interested, backing up the street, your eye trained on me through the lens. We enter the Cracow Café. The women have pale faces and dark coats over their shoulders.

I could start the novel here. At the Cracow Café, but a little earlier. Just before we met. I felt something stir in me as soon as I walked in. You were sitting under a Polish poster drinking coffee from a thick cup. Lennon glasses on your pretty nose. From the end of every booth a wooden hand beckoned clients to hang up their coats. You had the sweetest smile I’d ever seen on a man. My first thought was this was exactly what I wanted. You and the others sitting there in wire glasses and smoking hand-rolled cigarettes. Obviously involved in some heavy intellectual discussion. Then the usual moment of doubt when a person naturally draws up a litany of why she’ll never rate. No class. Because in Lively, near Sudbury, a retired mining foreman is something but with an intellectual like you it would be less than nothing. At the time I wasn’t political enough to know of your attraction to the working class.

Anyway, I decided to act confident. Aided by the fact that at that moment the door burst open and some hookers came in. They had snowflakes on their hair and eyebrows. To keep warm one of them was dancing wildly. Left foot over right. Until she saw you had your eye on me. She stopped and stared angrily from under her wide pale brow. Very French. And I noticed she had middle-class skin. Therefore no hooker, just one of your socialist-revolutionary comrades dressed up to help organize the oppressed and exploited women of The Main. ‘Possessiveness reifies desire,’ called a girl with green eyes to her from the next table. So young I hadn’t seen her. ‘Right on,’ I shouted. What did I have to lose? My last lover was a journalist who wouldn’t take off his earphones. And his sheets were full of crumbs. The fake hooker cut her losses quicker than I could have. By lighting a Gauloise and launching into a political analysis of prostitution and the city administration. No doubt the better to get your attention. But I was so busy noting the exquisite beauty of her French brow, wide lips and dimple on the chin that I failed to see, my love, how you were smiling at her as sweetly as you smiled at me.

We get up to go. Or at least I do and you follow. This was an essential moment. Outside in the fog we can hear the gulls calling from the harbour. The cold wind cuts. We start walking. The smell of cappuccino is wafting from some restaurant. I love the smell of coffee.

We’re on rue Notre-Dame. Maybe you’re testing my revolutionary potential for going against the system. Because you say, smiling: ‘Let me teach you how to fish in a junk shop.’ In a display window your hand sweeps away the ropes of pearls. There, on a plaster chest, a purple amethyst. ‘Yours,’ you say, flipping it in my pocket. Outside you pin it on my sweater. My guilty grin is due to the voice of an old woman behind us in the fog. Someone has snatched her purse. ‘Le policier dit que quand il porte son uniforme, les gens arrêtent de faire des mauvais coups …’ she says squeakily to her friend. ‘Mais quand il est en civil …’ We can hardly see her. But we know she’s under some sort of statue. Someone else giggles nervously. The old woman’s voice again:

‘Tu ris comme une bonne soeur.’

The lens sweeps down the stone steps leading from the chalet toward a street opening bulb-like into the mountainside. A grey woman stands up, pushing away her bed of pine boughs. Her hair is silver. Her stockings are stained. Her skirt is a filthy undeterminable colour of suede. She starts walking toward The Main, hugging a fence along a demolition pit. DOWN WITH GENTRIFICATION, says the graffiti. She turns the corner. The narrow street curves gently along a row of red brick flats. In some cases the paint on the doors is peeling off. Those with new cedar windows were recently bought by politically progressive university professors. The grey woman heads toward an empty lot and sits down on a cement block. WAIKIKI TOURIST ROOMS, CHAMBRES AVEC CUISINE, says a blinking sign.

On the bottom floor to the left, I’m lying in the bath. Watching how in the green five o’clock shadow the conflicting patterns on the rug and sofa dim. With the television flickering in the corner beyond the half-open bathroom door. It could be a scene from an old Hitchcock movie. For this is the eighties, but there is a terrible nostalgia in the air. People are buying those fifties lacquered tables with round corners for their kitchens. The couple is also back in the form of the new woman and the new man.

Except us, my love. Because sinking below the line of pain the way I did after we broke up (spring of ’79), then reconciled last winter, it nearly drove me crazy. I wrote in the black book: One night a little tipsy and we’re together again. I love you but there’s no spontaneous outpouring of the warmth I need so much. I drink. I want to take pills and run away. As-tu vraiment peur que je te mange, comme dit Marie? A little later, we had to break up again.

Shhh. Watch the depression. The solution is not to be burdened, as an F-group comrade told me back in ’76. When I got drunk and confessed to him I couldn’t handle it when the girl with the green eyes put one hand on my arm and the other on your bum. As if she were the shock centre through which passed our love. We were in Vancouver. Nature was so beautiful with the hibiscus blooming loudly. I wrote in the black book: Olympic Vacation, July 23. Arrived by train. The end of a long black corridor. Now I know joy is what I’m looking for. Learn to laugh. No matter what the circumstances, being burdened only makes things worse. Don’t be such a Protestant. At the time we were sitting in some wisteria eating a salmon a comrade had lifted from a fish vendor. In the photo I had a nasty frown between my eyes because of trying to explain why it was wrong to steal from the little guys. The comrade answered: ‘Under capitalism, you get it while you can. It’s sure as hell none of them is going to give any of us anything.’ From a transistor on the grass Janis’s voice rose up seconding the motion, singing grab love when it comes along, even if it makes you sad: ‘Get It While You Can.’ Actually, I feel fine as long as no one disturbs my peace. A knock at the door really makes me tense. After all, it could be anything. The welfare lady looking for a reason to stop my cheque. ‘Do you live alone? We hear you have a boyfriend?’ And I’d say just to get to her: ‘Nope, a woman.’ God I hope this place isn’t tapped like the one on Esplanade. With the RCMP listening in on every conversation. Of course it isn’t.

I’m probably just upset due to Marie’s visit. Six months’ absence and she walks in as if it were nothing. Being a woman who never looks back. Maybe that’s what Janis meant by it’s all the same goddamned day. Going with the flow. That Québécoise I overheard in the Artists’ Café had the right attitude. ‘It’s over,’ she told her friend.

‘Oh yeah?’ her friend responded from across the table. ‘Depuis quand?’

‘Depuis un an.’

‘Oh, I hadn’t noticed. No bitterness?’

‘Non, pourquoi?’

My love, I wanted to be that way. The better to save me from embarrassing moments like that time with all we women comrades. A woman’s party, I think. ’Twas near the end of the reconciliation and it was important to be cool. The girl with the green eyes came in looking sad and skinny. With a shock I noticed her hair was cut and with the side part she exactly resembled your mother. That’s how I began to think she was after you. ‘Women get old,’ I told her, ‘so they won’t be attractive to their sons.’

It was a stupid thing to say. But I was trying to control the darkness so I wouldn’t do something ridiculous. In my pocket was the blow-up of that article where Prince Charles, in announcing his engagement, said by way of explanation: ‘Diana will keep me young.’ I was thinking of pinning it on your door. Clandestinely, because when you saw it you wouldn’t find it funny. The idea came as I got up one silver morning, the snow melting so fast a Québec poet had written ‘Time is slush’ and printed it in the paper. You were coming to get the little Chilean girl we were looking after (her parents being illegal in the country). But what to my surprise did I see, as I peeked out the window of the flat on Esplanade, but the girl with the green eyes waiting on the sidewalk. Her smile was surprisingly warm. Still, it couldn’t have been easy. The eyes looked small and swollen as if from crying. And the mouth stretched, almost, in the pale face. I saw the large penis slip between our lips. I felt the soreness of the jaws after a while. This was just before that beautiful April scene where the two of you walked up the street like lovebirds. So when you came up for little Marilù and I asked you how come the girl with the green eyes was also at the bottom of the stairs so early in the morning, you said: ‘We’re all friends, we three, so why are you acting suspiciously?’

I said, the words sticking painfully in my throat: ‘Does friendship include, uh, sex?’

And you said: ‘We’re friends. And you’d know more if you asked less.’

Out the March window I checked her face once more. She looked scared she wouldn’t win. Just like I probably did in that last period of our love. The same face exactly. Except I knew my star was falling and hers was rising. That’s a defeatist way to see the picture. Actually, my love, when you said you were just friends, I believed you. For people were saying she was a dyke. Besides, creeping through a corner of my mind was that funny little slogan: ‘To the victor belongs the spoiler.’ I should have said that to the shrink from McGill who said: ‘We need to find the darkness in you that makes you tolerate such a situation. A woman who loves herself doesn’t put up with a man who deprives her of affection.’

Instead I reminded her for the n th time a political woman has to be open. I repeated once more that the problem with therapy lies in its lack of social analysis. She listened as I pointed out how in coming up the winding oak stairs to her office I’d noticed the panelled walls of the English-speaking school of social work forbade protest with signs that said: ‘NO POSTERING; PAS D’AFFICHAGE.’ They had the same signs except only in French and pinned on the cement block walls at l’Université du Québec. But over there no one paid attention. The place was covered with graffiti. QUÉBÉCOISES DEBOUTTE. SOCIALISME ET INDÉPENDANCE. LE QUÉBEC AUX OUVRIERS. People were freer then.

The shrink, a jolly Aries with a round grey Beatles haircut, asked: ‘Is there any more you want to say before you leave?’

I decided to tell her about the dream. Because there were three birds but I couldn’t see the third bird’s face. Try as I might. It was very frustrating. The first one was a nightingale, very modest, sitting in the long grass in the grey dawn singing a beautiful song representing infinite poetic possibilities for the future. The second was attached to the first by a string. It flew up into the blue sky where the world could see. A painted bird, trendily attractive, chattering madly. But its song was thin. The third was sitting on a tree with its back to us. Fully developed and a beautiful singer. But we couldn’t see what kind it was.

The shrink said: ‘Gail, I think it’s pretty obvious, don’t you? The first one is the darkness, the night in you we talked about earlier. Still, it’s very beautiful when not obfuscated by the image of the second, the painted bird you are choosing to show the world.’

‘Very deep,’ I said sarcastically. ‘Anybody who has been a sympathizer of the surrealist movement can tell you how to read manifest dream content. The point is we have to create new images of ourselves even if at first they’re superficial, in order to move forward. Otherwise we’re sitting back there in the grey dawn. But what’s the latent content? What I want to know is who that third bird is?’

‘Well,’ she said, ‘when you do maybe you will have come full circle. You say the third bird is “fully developed.” I presume that means having transcended the two others. The third bird is your answer.’

I guess dream time is like train time. No line between night and day, yesterday and tomorrow. Waking up periodically on that trip to Vancouver, it could have been a dream. First the large blond woman from Keewatin in the powder-blue pantsuit drinking with the boys all night. Yet staying fresh as a daisy. She’d even left her children home and wasn’t worried. Often when I opened my eyes she’d be telling another joke about Indians or hunting. And once when I awoke a storm was blowing and suddenly out of the forest in a flash of lightning I saw written on a huge stone: ‘With schizophrenia you’re never alone.’ We were going through reserve country.

In the dark I thought how I’d like to capture that loneliness and write it in a novel. But it was already too late because the train was out of the forest and going through a giant field of car wrecks.